This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 2, "Sick for Justice: Health Care and Unhealthy Conditions." Find more from that issue here.

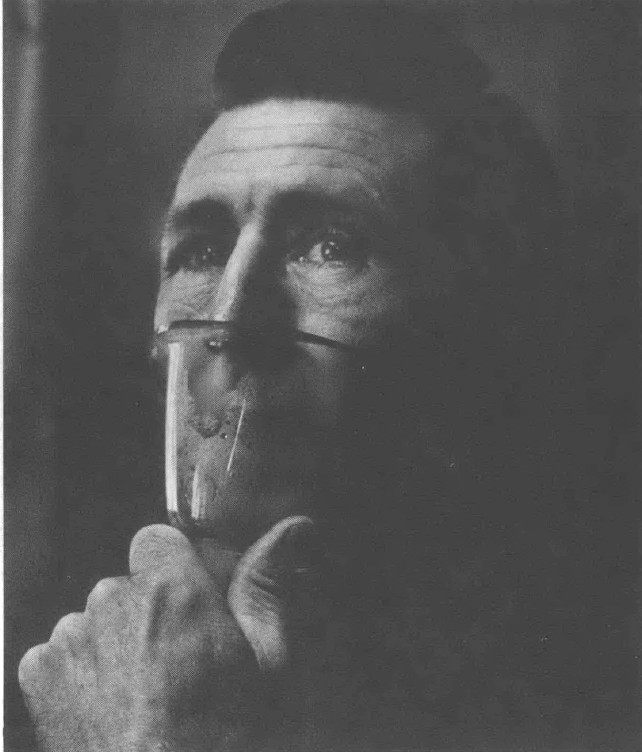

Three years ago, when I first met Talbert Faircloth and his wife, Dora, I found it very hard to believe the story that they told me. Talbert was sick at the time, and jobless and angry. Two years earlier he had been carried breathless out of the cotton mill on a stretcher, never to return to work again. I found it hard to believe that thousands of workers in the South's largest and oldest industry could have been afflicted by a crippling disease for years and not have known that they had it or even what caused it. In time, I learned that Talbert's story — like that of 35,000 other Southern textile workers — was so wrought with truth and so difficult for the region's most powerful industry to accept, that it had been suppressed and ignored for decades.

A year ago, during a conference at Highlander Center in Tennessee, I first heard Les Falk recount his experiences as medical administrator for the United Mine Workers Health and Retirement Fund. The conference brought together doctors, nurses, organizers and health workers from across the South to discuss topics and articles for this health issue of Southern Exposure and to share common experiences in the health field. Les Falk's recollections of the UMWA Fund's battles with entrenched coal company doctors during the early 1950s gave our gathering of Southern health activists a sense of rootedness in our region's tradition of struggle and innovation in organizing health care.

Both Talbert Faircloth — a breathless brown lung victim — and Les Falk — a crusading doctor - are veterans of the South's fight for better health care and are sick for the justice needed to cure our ailing system. This special issue of Southern Exposure brings together moving accounts by victims of health injustice, with the blueprints conceived by visionaries of health care reform. As we go to press, the fruits of Les Falk's labors have been spoiled by a coal industry which has callously used health benefits and medical care as a club to discipline its militant workforce. At the same time, Talbert Faircloth and hundreds of other victimized cotton mill workers, inspired by the miners' earlier black lung struggles, have dedicated their final years to building the Carolina Brown Lung Association and battling the Southern textile industry for compensation and dust-free mills.

Despite the repeated heraldings of a "New South," health has always been a major blemish on the South's robust national image. For a region which still houses the country's largest concentration of poor and underserved people, health care has traditionally meant either "making do" or doing without. Of course "making do" has had its advantages; in spite of the historic absence of the magic white physician, the South has spawned its own non-credentialed healers and backyard herbal cure-alls. From our numerous herbs and plants to our abundant healing waters, a long-buried tradition of medical innovation has been passed from the Indians to the plantation-bound slaves and onward to impoverished and doctorless whites.

A history steeped in such self-reliant traditions enables us today to try bold, pioneering experiments in community-controlled health care delivery. At the same time, however, the dearth of health services makes our region a woefully underserved "medical market" ripe for exploitation by burgeoning health care corporations and a growing medical/industrial complex.

This past decade has witnessed a veritable invasion of the health care field by corporate giants adept at managing sprawling hospital complexes, cutting costs and care, and sopping up the gravy of federal health expenditures to further fuel their cancerous growth. In fact the South houses the corporate headquarters of two of the pioneers of this unhealthy trend — the Hospital Corporation of America and Hospital Affiliates International, both based in Nashville, Tennessee.

As the practice of medicine has shifted from the informal offices of the small-town country doctor to the gleaming corridors of today's space age medical centers, the newly consolidated health care industry has increasingly demanded the production of depersonalized and stratified practitioners of assembly line medicine. The demands of the health industry have had a devastating effect on the education available in our medical, nursing and public health schools. The need for uniformity, efficiency and reproducibility — the basic values of nineteenth-century industrialization — have exacted their toll on today's students and young health professionals.

Many members of our generation have sought careers in the health care field with the hope of translating their youthful idealism into a lifelong commitment to healing the painful wounds of our strife-torn society. Yet as the participants in our opening roundtable discussion recount, the prostitution of the health education process is the most regrettable example of the new corporate domination of health care delivery today.

As we put together Sick for Justice, our preconceptions about health care as an inherently humane enterprise were burst apart. Though health care costs skyrocket, the age-old wisdom of "an ounce of prevention" is scarcely heeded by an industry intent on making profits by perpetuating sickness. The medical citadels of the Dukes and the Vanderbilts expand to the sky, while health care is reduced to the business of delivering commodities which relieve the symptoms of our society's sickness. The chronic ills which prolong and worsen our country's condition are ignored. The harmful side effects of unemployment, recession, and urban decay are overlooked in determining disease causation; prevention and education are dismissed as oversimplified remedies by medical practitioners intoxicated by their own technological solutions.

In addition, though our past has nurtured a rural ethic of oneness with our land and environment, the promises of both longstanding and newlyarrived industries in the South have instead produced bitter, unexpected fruits. Virginia's kepone, along with a host of other chemical compounds, has crept into our daily vocabulary as the perpetuation of our region's overall economic health — in coal, textiles, tobacco and rubber — results in disease-ridden workers, untested environmental pollutants and a potential carcinogenic time bomb. Where we live, what we eat, how we live, and where we work — formerly mundane questions — are rapidly escalating into life and death issues. We can no longer afford to treat health like a poker chip to be bargained away for higher wages or more economic growth. With each new chemical disaster, the insatiable demands of our corporate capitalist society stand in stark contrast to the ecological need for survival, self-preservation and environmental balance.

Sick for Justice was not intended to be a harbinger of environmental doom and destruction, but a tribute to the numerous individuals who have given their lives to building and revitalizing health care institutions across the South. The issue, while in no way comprehensive, attempts to chronicle the struggles of health victims and visionaries by reassessing the region's numerous pioneering experiments in medical education, financing and delivery, thus laying the historical groundwork for redirecting our current system's misguided priorities. Because the solution to our most pressing medical problems lies outside the confines of our present health care system, we have worked to stretch and expand the traditional definition of "health" to encompass quality-of-life questions, political ecology, and little-noticed environmental concerns.

We have learned that organizing people around their health concerns and politicizing the question of adequate delivery of care are enormously more important than throwing dollars and experts at long ignored medical dilemmas. Although our people have been conditioned to expect magic from the great white physician and his wondrous pills, overcoming this professional mystique is the key to building institutions predicated on self-reliance, on the prevention of disease, and the wholistic treatment of individuals as inseparable reflections of their environment. We hope that Sick for Justice will help the victims of the present health care system — all of us — break our dependence on traditional physicians for solutions and spawn a movement across the South to take back control over our bodies, our environment and the health care institutions which were begun to protect us.

Tags

Chip Hughes

Chip Hughes, a former Southern Exposure editor, is on the staff of the Workers Defense League and coordinates the East Coast Farmworker Support Network. (1983)

Chip Hughes, the special editor for this issue of Southern Exposure is an organizer with the Carolina Brown Lung Association. (1978)

Chip Hughes, a member of the Southern Exposure editorial staff, and Len Stanley have worked extensively on occupational health issues including organizing with victims of brown lung disease in North Carolina. (1976)