“A Slow, Creeping Death”: Tackling the Todd Nuclear Dump

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 3, "The Future is Now: Poisons, Spies, Terrorism in Our Back Yard." Find more from that issue here.

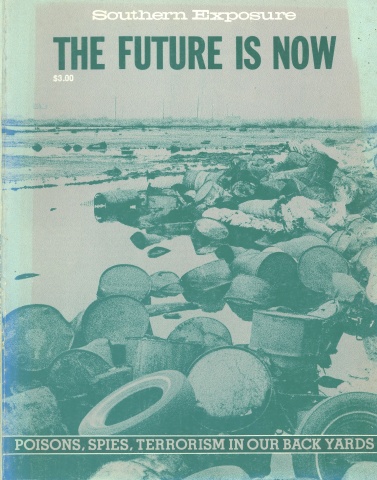

When Hurricane Allen, 1980's much-feared "killer storm," seemed headed for Galveston Island on the upper Texas coast, residents braced for a dose—considered long overdue by most weather watchers-of 200-mile-an-hour winds, high waves, and funnel clouds. Instead Allen blew ashore a couple of hundred miles further south, sparing the port city from a disaster that could have been even greater than the one that wiped out Galveston in 1900. The danger lay on Pelican Island, an island in the Houston-Galveston ship channel that faces Galveston Bay on one side and lies only 2,000 yards across a narrow channel from the densely populated city on the other. Pelican Island was then the home of over 10,000 barrels of radioactive waste, some of it mixed with flammable chemicals. The drums sat out in the open without adequate protection from high tides or hurricane-force winds. Alongside them were 14 22,000-gallon tanks holding over 300,000 gallons of radioactive coolant water from two nuclear power plants. Many of the 55-gallon drums, stacked two-deep on concrete pallets in a fenced yard near a nuclear waste reprocessing plant, were already rusting and corroding from the wet salt air and constant sea winds.

Six months before, the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) had submitted an internal report to the Texas Department of Health (TDH), the agency that had licensed the plant 15 years before. The report said the nuclear waste site — owned and operated by the “research and technical division” of the Todd Shipyard Company — could be “destroyed by tides resulting from a major hurricane.” Even though Galvestonians had not been told of this DPS warning, by the summer of 1980 angry residents were being heard from Austin to Washington on the subject of Todd’s dangers. Public interest had been kindled by a series of events that had begun the previous fall. Now, almost two years later, the waste site is being shut down, Todd is out of the nuclear business and Texas has new laws on the books regulating the disposal of radioactive waste. It’s not an unqualified victory for Todd’s opponents: the laws could be better, and Pelican Island will probably never be adequately cleaned up. But things are better than they were.

In November of 1979 this country's three permanent nuclear waste dumps closed, with no assurance that they would reopen anytime soon. Wire service stories reported, however, that a Texas shipyard was willing to take “wastes which nobody else will touch.” Though the Todd shipyard was licensed only for temporary storage of low-level wastes, it opened its doors to receive 3,000 drums a month and quickly doubled its normal radioactive inventory.

This crisis brought Todd its first public attention when Janice Coggeshall, a Galveston city councilor, saw one of the news stories, a short item that said wastes being turned away at the nuclear dump in Barnwell, South Carolina, were to be trucked to a temporary storage facility in Galveston County. It was the first she’d heard of it.

At about the same time, Peggy Buchorn of Bay City, traveling home from San Antonio one night, found herself behind a tanker truck with a radioactive symbol on its back. Buchorn, an anti-nuke activist who has been fighting the construction of a giant nuclear plant near her home, got into a conversation with the truck’s driver via her CB. She discovered that the truck was carrying radioactive water from the Rancho Seco nuclear plant in California and was headed for Galveston to unload.

The same month, Science magazine reported that the nation’s nuclear medicine facilities were about to shut down when they heard of a little-known processing plant in Galveston whose plant manager said he could take most of the medical waste generated in the country.

Galveston Mayor Gus Manuel said he didn’t know Todd was in the nuclear business “until Mrs. Coggeshall told me.” The mayor worried about hurricanes as well as what he called “a slow creeping death for Galvestonians.” Buchorn had already called Galveston’s state senator, A.R. “Babe” Schwartz.

Reaction was swift. The city council and the county health department both passed resolutions asking the state health department to ban all further shipments to Todd and called for a full investigation. Schwartz, who then chaired the Senate’s Natural Resources Committee, began the first of several hearings almost immediately. Texas Governor Bill Clements toured the site. Clements, an avidly pro-nuclear Republican oilman who isn’t easily shocked by the practices of Texas’s big businesses, called the storage yard’s condition “deplorable” and ordered TDH to stop shipments to Todd from out of state. (Todd had by then admitted that 80 percent of its wastes originated outside Texas.) The health department balked and Clements found himself entangled in the interstate commerce laws. “Shut them down anyway,” he replied. “We’ll look at the law later.” Meanwhile, the governor’s energy advisory council, which had been looking into the question of radioactive waste disposal since midsummer, began a series of hearings on Todd’s dump.

TDH Commissioner Robert Bernstein said Todd was only violating the “spirit of the law” by storing “excessively high amounts of nuclear waste in the hurricane-prone area” and secured an “agreement” from Todd that the company would stop taking waste water from nuclear power plants. But Bernstein did admit there were some “weaknesses” in the law which the legislature ought to correct. He, too, decided to hold hearings in Galveston in March, 1980.

All the hearings, with their attendant media attention, finally revealed to the public just how bad the situation at Todd Shipyards really was.

The shipyard had been on Pelican Island since 1934, when Todd bought out an old Galveston construction company and soon became the largest industry in the area. Today Todd owns six other yards; its corporate headquarters are in New York. In 1960, the Atomic Energy Commission, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s predecessor, licensed Todd to service and refuel an experimental nuclear merchant ship, the N.S. Savannah, and to rebuild its tender ship, the Atomic Servant. Several years later, Todd decommissioned the Savannah, which had turned out to be an economic disaster, and decontaminated and sold the tender.

To recoup some of its investment in nuclear technology, Todd decided in 1968 to open a facility for reprocessing, temporary storage and transfer of “low-level” nuclear wastes. Since Texas is an “agreement state” under the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, the state assumed authority for all nuclear materials licensing in place of the feds. Todd did not have to worry about federal regulation of its proposed facility. It had only to apply to TDH’s radiological division. The amounts Todd intended to handle were small at first, and they were exclusively from Texas. However, the license was so easily amended — 31 times — and oversight was so lax that Todd soon found it could do just about anything it wanted with nuclear materials. The company even secured state permission to dump irradiated waters into Galveston Bay — though federal law specifically denies states the power to authorize such a thing.

To a large degree the lax oversight was unavoidable; there simply wasn’t authority for the government to do much about Todd even if it had wanted to. No environmental permits or studies were required, and nothing on the island — the barrels, tanks or buildings — had to meet any design criteria to withstand hurricanes or floods.

The state laws that did apply were grossly inadequate: no bonding was required nor was anyone assigned responsibility for decommissioning the site, cleaning it up or paying for perpetual care. The state’s power to enforce the law barely existed: the penalty for violators read, “Not less than 50 dollars nor more than 200 dollars .. . upon conviction.” The state’s enforcement agency was understaffed and underfunded and faced an evergrowing number of license requests from radiation users. And councilor Coggeshall found that much of the state monitoring consisted simply of “checking paper records prepared by the company.” One health official said bluntly, “The license was unenforceable so we didn’t enforce it.”

At the time of the Senate hearings, Todd was operating under a permit limiting it to storing no more than 2,000 barrels at a time, none of which was supposed to remain on site longer than one year. But Charles Hathaway, the plant manager, admitted to the senators that his yard actually held over 16,000 barrels of waste; 338,000 gallons of coolant water containing radioactive strontium, cesium, iodine and tritium; and 15,000 gallons of toluene, a highly flammable and unstable chemical which no permanent dump would accept.

Further testimony revealed one questionable practice after another. Many of the barrels had been stored for three years. It had been two years since any waste had left the island. Todd shipments had, two years before, been turned away twice from the permanent disposal site at Beatty, Nevada, because they were leaking radiation. Some barrels had never been checked to verify the amounts or kinds of radiation inside. No studies had been made for heavy metals. No monitoring wells existed on the island. No geological studies had been made, nor had there been any study of soil permeability.

Reporters for Hot Times, an Austin anti-nuclear tabloid, found that TDH had detected radiation exceeding permissible limits outside Todd’s fence and that soil samples just outside the plant contained two to 14 times the permissible levels of radioactive cesium, cobalt and manganese. They also found a May, 1979, inspector’s report that said, “Many of the waste drums have been in the open so long that the bottoms are rusted out. . . . This area drains directly into the bay.. . . There’s no way of knowing what, if any material has drained into the bay undetected. ... I did find one area of the bay contaminated with several isotopes.”

In 1979 Todd dumped over 40,000 gallons of irradiated water into Galveston Bay, yet TDH took only one water sample that year. And it was taken a mile and a half from the site, a technique another TDH inspector called “useless” for detecting excessive radiation in the bay. (In February, 1980, the state Department of Water Resources found “some irregularities” in the bay near Todd’s point of discharge.) The condition of the bay waters prompted Ed Ibert, Galveston County’s environmental officer, to announce, “I won’t even feed my cat oysters from the bay, much less eat them myself.”

Even as the various hearings were bringing out the shoddy practices in Todd’s past — and getting sensational statewide publicity — the company kept operating and accidents kept happening.

In January, 1980, Ibert asked OSHA to inspect Todd’s nuclear division. He cited “lax handling of low-level wastes by the workers,” many of whom were stevedores and worked at Todd part-time with little or no training. He also questioned Todd’s practice of piping drinking water through rubber hoses “running along the ground through puddles and around barrels of radioactive stuff.”

Then in early February, before OSHA could get there, 11 workers were accidentally exposed to a “teacup full” of strontium-90. They didn’t know what they were handling because the vials weren’t labeled, and they were initially misled about what it was they had spilled. By the time the full extent of the accident was discovered, workers had tracked strontium-90 from the bathrooms to the parking lots. “The whole plant was contaminated,” said one worker, and “people were cutting their nails till they bled to make sure they were clean,” reported another. Meanwhile, plant officials, including the company doctor, publicly denied for the first 24 hours that the accident had happened at all. And though the workers were eventually told the truth about the strontium, it was six months before any Galveston health officials were told.

On the day after the accident, Todd Shipyards Corporation, whose nuclear manager had boasted in the Senate hearings only three months before that he could handle “up to one million drums” for storage on Pelican Island, announced that it was “going out of the nuclear business . . . due to the insane and hysterical publicity” that had lately surrounded its operations.

Three days later, Todd removed 32 grams of plutonium from one of its buildings. In a March hearing, Hathaway testified that he did not know why the plutonium had been there, how long it had been there or where it had gone. It turned out to be a leftover from the Savannah, and its existence on site violated the provisions of Todd’s lease.

In May, 1980, a fire broke out in the processing building, destroying a vial crusher with radioactive residues in it and coming “perilously close,” in the words of a TDH staffer, to explosive materials mixed with more radioactive chemicals, before it was contained. The health department reported that “a very small amount of radiation” was released into the air and there had been some contamination of the fire-fighters’ boots and the run-off water.

Then in October, Babe Schwartz obtained a TDH document reporting that a shipment including two leaking boxes of plutonium had been turned back from the newly reopened Beatty dump after officials there discovered that the plutonium had contaminated “roughly half’ of the 157 containers it was shipped with. The point of origin: Todd Shipyards. Southwest Nuclear, a California firm licensed to package and ship nuclear waste, had picked up the materials a year before in Albuquerque, transported them to Todd for temporary storage, and removed them a year later at Todd’s request. The material had been stored that year out in the open, at the end of a roadway on the island. It had contaminated the pavement and the nearby soil with not only plutonium-238 and -239 but also strontium-90 and ytterbium-169. Soil samples taken after Todd’s initial cleanup still showed signs of radioactivity. But after two more checks the health department pronounced the site clean. All the soil has been removed.

No one knows how many people came in contact with the leaking materials nor what routes the trucks followed as they criss-crossed several states trying to unload them. One thing is clear, though. No Todd official and no TDH inspector ever checked the containers while they were on the island. In fact, TDH didn’t even know they were there until the leak was reported by Beatty. Todd had never listed the plutonium on any of its manifests.

Todd had finally gone too far. Under public pressure, in January, 1981, the health department sued, and it chose to file under a solid waste act that carried stiffer penalties than the radiation act. Although the state presented a strong case showing continuous violations and clear health and safety hazards, Judge Ed Harris of Galveston refused to grant an injunction mandating immediate action. Calling Todd “a good citizen” that had acted “in good faith,” Harris continued the case for several months, giving the company more time to clean up the site. Todd, worried about the penalties, hurriedly began to reduce its barrel count by shipping everything to the dump in Hanford, Washington. (Beatty was closer, but it was still refusing shipments from Todd.)

In June, 1981, Todd offered to pay $13,500 in civil fines in an out-of-court settlement — $50 a day for 270 days it was out of compliance with state regulations. The state has agreed, explaining that since Todd is close to compliance, there is no need to “greatly punish” the corporation.

There are now fewer than 200 barrels of nuclear waste on site, and 15 acres, including the once-contaminated area, have been sold. But over half of the irradiated water remains, and it is being discharged into the bay at a rate of 150 curies a year — a six-fold increase over Todd’s original limit. TDH says that it increased the curie limit to help Todd get rid of the water faster and doesn’t claim to have tested the safety of the practice. It will take several years — perhaps as many as five — for Todd to dispose of the water at this rate. And what it’s doing is still illegal under the federal Atomic Energy Act, which does not authorize a state to license the dumping of nuclear materials into coastal waters. But no federal authorities have made any attempt to enforce the law.

All the publicity and public outrage about Todd has had at least one practical effect. Texas lawmakers, in the spring of 1981, passed two bills that will tighten regulatory control over nuclear-waste handlers and establish a new waste repository. Dump sites on flood plains or barrier islands and over fragile aquifers are specifically prohibited.

Rick Lowerre, an environmental lawyer and Sierra Club lobbyist, helped draft the legislation. He believes the regulatory bill is “tough” but will work only with constant citizen oversight and if adequate funds are allocated for enforcement. Some of the safeguards written into the law include: a single system of regulation; a prohibition on storing out-of-state wastes; required public hearings on environmental and socio-economic impacts of site development and on applicants’ financial condition and past history; advance notification of some types of shipments; a prohibition of certain nuclear materials such as plutonium; population baseline and continuing health studies where sites are located; company responsibility for decommissioning, clean-up and perpetual care; improved worker protection and training; civil penalties for violators of $25,000 a day and criminal penalties of $100,000 a day and up to a year in jail. Finally, if the state fails to enforce the law, private citizens may bring suit.

But the Sierra Club is less than happy with the passage of the repository bill, which authorizes creation of a state-owned low-level radioactive dump to store waste created within Texas. All the anti-nuclear groups lobbied against it. But it had the strong support of the state’s medical, utility and uranium mining industries and of Chem-Nuclear, the company that runs the Barnwell dump. (Chem- Nuclear’s Texas lobbyist was once director of the governor’s energy advisory council, and the firm has made no secret of the fact that it hopes to contract with the state to operate the permanent dump.)

Despite the loss on the repository bill, however, Lowerre and other environmentalists are hopeful. They have seen the Todd fiasco lead to enough citizen opposition to get the regulatory bill, and they feel further opposition can prevent any permanent site’s being found for years. They hope they can buy enough time for someone to come up with a safer, more reasonable alternative.

Tags

Betty Brink

Betty Brink has been raising hell in Texas for more than two decades. For the past few years she has been primarily interested in anti-nuclear, utility and energy issues and speaks out wherever she finds a forum. Asa member of Citizens for Fair Utilities Regulation, she is leading the intervention against NRC licensing of a Texas Utilities nuclear plant. She lives in Fort Worth and is the mother of five and grandmother of three. (1981)