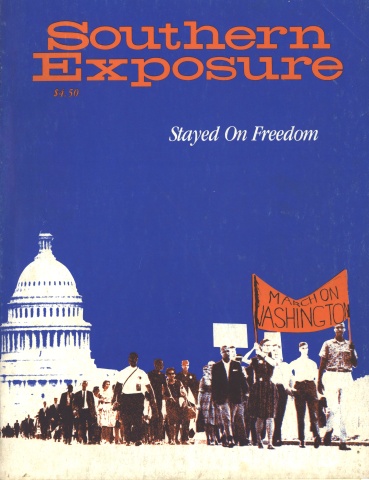

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

James Orange symbolizes the best of the Movement, and is proof that it lives on today. “I was a nobody before I got involved,” he says. “A lot of people could say that, but I know it’s true for me. ”

At 20, Orange lost his job in his hometown of Birmingham after his white boss saw him on television with other demonstrators, challenging the authority of Bull Connor and his police dogs. James soon found himself immersed in the Birmingham Movement and thereafter be became captured by its vision of love, hope and struggle.

He now shares that vision and his powerful energies with a vast network of friends, contacts and fellow ‘‘unsung heroes of the Movement” who are spread across the country, in small towns and big cities where he led marches, took beatings, sang freedom songs and went to jail.

This interview by Bob Hall was taped in January, 1981, in sessions sandwiched between Orange’s annual organizing duties as march coordinator for the Martin Luther King Birthday celebration in Atlanta. We began in a furniture-less apartment converted to his temporary headquarters. In between frequent telephone calls and passing out assignments to a small squad of volunteers, James told his story. ‘‘Hey, ” he said at one point, “this is something I never did before! We got to get more folks doing this. There are so many people, man, who really made the Movement who never get heard from. ”

I give Reverend Charles Billups credit for my getting involved in the Civil Rights Movement. He was an insurance man that worked our neighborhood. But in 1963, the Birmingham Movement began — they was marching and protesting around town — and Reverend Billups was a leader in that. The Klan caught him getting off work one night and beat him up, tied him to a tree and left him for dead. And about three or four days later he was back on the streets, selling insurance and trying to get people to come to the mass meeting. He just told me, he said,' “We got this little preacher from Montgomery, Martin Luther King, and we should come out and hear him.” So I said, “They’re nonviolent, and I’m not nonviolent, so I don’t need to waste the time going down.”

I was one of the young folks in Birmingham at that time that had a little influence with other young people in my community, through the church — I was raised in a Holiness church - and through football. I played ball all through school, and I went off and tried to play pro football, man. I went to a farm team with the Detroit Lions, but got injured and came home. So I was sort of known around by other young people.

Reverend Billups wanted me to get more involved, so I did go to that mass meeting at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Ralph Abernathy got up and started speaking. I guess his speech was the thing that really touched me, that made me want to get involved. He talked about how the police had the church bugged and acted like there was a little bitty bug on the podium. There were two of them police, sitting in the back of the church because they came to all the mass meetings. Ralph was telling the police and the power structure in Birmingham what we was gonna do.

And I said, “Now this dude’s got to be crazy, or either he’s bad.” He was leaning down over the podium, talking to the doo-hickey, saying, “Tell Bull Connor we’re coming. We gonna march tomorrow, get your dogs, get your water trucks, but we’re coming.”

Now usually when somebody’s gonna go out and do something, they don’t tell them they’re coming; they just sneak up on it. But these cats, they announced it. They walked up to the same folk that kids I knew had been running from — I’m talking about the Birmingham police — and just treated them as if they didn’t exist. They didn’t care about getting arrested, about getting beat up or whatever. So I was puzzled, you know, for a long time.

When I first got involved, man, I was chasing a couple of sisters, and they used to be around the church every day. So my mind was really on a lot of different things. The first time I got arrested at one of the marches downtown, I got arrested because the lady that I was supposed to have been trying to hang out with had got arrested.

I kept going to the mass meetings, and I would always talk. I got fired up one day, in the basement of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and got to talking. They were saying that they were having problems with the schools. I said, “Hell, you want the schools turned out, I’ll turn em out!” And they said, “Okay, go do it.” And, hey, I didn’t know how to turn those schools out, but I had got my foot in it. That’s when we got out and started turning out schools.

That was a part of SCLC’s thing, to turn out schools. After I joined the staff, we probably turned out, in communities, a good 50 to 75 schools across the Southeast. We’d go directly to the students, completely close the schools up, shut them down. Those students were our troops because the parents were working. They couldn’t go and march. And if they marched, they’d lose their jobs. But there was nothing for the kids to lose. That was the way we did it.

You talk to the students about being able to go into a restaurant or go into a department store and buy goods but yet they couldn’t sit down at the lunch counter. You talk to the students about being able to go into the courthouse and have to see a fountain say “colored” and another fountain saying “white.” And you had to get that fear out of their heads, and once you erased that, then we would march.

So they put me in charge of the students in Birmingham. They gave me Ensley, Fairfield and Powderly — those were three communities in Birmingham — and said that whatever you can do to turn those schools out, do it. I attended Parker High School and I told them that I knew more people at Parker than I did at those other schools. They said Parker students just wouldn’t turn out because it’s a middle-class high school.

So we went down to the school, to one of the classrooms, and asked them, “Y’all wanna go march?” They said, “Yeah.” And so we started walking out in the hall, singing. And we got on out and by the time we got to the door, the whole school was behind us. We marched down Eighth Avenue, down towards Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Reverend Bevel and Andy Young and all of them, when they saw the students coming, they didn’t know what to think, because that was really the largest group that they had had downtown. Some clergymen and some more adults had already been arrested that day.

When we got those kids downtown, we went to Fairfield and turned out a couple of schools in Fairfield, and on our way back we didn’t have any transportation, so I had about 20 people in a Rambler. They was on the hood, on the top of the car and inside the car. The police in Fairfield stopped the car, and arrested me for driving a vehicle with too many people, inciting a riot and contributing to the delinquency of a minor. And they put me in jail. I stayed in jail for about 10 days, and that was the second time that I’d been arrested, so I really was afraid. I didn’t know what was going to happen. It was about three or four days before anybody found out where I was.

When they finally got me out of jail, they just gave me an area and told me to organize it. And that was Powderly, and in the Powderly community we registered I guess about three-fourths of the people to vote.

One Sunday, Dr. King said that we was gonna have a march. I really wasn’t committed to nonviolence, you know, but there was a little girl — I guess she was about four or five years old — in the park when the police and firemen were shooting the water. She had lost her parents and was there by herself. She walked past one of the dogs, and I just picked her up, and she said, “I wanna feed em, I wanna feed em.”

I didn’t know what she was saying, but Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth heard what she had cried. He got in the church that night and said James Orange was carrying this little kid, and the only thing the little kid was saying was she wanted freedom, she wanted freedom. He said, “The babies are even talking about they want freedom.” And I guess that incident sorta pushed me out front in Birmingham. And I was put on staff at $5 a week.

Fred Shuttlesworth was the main leader — we only had one in Birmingham. Shuttlesworth had more staff folk at the Alabama Christian Movement Association, which were volunteers, than King had on the national staff of SCLC. We had a larger movement in Birmingham than there was with the Montgomery Bus Boycott. But see, the publicity went to King, it didn’t come to Fred Shuttlesworth, who was out there years before Dr. King got out.

SCLC was also involved then in Gadsden, Alabama. We were running two movements simultaneously — Birmingham and Gadsden — when I started on the staff. I pulled into Gadsden once. I had Marlon Brando, Tony Franciosa and Paul Newman in a van, and the highway patrol saw me taking them to speak at a mass meeting. Entertainers had gotten involved, really involved, at that time. I left them in Gadsden, went back to Birmingham, and the next morning, they said that they wanted me to go back to Gadsden and help them with the demonstration. But when I got to Gadsden, I was arrested immediately. They told me I was Meatball, and I said I’m not Meatball. (Meatball was a brother from Birmingham who was really the student leader that SCLC had sort of keyed in on.) And when they arrested me, they put me on the elevator and beat the devil out of me, from the first floor to the second floor. I took a lot of beatings in those days.

When I left Gadsden, they sent me to Danville, Virginia, and then to Texas. This was 1963. We were able to help get over 280,000 people registered to vote working with the Texas Coalition. Senator Ralph Yarborough was working with the Coalition then; it was made up of labor groups, church groups, black civil-rights groups, Chicanos and poor whites. And that coalition convinced Dr. King to send us to Texas to help. We really went tosing, to teach them freedom songs — Andrew Marisette, Liz Hayes, Robert Seals and myself. They gave us this white van, the same van that we had went to Gadsden in. I spent seven months in Texas, and that’s really when I got back into the groove of trying to deal with education and pulling people from low-income communities into the whole concept of really going a lot further into education.

When I went back to Montgomery, I was immediately assigned to Jim Bevel. That’s where I learned and started my teaching on nonviolence. A lot of people talk about the influence of Dr. King, but I speak about Bevel. He was my teacher. He was one of the key people that Doc attracted, one of the young ministers who chose not to be in a parish but who chose to make the Fifth Chapter of John become a reality — making your word become flesh, taking up thy bed and walking and going under His name. That was part of my life, and I don’t know what I would have done or where I’d be without it. That was what we learned, man, to love — how to love thy enemy.

So, beginning in ’64, I was a part of the Bevel staff. We worked in Montgomery and in the St. Augustine, Florida, Movement during the same time. They were in St. Augustine talking about the right to swim. And we spent the spring and summer of ’64 in Montgomery protesting, getting people registered to vote, getting people to go into the public school system. That was the year that blacks integrated the schools in Montgomery.

We had heard that SNCC was down - in Selma and that no more than two blacks could walk up and down the street together. If more than two blacks walked up and down the street, that was considered a meeting, and Jim Clark would arrest them. They invited Dr. King to come in and speak, and he wanted somebody to go there and mobilize folk to make sure people came out for the rally. So Bevel asked me to get some students and take them to Selma, and I got about eight or 10 students from Montgomery and we went to Selma. We just got out on Main Street and started singing freedom songs downtown on a Saturday, and nobody was arrested. And the SNCC staff was amazed because they said, “We can’t do this, now how can y’all do it?”

This was between New Year’s and Christmas, because on January 1 of ’65, Dr. King came to Selma for his first time, when we had the Emancipation March and the rally. We got this one church on the day of the first and the meeting was supposed to have been at three o’clock, but at nine o’clock that morning, the church was packed and people were all out in the streets, you know, thousands of folks. We had to open all the other churches, cancel services in all the other churches in that area, so that people would have a place to go. That’s how we got the churches open. And that’s what brought the Selma Movement.

The people we hear about is Dr. King, Dr. Abernathy, Andy Young, but they were basically the leaders. The media never talks about the people who got the whippings. I was one of the folk that would go into a town first, and by the time Doctor and them got to town, we done got the whippings. But those kind of folk don’t never get mentioned.

If we get another leader in our lifetime, I don’t foresee it being nothing but a woman. The women’s movement is a movement that’s long overdue. If the story is ever told, women made black folk what they are today. Like, we had Martin Luther King as a leader, but if you check out every march that he participated in or led, every movement that he had, there were women and children, not men. The men stood on the side of the street and watched us get our butts whipped and talked about how bad they was — but they were scared. Wasn’t man enough to say that he was afraid, but that’s what it was, fear. And that was the way we interpreted it to the community and to people around. We got men involved like that. We’ve had movements, man, we told women, don’t even go to bed with him if he won’t stand up for you. In a couple of cities that worked. Men was coming around, saying, “Man, my wife has got me sleeping on the couch, I got to come down here and help.”

This happened down in Selma — not Selma, but this happened in Marion, Alabama, about 20-some miles from Selma. See, we give credit to Selma, but it wasn’t Selma that brought the 1965 Voters’ Rights Act, it was places like Marion, Eutaw, Greensboro. See, we never could motivate people in Selma, Alabama. We motivated young folk, but the adults that participated in the Selma Movement, those adults came from Marion, Greensboro, surrounding areas of Selma because Sheriff Jim Clark wouldn’t let folk register in Selma. We would import people from the rural areas to go to the courthouse to register. But we never could get enough people in Selma involved and so they sent me to Marion, Alabama. That was, I guess, my first time serving as a leader, because when I went to Marion people had to be off the streets at a certain time — Marion, Greensboro, Eutaw, all over those black counties. And we, along with SNCC, went to town and told people, “This is your town, you’re a majority here, and you should have the right.”

We’d been there about two months and the power structure had attempted to arrest me four or five times, but people in the community knew it, especially the women who worked in the houses of white women because they had overheard what was gonna happen if I ever got arrested. So one day they arrested me. They took me to jail and was gonna lynch me and people had come to the jail, saying, “We got him finally.” But it got to Albert Turner, and he mobilized a mass meeting in the church and a march.

When they came out for the march that night, the police just started beating up folk and shooting, and that’s when Jimmy Lee Jackson got shot. His family was known all over that area. That same night, his granddaddy, Brother Kacie, who was about 88, was beat up by the highway patrol. And that went directly over the television because some cameras picked it up, and everybody knew that old man had went and registered to vote. And Jimmy Lee lived from that Thursday he got shot until the next week and he died that following Friday, a week later. We had said we were going to have a motorcade to Montgomery from Selma because of what Jim Clark was doing, but when Jimmy Lee Jackson was shot, Jim Bevel and myself and Mrs. Lucy Foster sorta said, “We don’t need to drive — let’s walk to Montgomery.” That’s where the whole walk-to-Montgomery idea came. Because of Jimmy Lee.

The first day we struck out to walk, marching, we got the dog stuff beat out of us out there on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. We retreated and went back to the church, and that’s when the national call went out. I guess that was my first experience as far as being a leader, because people in Marion, they started calling me Jesus, and when I go there today, man, they still call me Jesus.

Then they wanted somebody to go to Chicago, and Bevel called me and asked me would I come up to Chicago, and the people in Marion didn’t want me to leave. That’s when Dr. King started calling me Shackdaddy. He made a speech, saying that we were shacking with the community, we wasn’t there to live, we weren’t gonna marry the community. Our job was to get stuff started and then move on and get stuff started in other areas. I guess more people know me, man, as Shackdaddy than they do as James Orange.

So I left and went to Chicago in the fall of ’65. We had never seen those type of conditions, and the first tenant council was organized by us in ’65. We had a rent strike and told people don’t pay no more rent to the landlord, pay rent to yourself. We got 10 to 12 thousand dollars taken up in rent. We just took that money, went out and bought some building materials, and put it in each person’s apartment and told them to fix their apartment. And the landlord of that building saw the difference in the attitude of the people who lived there because they was interested in helping their own selves. He gave us that building, gave that building to Dr. King and SCLC.

We went from that part in Chicago to saying, “Okay, we don’t have a right to live in a certain place,” and that’s what brought the marches on open housing.

They said they needed someone to organize the gangs and I went out and started talking with some of the kids and went to the South Side. A couple of kids were fighting and I didn’t know it was a gang fight. I went over there, say, “Hey man, brothers ain’t got no business fighting. Y’all oughta be trying to fight the system and here y’all fighting each other.” And both of em turned on me and I guess what surprised them was I didn’t fight back.

I went to the doctor and just had a busted nose, busted lip. The next morning I went back to the area with Jimmy Collier, who was a guitar player, and a white fellow named Eric Kimburg who was on staff. When I got out of the car, about 25 guys started walking towards Eric. I said, “Hey, hold it, man, now wait a minute. I done took that last whipping y’all gave me last night, but we’re not gonna keep taking whippings. If y’all want to talk about how do you get out of the slum,” I said, “that’s what we here for.” And Jimmy Collier took out his guitar and started singing. The song he sung was “The Ghetto” — we have that on our record, “Jimmy Collier and Friends,” that came out of Chicago.

During the whole Movement, see like, whenever we wanted to get control of people, we started singing freedom songs, that was the best way to get attention and get control. Because whoever was leading that freedom song, at the end of that Birmingham Fire Department uses high-pressure hoses against peaceful demonstrators. freedom song, he had everybody’s attention, and that was the way we kept control of people, even on marches. Like if we saw the police coming, the first song we’d strike out with, “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Us Around” — ain’t gonna let no police officer turn us around, ain’t gonna let no dogs — and that song would go on even if people was being whupped.

So this was the Blackstone Rangers. Then we went over to the Vice Lords, the Roman Saints, the Cobras, and there was a white gang up in Uptown Chicago that Rennie Davis was working with and we got to them, and to the Puerto Rican gangs. We got them together at a gang convention, and Dr. King came to the hotel where we had it. Those guys just sat down and started talking about working together. From that period on, we worked with these guys. We was talking about marching in Gage Park, and I said the best thing to do is get them guys to be marshals. Nobody could see them being nonviolent, but we started having workshops, freedom songs, and taught them the songs that we did in Birmingham. They started out bad, in so many words, but ended up good. And they said, “Okay, we’ll be your marshals.”

The first day we went out there, they had shotguns and everything. So we said, “All right, anybody that’s too afraid to go with no weapons, we don’t want you to go because we don’t want no scared people with us.” That irritated everybody, because we was telling them that they was chicken. We collected their weapons, weapons we didn’t even know they had, four or five boxes full. So all of the Rangers said, “Okay, we’re gonna take care of this side.”

So I said, “The worst thing that can happen is to let the gang kids get together. Why don’t we separate them, put a Ranger, Vice Lord, Roman Saint, Cobra — you know, we just pair them off.” That’s what we did, and they got to know each other. After the first two or three marches, after they saw who the enemy was, we didn’t hear no more on radio or TV about violence with the gangs versus gangs. They tell me that they are just starting back to using that type of violence. Like Chicago was quiet from about ’65 maybe up until about ’73 or ’74, before gangs just really got reorganized, and that was Chicago.

Then Doc asked us to go to Cleveland, so Willie Tabb, A1 Simpson and I went and began working on voter registration and pulling the community together. We had an election and we worked out there with Carl Stokes, and I guess that was the first time I’d ever really gotten mad with a Movement leader. The night the election was over, when Carl Stokes won as mayor, the phone rung in Dr. King’s room. It was Carl Stokes saying he didn’t think Dr. King should come to the victory party because he would polarize the people. And we did all that work, so automatically people just got pissed off with Carl Stokes.

About a week or so later we left and went to Philadelphia, and in Philadelphia we were talking about the Poor People’s Campaign. They had given me the Northeast and told me I had to get people from Boston to Washington, DC, and I didn’t know what to do! I went to Philadelphia at the end of ’67, and I was in Philadelphia up until a week before Dr. King was assassinated.

Doc went to Memphis for a march and they rioted, so that night they called me in Philadelphia and told me to get the first plane smoking from Philadelphia and come back to Atlanta. At the staff meeting in Atlanta, they said they needed somebody to deal with the Invaders, who were one of the rival gangs in Memphis, and talk to people about nonviolence. So I went over to Memphis that Sunday. The following Thursday, Dr. King was shot, and I left, went back to Philadelphia to work on the Poor People’s Campaign.

We had said we were gonna bring one bus from the Northeast to Washington, DC, and by the time we left Boston we had 28 buses. When we left Providence, I think we pulled into New York with 31 buses. We left New York, we had 112 buses and we were supposed to have started with one bus. We marched in Philly with over 50,000 people, just on that day. This is May and June, 1968.

When we got to DC we had too many buses in that Northeast contingent, because the Southern and Midwestern and Western legs had come up, and they halted us in Maryland for about three days. We finally got enough structures completed in Resurrection City that they moved us on in. And when I got off the bus with my folk and was going on back to Philadelphia, that’s when I found out I was the sheriff of Resurrection City. Dr. Abernathy, Bevel and Andy made the decision. They gave me an assignment that I thought I didn’t know nothing about. How do you have a police department without arresting folk and beating people up? That was when I really got off into nonviolence because, at that point, we had everything at Resurrection City that was in Harlem — prostitution, drugs, people hustling this and that, gangs. We was able without violence to break all of that up in about a week or so.

After the Poor People’s Campaign, I went down to Charleston for the hospital workers strike. From Charleston, in 1969, the program that I picked up as my pet program was Operation GAM — Operation Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. That’s what I worked on, I guess from ’69 up until I started working with the labor movement. In Operation GAM, we attempted to get a congressional district in each of those states that was predominantly black and do some voter registration and politicizing.

Now I also worked on the March Against Repression in ’72. We marched from Miami to Tallahassee, Florida; the Democratic National Convention was down in Florida at the time. When we got to Tallahassee with about 10,000 to 15,000 folks, the highway patrol stopped us on the highway and pushed us off the road and said, “We want y’all off the highway, you ain’t gonna walk on the road no more.” I said, “All right, we ain’t gonna do nothing, we’ll just stay here. You go get the governor, and if the governor comes out here and talks to us,” I said, “then we’ll move, we’ll go on further.” About 15 to 20 minutes later, here come a helicopter and the governor landed. Reuben Askew.

The main issue that we was raising was the whole question of commodity foods. They’d give Cubans food stamps and give blacks and poor whites commodities — peanut butter, dried beans, cheese that came in a box. And so we got some of the Chicanos and Cubans in Florida and said what we wanted to do was make sure that if y’all can’t eat commodities why we gotta eat em. That brought back up that whole national program to end the commodity program, and then the food stamps program came into being. We give ourselves, those of us who was participating, some credit for making food stamps a national thing.

Then I worked on the Continental Walk, marching from New Orleans to Washington during the Bicentennial to focus on the connection between the money spent on the Pentagon that doesn’t go to social programs.

After that I got several calls from Andy and Mrs. King and others to work with the J.P. Stevens workers and the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union. I told them I didn’t want to work with labor, because I was with the Civil Rights Movement. But I kept getting the calls for help and so at the beginning of February, 1977, I consented to talk with ACTWU and then I started working with them and that brought me into the labor movement.

It’s a funny thing, man. When I got hooked up with the Civil Rights Movement, me and my daddy didn’t get along, because he didn’t like me being a civil-rights activist. My mother, she was a bootleg beautician — she’d dress hair at home. She had been afraid for what I was doing in the Movement in Birmingham, too. See, my mother’s church was bombed at the time, so I understood why she was scared. But one night I went to a mass meeting, I looked down and saw a lady stand up clapping — and I said, “Damn, don’t that look like my mama.” And I went down, and it was my mama.

Now my daddy, I always thought my daddy was an Uncle Tom, I really did. But when I started working with ACTWU back in ’77, now that’s when my father and I really opened up, because he said, “Okay, you’re doing something that I think you oughta be | doing.” It didn’t dawn on me till maybe six months after I had started working with the union that, hey, my | daddy got fired for organizing a union, trying to get a union in 1957 in | ACIPCO. He had been blacklisted after that.

Every job he’d get, he got terminated from because people found out that he was union. He went to that meeting with a white union man, and back in ’57, you just didn’t sit in no meeting with white folks in Birmingham. Three folk got fired — they told them laid off — a white guy, a white woman and daddy. I guess once I started with the union, that’s when he started respecting my work.

All along, I had been working alongside labor folk. They’re the ones who can make sure a movement has the leaflets, transportation and bond money. People like Ralph Worrell, he’s with District 65, had been trying to get me to be a labor organizer for years, back in the mid-’60s. One thing they showed me was that in the Civil Rights Movement, once we got a community organized, we didn’t have any type of organization, we left a mobilization, but with organized labor you leave an organization that is continuous. In SCLC, we never went and organized no community, we really didn’t. Now we called ourselves organizers, but we really was mobilizers. We could mobilize a community for a shotgun, like for a spur-of-the-moment movement. But now in organized labor your tendency is to set up an organization, and that organization, whether I’m there or not, they know that a certain day each year, they’re gonna have an election. You’ve got a contract to renew, a company to negotiate on an equal footing with, people who you represent day in and day out. In the Civil Rights Movement, we didn’t have that. We got some community organizations that we organized in some communities, but yet still those organizations don’t have the power to go to the power structure and to deal with change.

That was the difference in the Movement. We didn’t develop people and institutions to follow up in communities. Instead what happened was the people who did the most criticizing of the stuff that we were doing was basically the people who ended up getting the benefits. People who were going around saying, “We ain’t got no business going down there registering to vote,” they ended up being elected officials. And they didn’t change things. You got a black power base, you got a white power base, whether you realize it or not. And at some point those two power bases get up and meet, but they don’t ever agree because they ain’t never level. The power structure that is the power structure is always a step above the other guy, because he’s the one making the decisions and coming out with issues. So what they do is give us programs to pacify folks. They co-opt people into federal programs. The federal government has taken a lot of your local leaders and given them federal programs, and when you get money from the federal government it’s hard to fight the government.

And that’s the difference with labor. It focuses on economics and independent security. I’ll give you an example of what I mean. We got a civil-rights bill and a voters’ rights bill in ’64 and ’65. But they don’t guarantee people a decent source of living because they don’t secure an economic base for folks. And that’s where organized labor really could take up where the Civil Rights Movement left off, because we just got the bills but we didn’t get no kind of protection. There is nothing to make sure that if a person had a job he would be guaranteed certain things in his job, guaranteed certain basic rights.

Labor can gain a lot of things from Movement folk, too. Like, if labor would really have gone to the civil-rights organizations when the 1978 Labor Law Reform Bill was up for a vote, they could have really gotten a mass letter campaign going, and they could have even got some demonstrations. Labor is good at pickets, but the Civil Rights Movement is good at demonstrations. The labor movement is good at obedience, but the Civil Rights Movement is good at civil disobedience. They’ve had me working on a couple of marches in the labor movement, and a lot of unions are moving toward those civil-rights ideals.

I still see myself as a mobilizer, but as a mobilizer on a different level. And I’m still called an outside agitator. That was the word the power structure used, and they’re using it now, in organized labor. Some of the same people that I ran up on in the Civil Rights Movement in South Carolina who was fighting the Movement, in Georgia, in Mississippi and Alabama, they’re fighting the labor movement today. Their words, as far as blacks and whites, have changed, but their goals really are still the same. They want to fight change, and that’s all it is.

When I go into the community I’m still looking for people who want change, and if bringing about that change means taking a beating, then that’s what that person would take. Nobody in the Movement wanted to take a beating, but if taking a beating meant giving me the right to sit in whatever restaurant I wanted to sit in, boom, I was there to take that beating. If taking a beating or getting killed meant getting the right to vote, we was there to do that. Same thing as far as open housing, or whatever the issues confronting us were at that time, and still are in organized labor.

I feel very strongly that in a lot of areas labor could really take up in the South where civil rights left off. But it’s gonna have to be some real progressive thinking as far as the whole concept of black versus white, because you got a lot of blacks working in the South, and I think once we could show them, “Hey, that ain’t just a white union, blacks are there too,” then a lot of stuff can happen.

In a lot of areas poor whites are just as bad as blacks as far as the power structure is concerned. They might not do the same things, but they have the same lifestyle. Friday night, Saturday night is when they party, Sunday they go ask for blessings. You gotta teach them how to get blessings all week long. And those blessings go to everybody in the community. You find a worker that’s not organized, it’s a worker that’s always bitching about something, either his home, his church, his school, his job, his surroundings, his community, he’s the worker who’s bitching. But the average worker that’s organized, he’s out doing something in his community. That’s why I see something that could happen with labor, really, with labor and civil rights. On a national level, and in every community.

I guess I go in with an advantage because I know people on all sides, on the labor side, civil-rights side, the church side, economic side, political side. And I can interpret the different sides to one another. But still civil-rights organizations don’t trust labor. And so they gotta start trusting people and work for labor to make sure that neither side makes the bad mistakes they have been making. There have to be coalitions. I could be a labor member and I could be a racist in my heart, but that shouldn’t stop me from working with churches and civil-rights organizations. Why? Because if I come out here and work to help economic development in my community through a grievance procedure or whatever the case may be, that’s not just helping me in my local. That’s helping the community that the brother lives in. And people gotta make that hook-up and that connection.

You could do a lot in a community with a labor union like a civil-rights organization once did, and more. A local could be the political mechanism in that community. The A. Philip Randolph Institute can come in and do voter registration along with the Voter Education Project. A local can conduct a citizenship training program to teach the people how to read and write. Whether we realize it or not, 40 percent of the Southeast is still illiterate — can’t read, can’t write. So organized labor could serve as that mechanism to teach reading and writing programs in and around locals. This isn’t something that you expect to happen overnight, but with the right type of challenge to society, this could happen.

Our union in New York has a druggist program where the person in that area knows if they need some type of medicine, they can get the medicine from our office at a discount rate. But suppose every local was like that? We can run a savings plan, call it credit unions, in Rome, Georgia, where we have a rubber plant unionized, and the members of that local can go and get tires at a discount for their families and friends. There could be a hook-up between the AFL-CIO and any of their affiliated members so they can go up, flash a card, say, “Okay, I need a set of Uniroyals,” and then you could get it at the union rate, you’re a union member. These are the kind of things that could happen with union members that couldn’t necessarily happen because you don’t have the mechanism anywhere else that is as strong and as powerful as organized labor. And these are things people need.

The thing civil-rights organizations, church organizations, labor organizations — all of us — have to do is get involved in the whole concept of organizing. Too often we think our ideas are too big, or if we try something, it might get out of hand. But when we start organizing, we find out that it was us who was too cautious, and the people knew what was on their minds. We don’t have the type of leaders today that we had back in the early ’60s and late ’50s, because if a person pulled you out as a leader that meant that that community and those folk was behind you, and you stayed up with them. In a lot of instances today, the people have gone off and left the leader as far as their mentality and ideas is concerned. Gandhi had it right; he said, “There go my people. I must catch up with them, for I am their leader.”

Tags

James Orange

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.