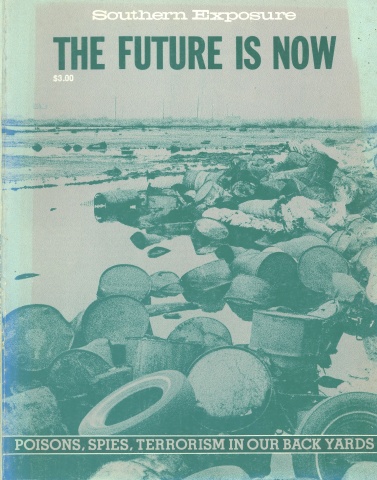

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 3, "The Future is Now: Poisons, Spies, Terrorism in Our Back Yard." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

This story begins with the Farm Security Administration, a New Deal program which bought, improved and redistributed land. In the South, a few of the projects were designed specifically for black tenant farmers. One such project was in the Douglas Community of Haywood County, West Tennessee.

The Tennessee Farm Tenant Security Program, known simply as “the Project, ’’purchased about 4,000 acres from Will Douglas, a white farmer, then terraced, fenced and divided the land into 36 plots ranging in size from 85 to more than 100 acres. The Project built a house on each property, along with a smokehouse, a barn and a chicken coop. Forty-year mortgages at three percent interest allowed families, who were usually tenants on the same piece of land, to become property owners.

A great deal of the Jeffersonian ideal of the virtue derived from land ownership underlay this and similar federal experiments of the 1930s. Rexford Tugwell, head of the Division of Subsistence Homestead and the Resettlement Administration - New Deal agencies which preceded the FSA - envisioned a federal policy that fostered the creation of an economic base for financial security, improved education, political reform and perhaps even the development of democratically controlled institutions such as cooperatives and health clinics.

At the Douglas Community, that vision embraced black farmers and directly confronted racial inequality in the South. As Jesse Cannon, Jr., a second-generation member of the Project, says of his parents and others who first bought land in 1939: “A lot of people who were tenants living on the plantation suddenly became property owners; they became independent-minded, so to speak. They had some say-so in their livelihood, and they didn’t have to depend on the white landlord.

“They were just part of a few blacks at the time who had property and could say, ‘Look, I can say what I feel, because you can’t kick me off my land. This is mine. ’It made a big difference, ever so gradually.”

The following interviews detail the relationship between land ownership, race, and the lives of people over 40 years and two generations.

Land

Jesse Cannon, Sr., lives in the house he first moved to on the Project. He is nearing the age of retirement and like many others began working in nearby factories when the income from the farm was inadequate. He assumed responsibility fora family at the age of 13 when his father died. He eventually married and raised eight children of his own.

Jesse Cannon, Sr.: Back in the early days, I was trying to do better all the time but it was hard. In 1936,1 moved from Tipton County to Haywood County and I was a sharecropper. I improved myself a bit and I went to renting. But I had a situation concerning the rental check that the government was paying people not to plant crops. This landlord didn’t want me to have a rental check, but the government official said I was entitled to one.

I got a card one evening when I come out of the field telling me to come to Brownsville to pick up the check. So I took the card up to the landlady. I said, “If it’s your check, I want you to have it. If it’s mine, I want it.” She said, “It’s my check. It’s my land, it’s my check. You don’t have no land and you don’t have no check coming.”

I said, “Well, I’d like for us to go and let em explain it.” She wouldn’t go. So we went on over to Brownsville and picked up the check, me and the other fellow that lived on the place.

She left word at our house when we got home that evening late to come up there to her house. The next morning we decided we’d go up there, and so we went up there and she set out at us. She called me a Nicodemus — I went out by cover of night — and the other man was there, she called him a Judas — he betrayed her. She wanted us to give up the checks, but we wouldn’t give them up.

Her nephew come by the house and said, “Jesse, you decide to give that money up.” I told him, “No, the government said it’s mine, I want it.”

“Well, I tell you one thing,” he said. “If you keep it, it’s going to cost you a hell of a lot.” Well, we had to go up in her yard to get water in that old well, and after a couple of days, I got to trying to consider things in proper place and I said, “I’m going up there in her yard getting water and they could say I insulted her some kinda way.” I started to leave the crop, started to just move by night, but I said to do that would be a bad mark against me in years to come. I might want to farm again and it would hurt my children. So we decided to give the check up, make that crop, and leave the next year.

After I gave it up, a month or better, she came by the house one day and she was telling us, “Jesse, before you got my check, I passed the road and looked at my crop and said, ‘It was so pretty,’ but when you had my money and wouldn’t give it to me, I passed the road and looked at it and said, ‘I wished there was some way I could burn it up.’” She was happy then, after she had the money.

When she left I went on back in the house and I told my wife, “You know we were in danger when I had that money.” I related what she told me. I said, “She could have come here and set us afire overnight.”

Then the landlord, she told me, in August, “I’m going to have a lawyer come up here and we’re gonna fix up some papers so we won’t have any trouble next year.” So I went on down [to the lawyer’s]. Mr. Douglas wasn’t there, but finally he come about 7:30 that night. So I told him what I come down for. “I do not want to sign this paper,” I said, “but I’m living there with that lady. I have to go up in the yard to get water every day and I’m afraid not to sign.” I signed it and I went over to Brownsville to the ASC [Area Soil Conservation Service] chairman, Mr. Tom Freeman, and I told him what had happened. I told him I didn’t want to sign it but she requested it. So he told me, “Say, that won’t work. That will never happen. That’s just like highway robbery.”

I moved after I got that second year’s crop but this paper was signed in August before I moved. So the following spring, I was on another man’s farm and I got a notice one day to come to Stanton to the bank and pick up my check. When I got there to get the check, they told me my old landlord had my check. I said, “Got my check?” They said, ‘Yes.” I said, “What’s she doing with my check?” They said, “You signed a paper for her to get that check. Said she loaned you some money to make that crop. Stated on that paper she was entitled to get that check.”

I left the bank and took the bus or train to Brownsville and went to Mr. Freeman. I said, “The thing you said couldn’t happen, done happen.” “What thing?” he said. And I explained about the paper and how she had my check. He said he would have the whole ASC committee meet and straighten it out.

So we met. They were five white men, Mr. Douglas, he was one, and me. Mr. Douglas said, “I don’t remember your saying anything about not wanting to sign the paper.” Now they were five white men, so I looked down a while and then I looked him straight in the eyes and I said, “Mr. Douglas, you’re a white man and I’m a Negro and I can’t call you a liar and I’m not trying to do that, but don’t you remember how I come to you in August at 7:30 in the evening. You were late and I said that I did not want to sign the paper but I was afraid cause I lives on her land and had to go up to the house for water.” I was looking him in the eyes. Then the old man looked away and said, soft as can be, “I reckon I do.”

The chairman sent them out and told me I could get the check back. I said, “Will you get it back?” He said, “No, but I’ll tell you what to do.” So he told me, “Write to Mr. Wallace, Secretary of Agriculture, and tell him what happened.” So I wrote and sure enough about two weeks later I got a letter saying to come to Brownsville again for a meeting with the old lady, me and the other man who was still renting from her. Well me and him got there first and she came with her nephew and said, “The thieves beat us here.” She called us thieves.

They told all of us we were meeting to settle the matter of the check and if we didn’t want to do it, it would have to go to Washington. Now the other man, whose check she had, he was willing to give her a third for peace sake. They asked me how much I was willing to give and I told them, “Not a dime. It’s mine and I want it.” Well, we talked some more and then we took a break and the other man said he was willing to give half. Now that weakened my position and made me seem uncooperative and I was afraid if we didn’t settle it, I would have to go to Washington — I wouldn’t have had to but I thought I did — and I didn’t have money for that so I agreed to give her a third.

But that only made me more determined to get my own place and when the Project started I went down to sign up. I had a chance to own my own place and I jumped at it.

The Lord blessed me and my family and saw us through this. We got the check back and got our own place. This whole area of the Project was Mr. Willis Douglas’s place, you know, the man who drew up the papers to take my check away. In fact, when we came on the Project, our house was the one they had made out of Mr. Douglas’s old house.

Tom Rice is another of the original members of the Project. He runs a small store very near his house and is the father of 13 children.

Tom Rice: Master Stanley H. Rice was the supervisor over the Project, we didn’t have bosses then. The first year our supervisor had a meeting, called us together in a meeting, and he told us we had 40 years to pay for one of these units but he said, “My advice to you is to pay all you can.” He told us, “If you can’t pay way ahead on it, then I advise you to pay three years ahead of schedule and if you have a bad year why you still won’t be in no cramp. You won’t have to pay anything cause the payments have already been paid.”

So I taken in his advice. I made three payments on it and paid it out. But I had a stream of luck. Wien I started to buying, cotton was five cents and when I got set up to sell, cotton jumped from five cents to 30 cents and from 30 cents to 40 cents and I was making good crops all the way from 20 to 25 bales of cotton and all the hay and corn the barn could hold and I put it all to good use. I gave it to them as I made it.

I started the store in October, 1947, that’s when this building was built. I started a theater here in ’49; I ran it about two years. We had Floyd Nelson from WDIA* and B.B. King. They were the two best that I had play here. I had several other little bands. B.B. King played here off and on for two years until he left and got famous.

There was other music, too. We used to have the 8th of August celebration to celebrate the Project. [The day also commemorates Emancipation.] The Project would all meet together and give a big free dinner, everything was free, and invite people from different counties around to celebrate with us on that day — feast with us on that day. We’d have music to entertain the peoples; the Fredonia Band and the Miller Brothers’ Band and sometimes we’d have music machines [jukebox] to entertain the people and everything to eat or drink was free.

Freedom Village

by Ella Baker

The residents of the Douglas Community were not the only blacks in West Tennessee to join the struggle for voting rights in the 1960s. In 1961, Ella Baker wrote this story for the Southern Patriot from neighboring Fayette County describing the plight - and the determination - of families who faced repression for their activism, and who did not have their own land to protect them from economic reprisals from the white community.

It was around the New Year, 1961, that I visited Freedom Village in Fayette County, Tennessee.

“Freedom Village” is the name Negro tenant farmers have given the tent city into which they moved when they were evicted by white landowners after they registered to vote.

Eight families were living there in early January, and hundreds more may soon follow if the federal government is not permanently successful in its court efforts to enjoin further evictions.

The olive-drab tents without floors, surrounded by inches of mud and mire; the darkness within these tents that are lighted by kerosene lamp and heated by wood stoves; the not-too-well-clad children crowded into the tents or squashing around in the mud; and the hungry shivering dogs wandering about: all of this painted a picture of anything but hope for the new year.

But the real tragedy is that in the wealthiest country in the world, in the jet-propelled atomic age of 1961, human beings could honestly say that their mud-floored tents were more comfortable than the shacks they formerly called “home” for five, 10 or 30 years.

Yet this is what those tent-dwellers told me, and this is the true story of a Negro sharecropper’s life in Fayette and Haywood Counties.

It is a story of years of hard work and little or no money; it is a story of big families living in one-or-two-room shacks.

There was Willie Trotter, 36, who has six children ranging in age from 14 years to eight weeks. From the 10 bales of cotton he made, he received less than $160 “profit” for the year.

Mr. Trotter was glad to have his small floorless tent, because the house he lived in before had two rooms, but one needed repair so badly that the family lived in one room. Freedom Village meant better living to this family.

Walker Allen Mason, 27, made five bales of cotton and ended the year with about $125.

These two farmers were well-off compared to Mrs. Dora Turner, who had worked the same farm for 38 years in her own name and 20 years before that with her mother.

When typhoid-malaria killed her four brothers, Mrs. Turner plowed 12 years and paid off a $2,200 debt which the landlord said her mother owed. Last year, 1959, she ended owing $50.

This year, 1960, she received six checks of $30 each - a total of $180. When she was evicted after voting, she was confronted with a bill for $600, she said. Her 1960 share was three bales of cotton. This she had to give to the landowner and was told she still owed $291.95…

Freedom Village faces the winter with prospects of having to house many more families and the demands of the moment leave little time to think about the final outcome.

Floors have to be put in tents, land has to be drained and packed to offset the mud, sanitary facilities have to be improved, and — hopefully — electric lights and windows secured for the tents. At the same time, families must be fed and clothed.

Despite this yeoman task, there is talk in Fayette County about buying land for group or cooperative farming; about work projects, and about small industries that will hire Negroes.

What does the future hold? What is the answer? I wish I knew. But of this I am sure.

The deprivations and the hardship which the evicted Negro farmers now endure are revealing for all the world to see both the general plight of the Southern sharecropper and the machinations that have been robbing Negroes of the right to vote.

And the determination of Negroes to vote in Haywood and Fayette Counties is a sure indication that a new dawn of freedom is breaking through the age-old social, economic and political discrimination that has blighted the lives of both whites and Negroes in the South.

Jesse Cannon, Sr.: Different families would bring different kinds of foods. We’d have representatives from various parts of the country — even as far as Washington — attending our meeting. They would lecture to us and after the meeting we would spread the food and sit down and eat like one big family and then we’d go home. We enjoyed that tremendously. We looked forward to that affair every year.

We did other things together, too. We used to work together cleaning off the roads and what not. If something needed to be done down at the school, we’d go to school and clean up the campus grounds there. And that was just lovely — that mens could get together and work and beautify the place. We did that and I enjoyed every year that I’ve been here.

I was happy and I went ahead and was able to purchase. It puts some responsibility on a person, whereas if I was still sharecropping I’d be looking to the man for whatever is necessary, but now I have to look to myself.

School

Tom Rice: I really can’t explain how important it was to own the land. It meant a whole lot to me. First, I could keep my children in school and train them the best I knew how to train them. When I was working other land, I didn’t have time to train them and I didn’t have money enough to send them to school.

Born and raised in the Douglas Community, Jesse Cannon, Jr., returned after graduation from medical school to practice in the Douglas Community Health Clinic, which is in Stanton, Tennessee, seven miles from Douglas. His father, Jesse Cannon, Sr., was an early member of the Project and an original member of the community group that organized the clinic.

Jesse Cannon, Jr.: I was born here. I attended first through eighth grade at the Douglass School. At that time actually it went to the tenth grade. When I reached the eighth grade it was subsequently changed over to a grammar school.

Douglas Community at that time was totally a farming community. There was no other economic base at all and everybody that you knew, everybody that you grew up with, was farm kids. School was geared around your farming activities. You were out during the summer months to till the cotton, you went back to school for the month of August and part of September and then you were out again a couple of months to pick cotton. Sunday was your day off. That was your only free time and most of the kids in the community, the boys and girls in the same age, would kinda take turns going from house to house each weekend to play softball or baseball, whatever else. Your life revolved around your family because that was it with the exception of Sunday afternoon when you got a chance to get out with the other kids.

Most of the families were large families; for instance, my family was eight kids. I’m the oldest of eight kids. Everything was within the family unit; we were in our own little world. We had a lot of food because we were farmers. We didn’t have any money and we worked like dogs and we felt that was the way it ought to be. We were sheltered from a lot of the things in the outside world.

Let me tell you a little bit about Douglass Junior High School and what that was like. Of course, it was an all-black school. One that had people who lived in the community for the most part as teachers; some were from Brownsville. They were an extremely proud group of teachers. It was one of those things I didn’t really realize at that time and appreciate, but now that I look back the community was really behind the school. They were there when the kids had plays, and there were a lot of those type activities: plays and parties for the kids, and there were field days.

The entire community was always behind those type things; anything that would raise funds for the school, because a lot of the things such as books and even equipment was not given to them simply because the funds were channeled in another direction. Quite often teachers would request new books and not get them, so the community would put on some type of function to get those kinds of things. Invariably, when kids from Douglass Junior High School went to high school, at that time they went to the all-black high school in Brownsville, they were the class leaders. It was really uncanny how it happened so that I think it all started there.

Earl Rice is the son of Tom Rice and former president of the Douglas Community Health and Recreation Council and a science teacher at Haywood County High School. In addition, he is a Democratic National Committeeman and owns and farms land on the Project which earlier belonged to his grandfather.

Earl Rice: The original Douglass School building was torn down in 1977 but stood from 1939 until then. The federal government built it as part of the Project and turned it over to the county. We had an enrollment here at one time of about 600 to 700 students. I can remember this as being probably some of the best days of my life. We used to have plays. I remember I had a starring role in one of the plays which was very fascinating to me at the time. We used to have all kinds of activities during the daytime and nighttime. We would have picnics during the year. We would have May Days where all the black schools in the county would come into the Douglass School. It was an overall competition between all the black schools in the county, elementary schools as well as junior highs.

The teachers here were some of the best that I encountered in my life, and I think that got us off to a good start. They saw the need to instill in us to work hard, to study hard, and that was one of the things that kept us going because during that time it was a crisis situation, days were kinda dark for black people. We had to have that beacon or that light at the end of the tunnel and I think these people provided all of the services that we needed to keep us motivated and moving in the right direction.

The Douglass School today is on the killing floor so to speak. It’s going to be phased out, as it stands. The superintendent of schools has stated that the population shift is to the city and they have plans on the drawing board to build a new junior high school and to add new classrooms on to Haywood Elementary and plans for a new gymnasium at Sonner Hill Elementary and when that occurs, probably within three to five years, Douglass School will be phased out.

Freedom Movement

Jesse Cannon, Jr.: The first year there was freedom of choice, I had the choice of starting as a freshman as a member of the first integrated class at Haywood High School here. I opted to do that with the encouragement of my eighth grade instructor and that was how it all started as far as the integration was concerned. I was a member of the first integrated class and my class was the first to have gone through four years of integrated situation. There were only 15 blacks that first year and the total enrollment was about 800 students.

That experience was one that taught me a lot. It was an atmosphere of hatred. It was almost as if you were living in two different worlds or two different planets, to go to school there. It was very traumatic for some of the children, and they had some long-lasting emotional damage because of it. Somehow, I survived. I started participating in various community activities such as the band and we got into sports, my brother and I. It was not a bad experience by the fourth year, one that I think made me a different person. A lot of things changed because of us and a lot of people probably changed because of us and I’m sure we did, too.

The largest group of blacks at that time [late ’50s] who were leading the Movement were people from this particular community. They were the ones who provided homes for various civil-rights workers or other legal people to have a place to stay. They knew that they could provide those homes without fear that someone was going to kick them out because they were doing that. Not only that, they organized rallies and provided transportation. They did the legwork and they organized the first massive groups to descend upon the courthouse here in Brownsville, the county seat, and they were the ones who stood there in lines for weeks to get registered. They could do this because they had their own farms.

During those years, I remember my parents being very edgy all the time. I know they took turns sitting up at night while sort of standing guard particularly after there had been some bombing incidents in other communities. I remember they organized a community-type guard system and they would take turns watching for any strangers coming through the community.

Tom Sanderlin arrived at the Project within a year or two of its beginning and still lives in the house into which he moved. He was renowned for his cooking both at the August 8 celebrations and at the camp which was conducted for the New Farmers of America.

Tom Sanderlin: The time when we went to register and vote, the white people called it a “thing.” “Ya’ll niggers got that thing going on out there. Ya’ll trying to take the county over.”

I thought that some of the white friends I had were my best friends in the world, but when I got my name on that charter, I speak to them and they’d ask me what could they do to me, not what they could do for me. We’d stand in line to register. They’d put acid on the steps at the courthouse and folks would go up there and sit in it. Some of them old people — when they stand up all their pants be done ate up. But we kept a hanging in. If they just had opened up and say, “All ya’ll niggers come on up here, register and vote,” it wouldn’t been a bit of problem cause they wouldn’t went. But when they find out that they were trying to keep the vote from us, then we went to getting the folks to register and vote. We knowed it was important. You go to the white man’s store, if you hadn’t registered or tried to vote, you’d get what you want. But those trying to register and vote, it was hard for them to get what they wanted. They wouldn’t let em have it. The Negroes that were working for the white citizens, they were told they better not and they wouldn’t.

Tom Rice: We started in ’57. We got to reading different books and reading Dr. Martin Luther King and he explained to us what it takes to make a citizen.

Earl Rice: The [Haywood County Voters] League was set up in order to get the right of blacks to be able to register to vote. Because of the fact that my father was one of the League’s co-founders, it brought on a lot of problems. The business was thriving at the time and during the crisis situation that arose after that my father’s business was totally cut off. He was boycotted. He was refused service by the Coca-Cola company here in Brownsville and the wholesale houses here in Brownsville which used to deliver groceries to him. His credit was cut off at the bank. He was unable to establish good credit. There were other people also who were denied credit, and they had to go into Memphis to establish credit. And through this my father endured tremendous pain. He had to stand by and see his business drop down to nothing and food he had been selling, he could no longer get because of the fact that he was involved in the founding of the League.

Jesse Cannon, Sr.: My boy, the doctor, he was organizing. I can’t remember it now, some type of a club. Anyway, they made him president. He didn’t know what it was all about when it began to develop and come to find out he was the president of this area here of the civil rights. They would go places, I’d take my truck and haul loads of them — white kids, black kids, what not — go to Brownsville, Covington and they demonstrated.

Somehow or another we lost the idea of being afraid of anybody when we realized that it was right for us to have our rights to vote like everybody else. We decided we were going even if we died. One of the officials had some of us fellows that was interested in it to come to his house and talk. He was trying to tell us not to register. We told him that they register dogs, they register old cars, trucks, why couldn’t we be registered?

“Well, it just ain’t time. I don’t want you to be too hasty.”

But we realized that we had waited too long then and we were just determined to go on. We went right on and the Lord blessed us. We come through. No one got hurt. One person got hit there in town. Many a family that was living on the other man’s place had to move, but us, having our own place, we wasn’t threatened. It gave us consolation to know that we could set still and still we could fight for our rights and that’s what we did. I never was threatened directly, but I was afraid in a way, cause I determined if they did come here to kill me I was going to die trying to provide for my family.

The Clinic

Jesse Cannon, Sr.: Sometime in the early ’70s some students from Vanderbilt come down and they was talking to us about a clinic that was being established in Rossville* and telling us what a grand job they was doing. They were trying to get the idea in us whether or not we would like to have one in this community. Finally, they come down and set up a health fair here. I believe it lasted about two weeks. People could go in to be examined, treated and different things. They even carried some to the hospital and directed them to doctors for certain complaints. They had a dentist there who pulled teeth and they helped the people out so much until we just admired it, admired the effort.

Later on they asked, “What do we feel that we need the worst down in this community?” It was suggested that we needed a recreation center and later on it was suggested that we need a clinic.

Earl Rice: Some while back, we dreamed of being able to work to develop a clinic. I feel it would never have happened if it had not been for the health fairs because of the awareness that was rekindled in the minds of the people. They could see how a clinic would really work. I think many of them after the fairs said, “Well, this worked so easy, maybe we can get this accomplished.” People in the community were saying that we’re going to have something close, where we can have medical help. We want a doctor. We have the brain power in the Douglas community to produce a doctor, to produce a lawyer, or anything else we want.

One of the greatest things about the clinic is that I’m a part of it; that I have been able to help and to work as hard as I possibly can to help the people within the community to make this a reality. I think putting these things all together, the clinic, as a whole, is a dream come true and I’m proud of it and the fact that I had a part in it. This is something that I had always dreamed of, being useful, helpful to my community. I had the opportunity to go elsewhere to work, but I chose to come back home and to help out at home.

Jean Thomas Carney is the director of the Douglas Community Health Clinic. She is a native of Haywood County who shared the common experience of migration to another urban area, in her case New York, and the dream of finding a future which was different and better than the past which she knew. After her return to the county, she studied public administration, worked as a child advocate in Haywood County and directed the development efforts of the Douglas Community Health and Recreation Council which sponsored the clinic.

Jean Thomas Camey: I really wonder what the people were doing before, how did they live with some of the problems that they have. They just didn’t have the money for the care or they had medicaid/medicare cards and the physicians are so overbooked in the areas that they take a certain number of medicare patients and no more. Well then, that leaves people having to travel long distances for care or to find someone who would accept the medicare/medicaid card, and if they haven’t got the transportation, they still can’t go and if they hire someone to carry them, it’s going to cost them. This is a poverty area and there’s just no doubt about it, there’s no question about the need here and what the clinic is doing for that need.

Jesse Cannon, Jr.: My becoming a doctor was strictly an impulse. I graduated from high school in ’69. I had already received a scholarship in engineering at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Three days after graduation, my mother died unexpectedly. My response was not so much one of remorse but of anger. I felt that there had been some foul play. My initial impulse was to find out what it was, and I figured the only way I’d ever find out was for me to be a physician. So I promptly called my guidance counselor and told her that I was going to change my major in college, and that’s how it all started.

When I was finishing up, I was looking for some source of funds. I had scholarships and grants in medical school, but I also got married and couldn’t raise a family on those. I needed extra money so I sold my soul to the National Health Service and that’s honest. Then when it came my time to be assigned, this site was becoming available. I started working with the site about six months before I finished my residency trying to get it organized along with the community members here because my father was on the board, and I knew all the people who were working with it. So I just started coming out every so often giving them some pointers about things I thought should be included in the project, and when I asked the regional office if I could be assigned to it, then they said, “Fine.” So here I am.

Jean Thomas Camey: We’re proud of what we’ve done for the town, too. I feel that renovating this building [the clinic] here in Stanton has really brought the town back to life. Down the street there are a number of stores that have opened up; we even have a drug store on the corner that wasn’t here before. Buildings that were torn down, very little activity, there’s much more now as a result of the health clinic being in the town. We have more people coming here for health care, then they use the drug store; they are able to go to the bank and then down to the grocery store. Plus there is a restaurant here now that wasn’t here before. We brought our doctor back. I think it has made a remarkable change in the community.

Jesse Cannon, Jr.: One of our more interesting early experiences was with the mayor of Stanton, who was white, of course. It was an emergency, he had burned his hand cooking something and spilled some grease on it. He come running in the door and asking for help, in obvious pain and with second degree burns on the palm surface of his hand. We took care of it and followed him up for about two weeks, and he got very excellent results without any contractions or any deformity. As a result of it, I think of his telling other white merchants and members of the community, we subsequently got all the white merchants to come here as patients, even one of the local contractors who is a multi-millionaire. So I think that early experience for him probably helped us to bridge the gap. We had no previous white patients and by him coming here on an emergency basis and getting treatment for a burn and getting excellent results, it was sort of a means for us early on having some contact with the rest of the white community.

Earl Rice: The clinic is working probably as well as I’ve seen any integration measure. Our staff is fully integrated. Dr. Cannon is the black physician. We have a white nurse practitioner. So the entire office staff is fully integrated with the front office being black and white. Each time I go into the clinic, I see the chemistry working and coming together so great and the people are working together. If someone had told me this would be going on in Stanton, Tennessee, I would not have believed it. But today it is working.

Jean Thomas Camey: Twenty years ago, I wanted to get away from Haywood County and never come back. When I left Haywood County, I said I would never, never come back. I did come back, not because I wanted to, but because there was illness in my family and I had to come back. But after I got back here, I saw a need and I saw some things that I wanted to do here at home, and I felt that I couldn’t get these things done living someplace else. The only way to get them done was to stay here and work with the people to make these changes.

We’re going to expand the clinic and we’re going to work on our recreation park which we have an application in now to get funds to provide a recreation site. We’re looking at the possibility of providing low-income housing through the Douglas Community Health and Recreation Council. So this council is just a beginning, really we’re just beginning.

The people here are originally from the community and they feel that this is home — “I’m not going anywhere, I’m going to do what I can to improve the community.” They are farmers and they’ve always lived on the land and they feel like this is mine and I’m going to take care of it. Even though it’s been a long time, I know from ’75 to ’79 getting just the clinic opened, they didn’t give up but kept right on going, kept right on trying. I think they will continue the same way and I think the children will carry on. They have a feel for what a grass-roots group can do, what people can do, if they come together and work together and stay together.

Tags

Richard Couto

Richard Couto, Pat Sharkey, Paul Elwood, and Laura Green — all affiliated at the time with the Center for Health Services at Vanderbilt University — conducted an extensive evaluation of RCEC for the U.S. Department of Education in 1986. This article is adapted from that report. (1986)