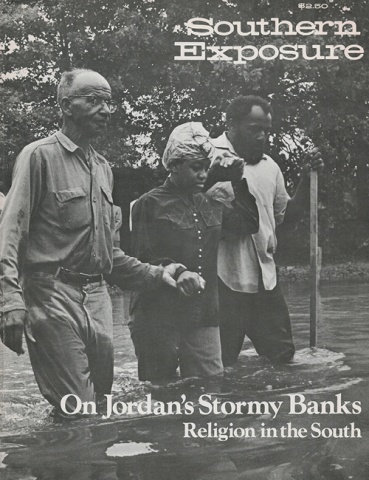

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

In 1895, at the age of 80, Elizabeth Cady Stanton published The Woman's Bible, a critique of woman's role and image in the Bible. Pointing out that the scripture itself was a source of women's subjugation and dismissing the story of Adam's rib as a “petty surgical operation," The Woman's Bible was considered scandalous and sacrilegious, arousing protest from clergy as well as women suffragists.

For centuries, the theological view of woman which undergirds the policies and structures of the church has followed a strictly conservative interpretation of the Bible. Consequently, no other institution in society has more overtly and more consistently kept women in their “place" than the church. Whenever women attempted to become involved in the social movements of their day, they met swift and harsh response from the clergy.

A pastoral letter from the Council of Congregationalist Ministers of Massachusetts is typical of the reaction to women's involvement in the Abolitionist Movement:

The appropriate duties and influence of woman are clearly stated in the New Testament .... The power of woman is her dependence, flowing from the consciousness of that weakness which God has given her for her protection .... When she assumes the place and tone of man as a public reformer. . . she yields the power which God has given her . . . and her character becomes unnatural.”

The Women abolitionists persisted, however, and were soon drawing their own parallels about liberation. South Carolinian Sarah Grimke was among the most outspoken:

All history attests that man has subjugated woman to his will, used her as a means to promote his selfish . . . pleasure. . . but never has he desired to elevate her to the rank she was created to fill. He has done all he could to enslave and debase her mind . . . and says the being he has thus injured is his inferior. . . I ask no favors for my sex ... All I ask of our brethren is that they take their feet off our neck and permit us to stand upright on the ground which God designed us to occupy.”

Forced to beg, and occasionally demand their rights, first as professional workers, then as laity, and lastly as clergy, church women have consistently been in the position of having to do battle for their own rights in order to carry out their moral concern for the rights of others. In the course of these struggles, women began to discover their own capabilities as well as the restrictions they faced. Though they were able to operate effectively through separate "women's work" organizations such as the ladies aid and missionary societies, they continued to find themselves in the position of the powerless and the petitioner in regard to official church policy.

Methodist women in the South have long played a leading role in this fight to gain a position within the church from which they could express and implement their own concerns. At the Methodist General Conference in 1880, Frances Willard, newly elected national president of the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), requested ten minutes to bring greetings to the body. A two-hour debate on the request followed. One delegate threatened to use all parliamentary measures to block her appearance even after two-thirds of the delegates voted to hear her speak. Finally, she sent a note “to her Honored Brethren” saying that she declined the ten minutes they had been so kind to allow her.

Eight years later, Frances Willard returned to the General Conference as one of five elected women delegates. The Committee on Eligibility voted eleven to six against seating women, stating that the vote to permit lay participation had referred only to men. The ensuing floor debate continued for one week, and the women eventually lost by 39 votes. The gentlemanly delegates then voted to pay their travel expenses.

Attempts to become a part of the larger church structure continued unsuccessfully, despite the fact that women continued to carry the weight of the Methodist Church's local programs and missions. Their community work went practically unnoticed in the larger picture; records of the participation of women in church history are as scarce as hen's teeth.

But participate they did — funnelling their energies into separate women's organizations that became vital to the church as a whole. At first, men viewed the Ladies Aid Societies as a welcome right arm, a "service arm" of the church, functioning at the behest of the male pastor, with no share in making church policies. But under the effective leadership of women like Belle Harris Bennett and Lucinda and Mary Helm, local women's mission societies, which had sprung up all over the South, were united in a region-wide Woman's Home Mission Society. Autonomous and democratically organized, this new structure gave Southern women an unprecedented opportunity to gain administrative skills, self-confidence and experience in running their own affairs. Under it auspices, Methodist women introduced the settlement house movement to the South and sought to implement the concerns of the social gospel.

Feeling the need for full-time workers, the Woman's Home Mission Society petitioned the general conference in 1902 to create the office of deaconess, thus providing recognition for a new breed of professional women church workers. When the request was presented to the conference, the delegates feared that such official recognition would lead to women aspiring to the ministry; others thought it would replace the minister entirely. One man simply said, "this is heresy."

In order to allay their suspicions, Mary Helm wrote an article in Our Homes magazine (the official publication of the Home Missionary Society) explaining in part that a deaconess is not a preacher and not ordained. She also felt compelled to explain further that a deaconess does not wear a nun's habit and is not a begger. Typically each new gain was won only against the bitter opposition of those who feared that women's work in the church might serve as a dangerous foothold for feminism.

The movement for laity rights for women in the Southern Methodist Church was given impetus by an attack on the hard-won autonomy of the Women's Home Mission Society. Without consulting the women, the Board of Missions combined the Society with the more conservative Foreign Mission Society and subordinated both under its male-dominated administrative structure. Without a voice in church policy, women leaders had no choice but to submit or resign. In response, they launched a campaign for laity rights which paralleled the larger, secular movement for woman suffrage. After winning the right to serve as voting delegates to the General Conference in 1918, Southern women began the long struggle for ordination.

When the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, convened with the Methodist Episcopal Church, North, and the Methodist Protestant Church in a unifying conference in 1939, women were still battling for the rights of clerical ordination. The 1938 General Conference of the Southern Methodists had left intact its church policy that “Our church does not recognize women as preachers, with authority to occupy the pulpit, to read the Holy Scriptures, and to preach as ministers of the Lord Jesus Christ; nor does it authorize a preacher in charge to invite a woman claiming to be a minister . . . to occupy our pulpit to expound the scriptures as a preacher. Such invitations and services are against the authority and order of the church."

Following the union of the three branches, the newly created Women's Division of Christian Service included within its structure a standing committee on the role and status of women, with similar committees on all organizational levels. One of its major objectives was to secure full clergy rights for women. It was seventeen years later, in 1956, after extensive debate, that clergy rights were finally granted. The General Conference that year had little alternative — it had received some 20,000 resolutions from women's groups across the country.

The organization of the Women's Division provided a valuable and effective channel for women's full participation in the church structure. The Division became one of the most powerful and active arms of the United Methodist Church, particularly in the realm of Christian social concern.

It is in the area of racial justice that the Women's Division has perhaps had the most impact. A Commission of Race Relations was created as early as 1920 in the Southern church, at the urging of Belle H. Bennett. The Commission helped lay the groundwork for women's involvement in the interracial movement after World War I. In the '30s, Methodist women were active in the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, founded by Jessie Daniel Ames, a Texas Methodist.

Following World War II, the Division organized “demobilization workshops" across the country. Among other things their goals were to develop strategies for transforming defense industries into peacetime industries, to conserve gains achieved for minorities and women in job opportunities, and to insure the continuation of integration efforts.

In the late '40s, Dorothy Tilly of Atlanta was the moving force in initiating and promoting an organization known as The Fellowship of the Concerned, an ecumenical and inter-religious group with members from 13 Southern states. The Fellowship was primarily concerned with achieving justice in the courts, and later, with mobilizing support for the 1954 Supreme Court decision on school integration. Mrs. Tilly, who served as jurisdiction secretary of Christian Social Relations in the Woman's Society of Methodist Women in the southeastern region, had a ready-made base of many hundreds of Methodist women who played a major role in the organization.

When Truman created the Commission on Civil Rights, Mrs. Tilly was among its nine members. The Commission released its report in 1947; in December of that year, she reported its findings to the annual meeting of the Women's Division. As a result of her report, a special study on human rights was initiated for Methodist women in 1948-49 to help prepare Methodist women for the changes coming in the '50s.

As the decade of the '40s drew to a close, the nation was beset with McCarthy's witch hunts and Communist labels. The Women's Division, sensing the need for an informed and concerned electorate, authorized a National Roll Call for Methodist Women urging their political participation at all levels. The call that went forth stated in part:

I have set before you life and death . . . choose life . . . World peace, freedom, justice for all mankind are not achieved by apathetic, indifferent Christians. Conflicts in ideology are not resolved by failure to face controversial issues. Community practices are not changed by worshippers of tradition — born too late. Good laws are not enacted and enforced by citizens who fail to vote. The rights to food, a home, a good life will not be guaranteed the children of the world by a society geared to materialism and personal profits. The UN will not be strengthened by people with no knowledge of its achievements nor of the issues confronting it.

In 1951, the Women's Division published an 800-page volume of State Laws on Race and Color. This marked the first time any effort had been made to collate the state and local laws of the nation in regard to race. The vast resource was compiled by Dr. Pauli Murray, a young, black woman lawyer from North Carolina. Following the 1954 Supreme Court decision, Dr. Murray prepared a "Five Year Supplement." Her distinguished work was hailed as an important landmark in providing factual data about such laws. For Methodist women it provided needed information about their own state laws and local ordinances.

The Women's Division adopted in 1952 its first "Charter of Racial Policies," a commitment to full and equal participation that was later ratified by all the participating conferences. When the 1954 decision of the Supreme Court was announced, the Methodist women, who were in session at their Quadrennial assembly, immediately adopted a resolution of gratitude and support, and called for Methodist women throughout the country to work for its implementation.

The civil rights movement of the '60s was also a time of involvement for Methodist women, calling forth a nationwide upsurge of support as well as a groundswell of fear, violence, and opposition. Women of the church played important roles on both sides. Great numbers marched, raised bail money, and wrote letters in support of civil rights legislation. Others supported violence, and the philosophy of racial segregation.

As the Women's Division moved into the decade of the '70s, it renewed its emphasis for the full and complete integration of women into positions of lay and clergy on all levels. The 1972 General Conference created a Commission on the Status and Role of Women, mandated to work with all the agencies of the church to build structures that provide equal participation and responsibility of women in every part of the church's life. The Division has also established new channels for encouraging women, both lay and clergy, to develop and utilize their skills for effecting change in the present male-oriented church and society.

Tags

Thelma Stevens

Thelma Stevens, originally from Mississippi, has been a "full-time church worker" all of her adult life. While a student at Hattiesburg State Teachers College in the late '20s, she became involved in the YWCA and organized interracial meetings between the students from the college and black schoolteachers in the town.