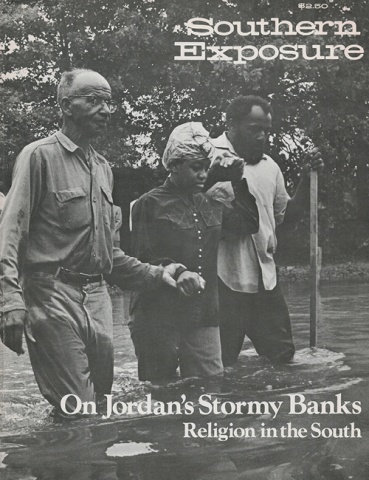

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

This article is the result of many hours of taped conversations and research in the papers of Claude and Joyce Williams at their home in Alabaster, Alabama. All quotations are by Claude Williams, unless otherwise noted. For additional information about the South during the Depression, especially about the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU), readers are encouraged to see Mark Naison’s excellent article on the Williams published in the “No More Moanin’’ issue of Southern Exposure (Winter, 1974).

As we were going to press, we learned that Joyce Williams, in her 80’s, had just died in Birmingham, Alabama. We extend to Claude our warmest regards and salute Joyce for her untiring commitment to the struggle for justice and equality.

"Is not this the carpenter, the son of Joseph?” Well, if he was a carpenter, he knew what it was to have horny hands and patched clothing. Because you couldn’t do the kind of work he was, felling trees and dragging them to the house to make ox yokes and carts, without tearing your trousers. He was a carpenter. He knew what it was to work long hours with little pay. He was born and reared in a worker’s home. He knew what it was to dwell in a shack, because carpenters even today don’t build mansions for themselves but for other people!”

That’s the voice of Rev. Claude Williams, speaking much as he did 35 years ago to groups of sharecroppers in the Arkansas Delta and shopworkers in the war defense plants of Detroit. Standing now in the close quarters of his Alabama trailer-home office, the preacher’s voice rings as it did those many years ago, when conferences of workaday preachers and Sunday school teachers would meet for days in churches and union halls to consider the Biblical teaching: “the meek will inherit the earth when they become sassy enough to take it!’’

Hanging on the wall before him is one of Claude’s unique visual education charts. It is a large affair, three by four feet in dimension. At the top, it bears the legend, “The Galilean and the Common People.” In circles and rectangles covering the chart is a succession of modern, simple drawings, each depicting scenes from the life of the Son of Man.

Waving his homemade coat-hanger pointer at the chart, Claude refers to each drawing in turn as he recounts how Moses called the first strike down in Egypt, how Jeremiah spoke out fearlessly in the name of true religion against the rulers and priests of ancient Israel, and how the Son of Man was reared in this tradition by a poor family who belonged to a movement seeking to bring about the Kingdom of God in their own time and place.

This is the kind of talk that went on in the People’s Institute of Applied Religion (PIAR), surely one of the most remarkable expressions of religion ever to appear in the South. The PIAR was created in 1940 as an independent means of training the grassroots religious leaders of the cotton belt in the principles of labor unionism. For its principal founders, Claude and Joyce Williams, it represented the unique melding of religious and political convictions that had grown in them over a long period.

I

Claude and Joyce Williams came by their religion honestly. Both were born into fundamentalist homes, Joyce to a farming family in Missouri and Claude to tenant farmers in West Tennessee. They met and married in the early 1920s at Bethel College, a conservative Tennessee seminary of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. But their re-ligious views gradually began to change as they pastored their first Presbyterian charge near Nashville. Partly, as in the case of their increasing unease with racial segregation, the change was based on seeing the contradictions in their culture between Biblical teaching about justice and actual social practice. At the same time, avid reading led them to discover the refreshing vitality of modern religious social thought represented in Harry Emerson Fosdick’s The Modern Use of the Bible.

The turning point came in 1927 when Claude enrolled in a series of summer seminars at Vanderbilt University taught by Dr. Alva W. Taylor, a Southerner, member of the Socialist Party and prominent exponent of the social gospel. He recalls that Taylor “had a way of removing the theological debris from the Son of Man under which he’s been buried for all these centuries and making him appear human.” Claude found it impossible, after this experience, to continue working in a conventional church ministry.

In 1930, the Williams moved to Paris, Arkansas, to serve a small Presbyterian mission church. Located in the center of the state’s mining district, Paris offered more opportunities to practice their new religious ideas than they could have ever imagined. Their first real working acquaintance with political action came with their involvement in the miners’ efforts to organize a union and join the UMWA. With characteristic energy, they opened the church, their home and their family life to this movement. They participated in strategy discussions, helped raise money, and Claude wrote many of the necessary documents and position papers. Their participation clearly grew out of their religion, and they learned that the warm response of the miners and their families was due, in part, to their interpretation that the union fight was completely consistent with Biblical teaching.

The Williams also began in Paris a program of study and learning that became a cornerstone of their long ministry. The Sunday evening “Philosopher’s Club,” held in their home, was a regular feature of church life. These meetings involved open and wide-ranging discussion of religion as well as the multitude of political and cultural ideas sweeping the country during these Depression years. They encouraged the young people to read, opening their own library for use at the church. Moreover, Claude was much in demand as a speaker throughout the coal fields. He traveled thousands of miles, addressing meetings of miners on behalf of the union, and from these contacts, “socio-Christian forums” grew in several west Arkansas towns. Through all these experiences, Claude was developing his own way of preachingIteaching, emphasizing exhortation and emotion, but likewise encouraging objective analysis and collective action.

Chiefly because of the Williams’ work with the miners and the young people of Paris, the church elders eventually brought successful action within the presbytery to have Claude removed from the pulpit. In 1935, they were forced to move to nearby Fort Smith. They quickly became active with the organization of unemployed workers, and Claude was jailed for three months for participating in a demonstration. They moved again, this time to the relative safety of Little Rock, and were soon giving full time to workers’ education and organizing with one of the most significant political movements to sweep the Depression South - the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU).

By this time, having endured many difficult experiences and met a number of Marxist activists along the way, their political and religious views had become more radical. Likewise, their views about taking seriously the people’s religion were taking concrete form.

They knew from their own backgrounds that working with poor people in the South, both black and white, meant working with people whose view of the world was strongly conditioned by religion. Everything that it means to be good, to live honorably, to find support through life’s trials and hope in the future — these are the profound personal and social questions that poor Southerners have answered in religious ways for generations. The Bible is the book that points the way. For many, it was the only book they ever read. The church was the strongest institution in their lives; unlike most other things in life, it was theirs. It was a place where their own forms of community relationships took shape and where their own leaders found legitimacy. The Williams knew well the other-worldly and apolitical dynamics of this religion, but they also learned from experience how important it was to relate to church leaders if the union was to succeed.

“As we spoke with the sharecroppers, we were obliged to meet in churches, both black and white. Most of the churches we met in, of course, were black churches. And it developed, especially with the black churches, that the pastor usually was present and chaired the meetings. Unless he said ‘Amen’ with that certain inflection which got the people to saying ‘Amen’ and rumbling their feet, we might as well go home.”

The first big opportunity to test this view came in 1936 when a number of radical organizations in Little Rock, recognizing Claude’s organizing ability, encouraged him to set up a school to train grassroots organizers for the STFU. In essential ways, the New Era School of Social Action and Prophetic Religion prefigured the People’s Institute.

“In December, 1936, we held this first school for the sharecroppers. Nine whites and ten blacks. J. R. Butler (president of the STFU) got the students and I raised the funds. I wrote J.R. Butler from New York that we were gonna have the best school ever conducted in that land of ours ‘South of God, decency and democracy. ’ Well, we did.

“We went through every phase of union organizing. It was a ten day school, night and day, solid. We didn’t have any charts then, but we discussed the union problems. Then we’d assign someone to go down and organize the people in this county, or this neighborhood. Well, they’d have to study that and then make speeches as though these people were the local people. Then, after we’d done that, we had them go through organizing, setting up a local. Then we went into negotiation, getting a contract. The next to the last night, we had a group of Workers’ Alliance people come into the meeting as planters with dubs to break it up. And it was so realistic. One very dynamic woman, whether it was spontaneous to the occasion or whether she just sensed, she jumped right out in the middle of the floor and began to sing: ‘We shall not, we shall not be moved. We shall not, we shall not be moved.’ . . . Well, they came around. ”

For the next three years, the Williams were deeply involved in STFU activity. Claude was one of the union’s most skillful organizers and a member of the governing board. In 1938, when he became director of Arkansas’ famous labor school, Commonwealth College, he made his work with the sharecroppers the field program of the institution. When sectarian conflict within the union’s leadership led to his expulsion from the STFU board and his subsequent resignation from Commonwealth, it was natural that Claude would turn to what he did best. The People’s Institute of Applied Religion became the vehicle which made use of the Williams’ experience in religious workers’ education.

II

By the time the PIAR came into being, the Williams had refined their approach into a more conscious and systematic religious form. The purpose was to work with the natural leadership of the South’s poor, always in an interracial setting; to engage them on their own terms, in light of their own experience and their own religious world view; to translate their religious perspective into the need for collective struggle for economic justice; and to develop concrete leadership skills in union organizing. The work was always done on behalf of existing labor organizations.

The three to ten day institute was the chief form of the PIAR’s work. Roughly fifty people, equally divided between black and white, men and women, worked through morning, afternoon and evening in intense sessions. “These were people who had some tendency toward leadership,” recalls Claude. “They were preachers or preacherettes or Sunday School superintendents or Sunday School teachers.” Following the custom among rural churches, each participant often represented a number of communities; at one institute in Evansville, over one hundred churches were represented.

The interracial nature of the institutes was a matter of principle and, in itself, constituted one of the most significant parts of the experience.

“It was the first time some of them had ever been together in a meeting. Most, if not all of them, had never sat down to a meal together, and most of them thought they never would — especially the whites. The blacks never thought they’d have the opportunity. A black man got up and wept and talked when Winifred Chappell called him ‘brother. ’ He never thought he’d ever live to see the day when a white woman said ‘brother’ to him. ”

Even though they depended a great deal on spontaneity and inspiration, the meetings were carefully structured around the people’s religious mindset and how it might be approached.

“We were realistic, or we tried to be. We discovered that the fact that the people believed the Bible literally could be used to an advantage. For instance, if we read a passage from the Book which related to some issue of which they were aware, although it contradicted what they had interpreted some other passage to mean, they had to also include this. Being so-called fundamentalists, accepting the Bible verbatim, had nothing whatever to do with the person’s understanding of the issues that related to bread and meat, raiment, shelter, jobs and civil liberties. Therefore, our approach was not an attempt to supplant their present mindset, but to supplement it with a more horizontal frame of reference. And we found that supplementing and supplanting turned out to be one and the same thing.

“We learned we had to contact these people at their consciousness of their need. We recognized that what the social scientist or the social worker saw as the need of the people and what the victim felt were two entirely different things. ”

Meetings always opened with a song, scripture and prayer, a ritual still practiced in many grassroots political meetings throughout the South. Then:

“When we had them together at the opening session, we would say, ‘Now, we have come here to talk about our problems, the problems we meet every day of our lives. We want to start and let everyone tell she meets, as it relates to food and clothes and shelter and health and freedom.’

“Well, as long as this person would talk, we’d let him talk. If it took an entire day, we let everyone talk. Well, they were ready to talk, you know, after it got started, talking about the things that was dose to them. With the result, after these meetings, they would sit down that evening to a meal together. And I never heard a murmur, they felt such a oneness.”

Following these sharing sessions, either Claude or another workshop leader would begin with the first orientation chart. Claude realized that much of the written material distributed by political organizations was totally inappropriate for the sharecroppers. Those who could read were not prepared to wade through the typical political tract. They needed something visual, something more symbolic than literal, something that would suggest concepts based on the story people were already familiar with—the Bible. So shortly before he left Commonwealth, Claude worked out four basic charts for orienting people to the “positive content” of the gospel. A young artist at Commonwealth named Dan Genin made the drawings.

These charts were used throughout the history of the PIAR, and include “The Galilean and the Common People.” Another, called “Religion and the Common People,” recounts the origins of religion in superstition, the ways religion has been used by rulers to subject people, and the emergence of people’s religion in the Old Testament. A third, entitled “Religion and Progress,” illustrates how civil values like equality, freedom and justice support true democracy. A fourth chart, “Anti-Semitism, Racism and Democracy,” counters the evils used during the Depression and World War II to create disunity among working people.

Over the years Claude introduced other charts, more diagrammatic than pictoral, but still employing the same simplicity. One, entitled “The New Earth,” employs the equation FAITH + VICTORY - WORLD = RIGHTEOUSNESS (WORLD refers to “the present world system”). Another chart, called “Anti-Christs” deals with the forces of evil in the world, especially the Ku Klux Klan. Through these almost simplistic devices, Biblical concepts were translated into contemporary content and people were drawn into the learning process.

Usually, each session dealt with one chart, sometimes only sections of a chart, depending on what participants expressed as pressing needs and problems. The presentations were delivered in sermon fashion, full of the emotion and speaking style which people expected from somebody who had a deep conviction to impart. It was through the charts, more than anything else in the institutes, that the supplementing, supplanting process took place, for what people heard were the old familiar events from the Bible, buttressed by chapter and verse, but told in a way they never expected. They exclaimed, “We never heard it on this order!” and at the same time they said, “It makes sense to our minds.”

The same spirit of involvement marked other sessions where participants used mimeographed worksheets to study particular problems such as peonage on the plantations, the poll tax and the lack of educational opportunities. Music also played an important part in the Institute’s, as it did in the participants’ churches. Not surprisingly, singing became part of the learning experience. In fact, out of the institutes (and the previous training schools in Arkansas) came some of today’s best known freedom songs.

“One time in this ten day meeting in Memphis, about the third morning someone began to sing:

What is that I see yonder coming,

What is that I see yonder coming,

What is that I see yonder coming,

Get on board, get on board!

As she sung that through, the way she sung it, I could hear the drums of Africa! I said, my God, we’ve got to do something with that song. When she had finished, I got up. I referred to the songs we had sung in Arkansas. There’s always one verse in the songs that’s related to the people. Like (singing):

I’m going down to the river of Jordan

I’m going down to the river of Jordan one of these days, hallelujah!

I’m going to walk on the freedom highway. . . .

I’m going to eat at the welcome table. . . .

Well, we changed the I ’ to 'we ’ and we sang:

We ’re going to walk on the people’s highway....

Well, when I sat back down there in Memphis, this woman got up and began in the same deliberate cadence:

What is that I see yonder coming,

What is that I see yonder coming,

What is that I see yonder coming,

CIO,CIO!

It is one great big union,

It is one great big union,

It is one great big union. . . .

“It has freed many a thousand. . . .

Well, I went to New York and went to Lee Hayes, Pete Seeger and Millard Lampell and the Almanack Singers. I repeated this and told them what happened. They took it to Paul Robeson. Paul Robeson said, “That's our song. We've got to use it. That’s the basis of ‘The Union Train, ’ been sung now around the world. And Miss Hattie Walls must be given credit for it. She’s the one who first sang it. ”

The last hour of the institute was something like a praise meeting, full of singing and prayer and testimony about what the experience had meant to people.

“We thank you, for we are beginning to see the light.”

“Where there’s hate, there’s separation; where there’s separation, there’s weakness. Let’s stand together.”

“Jesus meant for us to have economic freedom. Let’s not expect God to fill our mouths when we open them.”

“We want to thank you for the things we heard that we did not know. We thank Thee for unity. Break down every wall of partition. We pray for those in distress in body and mind. We realize Thy will can be done only in our bodies. Heavenly Father, take charge of every one of us. ”

Then they went home to organize the union.

III

In its initial years, the Institute worked closely with the sharecropper movement and developing CIO activities in the South. A PIAR report for the fall of 1941 describes a number of institutes held in cotton belt places like the Missco, Arkansas, federal farm; Longview, Texas; Hayti, Missouri; Osceola and Carson Lake, Arkansas. The meetings encountered increasing harassment and threats of violence from local planters, law enforcement officials and hired thugs.

At the Missco institute, fifty vigilantes appeared, and the leadership could not leave the project for fear of their lives. Because of the intimidation, several institutes were held on the periphery of the cotton belt where sharecroppers could be transported away from terror. In March, 1941, some fifty cotton belt church folks gathered in Evansville, Indiana, for an institute, and in late April another was conducted in St. Louis.

The work of arranging these institutes was carried out by the Williams and a band of colleagues who joined the Institute soon after its formation. Some were cotton field preachers who had worked with the STFU and remained active after the union joined the CIO’s United Cannery, Agricultural, Packinghouse and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA). Chief among them was Rev. Owen H. Whitfield, a black Missouri preacher, one of the strongest leaders to emerge from the sharecropper movement. Whitfield was a co-director of PIAR, and he and his wife Zella participated in many institutes. Other friends from STFU days took state responsibilities, including Rev. W.L. Blackstone in Missouri and Leon Turner in Arkansas. Claude’s brother Dan, himself a preacher and sharecropper, was active in Missouri and helped arrange an institute in that state which was broken up by planters.

One of the Institute’s most amazing recruits was the Rev. A.L. Campbell, a white preacher from Arkansas. Campbell worked on the 60,000-acre Lee Wilson plantation and attended the Evansville institute as a spy for the Ku Klux Klan. But the message he heard, particularly the frontal assault on Ku Kluxism, “converted” him, and thereafter he was one of the Institute’s most single-minded and effective leaders.

Others helped. Don West, who had studied with Claude under Alva Taylor at Vanderbilt, took responsibility for Georgia. Harry and Grace Koger were also deeply involved. Harry, a former YMCA executive, was the regional organizer for UCAPAWA in Memphis. And Winifred Chappell, a co-worker with Dr. Harry F. Ward in the Methodist Federation for Social Action, was a co-founder and co-director of PIAR. She had been a prominent supporter of the textile strike in Gastonia, N.C., in 1929, and worked with Claude and Joyce in Paris, Little Rock, and later in Detroit.

These people formed a network throughout the South, continually traveling, speaking, organizing meetings, corresponding, leading and recruiting people for the union and the institutes. Each was trained in the institute methodology and the use of the charts; each brought to the task their own distinctive personalities and interpretations.

They were supported by a network of PIAR chapters and friends in northern urban centers, including many well-known progressives from labor and civil-rights organizations, along with professionals from religion, education, medicine and even a few businessmen. Claude, Winifred Chappell and others established and sustained these committees through frequent travel. The network provided the financial support necessary for the work in the South. For Claude and Joyce and the others working in the nation’s poorest region, eating was always a catch-as-catch-can proposition. Their ability to stay alive and to underwrite the Institute’s activities depended in large measure on outside support. So, at certain times, did their legitimacy and their safety. More than once these groups came to the aid of people, including PIAR staff, who were in jail or under threat of terror.

In the summer of 1941, the PIAR conducted its most controversial, dangerous and significant meeting in the South. At the time, Memphis was one of the most brutal urban strongholds in America, totally controlled by the violent and racist machine of Boss Ed Crump. When the CIO began to organize in Memphis, Don Henderson of UCAPAWA asked Claude and the Institute to hold a labor school, cautioning that he didn’t want “any of that new wine in old bottles stuff.” Claude and Joyce, the Rogers and Owen Whitfield, ignoring that instruction, used the charts in all classes, and Whitfield and Koger used them quietly at union meetings. Their work culminated in a ten-day institute that included packinghouse workers from Memphis and sharecroppers from as far away as Texas.

The conference was one of the most spirited and thorough ever conducted by the Institute, and it had more far-reaching effects. Memphis’ considerable repressive establishment had been conducting a terror campaign against the CIO for months, and when word of the institute hit the newspapers, the forces of reaction struck swiftly. Harry Koger was jailed for questioning and a few days later Claude was taken to police headquarters and interrogated for two days. The “big union” had come to stay, however. Within months the CIO had dug a foothold into several Memphis industries and within a few years the Crump machine itself would fall. Encouraged to leave town for their own safety, Claude and Joyce once again moved the family and PIAR headquarters, this time to Evansville, Indiana.

During the war years, the Institute remained active throughout the cotton belt. The Williams did not stay in Evansville long, for in early 1942, Claude accepted the invitation of the Presbyterian churches in Detroit to establish a labor ministry there. Detroit was the center of national war production, and new migrants were streaming into the city from the South at an unprecedented rate. Racial tensions ran high, encouraged by an army of reactionary religious demagogues like Gerald L.K. Smith, Father Coughlin and J. Frank Norris. Aided financially by the lords of industry, these “apostles of hatred” preached a divisive message of racial purity and antiunionism quite familiar to the Williams from their years in the South.

The program they established represented the continuation of the PIAR. With the cooperation of the new United Auto Workers, shop committees of working preachers were set up to use the charts and preach “realistic religion” in the plants at lunchtime. An interracial “Brotherhood Squadron” of speakers and singers appeared in churches. In 1943, Claude authored a scathing expose of the right-wing religious leaders; and Philip Adler, reporter for the Detroit News, wrote a series of favorable articles on Claude based on the report. Liberal church forces, along with other professional and civil-rights organizations, were enlisted to help combat the tremendous forces of reaction in the city, and the PIAR leadership played a crucial role in negotiations to end Detroit’s second major war-time race riot in June, 1943.

As the war ended, the churches who sponsored the Williams’ work bowed to the concerted counterattack on Claude by Smith, Norris, Carl McIntyre, and the House Un-American Activities Committee. Charges of heresy were brought against a Presbyterian minister for the first time in over one hundred years. (The inevitable guilty verdict came down in 1954.) The PIAR continued for several more years, but like all progressive forces during the McCarthy years, found the going rough. In a ceremony at St. Paul’s Chapel in Brooklyn on July 20, 1948, the PIAR brought its formal history to a close, all members vowing to continue as volunteers of the Way of Righteousness.

IV

Underlying and informing the Williams’ work throughout the years has been a concept of religion which, at the least, is out of the ordinary. Those who came in contact with the People’s Institute of Applied Religion heard its application to the problems of their own time and place. Only a few are familiar with its basic assumptions and the great detail in which the Biblical story is spelled out. There is space here only to indicate its outlines.

There are several things that religion is not. It is not a belief in anything supernatural. It is not a belief in a divine force outside human life which directs events. Assuredly, it is not the church or the practice of any organized religion. Nor is it theology, an intellectual discipline which assumes a fundamental distance between God and people. Rather, Biblical religion is a way of comprehending reality that “deals solely with the intangible facts of existence and communicates these facts by a symbolic language, by legend, by myth, miracle, parable and allegory.” Religion does not pretend to be science or history. But it does insist that the intangible facts of existence are as real as the tangible, and that the intangible, in fact, gives “warmth and feeling and meaning” to the objective world.

Certain key words are important for understanding the nature of the intangible. One is the word “qualitative,” which implies that the nature of reality is personal, that it has to do essentially with human beings and their welfare.

“I believe God is a symbol of the qualitative unity of reality. I don’t believe God is a person like we think of a person. But I think personality, communication, thought, things like that are inherent in the universe. I don’t believe I'm alone. I believe there is a qualitative essence in the universe of which I am an integral part, and to which I must be loyal to attain my greatest potential. So, I am religious, but I don’t believe in supernaturalism as such. ”

Another descriptive word is “comprehensive.” All things are one; life is not defined by any dualism, Greek or otherwise. The physical, rational and emotional in people are distinct from one another, but they are not separate. They comprise a totality, and to treat people as though they can be fragmented into parts violates the intangible reality of life.

Likewise, people are not separate from one another. They are not isolated individuals but social beings who are inevitably bound to one another. They do not live in a world where the spiritual and the material are separate. The intangible meanings of life are to be found here and now, in our daily activity. The Kingdom of God is a goal to be achieved continually in this world. It is a collective struggle for the good, which is itself comprehensive. The good implies living and working together in a society where everyone has food and clothing and shelter, where everyone is encouraged to learn and imagine and create, and where people care for the natural world around them. For the good to be realized, belief and action can not be separated. In the words of the Son of Man, “Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ shall enter the kingdom of heaven, but he who does the will of my Father who is in heaven” (Matt. 7:21).

The source of this understanding is the Bible. Of course, the way Claude and Joyce understand the Bible has changed a great deal over the years. During the 1930s, a friend gave Claude a copy of Lenin's State and Revolution, and he declared it ‘‘the most revealing commentary on the Bible I had ever seen.” As he pondered how the Bible would read in light of this new perspective, he tried an experiment which he later described in a 1947 publication of the PIAR entitled Religion: Barrier or Bridge to a People’s World:

“In order to bring out in bold relief the class tines of the Bible, take the following simple steps. Write down what any intelligent person knows — that the issues of today demand racial, economic and political justice for all people. Then take the Bible and underline with a red pencil all passages which support these ends. With a black pencil, mark the passages which defeat these ends, by escapism or confusion.

“The simplest reader will see Abraham, Moses, the prophets, John the Baptist, the Nazarene, Peter, Stephen, James and others as leaders of the people and at one with them in their fight. He will see Ahab, Jezebel and other robber-murderers; Pharoah with his taskmasters, magicians and soothsayers; the landlords with their winter and summer houses; church religion with its false prophets, high priests, priests of the second order; the Baals, Caesars, Herods and Pilates — all these as spoilers of unity, oppressors of the people and enemies of justice.

“Here is the foundation of a people’s interpretation of the Bible.”

Over the years, this ‘‘people’s interpretation of the Bible” has crystallized into a systematic account of a people’s movement that Claude calls ‘‘The Way of Righteousness.” It is the story of a self-conscious movement of poor and oppressed people beginning with Abraham, a movement that waxed and waned on the basis of political circumstances throughout Old Testament times and always couched its class dynamic in religious terms. Its contours first take dramatic form in the Exodus, when a number of Semitic tribes enslaved by the pharoahs of Egypt unite and rebel. It continues through the time of the kings of Israel, when a prophetic opposition — personified in Amos, Hosea, Jeremiah and Isaiah — protests the oppression of the common people by Israel’s corrupt rulers, enduring death and persecution for its efforts. It traces the beginnings of class internationalism in the writings of Isaiah, Elisha and Elijah, and in the story of Jonah.

Then, the account relates how the Way, which for many years after the Prophets had existed underground, goes public again when Rome unites the world’s poor in a common condition by declaring a universal tax. Spoken for by the Son of Man and John the Baptist, who were born into families of the Way and trained for leadership, the movement becomes so successful that John is beheaded and the Son of Man barely escapes execution.

After resurfacing at Pentecost under the leadership of Peter and James, the movement prospers and spreads throughout the Roman Empire, despite the efforts of the Pharisee Paul to deflect its revolutionary content into an other-worldly theological individualism which is always deferential to the Roman establishment. Finally, the movement becomes so serious that, three hundred years after the Son of Man, the emperor Constantine becomes a Christian himself, thereby absorbing the movement into the Roman establishment and leaving it for a much later day for the spirit of the Way of Righteousness to re-emerge.

The methods of the underground are drawn in great detail. All activities of the Way are collective. Thus, while Moses or Jeremiah or the Son of Man or Peter may appear in the scripture as spokesmen, behind them is an organized movement working in intricate ways to carry out its goals. The “multitudes” who gather to hear the Son of Man do not appear magically but are the product of hard organizational work.

The Way is shrewd enough to cultivate friends in strategic high places, such as Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the ruling Jewish Sanhedrin, and the several centurions of the Roman occupying army mentioned in the New Testament. The Way is organized secretly, as would be necessary for any underground movement, and is required to speak in indirect and symbolic language. Thus, “houses” (e.g. Mary and Martha) are centers of underground activity and entrance is gained only by password; “angels” are underground messengers; the “wilderness” usually refers to conferences of the underground, where strategies are considered and decided; and “cleansing unclean spirits” actually refers to encounters with people who are dissuaded from liberal reform, nationalism, adventuristic violence and other prevalent ideologies among those who imperfectly oppose Rome.

Those familiar with the “theology of liberation” are aware that the “Way of Righteousness” closely resembles several contemporary theologies which also identify the struggle of poor against rich as the basic theme of the Bible. Unlike some, the Way is not a document written by a professional theologian and published for discussion in the seminaries. Like others, it is something that must be done. And true to its own perspective, it bears the marks of a particular historical experience.

The work of the People’s Institute of Applied Religion was based on the important notion that political movements need to meet people with an openness to the positive convictions and yearnings they express within their own frame of reference. The PIAR began by taking this approach to the religious rural poor of the South. In the interaction the Institute learned some important things about the people and their religion, and in its own unique way the Institute offered these lessons to the broader radical movement of the time.

From the whites, they learned that otherworldliness and fierce moralism are essentially a protest against, an escape from, conditions which starve and torment and rob people who have no effective way to resist. From black people, they learned that religion is all these things and more. It is also a way of looking at the world which embraces life’s misery yet finds joy in the present and hope in 'the future, and which is willing to move politically when the realistic opportunity arises. The willingness of both groups to join an interracial movement for economic justice under the most threatening conditions, and to do so within their religious faith, gave witness to the Institute’s perceptiveness. It was these people, hundreds of poor black and white believers, who joined with the Williams and the PIAR to write a new chapter in the “Way of Righteousness.”