Resisting the Klan: Mississippi Organizes

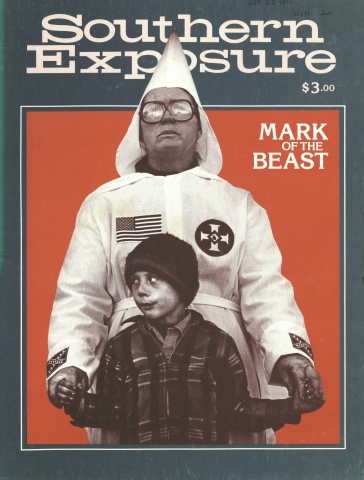

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

If anyone ever writes a history of the anti-Klan movement of the late '70s and early ‘80s. Decatur, Alabama, and Greensboro, North Carolina, will undoubtedly stand out as crucial early battlegrounds — the Fort Sumter and Bull Run in this latest eruption of a Civil War as old as the presence of white people on this continent. But, as in the history of other battles between white and black Americans, the state of Mississippi must again receive special attention. For it was there, months before Klansmen opened fire in Decatur and Greensboro, that more than 2,000 demonstrators from across the country gathered on Thanksgiving Day of 1978 to march against the Klan.

For many of those who came, and for many millions more who read about the event in the newspapers or saw a few seconds of it flash across their TV screens in living color, the Tupelo protest marked a first. Outside the history books, few had ever seen pictures of fully robed Klansmen, brandishing rifles and confederate flags, chatting amiably with uniformed police officers. (“Are those from now?” was the incredulous response to photographs of the scene from one white activist in New York.) Perhaps fewer still, prior to the march, had ever encountered, or even heard of, the organization that sponsored the demonstration — the United League of Mississippi.

But the march was hardly a first for the United League. The group, defined by its founder and president, Alfred “Skip” Robinson, as “a priestly, revolutionary, human rights organization,” has been marching, meeting and boycotting in towns like Tupelo for more than a decade. It has elected blacks to local office. It has won jobs for blacks through affirmative action. And it has left the white-owned business district of at least one particularly stubborn town populated only with “Store for Rent” signs.

In Mississippi, 13 years of such activity means, by definition, 13 years of experience in dealing with the Klan. And people who traveled to Tupelo to march with the League on Thanksgiving, 1978, got a first-hand look at the two key elements of a strategy for combating the Klan that League leaders have extracted from that experience — grassroots mobilization and armed self-defense.

The visitors were warmly greeted by hundreds of local blacks, farmers, students, ministers and factory workers who marched alongside them through the streets of Tupelo and treated them afterward to a Southernstyle Thanksgiving dinner. They saw Robinson climb on one of the pickup trucks leading the march to announce through a bullhorn that the marchers weren’t looking for trouble . . . while two rifles prominently displayed in the pickup’s gun rack announced with no need for amplification that they were, however, ready for any trouble the Klan might start. And they heard the message that Robinson and other League leaders have delivered at countless rallies in Mississippi and across the country — a message that Robinson repeated to these reporters when he first heard about the Greensboro massacre nearly a year later in November, 1979: “The only way you can defeat the Klan is by building a strong base in the community and letting them know you will fight back. That’s what we’ve done in towns like Holly Springs [where the United League was founded and still has its central office]. And we haven’t seen the Klan here for several years. Because they know we’d be ready for them.”

Building a Community Base

En route to an August, 1979, march in Ripley, Mississippi, to protest the police beating of a young black man arrested for drunken driving, Skip Robinson outlined the League’s methods for building grassroots support.

“I never just go someplace. I wait till someone calls me with a problem.” After the initial contact has been made, the legwork begins. Robinson and other United League members go house to house, street by street, through the black community. “We have workshop meetings. I might never mention the United League. We go by streets. Sometimes we’ll have three meetings in one night.

“Seventy-five percent of the people have problems,” he continued. “If you talk about those, people listen. A lot of problems can be solved, dealt with. But somebody’s got to offer hope. After I tell them what they can do themselves, then I tell them about the United League.”

It takes time to build a strong organization, of course, and it isn’t easy. But the United League is committed to the slow and difficult process of building from the grassroots up, rather than playing for a few splashy headlines and messages of support from Washington or New York. League activists point out that passage of the Civil Rights Act did not give blacks freedom and equality, that the Civil Rights Movement of the early ’60s barely reached many small towns in the Deep South, especially majority white towns in north Mississippi like Ripley.

“In Ripley, at first, I couldn’t get five people together,” says Robinson. “Now [less than a year later] I fill the funeral home at every meeting. That’s 300 people.”

The United League has seen the same pattern played out in towns throughout the northern half of the state and reaching up into Tennessee. “Usually one or two people contact Skip when they have a problem,” explained George Williams, another long-time League organizer and leader. “And usually every town in Mississippi has the same problems — police brutality, the Klan, thefts of black-owned land.”

Once people like Robinson and Williams have come to offer hope, help and experience, a local chapter is established. In most instances, the mainstays are women. “Just about every chapter we start, we get more women involved than men,” Williams observed. And they are the ones who carry on the task of building the organization, planning protests and boycotts, and above all convincing people that they can stand up against the social violence symbolized by the Klan.

In Ripley, for example, the first stop for a United League car driving into town is the beauticians’ school run by Mrs. Hazel Foster Christmas. She is the person who organizes meetings and reminds those who come that “We can talk all year, but we have to do something.... My son is in sixth grade and he’s having more problems the older he gets. I won’t stand for my boy to go through what I did. It’s going to come down soon, and we’re going to have some kind of action.”

After a local black man was beaten by whites at the factory where he worked, Christmas recalled, “I told him to tell them he was not afraid to die. Because they think they can scare you.”

Much the same sentiment was expressed by grassroots League activist L.B. Groover as he stood outside the Holly Springs Fire House on election day, 1979, passing out campaign literature and sample ballots for candidates supported by the United League. A confident man who runs his own masonry contracting business, he responded without hesitation when asked how he coped with life among Klansmen and other racists. “You walk up to them and tell them what you know. That it doesn’t scare you, that you are going to be yourself. I just be what I am.”

When a man named House was mentioned in connection with the Klan, Groover replied, “House used to be in the Klan. But he may not be now. A black guy put him down, beat him up good a couple of years ago, right up in town. The guy had to be pulled off him. For a while blacks boycotted his auto body shop and put him out of business. When he opened up again, he treated people better.”

Such boycotts, frequently directed at an entire downtown business district, have been a regular and powerful tactic of United League organizing against Klan and police violence. In Byhalia, for example, “There had been a black killed nearly every week” when Robinson was asked to help put together a local chapter in June, 1974. “People took their guns,” Robinson recalled, “and we laid it out to them. We told them that if any more people were killed, it would be a life for a life. We said the last black had been killed in Byhalia. And there has not been another since then.”

At the same time, the League began a boycott of white-owned businesses in town and presented the mayor with a list of demands, which included the hiring of blacks in stores and schools. The boycott lasted more than a year and a half. It was a bitter, often violent, confrontation. Without black dollars, many businesses closed their doors, and most of them never reopened. Those that did.,open again did so away from what had been the downtown business district. What was the center of Byhalia in 1974 now looks like a Western mining town after the gold ran out. The buildings stand deserted, some with merchandise still piled inside.

There was no total victory for either side. But United League activists insist the essential message got across. “Folks said it was a kinfolk town, we couldn’t do anything. But we waved that cardboard around and they had to do something,” said Perry Anderson recently. He had been chairman of the United League in Byhalia during the boycott. “We didn’t get all we wanted. But we showed them Negroes was something.”

George Williams points out where a huge wooden cross still stands in a field on the outskirts of Byhalia, where another, this one strung with electric lights, perches on top of the town water tower. But the lights haven’t been turned on recently to announce a Klan gathering, nor have blacks spotted any dead rabbits placed along the road — the sign formerly used to announced that the Klan would be gathering under the wooden cross.

And the United League still meets regularly in a black church in Byhalia, where on occasion members hear Skip Robinson deliver his own version of liberation theology. Robinson is a skilled preacher who knows when to use the Bible . . . and always has one handy in case the occasion arises. “If you want to organize people in Missis- sippi, you’ve got to be associated with a church,” he explains. “If people stop going to church, it’s because they’ve lost faith in the leaders, not in a Supreme Being.” He does not preach nonviolence, however, and is generally critical of black religion. “Most black preachers are still preaching slave religion,” he maintains.

If Robinson relies heavily on the Bible for his style of oratory and organizing, he does not rely on it for protection. “I’m like one of those oldtime Western preachers,” he said with a laugh one day during the November, 1979, election campaign. As he spoke he held out his open briefcase. Lying at the bottom were his Bible and a .38.

The pistol in the briefcase and the insistence on a strategy of armed selfdefense were both Mississippi traditions before the United League came along. Reminiscing about the civil rights movement of the ’60s, Julian Bond recalled “a big debate in SNCC once about carrying guns.” The debate came to an abrupt end after “two or three guys from Mississippi said, ‘This is all academic. We been carrying guns. I got mine here.’”

The young SNCC workers had simply learned the lesson preached by older Mississippi supporters like Hartman Turnbow, an almost legendary figure who once warned Martin Luther King that “this nonviolence will end you up in the cemetery.”

“This old guy, Hartman Turnbow I remember him,” Bond recalled. “He used to carry an army automatic in a briefcase, and it’s funny to see a man who looks like a farmer and is dressed like a farmer in coveralls and boots and, let’s say, an old hat, with a briefcase. And he opens the briefcase and nothing’s in it but an automatic.”

Skip Robinson dresses like the highly successful building contractor he once was, but he comes out of the same tradition of unflinching resistance. And the gun in the briefcase has stood him and the United League in good stead.

“The Klan has not been seen in Marshall County since early ’78,” he said recently. “We was ambushed when we came out of the office in Holly Springs. There were six Klans standing across the street and when four of us came down the stairs they started shooting. I jumped over my brother’s car and got my gun out of the briefcase. When I started shooting, they took off and one of them dropped his rifle. I was hit in the leg, but not bad. The bullet just glanced off my leg.”

The United League members jumped into a car, roared past a police car that was giving desultory chase to the fleeing Klansmen, and blocked the getaway car’s escape. One of the young men inside turned out to be the police chiefs son. Nobody was ever arrested in connection with the incident. But the police chiefs son “hasn’t been seen since.” And neither has the Klan in Marshall County.

The United League’s 13-year history has been marked by several similar incidents. Right around the time of the Thanksgiving Day march, for example, a black man was shot by a Klan member in Okolona. According to Robinson’s account of what followed, several hundred blacks prompt ly gathered, guns in hand. An apparently nervous chief of police called up local United League activist Dr. Howard Gunn and asked him to come down to the police station to talk things over. Against Robinson’s advice, Gunn decided to go. But in keeping with United League tradition, he decided to take along some friends with their guns. That proved to be a wise decision. When he arrived at the police station, the lights were out and the police chief was nowhere to be seen. As the United League members tried to make their way home, they were ambushed.

“Twelve Klans opened fire into the station wagon,” Robinson recounted. Gunn and his companions fired back. “Over 100 rounds were fired. And when the shooting was over, six Klans were lying in the street and six were running. One of the six in the street was dead.

“The Klan never said anything about it, the police never said anything about it, the press never said anything about it,” Robinson continued. “But after that we never saw no more Klan in Okolona. We know they’re still there but we never did see any signs of Klans in uniform.”

Beyond Fighting the Klan

By relying on grassroots mobilization and armed self-defense, the United League has been able to stop the Klan in several counties. But that, in the view of League leaders, is only a beginning, just as the Klan is only a symptom of the problems confronting blacks in Mississippi and across the United States. “The Klan isn’t our main problem,” Robinson states categorically. “You have to look at the system that allows it to happen. This country is moving to the right, and the system is encouraging it to happen. I’m worried about the man in the three-piece who is elected to the Senate, or the judges and the doctors who send our people off to prisons and carve them up in hospitals. They are more of a threat to us than the Klan dressed in white sheets.”

Robinson grimly predicts, “There is going to be a civil war in this country in the ’80s,” a sentiment echoed by a young United League activist who was driving voters to the polls on election day. “Now with the Klan coming up again,” he remarked, “black people won’t take that anymore. There’s going to be a big shootout. I hope it doesn’t happen, but sometimes I have a feeling it will take a real shootout to wake people up that they have to live and work together just to survive.”

As the United League sees it, the Klan is just one of many mechanisms used to keep blacks powerless and afraid. “Fear has been used to take thousands of acres of land from blacks,” Robinson contends. “And now black and colored people don’t control nothing. From 19 million acres, we only have two million left.”

The only way to free people from fear and powerlessness, in the view of Robinson and other League leaders, is by building pride and power. That is what marches and meetings and boycotts are all about, aiming to awaken not “the conscience of white America” but the “sleeping giant” of black America.

“Our strategy is to use whatever it takes for people to organize a grassroots movement around their needs,” Robinson explains. “Boycotts and demonstrations never change people’s hearts. That’s the mistake Dr. King made.

“But black people are a sleeping giant who lies in a shallow grave. And there is one thing I am proud about. For all the time we have been enslaved, there was one thing the system didn’t understand — that one day we would come back after it, with blood in our eyes.”

Tags

Andrew Marx

Andrew Marx and Tom Tuthill are staff writers for the Liberation News Service, 17 West 17th St., New York, N.Y. 10011. (1980)

Tom Tuthill

Andrew Marx and Tom Tuthill are staff writers for the Liberation News Service, 17 West 17th St., New York, N.Y. 10011. (1980)