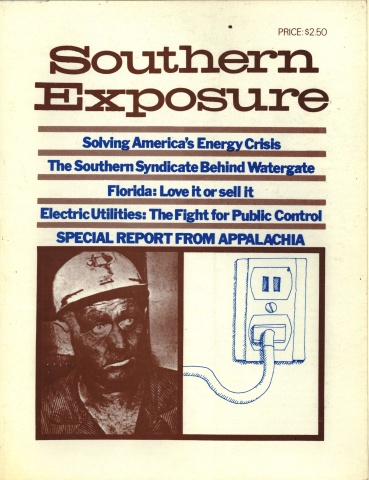

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 1 No. 2, "Special Report from Appalachia." Find more from that issue here.

And Daddy won’t you take me back

to Muhlenberg County

Down by the Green River where Paradise lay?

Well, I’m sorry my son,

but you’re too late in asking.

Mr. Peabody’s coal train has hauled it away.

Then the coal company came

with the world’s largest shovel,

And they tortured the timber

and stripped all the land.

Well, they dug for their coal

’til the land was forsaken,

Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man.

“Paradise," by John Prine. ©1971 by Walden Music, Inc., and Sour Grapes Music.

John Prine is not joking when he says that Muhlenberg County has been hauled away by the Peabody Coal Company. For all practical purposes—like farming—the country might as well be the moon; its craters are deeper, its land more barren, its productive capacity more distant. And to top off some awkward technological symbolism, Peabody and the Tennessee Valley Authority stripped the entire town of Paradise, birthplace of Prine’s father, and built the world’s largest coal-burning steam plant on the town’s remains and named it the “Paradise Steam Plant.” All the townspeople were expelled. The only thing left of the town is the Smith Family Cemetery. The dead remain to look out over the landscape at monstrous shovels, smoke palls from the steam plant, the dust storms stirred up by 100-ton trucks, altogether, the “progress of man.” But at least they left the dead in their graves.

Muhlenberg is in the flatlands of western Kentucky where strip mining is supposedly “better,” at least the dirt and acid cannot spill down mountainsides to destroy someone below. In eastern Kentucky, the people are not so lucky. Both the stripping techniques and the attitude of the industry differ. In a word, in eastern Kentucky not even the dead are protected from the strip miner’s bulldozers. Just ask Eva Ritchie.

Well, in the year ’60, the early part of ’60, they was stripping’ —the Knott Coal Company—back in there. We owned this property at the time, and I had a baby buried back in there, and my husband’s sister had a baby buried back there. Well, my old man’s got miner’s asthma, and all the time he was smotherin’ so bad he couldn’t get up there, and I was in bed with the flu. And I said, “Well, I’ll try to get up there,” but by the time I started up to where the graves was, why, my father said to me, “You needn’t go up there. You’re too late. They’ve pushed the graves out.”

Well, Ansel Combs was on the bulldozer at the time, and he stopped. He said, “If it takes my job to push these babies graves out, I hain’t going to do it.” And Cush Adkins climbed up on the bulldozer and he cursed. I belong to the Regular Baptist Church. I don’t like to use the words that he used, but I will. He said, "Damn,” he said, "Damn it, you get off there, I’ll push them out.” So Cush climbed up on the bulldozer, and he pushed the graves out. Now it’s what they said, one that stood by and saw this. And they come up with the babies’ caskets. They throwed ’em over the hill.

As the scale of destruction grows in the mountains, so does the fear that a whole generation of the living may be either drowned by a giant strip mine-induced flood or more slowly expelled by a whole region gone dead and turned into a kind of eerie energy reservation where no laws apply and no man lives. Such energy parks were suggested in early June by the Nixon administration. If such a policy of writing off certain areas for necessary destruction to meet the energy crisis is officially adopted, the coalfields of Appalachia will probably be the first area to be so designated. No other area of the nation has been so desecrated or has such a vast supply of coal, gas, and water yet untapped. Fear is rising, legitimately, that it’s “goodbye Appalachia.”

What is Strip Mining?

Strip mining as a process is frightening in itself. After prospecting has determined that a minable coal seam lies among the other rock strata of a hill or mountain, the strip miners cut a road through the timber so they can haul to the site their heavy equipment—bulldozers, earth movers, power shovels and front-end loaders. The trees, plants, earth, and rock covering the seam are called “overburden.” This intricate web of life and life-support is blasted loose and pushed by bulldozers down the hillside, becoming as the seam is exposed, a massive, unstable apron at the base of the hill that has been named, appropriately, “spoil bank.” The spoil bank never stops where it lands but slowly, by inches, or in the leaps and bounds of a landslide, obeys the law of gravity. Sometimes it merely uproots trees in its path and blocks streams and roads. But sometimes these masses of rock and earth avalanche into homes or farms.

After the overburden has been removed, the result is a flat bench, resembling a roadbed, along the side of a mountain. Towering vertically over the bench is a man-made cliff, or high-wall, sometimes 100 feet high. The high-wall and the bench form a ring around a hill, or a ridge line, with islands of vegetation remaining precariously on the top of the hill. To expose the coal the strippers have created a gash in the hillside. They have removed the earth from the coal.

Recently it has become more and more common for strip miners to decapitate an entire hill to expose the layers of coal. The hilltop, scraped and blasted away in layers, is shoved over the hillside. As the techniques of strip mining are improved, the ribbon scars on the hillsides today may seem more and more like innocent wounds compared to the possibilities technology has in store. Present techniques allow strippers to dig only about 185 feet beneath the surface, but someday it may be possible for them to dig as deep as 2,000 feet.

When the coal seam is exposed, it too is loosened with explosives. Then power shovels and front-end loaders scoop it up and load it into 30-ton trucks, which, carrying their heavy burden, warp, crack and pulverize roads and highways, seldom with any reprimand from public officials.

If the operator is in a hurry, he may not even expose the coal seam from the top. Instead, his bulldozers cut a narrow bench until the edge, or outcrop, of the seam is exposed. Then giant augers, sometimes seven feet in diameter, move into the seam as far as 200 feet into the side of the mountain and spiral out the coal. Auger mining is also done in conjunction with strip mining if the operator wants to retrieve the coal that remains in the high-wall. Augering is practiced after stripping because sometimes a seam lies too far down the side of a mountain for the operator to remove, economically and speedily, all the millions of tons of overlying mountain.

Power shovels and draglines have long been used in building and road construction, but the country’s demand for coal has bred a strain of giantism into earthmoving machines. A generation ago, these earth movers took about 40 cubic yards to a bite, but now they can scoop up as much as five and a half times that. “Big Muskie,” wide as an eight-lane highway and standing 10 stories high, is the largest earth mover in existence. Such a machine is now stripping away in southeastern Ohio at the rate of 220 cubic yards a scoop.

The eastern Kentucky coalfields have gone through periodic boom-bust cycles for decades, the most spectacular being the peak year of 1947-48 and the complete collapse which followed for 10 years. Automation and declining coal markets cost thousands of miners their jobs. Mountain families headed for the northern cities, much as black people were forced to do by the collapse of cotton tenancy in the South.

Energy markets changed fast during the 1950s: railroads switched to diesel oil; homes began using gas, oil and electricity for heating and cooking. The only stable market was coking coal for steel plants, and this type of coal was usually mined in “captive” mines owned and operated by the steel companies themselves. For the smaller independent mines where most miners worked, there were few markets available. The major exception, and one which was to have major impact on the area, was the rapidly mushrooming national demand for cheap electric power supplied by coal-fired plants.

During all this time the primary method of mining coal was deep mining, through the use of drift mines which followed the horizontal seams of coal underlying the steep terrain of central Appalachia. Two major technological advances during the 1950s played a tremendous role in the present situation. The first was the development of the “cyclone” furnace, an inverted cone 200 feet high which feeds coal under pressure into a furnace producing extra-high temperatures. The heat is converted into steam and used to produce electric power. The second advance was the development of huge mobile earth-movers—shovels, draglines, highlifts, giant bulldozers—capable of literally moving mountains in very short periods of time. These two advances brought about the development of strip mining as we know it today. Strip mining for coal began on a large scale in Appalachia in the early 1960s, although it had been used sporadically since World War II. Because the cyclone furnace produces such high temperatures, it can use coal containing impurities that would previously have been unacceptable on the market. In deep mining, coal lying near the surface near the point where it “crops” out on a mountainside—is left behind, generally because it is mixed with dirt and slate and also because the “outcrop” area is unstable geologically and presents a threat to miners working underground. The strippers, able to sell the relatively low quality coal in an expanding market, concentrate on the “outcrop” areas.

Until about 1960, strip mining was primarily a way in which small-time operators could pick up

emergency short-term contracts from the utilities or steel companies whenever a larger company couldn’t meet demands for coal. It was an unstable, high-risk, low-profit business. Three factors kept it going: first, the ease with which a company could obtain equipment on credit, lease some land, and be in business almost overnight; second, the speed with which coal could be produced; and third, the high productivity compared to the slower, more expensive methods of deep mining.

Mr. Peabody’s Coal Company

“Power for Progress”—meaning electric power— is Peabody Coal’s motto. An investigation of this company’s operating record in the coalfields of western Kentucky reveals, however, that the kind of power it wields best is that which extraordinary profits and bigness have always conferred upon those crass enough to use it—raw political power that stymies every effort of local and state government to regulate the company. A review of Peabody’s climb to the position of number one coal producer in Kentucky shows that every device for manipulating small landowners, politicians, state reclamation inspectors, and the legal profession has been used by the company. Where enormous economic power has not given enough leverage, the company has found outright violation of the state’s strip mining regulations to be acceptable. Peabody is owned by the Kennecott Copper Corporation of New York City. And it would be only a slight exaggeration to say that Peabody “owns” TVA.

The infamous political and economic power of the coal corporations of Appalachia cannot rival the magnitude and frequency with which Peabody has exercised the most base of manipulative instruments available to coal companies to further its advancement. Trampled under the feet of Peabody’s rise are the vestiges of hope that the government’s capacity to regulate coal company powers could outrace the giants. The losers in the battle are Kentucky’s “little people” who have been driven from their homes, had dynamite blasts rock their homes, and who have watched in amazement as the unbridled giant destroyed their own and their neighbors’ way of life without the slightest reprimand from public officials. (Incidentally, it might be added that Peabody last year had the highest number of fatal accidents in its mines of any company in America.) Examples of this company’s abuses of people and land abound.

□ In researching the company’s record in the Division of Reclamation in Frankfort, the office that enforces Kentucky’s strip mining laws, we found that Peabody has succeeded in removing all the residents from the entire community of Morehead in Muhlenberg County. Since Kentucky law prohibits strip mining within 100 feet of a public road, coal companies must persuade the County Judge to declare the roads of no use to the county and send a copy of this declaration to the Division of Reclamation. (The roads of Morehead were thus condemned in the

letter reproduced in the box.)

We asked a Division of Reclamation official about Peabody’s success in the Morehead venture:

Q. How many people live there?

A. Not more than 500, I don’t think.

Q. Did they all sell to Peabody?

A. They had no choice. Everybody knows that they had no choice about selling. If they decide they want what you have, they’ll blast you out. Sure, they force people out.

Q. Does Peabody do this kind of thing often?

A. Peabody is the worst in this. They close roads every day. All they need is to get the Judge to write a letter and we have to let them strip. They’re forcing old people out of their homes all over the place. They just buy everyone around a person and then start pressuring him to sell. They always sell.

Q. Do the County Judges ever object to giving public roads to Peabody?

A. No, they have the Judge in their pockets. Several magistrates in Muhlenberg County work for Peabody. When they decide they want to strip a road, they’ll hire a magistrate who doesn’t work for them if it takes that to get the court’s permission.

Q. Does Peabody pay the county for the roads?

A. No, it looks like, at least, that the coal that is under a public road should belong to the public, but that isn’t the way it is.

□ Peabody Coal has also been assisted enormously by TVA’s development of the long-term contract for supplying strip coal. In the words of an industry magazine:

The long-term contract, committing Peabody reserves to the growing complex of power plants in the U.S., has been for a long time the backbone of the company’s business and a basic factor in its success. That is not about to change. The marketing philosophy of the company recognizes that long-term contracts are good for the coal producer and good for the power industry. (Coal Age, October, 1971)

As mentioned earlier, one of the most glaring announcements of this pair’s cooperation came in June of 1965. TVA announced in Washington, D.C. that it was expanding its Paradise Steam Plant in Muhlenberg County to build the world’s largest generating unit -- costing $130,000,000 and producing 1,130,000 kilowatts of power. TVA said proudly that the new unit would consume 10,500 tons of coal a day. The supplier under a long-term contract, they said, would be Peabody Coal.

Ironically, on the same day that the new TVA unit was announced in Washington, the Attorney General of Kentucky announced in Frankfort that the state was suing Peabody Coal for violating the state’s strip mine control law. Not only was Peabody not obeying state regulations, they were operating without a strip mine permit, without filing a reclamation plan for the land prior to stripping it, and without posting bond or paying acreage or permit fees as required by state law.

□ In 1971, TVA used its power of eminent domain as a federal agency to force 12 landowners in Union County to allow it to build a 12 ½ mile overland conveyor belt -- the world’s largest - to connect Peabody’s Camp No. I and Camp No. II coal mines to a river outlet. The two mines are actually owned by TVA but operated by Peabody. Twelve landowners went to court to prevent the monstrous conveyor belt and its concrete supports from being placed on their property. Twelve landowners lost; Peabody and TVA are now joyously watching the conveyor run 30,000 tons of coal a day.

□Peabody Coal last year produced 17.5 million tons of strip mined coal in western Kentucky. That was 26% of all coal strip mined in Kentucky, the nation’s largest producer of stripped coal. The company employs 2,300 people in Kentucky and has an annual payroll of $26 million. Peabody owns a total of 202,705 acres of Kentucky land. The political power that this wealth and productive capacity gave the company has gained it many friends in public office, and apparently allowed the company to maintain one of the worst records of any strip miner in Kentucky without challenge from the state.

On October 4, 1969, Peabody’s River Queen Mine’s application for a permit to strip mine appeared to be in jeopardy. This permit – necessary to start a new 125 cubic yard shovel, the biggest in the state at that time - was particularly important. However, Peabody was behind in its grading and backfilling, an important ingredient in the prescribed reclamation process. (Before acquiring a permit, the state law requires an operator to submit a reclamation plan or a “time schedule” by which he promises to grade and plant the stripped land. The law says that if this schedule is not followed, a notice of non-compliance shall be issued and the permit is to be suspended. If the operator doesn’t comply, the state can then revoke his permit and not issue another one until all requirements have been met under the old permit.)

The River Queen had been cited eight times on inspection reports since April for not keeping grading current and had already been given two 45 day extensions since then to catch up on its schedule. The situation looked serious; at least, serious enough for President Edwin Phelps from Peabody’s St. Louis office to go to Frankfort to plead the case before the State Reclamation Commission.

On October 7, Peabody requested another 45 day extension and received it. They also were issued the new permit. This action prompted the western Kentucky reclamation supervisor Fahy McDonald, who was subsequently replaced by C.C. McCall, to remark: “We’re just at the point in western Kentucky where we wonder who we’re working for – Peabody or the state.’’

Ironically, Peabody Coal claims to be a leader in stripped land restoration, one of the key elements in the controversy over whether strip mining should be permitted or abolished. Coal Age summed up Peabody’s reclamation claims as follows in an October 1971 gush about the company: “Meeting all legal standards on land relcamation and environmental quality is the immediate goal, but exceeding the standards is the ultimate aim.’’

□ In interviews with us, the officials of the Division of Reclamation denied that Peabody could in any way claim to be an exemplary reclaimer of land and provided insight into how Peabody exercises power over the Division. “Because of their size they were able to get away with some things they probably shouldn’t have. Our biggest problem with them in fact was doing things and then coming to us and asking permission later. They haven’t gone out of their way to cooperate. We have to keep after them, like we do all operators,” said Buddy Beach, Acting Director of the Division.

C.C. McCall, the Division’s Supervisor in Madisonville confirmed Beach’s problems with Peabody. To regulate all western Kentucky strip mining - about 34 million tons, 17.5 tons produced by Peabody alone -- the state Division of Reclamation in Madisonville has according to McCall, “seven people - one secretary, myself, and five inspectors.” The vigor with which these five inspectors examine Peabody came up continually during our investigation.

We asked Beach if it were true that Peabody had duck hunts, beer busts, and parties to which it invited the state inspectors. “There haven’t been any lately that I know of,” he replied. McCall said that he could not recall any lately either. Neither denied that this was a common practice in the past, but said it was not happening now under their direction of the Division.

When we asked McCall about any favors the St. Louis officials of Peabody do for the Division, he replied, “I’ve been out to dinner with them and they paid. They’ll buy your lunch if you’re around. If they can’t take you out, they feel snubbed.”

We asked Buddy Beach if he knew that Peabody bought lunch and dinner for his employees. His reply: “They’ve bought my lunch at times. I don’t think it’s out of line. In some respects it could improve our enforcement relationship.”

Another employee of the Division told us that Peabody gives a country ham to each inspector at Christmas. In a reluctant interview the same person said, “. . .They pretty well give something to everyone. The beer busts have slackened up a little.”

A starting inspector with the Division draws a total monthly check of $482, before taxes and benefits. “All my boys are new,” McCall told us. All employees interviewed denied receiving or knowing of anyone who received extra cash from Peabody. It would appear from the coziness of corporation and regulator that extra cash would be unnecessary to gain favors from the inspectors and the Division. We asked Beach about his confidence in the inspectors. “We have some who ought to be moved, but I can’t do it unless they are a complete deadweight.”

The Division of Reclamation announced in April, 1972, that it had secured a grant totaling $460,000 from the Environmental Protection Agency to conduct a demonstration on treating acid water before it goes into streams near strip mine sites. The demonstration will be carried out on Peabody Coal Company’s Vogue Mine in Muhlenberg County. We asked Beach how expenditure of taxpayers’ money could be justified to a company that had so consistently demonstrated it had no respect for the public’s regulations. “Well, you have a point,” he said, “but the money was available.” Peabody put up a matching grant of $20,000 to secure the funds. Beach said there were “plenty” of places where the demonstration could have taken place, but the Vogue mine seemed “ideal.” In the meantime, if past experience holds, Peabody will get considerable public relations mileage out of the grant and continue to violate regulations and to make fantastic profits.

□ With the words, “I just wanted everyone else to know that everybody here is not an ecologist,” Representative Omar Parish, Jr., created the first major flap of the 1972 Kentucky General Assembly. Parish had placed water glasses bearing the slogan “We Dig Coal” - the insignia of the Kentucky Coal Association - on the desk of each of the House’s 100 members. The controversy developed because the glasses did not bear the name of the association, as is required by the rules of the House before gifts can be put on member’s desks.

The more serious rules of the House—those relating to members serving on committees and voting on bills where they might have a conflict of interest -- did not deter Parish either. He is an aggressive member of the House Committee on Agriculture and Natural Resources, the committee which must pass on all coal and agriculture bills. As one of two coal people on the committee, Parish helped keep the farmer-legislators from passing on sixteen of twenty strip mine regulation bills introduced in the last session of the General Assembly. And it was he who rose on the floor of the General Assembly to speak most vociferously on the one bill that did not get out of committee which would have, in any serious fashion, affected the strip mining industry. This bill, which would simply have stopped blasting on strip jobs at night so persons living nearby could sleep in peace and have limited the charge to protect the foundation of homes, went down to defeat after Parish said during debate, “If this bill doesn’t kill strip mining, I don’t know how it could be done.” Representative Omar Parish, Jr., has worked for Peabody Coal Company for several years as an explosives engineer and a truck driver.

□ Next to Parish, the representative most effective in halting strip mining legislation was Speaker pro tern Billy Paxton of Central City in Muhlenberg County. Paxton was also interim chairman of the joint legislative committee which wrote the only strip mining bill which passed both Houses during the Assembly’s 1972 biennial session; it merely made token changes. Paxton, an attorney, regularly denies that he works or has any special relationship with Peabody Coal. We found otherwise. C. C. McCall told us, “Bill Paxton represented Peabody on the negotiation on the road,” meaning a recent suit -- settled out of court - brought against Peabody for constructing a road to a strip mine without a permit. Another employee of the Division said the same thing, adding, “Peabody sure has been praising him.” Buddy Beach, the Division’s Acting Director, denied to us that Paxton had in any way been involved in the case.

We asked Paxton if McCall was correct, that he had been involved in settling the suit. “Oh, in a very minor way,” he said. Asked for further clarification, he said, “Yes, I was more or less along ... I made the appointment for them.” Paxton’s appointment was made for his former law partner, Dan Cornette, who is still Commonwealth Attorney of Muhlenberg County, and whose law firm regularly represents Peabody. Paxton was a member of the firm from 1960-1964. We asked Paxton if the Commonwealth Attorney -- the equivalent of a county prosecutor - should be involved in representing a company. His response, “So far as I know, it’s legal.”

Paxton denied that he had received a fee for making the appointment with the Division of Reclamation. He said that he was acquainted with Peabody officials to the point of, in his words, “playing golf with them in my backyard.” Paxton said he did not hunt, so he did not know anything about Peabody’s duck hunts for friendly officials. He did recall attending some Peabody parties “at River Queen and a similar situation at Sinclair,” two of Peabody mines. Paxton also said that he had met with Peabody Vice President Geissal “about the blasting bill. I was wanting to get their cooperation,” he said. (Paxton introduced a mild, compromise bill on blasting which passed the 1972 session. Introduction of a floor amendment to this bill to prohibit any blasting between the hours of 10:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m. brought Paxton to his teet to inform the House that any changes in his bill would force him to withdraw the whole thing.)

Paxton’s rise in the state legislature has been quick: having served only one term of two years, he was named Speaker pro tern in 1972 with the strong backing of the Ford administration—an administration whose pro-strip mining record is crystal clear. Rep. Marrs Allen of Pikeville, the chairman of the House Agriculture and Natural Resources Committee of which Peabody-employee Parrish is a member, and of which Paxton was chairman between sessions, attributed his success in bottling up all strip mining legislation in the last session to the “strong support of Governor Ford.”

Since the Kentucky General Assembly meets only every two years, the work of legislators like Parish and Paxton has given the giant two more years of very productive life, unhampered by state regulations except for those “enforced” by the present Division of Reclamation.

As the federal government moves toward a bill to regulate stripmining, it is the TVA and the Peabody Coal Company which are lobbying hardest for meaningless legislation. The right-wingers love Peabody and its parent, Kennecott; the liberals love TVA. Together, the two giants lead and protect the industry of strip mining at its vicious best. It all began in a little hollow in East Kentucky; another manifest destiny headed to destroy the West.

Tags

James Branscome

James Branscome is a free-lance writer from Sevierville, Tennessee, who contributes to The Mountain Eagle, The Washington Post and other publications on a wide variety of Appalchian topics. (1980)

Jim Branscome writes regularly on life in Applachia and is a staff member of Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee. (1974)