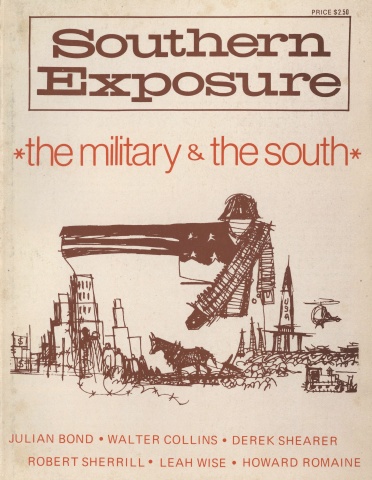

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 1 No. 1, "The Military & the South." Find more from that issue here.

Papers on the War by Daniel Ellsberg, Simon and Schuster, 1972. 309 pages. $2.95.

Militarism, U.S.A. by Colonel James A. Donovan (Ret.), Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1970. 237 pages. $2.95.

Soldier by Anthony B. Herbert, Holt, Rinehard, and Winston, 1973. 456 pages. $10.95.

The High Priests of Waste by A. Ernest Fitzgerald, W.W. Norton Company, 1972. 366 pages. $8.95.

Roots of War by Richard Barnet, Atheneum, 1972. 350 pages. $10.00.

Drop-outs from the defense establishment are becoming more visible these days, speaking out and writing books on militarism in our society. They are like conscientious ghosts roaming the country as living proof of the skeletons in our collective closets. Their words are terse, with a hint of desperation, the tone of someone who has been inside the monster, seen its hydra-headed ugliness and now wants to warn the rest of the nation-before it’s too late.

Daniel Ellsberg is probably the most celebrated delinquent, and his book, Papers on the War, draws heavily on the Pentagon documents he finally managed to leak to the world. His essays, written between 1965 and 1971, recount how American foreign policy makers defined U.S. policy toward Southeast Asia following the 1950 “loss” of China and relentlessly escalated the scale of our intervention in Vietnam out of political expediency.

As a lower ranking policy maker, Ellsberg came to view the war first as a mistake, then as a stalemate, and finally, after breaking through the bureaucratic barrier to apply moral questions to his policy judgments, as a criminal act. Having come to such a conclusion, he became powerless. The very nature of the team partnership between military, government, and business means uncooperative cogs must be routinely pushed out. Henry Durham’s story (elsewhere in this issue) is representative of those who fight boondoggling and mismanagement in their companies only to be expelled like disobedient school children.

Retired military officers are also writing about what it’s like inside the Pentagon. To date the best book in this league is Colonel James Donovan’s Militarism U.S.A. A former president of the Armed Forces Journal, Donovan describes how competition between the branches of the armed services fuels the war machine. Senior officers from each branch demand weapons systems that will get them to the scene of battle first. An invasion of the Dominican Republic or Vietnam become opportunities to test new technologies and mobilization theories plus providing the exploits for further promotions. Private contractors sell the military on flashy new weapons, and the military gets the civilian bureaucrats to let them try the new toys out.

As the books under review here indicate, your analysis of such a circle depends on where you are in it. Like Donovan, his Atlanta neighbor, Lt. Col. Anthony Herbert views the situation from inside the military-but his book Soldier is an autobiographical adventure story of the front-line professional soldier.

Escaping from a west Pennsylvania coal town, Herbert began his military carreer at age 17. He became a man before he had been a boy; he took hold of the rules and regulations of the Army, obeying them to the letter like a newly initiated boy scout who didn’t know everybody else was smoking cigarettes on the sly. Korea became the first testing ground for his almost instinctive appreciation for a good fight—he won loads of medals but elicited the anger of higher-ups. For example,

Once we were being cut up pretty bad by some little bastard who sat tight behind a machine gun and just played hell with us for about five hours, long after the rest of his Chinese friends had bugged out. It cost us a lot of men to get up behind him, and I know he knew exactly what we were doing. ... I had him covered and I shouted at him to surrender when MacCullough, one of the guys in our squad, ran up beside me and poured a full magazine of twenty rounds from his AR into the guy. I rapped Mac in the mouth and the lieutenant chewed my ass out for hitting one of our guys, but Chinese or no Chinese, the dead machine gunner had been one hell of a trooper. He deserved better than he got. If he'd fought like that for us, he would have been a hero.

Herbert came out of the Korean War the most decorated enlisted man on our side and was more dedicated than ever to an Army career. But on the advice of Eleanor Roosevelt, who had joined him on an honor tour of Allied countries, he left the Army long enough to get a college education. More of an intellectual than this book reveals, Herbert kept going back for more schooling until he obtained a masters degree in psychology from the University of Georgia (with a thesis on General Patton's psychology--a man of deep insecurities typical of a professional warrior, he says).

Between Korea and Vietnam, Herbert trained as a member of the elite Rangers and Special Forces, commanded a battalion in the 1965 Dominican Republic invasion, and engaged in all sorts of James Bond escapades. Despite a growing disdain for West Point jelly-fish officers, Herbert continued to believe in the Army, the one on paper with codes and hierarchical rankings necessary for getting the discipline needed to win wars.

But Tony Herbert balked when he found out what the U.S. Army was doing in Vietnam: violating its own rules, torturing peasants, allowing mass murders, supporting high-living senior officers. His superiors tried to convince him their way was the way to win wars--but Herbert knew better. Fifty-eight days after taking command of a battalion in Vietnam, our super soldier was summarily relieved of duty.

When he got back to the states, Herbert launched an attack on the high ranking officers who had covered up the war crimes he reported. Part of the controversy became front page news, but the complete tale recorded in Soldier is even more damning to the military. Cut off at every turn within the Pentagon bureaucracy, Herbert eventually left the Army to push for reforms from the outside. He’s now under contract to write a second book on the alternatives to America’s armed services system.

If wars are necessary (and Vietnam never was, says Herbert), then they should follow the classical pattern of honorable men fighting to the death, fair and square; and Herbert’s book reeks of the supreme self-confidence of a man who knows how to kill you forty different ways. (In person, Tony Herbert’s lack of self doubt about who he is or what he believes allows him to talk with a detached patience and military-style firmness; he’s not intimidated by anyone so he doesn’t have to show off-although some have questioned his credibility).

But those who sluff off Herbert’s charges of corruption and war crime coverups because they can’t stomach his apparent ease in gunning down “the enemy” are clearly missing the point. Those who like to keep the blood and guts of war far in the distance, who favor the Kennedy-McNamara technological warfare where the enemy is never seen, those are the over-civilized sophistocrats who have brought us a new generation of electronic bloodshed where wholesale murder is routine. If wars were more personal to Americans, maybe we’d get involved in far fewer of them. As Herbert reflects on his experience in Vietnam:

When I remember the folly of it oil now, I rationalize a bit and tell myself that there wasn’t time enough to be fully sensitive to the finality of death. . . . When even just one man died or got his fingers blown off . . . it was one hell of a costly battle-especially if you happened to be the guy who got it that day. It’s something generals and presidents can never understand-only mothers, fathers, brothers, sons and daughters and wives. Maybe if I were a general or a president who never went to war with his men and who never risked paying the same price, maybe I’d want to convert the whole damned show into a statistical table to be read solemnly by some broadcaster every Thursday night. . . . If you want to make your war a war of numbers, you have no trouble sleeping. Most generals and presidents sleep well.

But the Pentagon’s numbers don’t even tell the true statistical picture, as Ernest Fitzgerald makes very plain. In 1965, Fitzgerald enthusiastically left his career as a successful cost analyst and efficiency expert to go to work with McNamara’s whiz kids, convinced of their commitment to hold defense expenditures down to the bare bones minimum. What he found was a pack of lies.

He writes his High Priest of Waste with the fervor of the southern Protestant he is, a preacherman bent on rewarding the self-restrained contractors and banishing the self-indulgent, “unprincipled rascals” to eternal hell. He is concerned with malicious waste, not the system of capitalism, with the production of shoddy weapons, not the imperial wars they are used in. Yet he documents the words and deeds of countless government, industry and military personnel to show that waste is not an accident, but the rule.

Unlike Richard Kaufman’s comprehensive The War Profiteers, which meticulously identifies the culprits and the range of federal programs they control, Fitzgerald provides a personal account of how the Pentagon bureaucracy allows giant weapons-makers to bilk the public of billions of dollars. But as with Kaufman’s book (the two men work together on the staff of Proxmire’s Joint Economic Committee), the effect is a clear indictment of corruption and thievery in the military-industrial complex.

“Inefficiency is national policy,” Air Force Major General Zeke Zoeckler told Fitzgerald after he protested the Pentagon’s tolerance for sloppy bookkeeping and massive cost overruns on McNamara’s pet project, the F-lll. With one weapons system after another, Fitzgerald describes his attempts to halt waste only to be rebuffed by a higher layer of the bureaucracy. Time and again, he gathered information from his “secret sympathizers” inside a contractor, held “revival meetings” for top brass to reinforce the litany of cost saving, and challenged the “Ape Theory of Management” which said if you hire enough people and spend enough money, something worthwhile will surely result.

In the end, Fitzgerald was called before Senator Proxmire’s Joint Economic Committee to talk about weapons contracting. To the disgust of his superiors, he wouldn’t lie. He confirmed Proxmire’s suspicion that the Air Force’s “pet dinosaur,” Lockheed Aircraft, was running $2,000,000,000 over its original C-5A contract of $3.7 billion. With that admission, all hell broke loose. Georgia’s Senator Richard Russell, chairman of the Appropriations Committee, was furious: the C-5A was being made in Marietta, Georgia! The Secretary of Defense’s office scurried around trying to find some evidence that would discredit Fitzgerald or his testimony. A rematch was scheduled and the Pentagon in the person of Assistant Secretary Bob Charles planned to present Proxmire’s committee with manipulated figures that would contradict those Fitzgerald would offer. The day of the face-to-face contest came, and Fitzgerald, with a characteristic personal touch and sense for comic relief describes it:

As I walked out the [Pentagon’s] River Entrance I saw below me on the sidewalk a sizeable knot of Bob Charles’ principal associates—perhaps a dozen people—gathered around the small cavalcade of cars waiting to take them and the Assistant Secretary to Senator Proxmire’s hearing. Secretary Charles’ car, complete with permanently assigned uniformed chauffeur, telephone, and rear seat reading lamp, was first in line, followed by a couple of G.I. staff cars to haul the lesser weenies. I was riding the bus.

The bus ride from the Pentagon to the new Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill was probably the low point of my adventures in the military spending complex. I was strangely and uncharacteristically depressed by the array of power against me. I had to remind myself that ... I had the rascals outgunned. I was right, and I had all the facts I needed in my head. . . . Bob Charles had the unenviable task of defending a lie. . .

As I got off the bus, my recovery was complete. There just across the street at the back of the new Senate Office Building was Bob Charles’ cavalcade of official vehicles discharging their loads of Assistant Secretary and weenies. For some reason, the fact that I had traveled to our mutual destination just as fast and far more economically completely restored my competitive spirit.

The Pentagon lost that round of Senate hearings. But they still had the upper hand; one by one Fitzgerald’s job responsibilities were narrowed until his position, with the approval of President Nixon unless he “mis-spoke” (whatever that is!),* was unceremonially liquidated. Ernest Fitzgerald became persona non grata.

By my stubborn adherence to facts ... I had placed myself in opposition to the Air Force “position” that all was well with the big plane. ... It was an article of faith. Those who denied it were heretics and blasphemers. I had denied the true faith and consequently was an outcast..

Throughout his detailed account of fighting over this or that rip-off, it is this sense of moral battle that keeps Fitzgerald’s book lively and highly readable; the struggle against complicated Pentagon contracts and bureaucratic red tape became a personal crusade against the “rascals,” “thieves,” “weenies,” “bean-counters,” “cost-estimating Calvinists,” “conscientious objectors to active warfare on high costs,” and “lollygaggle of contractors and military men.” Fitzgerald was “a one man band playing the cost-reduction tune” in the face of an impressive array of witch doctor-like Pentagon economists who “neither questioned nor thought much about fundamental causes and effects”; they just waved their slide rules and embraced waste as necessary for high employment and growth in demand.

In his final chapter, Fitzgerald offers a prescription for combating these technocrats and their superiors. First you must recognize the bad effects of a defense establishment that lies, cheats and steals: (1) shoddy weapons production has jeopardized our actual military preparedness; (2) a fat defense budget that stimulates inflation and retard competitive enterprise has helped weaken the fiscal health of the U.S.; (3) widespread thievery by the military spending coalition is eroding our nation’s morality and respect for law and authority.

Realizing these things, Americans must unite to cut the Pentagon’s life line-its money supply. They will have to resist the big spenders’ appeal to fear (the communists will overtake us) and greed (we make jobs). The “permanent cure” requires changes in the nation’s political economy, Fitzgerald admits, but in the meanwhile, citizens should mobilize themselves and others as a voter and taxpayer lobby, carefully educating themselves, then selecting this or that defense contract or boondoggling congressman, and leveling all guns on the target. “When sufficient numbers of taxpayers are so aroused, they will simply outvote the beneficiaries of the boondoggles.” Now all we need is the numbers. . . .

For an analysis of this warrior nation’s political economy that could serve as the backbone of a strategy for the “permanent cure,” turn to Richard Barnet’s Roots of War. It’s not a personal account, and it won’t sell as well as Herbert’s book or read as cleverly as Fitzgerald’s. But it is without doubt the most lucid, penetrating account available of the factors propelling the U.S. from one war to the next. It is so full of provocative thoughts and sub-themes, it could be easily expanded into several volumes.

From his vantage point in John Kennedy’s State Department and later the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, the Harvard educated Barnet observed the “national security managers” discuss, plan, and implement foreign policy for America. The early sixties was a time of rearmament for the U.S. under the leadership of a darling liberal and a host of Keynesian advisors. When the point got through to Barnet that things were getting worse instead of better under the speed-reading technocratic managers brought in by Kennedy, he left the government and helped start (with other young turk government drop-outs) the now famous Institute for Policy Studies, a Washington, D.C. based clique of intellectuals that has had a hand in shaping left-liberal thought for a decade.

Roots of War is Barnet’s sixth book, the fifth since he organized I.P.S. It is less documented than his excellent reference work on U.S. meddling in other countries (Intervention and Revolution) but more analytical than the essays comprising The Economy of Death. In a sense, it is the summation of the analysis of American foreign policy and the “national security state” developed over the last several years by I.P.S.ers Marc Raskin, Ralph Stavins, Art Waskow, Leonard Rodberg and Barnet.

Barnet does not attempt to explain how this or that war started, but rather to give a systemic answer to the question “why those who have been in charge of defining and meeting the threats facing the United States have determined that the national interest must be pursued by war and preparation of war.” Combining cultural, historical, and political approaches, Barnet divides his analysis of the “national security managers” into three general sections: the bureaucracy’s internal dynamics, its relationship to the business elite, and its manipulation of the public.

Barnet is clearly at home in the first section in describing the inner workings and rise to power of America’s foreign policy bureaucracy. Reinforcing Herbert’s point about depersonalized warfare, Barnet shows how the federal bureaucracy is divided so that some plan the war, some give the orders, and others do the killing. Under this system war crimes become the responsibility of no one, but simply the automatic result of policy. Violence is the natural product of a bureaucracy which is fascinated by new techniques of power and which pushes technology to its limits to achieve “national goals.” “Having made the bomb,” Truman explained in 1945, “we used it.”

But Barnet does not analyze the degree to which technology has determined policy (as does Donovan’s Militarism U.S.A. and Michael Klare’s War Without End); rather he sees a war-prone foreign policy arising from the security managers’ conception of the interests and goals of the U.S. The goal, of course, has been expansion; indeed, since its beginning, American leaders have sought to control greater and greater portions of the globe. We are in Southeast Asia because we are in Texas and California and Hawaii. The techniques of expanding control are sanctified by “a powerful imperial creed” which has shifted from the Manifest Destiny doctrine to the post-World War II ideology of “world responsibility.” With numerous well chosen quotes from the bureaucrats’ private and public statements, Barnet shows how this ideology has become a compulsive duty, an ethic, a battle cry for a whole generation of national security managers who entered government after 1940-men like Dean Acheson, Dean Rusk, Robert Lovett, Clark Clifford, John Foster Dulles, John McCloy, James Forrestal, Averill Harriman, McGeorge Bundy, and Walt Rostow.

World War II is the watershed in Barnet’s analysis of the national security managers. Others, notably Columbia University’s Seymour Melman, argue that the major turning point in the creation of the defense establishment and centralized state capitalism came with the rationalization of the Pentagon bureaucracy under McNamara. But Barnet’s concern with the origins of the national security bureaucracy, its Cold War ideology and quest for a permanent war economy, correctly pushes him back to the great war.

For after World War II, the national security agencies had grown in civilian employment to 3,000,000 people from the 1939 level of 80,000. The defense budget leaped from 1.4% of the GNP before the war to a remobilized level after 1948 of roughly 8%. Agencies experienced in foreign and military affairs literally took command of the government. Dilettante ambassadors and crony advisors were replaced with lawyers and bankers trained in managing warfare, men who responded to the challenge of America’s opportunity for world control. The business elite, discredited by the Depression and at first reluctant to mobilize under F.D.R., came out of the war as servants of the nation, and they pushed to maintain a partnership in which they could reap profits, expand their markets, and come off as the good guys. Conversely, Congress lost most of its clout in molding foreign policy:

In the 1930’s Congress exercised a powerful veto on military spending, refusing to fortify Guam and, only a few months before Pearl Harbor, passing the Selective Service Act by a single vote. In 1938 President Roosevelt had to summon all his political powers to block the Ludlow Resolution for a constitutional amendment forbidding the President to send troops overseas without a national referendum. Less than ten years after its narrow defeat, his successor secured broad Congressional support for the President’s right [the Truman Doctrine] to use American military power at his discretion to put down revolutionary movements abroad.

The new managers from corporate law firms and high finance knew how to manipulate language, stretch the law, and calculate risks in order to serve their new “client.” While respecting loyalty and duty (what Barnet calls “the supreme bureaucratic virtues”), they were not what some have described as mindless technocrats who merely fulfill their designated role in the larger machine. Rather, these men felt themselves among the elect by virtue of their worldly success; their Calvinist upbringing—invariably the case, Barnet points out—led them to value expediency above all else in achieving their lofty goal; and the widely accepted Niebuhrian neo-orthodox rationale which made a nation seeking its intelligent self-interest immune from moral questioning gave them the self-vindicating authority to fashion a U.S. policy of world control.

In this context, the national security managers began to work forcefully as a team. With the death of F.D.R., they formulated “the collective picture of the world adopted by the uninformed and ill-prepared Harry Truman,” and they continue to “structure” presidential choices to this day. Nixon’s decision to invade Cambodia was only possible because bureaucrats supplied him with success—predicting scenarios (which, incidentally, were originally developed by the J.F.K. bureaucrats).

In this game of power, Barnet identifies two rules: (1) don’t let your rivals “become powerful enough” to threaten your ability to define a situation, and (2) every nation is a potential contestant in the global game. The American public is more or less a pawn in this contest, consciously manipulated to turn what Barnet identifies as their natural isolationist tendencies (i.e., chauvinistic self-indulgence) into a rationale for continuing world domination.

Following Dean Acheson’s policy of gaining popular support by making things “clearer than truth,” the bureaucratic managers, in Barnet’s words, “alternatively frighten, flatter, excite, or calm the American people. They have developed the theater of crisis into a high art.”

Political considerations come into play insofar as the other party may label your proposals a “white flag” policy, much as Laird did to McGovern. Thus Kennedy was persuaded to okay the Cuban intervention rather than face the consequences of being the President that let Russia put missiles only ninety miles from our shores. And a war weary Dwight Eisenhower, afraid of being labeled soft, let a minister’s son, John Foster Dulles, install a foreign policy of winning converts to Americanism through the threat of nuclear hellfire.

Small wonder, then, that the excitement of crisis management and the machismo ethic of handling violence with distant comfort made this generation of national security bureaucrats a team of highly aggressive, disciplined wielders of power—not unlike Herbert’s professional killers. But how do these men make decisions, choose priorities, weigh options; how do they decide to intervene here or there, to support this or that government?

In the second part of his book, Barnet examines this question in light of whether these policy bureaucrats actually exercise power themselves or whether their decisions are determined by the interests of a business elite. In developing a historically valid theory of managerial power, this is a critical question.

On the one hand nothing in their class background or education would suggest a division of interest between the bureaucrats and the capitalists. In fact, the matrix of values out of which the national security managers define foreign policy “coincides” wonderfully with the business creed of expanding capital. Members of the two groups shuttle back and forth so often that the post-war policy of political and economic expansionism has achieved an unquestioned legitimacy. A foreign policy which promotes development of other countries along lines favorable to U.S. business is as “natural” as believing in progress: both the policy and the faith rest on the racist assumption that furthering the systems of private capital and stable government is as good for them as it is for us.

But even though 60 to 86% of the national security managers come from big business, the two groups don’t always see eye to eye, says Barnet. And here’s where the sticky part comes. The short range, tangible goals of corporate executives are occasionally in opposition to the long range, intangible goals of the bureaucrats. The conflict may give rise to the State Department stopping Ford from selling armored trucks to South Africa or a Senior Advisory Group of businessmen telling President Johnson to cut down or cut out the Vietnam War.

Since the mid-sixties, examples of such rifts have qualitatively changed. The repercussions of a belligerent foreign policy in Vietnam have now shattered the monetary and trade systems which gave U.S. business its global superiority after WWII--and the multinational corporations are raving mad. “Ironically, the quest for an empire which was supposed to expand American influence has left the American economy more and more vulnerable to the decisions of foreigners.”

To Barnet the very fact that the Vietnam intervention could take place and continue so long indicates foreign policy power is held by the national security managers. Business knew better, but their “influence” was not the same as the “power” of the bureaucrats to start and stop wars. In a situation of heightening tension, Barnet asks whether new business forces could overcome the political bureaucrats and inaugurate a new era of global peace? Or are imperial wars inevitable results of capitalism itself?

Contrary to Marxist-Leninist theory, Barnet argues that war is not a logical outgrowth of corporate capitalism: it involves a political rather than an economic choice. It is now theoretically possible for multinational corporations to prosper better through trade with leftist governments rather than launch wars to overturn them. And if big business doesn’t realize this (some already do), then the “reason will not be the iron laws of economics but political inflexibility.”

Even under such enlightened capitalism, Barnet foresees no end of the domination of the weak by the strong and the insatiable appetite for growth. But these are viewed as “an inevitable part of human nature,” rather than intrinsic to the capitalistic political economy. We can at least get rid of the imperial wars, Barnet suggests, by (1) shrinking the national security bureaucracies and reasserting popular control of them, (2) shifting government funding to involve private industry in solving social problems rather than producing weapons, (3) encouraging business to assist technological and economic development under arrangements equitable to the host country, and (4) politicizing foreign policy issues to increase a “new internationalism” consciousness which recognizes our survival in global terms.

Unfortunately, I think Barnet’s own evidence disproves his assessment of the relation of bureaucratic and business power in our society: he mistakenly shifts from identifying who can start wars to who defines foreign policy powers. Historically, the national security managers have implemented long range policies which would benefit the American economy. Their decisions have been structured by the interests of U.S. corporations rather than the reverse.

In some cases, short range business interests have clashed with the long term goal of increasing the sphere of U.S. control; and there are certainly lively debates within and between each group over what decision should be made. But in areas where business has established a firm pattern of operation, such as Latin America, foreign policy choices follow this lead. In the Middle East, where oil and Jewish interests conflict, the bureaucrats must pursue a middle course. The fact that the bureaucrats could get America involved in Vietnam is less an example of their power over business than a reflection of the degree of their power in areas where business is only casually interested. With the rise of the multinational, increasingly expansionist corporation, the areas where security managers can set policy along Cold War lines are vastly diminished. These firms are now demanding long range planning by new bureaucrats who recognize the need for global trade relations. The clash, therefore, is not between business and politics, but between an old school and a new, each with economic and political components.

Finally, it seems that Barnet’s treatment of exploitation of the weak by the strong as human nature is no more rational than the Marxist notion that it will continue as long as human behavior is structured by competitive, expansionist capitalism. And I think it doubtful that the demand for equity by the poor can be ameliorated with capitalistic trade rather than lead to more war. This is not to say that war will end with socialist regimes, as the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia illustrates. It seems clear that as long as competitive, expansionist institutions define human behavior—whether their goals are greater wealth, greater territory, or greater political control—the result will be fighting. To change these war-breeding institutions, one may as logically choose the Marxist understanding of exploitation in terms of class behavior, and thereby work toward a classless society, as choose Barnet’s hope that the multinational capitalists can be forced out of enlightened self-interest to moderate their plundering tendencies and their pre-occupation with endless growth.

Whichever course you wish to take (and the one may be a step toward the other), Barnet’s Roots of War is an immensely informative analysis of U.S. political power from the Cold War to Vietnam. Unfortunately, it is too Washington oriented to give a sense of how foreign policy is made; there is too often a feeling that the security managers are not connected to other forces here and abroad. What we now need are analytical works describing the interrelations of regional power structures with the bureaucratic and corporate elite, so we can identify the targets we need to attack on a local and regional level.

*The day after President Nixon boasted of personally firing Fitzgerald, his press secretary rescinded the comments suggesting the President had “mis-spoke,” apparently confusing Fitzgerald with another victim.

Tags

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.