A Snowball’s Chance

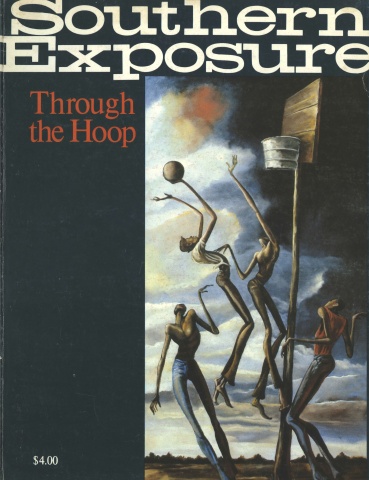

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

For the hopeful and naive soldiers who promised their families a speedy victory and hasty return home, the Civil War proved a sobering nightmare. The bloodshed, on a scale previously unknown to Americans, was terrifying and constant. Only winter camp allowed the armies of the North and the South a desperately needed retreat from the carnage, a chance to rest and re-organize. But each year, commanding officers faced the difficult task of maintaining morale, asserting discipline and promoting physical fitness among their exhausted and homesick men. As a result, “sport of all kinds became the order of the day” during winter camps.

A Virginia officer wrote that the men indulged in “all forms of sports” which served “to break the monotony of confinement.” Enlisted men from each army also reported home that “ball games and other sports . . . were going on all the time” and that on “any pleasant day there was ball playing, running, jumping, wrestling, and scuffling.” Soldiers who learned a taste for early versions of football and baseball during these winter camps t « carried back knowledge of the new sports to their own communities.

Predictably, spectator sports like horse racing and cockfighting had broad appeal. But nothing suited the needs of winter soldiers better than spontaneous mass activities which could be regularized as interest spread. Rabbit chases, for example, became extremely popular and were eventually conducted under established rules. By far the most novel and remarkable winter camp activity, especially for soldiers from the deep South, were huge snowball fights. Snow added to the discomforts of winter, but whenever the snow was right for packing, a battle was inevitable. Contests began spontaneously. A New York soldier recorded such an instance. A group of soldiers “who were the most belligerent" piled out of their tents one morning and for no apparent reason started to shell the company street next to them. Other soldiers retaliated and soon the whole camp was in an uproar.

Once begun, battles spread quickly. A truce might be declared between the original combatants in order to join forces and “shell out” a third party. As more and more recruits entered the contest, organization became necessary. Snowball generals arranged troops into regiments, brigades and occasionally divisions, employed military tactics and led charges and counter-charges. Soldiers took and paroled prisoners, confiscated war booty in the form of pots and pans (and occasionally breakfast). Drums and bugles accompanied by huzzas and rebel yells marked the opening of campaigns. On some occasions, the battles were pre-arranged and soldiers spent sleepless nights devising complicated tactics and amassing piles of ammunition.

Some units took their battle flags into the fight, guarding them zealously since their capture meant dishonor. One beaten Confederate believed that his antagonists intended to record their snowball victory on their battle flag as if it had been a real battle! Some units used improvised battle flags. One set of flags included a red flannel shirt and a pair of grey drawers, each strapped to a pole and carried into the storm of snowballs with unflinching loyalty. On another occasion an unlucky youth returning from furlough had his white shirt stripped from his back by a group of Fort Texas soldiers who hoisted the “oddity” as their battle flag.

This sort of activity frequently got out of hand. In December of 1862, a Tennessee regiment got into a heated contest with another unit. The battle raged back and forth across a small field as charges were disrupted by counter-charges. Arguments developed. Both sides “got so worked up and incensed over it that they got their rifles,” so that they could settle the matter permanently. Part of the army had to be called out to quiet them.

The massive snowball battles of 1862-63 created problems for the Confederate high command. Not only did the battles obliterate military discipline, but soldiers frequently got hurt. After one particularly disruptive battle in early January, 1863, General Longstreet decided that snowball battles would have to stop. General Lee issued a similar order a month later. Both men emphasized, with no success, the dangers of snowballing to life and limb. Soldiers seemed not to be content with merely throwing ordinary snowballs. Frequently, they allowed their ammunition to freeze overnight to increase its destructive force. Other incorrigibles increased hitting power by packing stones and snow together. Beyond this, soldiers, apparently believing that retreat meant dishonor, seldom left the battlefield when ammunition had been exhausted. Instead they stood toe to toe and slugged it out with their fists.

Perhaps the largest single snowball fight in the entire war, if not in all history, occurred less than a month after Lee’s order. It began in Stonewall Jackson’s corps, spread quickly into Longstreet’s camp, and before it ended most of the soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia had participated. The fray started casually enough in the morning, with only a few soldiers involved. But by noon four brigades were at each other’s throats. In the afternoon the cavalry got into the act, and finally a fifth brigade entered the fight. As one observer noted, “Never did any cause inspire its champions with more excitement, zeal, exertion and courage.” One officer described the battlefield as covered with a cloud of snow. So much snow was thrown, in fact, that he wondered how soldiers could distinguish friend from foe.

Finally, just as the sun was setting, the valiant Stonewall Brigade, which had been instrumental in starting all the trouble, succeeded in driving the enemy into their tents. It was estimated that the battle had involved over 24,000 soldiers, spread across an area of 10 square miles. While the scale of this contest appears unprecedented, skirmishes which engaged 6,000 to 10,000 men became almost commonplace.

Union commanders also faced discipline problems. Enthused snowballers refused intervention, as an officer in the 28th New York found out the hard way. He decided that the men were getting “too serious in their play.” In an attempt to quiet the disturbance he mounted a stump and addressed the combatants. He was rewarded for his attempt by a shower of snowballs and was compelled to “beat a hasty retreat.”

When the snow fell, rank had no privileges. Like some other games, snowballing permitted the settling of old scores between officers and their men, and those officers who didn’t accept their share of snow in the face were paid off in less harmless ways. Irvine Walker, a South Carolina officer, although “not fond of such frolics,” found it necessary to join. “The men did not let off anyone in the Brigade” with the exception of the commanding general. This officer noted that “all distinctions were levelled and the higher an officer, the more snowballing he received.” Many popular officers found it impossible not to participate. On December 4, 1862, shortly before the Battle of Fredericksburg, Jeb Stuart and his whole command post were surrounded and captured by his own troops for fun, an accomplishment which the Union Cavalry would have loved to duplicate.

Stuart was, of course, partly responsible for his predicament. The combatants had not originally intended to include Stuart’s headquarters in their list of objectives. Unfortunately, headquarters lay in the direct path of the contending armies. Stuart and his staff, chilled and weary from a recent journey to Port Royal, had at first taken every precaution to ensure the neutrality of their position. In a final symbolic effort they hoisted a white flag. But as the battle raged back and forth near his command post, Stuart’s curiosity was aroused. To get a better view of the struggle, he and a fellow officer mounted a huge supply box.

Merely watching, however, was not enough for the energetic, fun-loving Stuart. He began to shout encouragement and advice to the defenders. Stuart’s exposed position was irresistible. He very quickly became the target of well-directed shots. When the defenses finally collapsed before the weight of Hood’s Texas Brigade, part of the war booty was a wet, but feisty, Jeb Stuart. But he did not remain a captive for long. A countercharge swept back through the camp and he was once again free.

Such snowball battles lifted many sagging spirits. A New York artilleryman recalled a battle at Brandy Station in the winter of 1864. “It certainly did me a service, for I have been so blue lately, and have been so confined, and felt so discouraged, that the effect of a hearty laugh was beneficial.” But more than this, the snowball battle had made him feel young again. “I am beginning to feel very old — older every day.” A member of the 113th New York echoed the sentiments of many when he said, “There were bloody noses and cracked crowns on the occasion; but after the battle there were no gallant fellows lying dead in the snow. . . . It is to be wished that all fights were like it — the bloody and brutal farce of war no more a tragedy than this battle of snowballs.”

Tags

Lawrence W. Fielding

Lawrence W. Fielding teaches in the Department of Physical Education at the University of Louisville. He is a founding member of the North American Society for Sport History and author of a forthcoming book entitled Sport Along the Road to Appomatox. (1979)