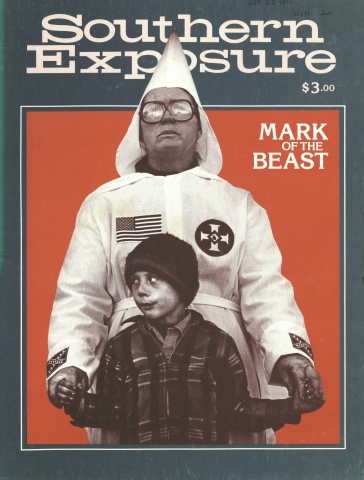

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

He arrived dramatically in Durham, North Carolina in 1974 - swept away from a Baltimore street corner and a heroin habit by an old friend and fellow musician, Imam Kenneth Muhammad, who headed Masjid Muhammad in Durham. Today, Brother Yusuf Salim is one of three owners of a business just down the street from the masjid. The Sallam Cultural Center is a restaurant and showcase for local jazz, blues and other musicians. It is also headquarters for Brother Yusuf's many civic projects, including the Durham Neighborhood Council and the Clean-Up Squad.

Brother Yusuf's perspective on the Ku Klux Klan differs significantly from those of other community activists whose voices are heard in this issue. His philosophy — of concentrating on positive growth rather than aggressive reaction - is rooted in his lifestyle as well as his words.

It's the Clean-Up Squad, you'd better watch out... After two years, children on Durham's West End still sing these words written by VISTA Volunteer Veronica Templeton for a community festival at which this group of children sang.

More often, however, they are seen with brooms, rakes and trash cans, trundling down the street under the tutelage of jazz musician, restauranteur and broom-handling expert Brother Yusuf.

“All right, Brother Pat and Brother Kenny,” he tells the kids, “you sweep it into piles while Sister Sherry picks it up in the dust pan — where’s the dust pan? We lost three last week.”

“Brother Yusuf, can I have a quarter?”

“A quarter? I haven’t seen your lazy self doing anything to deserve it all summer.” He reaches into his pocket anyway and distributes some quarters.

“Here, Brother Yusuf,” says one girl. “I want to give you a quarter cause you’re always doing a good job.”

The days have their ups and downs. But the Clean-Up Squad has, as Brother Yusuf says, “set an example.” People from other parts of town and other cities have asked his advice on setting up similar groups. Volunteers have offered to work with the children on other projects, such as painting a mural. And Brother Yusuf is proud of the changes the Squad had wrought in the neighborhood itself. Older people, previously mistrustful of the children’s behavior, have started asking Squad members to run errands. Local businesses have given some of the children odd jobs. He is especially proud of the time one boy ran to his house to enlist his help for someone spotted lying hurt in a ditch. These incidents shine out among setbacks of fighting, family feuds, trouble with the police. Brother Yusuf is optimistic about the future of the Clean-Up Squad. Oddly enough, though, efforts to get city funding for this youth project have not succeeded.

On one occasion, having been told the wrong time, Brother Yusuf and I arrived too late for a city council committee meeting at which we were going to present one more proposal in our continuing efforts to get some money for the Clean-Up Squad. The council members were heading out of the room, so we had to swing into action quickly. Or rather, Brother Yusuf swung into action, and I stood there holding copies of the proposal. “Good afternoon Brother Councilman.” The mellow diplomat reached out his hand and then embraced one liberal-leaning councilman, who turned beet red. But he recognized Yusuf, and commented, “I hear you’ve been doing good things over there in the West End.” A conversation ensued while Brother Yusuf shook a few more hands and passed out copies of the proposal. A more conservative council member managed to slip quickly around the edge of the circle, but one of his cohorts seemed at least somewhat enchanted with Yusufs demeanor. They all recognized him from the times he had given speeches at City Hall in support of the Clean-Up Squad and the Carolina Builders Institute (a low-income housing and jobs program). These speeches invariably include statements about self-help and words to the effect that: “We aren’t coming here begging; we just want some recognition if you think we deserve it. We are going on ahead, anyway.”

On the way home from this encounter, Brother Yusuf chuckled about the conversations in the lobby. “I guess that’s how they got the word ‘lobbying.’”

Brother Yusuf has strong faith in his one-to-one effectiveness, and this is evident in his attitude towards the Ku Klux Klan and its recent resurgence. He expressed his views on the subject during a recent series of taped conversations.

In my 50 years as an African-American, I remember when the Klan was to be reckoned with. When the Klan was the Klan, this wouldn’t have been possible [being interviewed in his home by a Caucasian woman]. Now, you may be getting a reaction. . . . This diabolic mentality that wants to keep us at our throats, ‘Let’s try to create separation again.’[But] the human consciousness is too awakened now to let any little, small, isolated ideology destroy it.

Brother Yusuf has known the world and the human consciousness through his wide experiences as artist/musician, addict, and as a follower of A1 Islam. As a jazz musician in the ’50s it was easy for him to become part of the circle of musician/addicts. Already at this point he had been influenced by A1 Islam, which was then in its nationalistic stage. He describes his addiction as an ironic blessing. / feel kind of blessed to have gone through the nationalistic period kind of sober. As a heroin addict I had something that kept me from becoming a fanatic racist. Because I was so dependent on my socializing - half of the people I was getting high with were Causcasian brothers, and they used to trust me to cop for them. Even in the nationalistic period I feel that God blessed me to not become fanatical so I wouldn’t become cut off from relations at all levels. . . . Everyone was equal when withdrawal time came.

Today, coffee with honey, not sugar, is the strongest drug Brother Yusuf will touch. But he still has great confidence in his ability to socialize. “Give me a little time with a Klansman — I’ll make him turn in his card.”

The only part of the February 2 civil-rights/anti-Klan march in Greensboro which pleased Brother Yusuf was the endorsement of the event by Reverend Iberius Hacker of the Council of Southern Mountains and the Urban Appalachian Council. Reverend Hacker said that the poor and working class whites were the ones who should be leading the march: that the Klan was an embarrassment to them. Brother Yusuf commented:

I’m just hearing about this. To me, something like that is very significant in human rights. Cause these are Caucasian brothers from Appalachia. That’s beautiful. See, that’s showing growth in consciousness. Let them grow. Ku Klux Klan brother, let him incubate awhile — he’ll probably be a human being. It’s a juvenile mentality - they’ve got to grow. He may have a brother or relative in the same household that feels 180 degrees from him. It’s simply a matter of purging people’s minds, and it’s not going to happen by antagonizing them.

Brother Yusuf disagrees with the tactics of the Communist Workers Party (members of which were slain in the November massacre) as well as those of the February 2 Mobilization Committee. There are, however, important differences between him and others who oppose the strategies of mass opposition. Brother Yusuf is deeply and creatively involved in the community — or rather his several communities of neighborhood, masjid, restaurant clientele, the music world, the city. He belongs to or holds office in several organizations: Carolina Builders Institute, West End Community Action Group, Durham Neighborhood Council, Troy House (a half-way house), the Islamic community. He also holds tutoring sessions for young musicians, helps with musical notation, plays at numerous benefits, and hosts a jazz series on a local educational TV station. Whatever money he manages to come by in any of these endeavors usually goes right back out again to someone in need.

His two favorite organizing methods, though, are greeting everyone as “Brother” or “Sister,” often with a friendly hug — and his role as broom ambassador. Often, he takes his broom and goes down the streets near his home and business sweeping up trash and talking to neighbors. He figures that continuous exposure to his example will get other people concerned about each other and their community.

Although he disagreed with their anti-Klan strategies, Brother Yusuf admired, as people, the five Communist Workers Party members killed in Greensboro last November. He had known some of those who died; most likely had greeted them at his restaurant/nightclub or at one of the many benefits at which he volunteers his skills on the keyboard. And he considers their deaths a tragic waste:

I think we should analyze our strategies, not just throw our energies up blindly. I don’t want to see no more martyrs. . . . Those were good people. I didn’t necessarily go along with the way they did things, but I dug their energy and that they were some beautiful human beings. I sensed love in them. Here’s doctors and things. Either a cat’s got to be a lunatic or areal human being to sacrifice things like hanging out a shingle and not having to worry about nobody shooting him. I knew these were human beings. I think that is enough martyrdom there for dealing with the Ku Klux Klan. . . . Let the thing die. I do not see the Klan as a threat.

His experiences as an addict, and even more so, his continuing career as a musician have put the personable Brother Yusuf in contact with an array of classes, races and creeds, and he thrives on this intermingling. His faith in A1 Islam, however, is what he claims as his guide.

Since we are all actors on this stage of life, the problem has got to be that we have not made reference to our scripts. And my particular script happens to be the Quran. I see the prblem [ today] when Caucasian brothers and sisters are reaching out and being rejected because of a residue nationalist mentality that’s out of date, and not in time with the universal motion of the ’80s. When the Honorable Elijah Muhammad died, that was the signal of the end of so-called black nationalism. That was sign enough for me. His son came right in and turned the whole movement around 180 degrees to universality. The Islamic movement, as long as it has been here, has always been the vanguard of the African-American community. As the Islamic movement goes, so goes the leadership of the African-American community.

In an article on the murders in Greensboro, Bilalian News, the paper of the World Community of Al-Islam in the West, the editor Ghayth Nur Kashif expressed a view that is in harmony with Brother Yusufs: It should be worth noting that the spate of the recent events comes against a backdrop of encouraging advances in some social and political areas by minorities. Just days prior to the Greensboro killings, Birmingham, Alabama, a former bastion of racism — with a Caucasian population of 60 percent - elected its first Bilalian mayor in history. Certainly, America is entering a critical era. Change is inevitable. No less the backlash that comes on the heels of change. It is a time for sober reason. It is a time for unity among all Americans in the face of negativism, confusion and despair. Progress in moral development, racial harmony and meaningful education leads along the road to such a worthy ideal. Brother Yusuf thinks that the spiritual and moral strengthening of the African-American is the most effective strategy against groups like the Klan.

The nigger mentality de-africanized the African. They wore sheets because they knew we were scared of spooks. The Klan was invented to scare niggers, not Africans.

We’ve got too many things to be worrying about [to think about] somebody like the Klan that might be meeting in some club talking about what they want to do - just as long as they don’t do it.

The way I fight the Klan is to communicate with my Caucasian brothers and sisters that are reaching out, and create that positive energy, so we can hold hands and roll up our sleeves and do something together. While that mentality that is dying is dying, we can be working together to make the tombstone of racism. He stops and smiles, as he so frequently does. “Al Humdulilah.” (All praise is due to Allah.)

Tags

Marilyn Roaf

Marilyn Roaf has worked for two years as a VISTA organizer on Durham’s West End, and has collaborated with Brother Yusuf on several community projects, including the Clean-Up Squad. (1980)