Out of Bounds: Frank McGuire and Basketball Politics in South Carolina

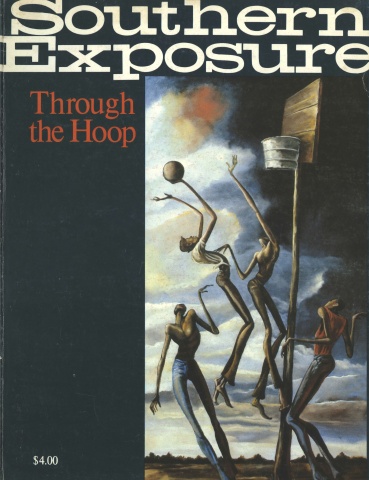

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

During University the summer of 1974, the University South Carolina lowered its mandatory faculty retirement age from 70 to 65. Several eminent professors filed suit in protest, but the university’s trustees implied that faculty members who reach age 65 are less competent than younger men and women. The issues at stake were hardly unusual for America in the 1970s. But an unseen figure in this case made it crucial not only for a few professors, but for thousands of Carolinians: Frank McGuire, the university’s legendary basketball coach, was approaching 65. He was not ready to retire, but his numerous political enemies wanted him out. “Everybody knew that Frank McGuire was inextricably tied to the case,’’ said the professors’ attorney. “You could hear the basketballs bouncing in the courtroom.”

In August, 1978, three months before McGuire’s 65th birthday, a decision was due at last from the state’s Supreme Court. The coach felt confident. After all, he had lifted the state and its university into national prominence as a center of championship basketball. South Carolinians praised him as their savior in the sports-conscious South, and they adored the way he and his teams bullied their way into the national limelight. But in building his basketball dynasty, McGuire stepped on many toes, and now his fate in South Carolina, a state known for patronage and political corruption, was not quite certain.

Frank McGuire was born in New York’s Greenwich Village on November 8, 1913, and grew up in the Irish-Italian ghettoes of lower Manhattan, the youngest of 13 children. His 6’4” father, Robert, was a traffic cop on the corner of Canal and West Streets for over 20 years; “Big Bob,” as he was called, died when little Frank was three years old. The McGuire clan was then headed by their sturdy, devout Irish Catholic mother, Anna. Her demands were simple: the children must attend church; wear hand-me-downs; listen to their oldest brother, Willie; and speak one at a time while seated at the crowded dinner table.

Young Frank was a handsome, broad-shouldered, tough guy. He was hot-tempered and athletic. His playmates on the street called him “Red” or “McGoo;” his high school newspaper nicknamed him “Elbows.” Like his friends, McGuire seemed headed for the West Side piers or, at best, a job with the New York Police Department.

When Red was out of school, or playing hooky, he spent hour upon hour at Greenwich House, a settlement home organized by turn-of-the-century social workers. There, under the tutelage of Ted Carroll — a tall, black Columbia University graduate — McGuire began to box and play basketball. He was well liked as a hard-nosed competitor who stood up for the underdog. By the time he was 18, McGuire had formed his basic stance toward life: it’s give and take, favors and returns; a guy has to know who his friends are and be loyal to them.

At St. John’s University in Brooklyn, McGuire captained the baseball and basketball teams under the legendary James “Buck” Freeman. A gutsy and aggressive competitor, McGuire was never afraid of firing a brush-back pitch or slugging it out with a rival center. On more than one occasion he marched into an adversary’s locker room offering to fight them on the spot because of their anti-Semitic smears against his teammates. “That wasn’t as bad,” he recalls, “as going back to my own neighborhood and explaining to my friends why I let those little Yids shoot all the time.”

After graduating from St. John’s in 1936, Frank played professional basketball for five seasons in the old American League, until a knee injury ended his career. When he wasn’t running up and down the floor, McGuire taught history and coached at his alma mater, Xavier Academy. He also worked as the greeter and bouncer at Julius’, a lower West Side bar and restaurant. If he could not handle a troublemaker, McGuire always knew someone else could. Trying once to calm a drunk heavyweight contender, Frank faced a tough battle.

“I could handle myself,” boasts McGuire, “but that guy was a pro. So I went to the phone and made a call. About five minutes later, three of the fellas from the docks came in and they whisper to this big bum, ‘Frank doesn’t want you here anymore.’ And he never came back.”

After he was dis¬ charged from the U.S. Navy in 1946, McGuire became the young head coach at St. John’s. Within three years, he was one of New York’s most celebrated heroes. He was dapper, handsome, quotable, and his teams won with alarming regularity.

By the early 1950s, Frank began to establish himself not only as a successful basketball coach, but as the kid who grew out of the ghetto. He was friends with politicians, entertainers, racketeers, policemen and priests. Harry Gotkin, one of his closest companions, says, “With Frank’s contacts, he could have made millions.” Yet all of McGuire’s energy and charm, all his amazing network of contacts from the Hudson River docks to the White House, were committed from the start to the politics of basketball and the creation of his own reputation. McGuire learned to talk and to listen with the ease of a ward boss and became one of the nation’s most popular after-dinner speakers. He could charm people when he needed to and threaten them when he had to.

In 1952 McGuire accepted the University of North Carolina’s challenge to lead their team to a level of parity with Everett Case’s fine N.C. State clubs. Within five short seasons, he brought an undefeated national championship to Chapel Hill, starting four New York City Catholics and a Jew. His real achievement was convincing Northeastern parents to let their sons spend four years in what they saw as the hot, oppressive, bigoted South. McGuire made the cover of Look Magazine and Sports Illustrated, was mentioned as a future candidate for governor and placed on everybody’s “Man of the Year” list.

Four years later, the charismatic and still controversial Irishman moved on to the big leagues. With the Philadelphia Warriors, he became the first coach to co-exist with the young, 7’2”, 290-pound Wilt Chamberlain. Frank, a master psychologist schooled in the streets of New York City, motivated his temperamental Goliath to average an incredible 50 points per game.

Meanwhile, the University of South Carolina hoopsters were suffering from a succession of mediocre coaches and miserable teams. Between 1953 and 1963, as a charter member of the Atlantic Coast Conference, the university’s basketball team compiled a 108-172 won-lost record. In 1963-64, USC’s Fighting Gamecocks were in the midst of a better than average 10-14 season. Unfortunately, Coach Chuck Noe suffered a nervous breakdown at mid-year and had to be replaced by Dwane Morrison, a 26-year-old assistant coach. More than a year before Noe’s collapse, however, the university’s hierarchy had already formed a “search committee,” made up of President Robert L. Sumwalt, Athletic Director Marvin Bass and influential State House Speaker Sol Blatt, Sr. Their objective was to lure Frank McGuire to Columbia.

The Blatts of Barnwell were one of South Carolina’s most powerful political families. In 1937, Sol had been elected Speaker of the House, an office he held for the next 25 years. Blatt proved an adept backroom politician, a persistent segregationist and an unwavering champion of fiscal conservatism. In a short time, everybody owed a favor to “Mr. Sol,” as he enjoyed being called, and Blatt knew exactly how and when to ask for its return. He called in many IOUs when he spearheaded a campaign to improve the reputation of the University of South Carolina, aided by his politician son, Sol Jr. Soon USC became Blatt’s special stepchild and the school’s athletic program his primary toy. At 83, victim of deafness and other medical problems, Blatt is now Speaker Emeritus — but he is still a member of the state house and with neighboring legislator Marion Gressette is considered one of the two most powerful members of the legislature.

In the early 1960s, Sol Blatt wanted Frank McGuire and the national acclaim he would bring the university. But McGuire was not certain he wanted to live in Columbia, or come to a “backward” school with a poor program. Blatt was persistent, and eventually swayed McGuire and his wife, in part tempting them with the advantages of South Carolina’s climate for their son, who had cerebral palsy.

On March 10, 1964, McGuire signed a five-year contract. The news came as a shock to the veterans of the East Coast sports world. “Frank McGuire at South Carolina,” recalls his long-time assistant coach Donnie Walsh, “would be like hearing John Wooden took the job at Mississippi State.” Nevertheless, the McGuires moved to the Deep South. Frank brought his old coach, Buck Freeman, with him, hired a young recruiter and called on his New York contacts to help locate players. His friends were glad to scout for him, but their job was tough, given the school’s facilities and reputation in academics and athletics. The only drawing card was McGuire himself.

The new coach faced one task even more difficult than recruiting: to generate interest and excitement in a community which understood little and cared less about his sport. Frank traveled across the state, urging civic and business groups to support his program. He sought out individuals to contribute to his new Tip-Off Club and to help his Northeastern players adjust to Southern culture. McGuire was the consummate politician: he remembered names, sent birthday cards, visited hospitals, raised money for charities and never forgot the Greek Easter or Jewish New Year. He told South Carolinians that they had been treated unfairly, maligned and laughed at; he promised to make them a winner and make Columbia “the basketball capitol of the world.”

Like a ward boss during an election, McGuire enlisted legions of loyal followers to cheer avidly for the boys and cry over their losses. Some South Carolinians remained hesitant over the school’s roundball future, but elsewhere expectations grew more quickly. People in North Carolina and New York had seen McGuire work his magic before.

Frank McGuire finished his first season at South Carolina with the worst season of his coaching career, but that spring he recruited one of the nation’s best high school players. Mike Grosso was a 6’9”, 225-pound all-around athlete from Raritan, New Jersey. He had sprinter’s speed, great strength and fine upper-body mobility. In the first round of his high school state championship, Mike scored 45 points and snared 43 rebounds!

The battle for Grosso was fierce. But Frank McGuire was the first coach to enter the Grossos’ lower-middle-class Italian home, and from that moment Mike hardly considered playing for anyone else. The South Carolina coach promised the family one thing — “I’ll take care of him” — and according to the youngster, “He was the only guy who never offered me money under the table.”

In late April, 1965, Mike made a special concession to the persistent coach at the University of Miami and agreed to visit the Coral Gables school. “When I got off the plane,” recalls Mike, “I was on television. Shoulder cameras were following me step by step; everywhere I looked there were pictures of me shooting a basketball. My name was on all the restaurants I went to. They said, ‘You want money, here’s money, go gamble on jai alai. Your parents can be flown down here. We have an airplane; anytime they want to come see a game, they can. You want a scholarship for your oldest brother to play football, you got it; your girlfriend a scholarship, you got it.’ They offered me $125 a week spending money, an expense account in a clothing store, a place on campus I’m supposed to have but an apartment off campus if I want. Hey, you know this was all in two days. When I left I told Hale, ‘Thank you very much, I saw your place, but I’m still going to South Carolina.’”

That was the beginning of Mike Grosso’s basketball career, and the start of Frank McGuire’s most painful defeat. McGuire’s first recruits, who entered South Carolina a year before Mike Grosso, were a gifted group. As sophomores (in their first year as varsity players under then-existing NCAA rules), they upset number-one-ranked Duke, topped Ivy League champion Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and gave NYU a run for their money at Madison Square Garden. It did not take an expert to realize that the next season, with the addition of Grosso, these same youths would dominate the league and possibly the entire country. Many coaches were alarmed.

Chief among those most concerned about McGuire’s new talent was Eddie Cameron, athletic director at Duke and a founder of the ACC. Cameron had worked hard to build the ACC into the most competitive basketball conference in the country. Ceremonies and tradition were important to Eddie; to McGuire, even the ACC tournament meant little. Once his North Carolina team was guaranteed a spot in the NCAA Eastern regionals and was scheduled to play N.C. State, then on NCAA probation, in the championship round. Frank rested his starters and played five subs. Cameron was irate. The two battled again when Duke signed Art Heyman, an All-American Long Island schoolboy McGuire thought he had locked up. And then one more time, when a UNC-Duke brawl resulted in the suspension of three players. Cameron accused McGuire of telling his squad ‘‘to get Heyman, that no-good Jew!” Frank especially resented the slander, since the leader of the fight was UNC’s Larry Brown, Jewish himself.

Cameron began his attack against McGuire and Grosso with an innocent observation: “I couldn’t understand how he (Grosso) could be admitted into USC and rejected by Duke when we are both in the same conference.” Though Grosso took the college entrance exams five times, he failed to achieve a combined score of at least 800 on his SATs — the minimum requirement for an ACC athletic grant-in-aid. Cameron obviously hoped Grosso would be disqualified, but under the ACC rules, he was eligible to compete as a non-scholarship athlete. Intent on playing for a man he trusted and idolized, Grosso passed up full scholarships from other schools and convinced his uncle to pay his tuition and expenses at USC.

In May, 1966, at the end of Mike’s freshman year, Eddie Cameron was still disturbed. He unsuccessfully urged the ACC to pass a new rule requiring that even non-scholarship performers score at least 800 on their entrance exams in order to participate in league games. Then, in early October, with Grosso practicing as the Gamecock’s starting center, Cameron pulled out his last trump. He called for another ACC executive committee meeting.

“We have seen where Grosso lives in New Jersey,” he told reporters, “and we don’t think circumstances indicate that the family can pay the bills.” It was then revealed that indeed his parents had not paid for their son’s college education, and that his uncle, who did pay, unwittingly used a check from his place of business, The Grosso Bar & Grill. Cameron, along with UNC athletic director Chuck Erickson, immediately accused Grosso of illegally accepting finances from a corporation.

On October 29, after a closed session, the ACC executive committee declared Mike Grosso ineligible. McGuire was furious and had to be physically restrained from attacking a committee member. He announced that he would appeal and that he intended to play Mike in spite of the ACC’s ruling. He charged his adversaries with conducting a personal vendetta against him at the expense of a 19-year-old youth: “They are discriminating against this boy. There are so many other players in the conference with scores lower than Mike’s and they are playing.”

Mike Grosso, bewildered, continued to work out with the team and tried to keep up with his studies. But at a late November scrimmage, one week before the Gamecocks were scheduled to open their regular season, Grosso tore his knee. He was operated on in mid-December.

From then on the situation only got worse for McGuire. One week before Christmas, conference officials approved new legislation granting all members the right to cancel games with USC if they considered such contests “inadvisable.” One day later, Duke announced it would not play basketball with South Carolina. The six other institutions decided to honor their commitments. Paul Dietzel, South Carolina’s newly hired athletic director and football coach, accepted the ACC position, which infuriated McGuire. Dietzel called the Duke decision “regrettable,” but said he understood they were “within their rights.”

On January 9, 1967, a 23-man board of the NCAA met in Houston, Texas, and cited USC for one infraction involving academic standards and three dealing with financial aid. The school was prohibited from playing in post-season tournaments and from appearing on a television network sanctioned by the NCAA. And Mike Grosso was declared ineligible to play basketball at South Carolina. Grosso eventually enrolled at Louisville University. Once again he damaged his knee; it never healed properly. “Basketball was never the same anyway,” reflects Mike. “I’d look over to the bench and big Frank wasn’t there.”

McGuire was embittered, angry and helpless. He viewed the entire episode as a vendetta by “weaker men” who were jealous of him. He called Eddie Cameron “a skunk” and in private he blasted Dietzel for not supporting the basketball program. Petitions cropped up throughout the state for the university to withdraw from the conference, but McGuire asked that they be discarded.

University of South Carolina officials had hired Paul Dietzel as their new football coach and athletic director in the midst of the Grosso affair. At one time Dietzel had the brightest future of any gridiron coach in America. When still in his mid-30s, he had led the LSU Tigers to a national championship. He was a man of precision, organization and assertiveness, with a mind for detail and a glib tongue. Dietzel had dubbed his stalwart Tiger defense “the Chinese Bandits,” and the following season every protective 11 from the Pop Warner League to the NFL had its own clever nickname.

Columbians were ecstatic about having Dietzel and McGuire on their side — two men who had been to the top.' The morning after Dietzel signed his lucrative contract, a picture appeared in the Columbia State depicting the two national celebrities beaming and clasping their arms. The caption read, “Two Old Friends Reunited.” But when Dietzel moved McGuire’s offices from the Roundhouse complex to the dingy trailer outside the Field House, the brief honeymoon was over.

Frank did not know about Dietzel’s secret contract demands: three columns of requests with 11 listings in each, as if he was already planning for his offense, defense and special teams; one included McGuire’s removal as associate athletic director. Dietzel received whatever he asked for, down to “the right of Anne to use the University’s airplane.” (To this, however, President Jones had appended, “Yes, providing Anne is his wife.”) When McGuire later voiced his dissatisfaction with Dietzel’s attitude toward Grosso, the new athletic director had Jones write him a letter of censure. It read, “The impression must not be given to friends, alumni, or the public that there is friction and strife within the department, the University, or the Conference.”

McGuire refused to have anything to do with Dietzel; he decided to concentrate on rebuilding his already once-rebuilt program. Winning proved to be the prescription that would satisfy Columbia’s sports enthusiasts together with Blatt’s multimillion-dollar, 12,700-seat arena to replace the school’s small and dilapidated field house.

The USC quintet was built around four sophomores and a junior (John Roche, Billy Walsh, Tom Owens, John Ribock and Bobby Cremins) who soon captured the heart of every Gamecock fan. The experts picked the 1968-69 team to finish sixth in the conference, but by the end of the regular season they were rated eighth in the country. The inexperienced group won 21 of 28 games, defeated national powerhouses North Carolina, Duke and LaSalle and went to the NIT. Roche was voted the ACC’s Player of the Year and McGuire, the league’s outstanding coach.

The young Gamecocks romped through the 1969-70 regular ACC season undefeated, only the third team in conference history to accomplish such a feat. (McGuire’s Tar Heels in 1957 and Duke’s 1963 club were the others.) Even in victory, Frank and his hoopsters remained arrogant and never refrained from hurling thrown objects back at the crowd or answering a heckler. They infuriated ACC fans and officials when, after a loss to N.C. State in the tournament finals, they refused to accept their runner-up trophies. Cameron was again steaming, but McGuire was boiling mad: “I wouldn’t shake that skunk’s hand anyway.”

During the 1970 and 1971 seasons, McGuire’s teams were among the nation’s best, winning 48 games and losing only nine. Though they never won the national championship, as some sports magazines predicted they would, fan interest remained strong. Columbians idolized McGuire and his New York imports. Backboards sprouted in the yards of private homes, jerseys with Roche’s familiar number 11 were sold out in every sporting goods store, and youngsters stood at the foul line crossing themselves as their Catholic heroes had done. Each player had at least one fan club, the governor began to meet recruits, and portraits of the imported athletes appeared like mushrooms on the walls of local lounges. McGuire was given a television show, a weekly newspaper column and the rights to use university facilities for his summer basketball camps. “McGuire for Governor” bumper stickers and “McGuire Power” buttons were all over town.

Frank was easily the most popular man in the university and state; even in defeat, his supporters were devoted to him. Blue-collar folk loved his outspokenness and independence. Once, in a game at Clemson, McGuire was hit with thrown objects, had his seat pulled from under him and was taunted by a heckler’s chant of “Your wife is dead, your wife is dead.” When the contest was over, Frank challenged any of the loudmouths, who were mostly football players, to fight him. He had no takers, but he was still scheduled to appear on announcer Bob Fulton’s post-game show. “At least 500 Clemson fans circled around us,” recalls Fulton. “All of them were waiting to hear what Frank had to say. They were silent, and he was incredible. Frank said exactly what was on his mind. He was fearless.” The affluent also loved McGuire. He was a celebrity, a gentleman who had paid his dues and delivered. Frank would drink, dine and occasionally play golf with some of his new supporters. He admired their fortunes; they thirsted for his fame.

Meanwhile, Dietzel, distraught over his own inability to recruit “top-notch athletes” under existing academic guidelines, convinced the Blatts, President Jones and the board of trustees to secede from the ACC. McGuire acquiesced. Going along with Dietzel’s plan would prove to be a significant political error. However, Frank felt sure his program would continue to prosper regardless of the school’s affiliation. In addition, he looked forward to more peaceful days outside the ACC. Secession was not a new concept in South Carolina. Time proved McGuire and Dietzel wrong. The latter could not win no matter how many blue-chip athletes he recruited, and though McGuire’s teams continued to win, produce All-Americans, play a nationally representative schedule and go to post-season tournaments, basketball fervor subsided. Local fans loved the frenetic atmosphere surrounding ACC games. The new schedule, which omitted neighboring rivals, did not afford them the same release. McGuire’s recruiting was also damaged because opposing coaches would convince high school stars of the ACC’s merits (fantastic media exposure, community support and better competition). Frank became an outsider looking in, and in spite of his team’s top-10 performances, attendance declined every single year. In 1975, when McGuire’s quintet failed to win 20 games for the first time in seven years, he began to lobby actively for re-entry into the ACC.

Soon Frank McGuire was being criticized by people who had previously been devoted to him — in particular, the Blatts. In order to please them, Frank committed a second political mistake. In July, 1975, he appointed Greg Blatt, Mr. Sol’s grandson, to his staff.

Greg Blatt, then in his mid-20s, had been a non-scholarship performer on one of Buck Freeman’s freshman squads, later served as the varsity’s team manager and then coached for two years at a small rural high school. McGuire chose Greg over more qualified applicants (former Gamecock players Bob Carver, Jimmy Powell, Jim Walsh and George Felton), rationalizing he would not have to worry about losing Blatt’s support.

Greg’s role, though, was less than interesting to the young man. With two expert tacticians in Donnie Walsh and Ben Jobe — a black former head coach at three universities — McGuire relegated Blatt to scouting and recruiting. The Blatts resented the fact that Greg was not more involved, but Frank had absolutely no intention of using him other than as “a road man,” the usual position for a young coach. Friction began to develop within the USC basketball office.

Meanwhile, a hunt was underway to find a replacement for Paul Dietzel, who had been pressured into resigning by the school’s trustees. Any new mentor would need a record of winning regularly on Saturday and going to church regularly on Sunday. Most of all, he would have to be approved of by the Blatts. After several candidates declined or were discarded, the board’s search committee proposed Jim Carlen, the head man at Texas Tech, a successful builder, good teacher, organizer, talker and Christian. Carlen was a proven winner plagued with his own inter-departmental troubles at the Southwestern Conference school. He agreed to accept the job, if he would be named athletic director as well. Since the Blatts did not think McGuire would make a very good athletic director, Carlen got the job.

As soon as he moved to Columbia with his loyal Texas Tech staff, Carlen began making changes in the university’s athletic department. He fired the veteran sports information director and hired a new business manager to oversee the department’s finances. McGuire hungered for the ACC, but when Coach Jim led his first USC football team to a 7-5 record and an invitation to the Tangerine Bowl, permanent independence seemed a real possibility. Since McGuire was also disappointed that he had not been named athletic director, friction increased. The two men soon refused to speak to one another unless confined to a conference room.

Finances became another source of mounting tension. After the first gridiron season, Carlen gave raises to all football assistant coaches but none to roundballers. Later, McGuire and his assistant coach, Donnie Walsh, were called before the board of trustees “to explain certain unnecessary items” on their expense accounts; they fumed and blamed Carlen. Frank faced accusations that he had incurred lavish expenses in on-the-road recruiting and was asked to justify even minor notations for liquor, food and hotel accommodations. Though they refuted every charge, Walsh and McGuire were struggling against a new alliance: Sol Blatt, Sr., board chairman T. Eston Marchant, influential trustee Michael J. Mungo and Jim Carlen.

The Blatt-McGuire feud raged into an open conflict during the early months of 1977. At a Gamecock Club banquet, held to honor the school’s new president, Dr. James T. Holderman, Mr. Sol, the guest speaker, praised all the athletic mentors who were present except Frank McGuire. The basketball coach sneered at the old man and whispered, “I’ll get you for that!” Later Blatt apologized to McGuire, claiming he was old and forgetful. In private, he said it was because he had drunk one too many, but the damage was done.

By the time the 1976-77 season was about to begin, Frank McGuire was unsure about his tenure at the university. Frank’s squad was inexperienced and erratic, his worst in over a decade. In addition, the USC hoopsters played one of the nation’s toughest schedules, meeting nationally ranked Alabama, Kentucky, Michigan, Marquette and Notre Dame. The fans were anxious, as were the trustees, and McGuire needed to find another winning formula — fast.

In early February, while the Gamecocks were struggling with a break-even record, McGuire discovered he was on the verge of capturing a landmark 500th career victory, a feat shared by only a handful of coaches. McGuire lost little opportunity in turning the achievement into a mammoth celebration — just the spark the sagging season needed. In February, McGuire also became the third active coach in basketball history to be elected to the Hall of Fame. South Carolina’s coach had become “a living legend.” Celebrities from a myriad of professions came to Columbia to honor McGuire at a black-tie banquet. Priests, writers, cops, jocks, longshoremen, politicians and matinee idols stood to applaud their trusted friend. The Gamecocks finished the season with a 14-13 record, but it was their coach’s year. By an overwhelming majority, the state legislature voted to name Carolina Coliseum after the man who built it, Frank McGuire.

The Blatts, Marchant and Carlen obviously could not force McGuire out at this moment. Instead, they worked silently to undermine his position. When Frank went to Springfield, Massachusetts, to attend the Hall of Fame ceremonies, not a single USC official or Carolina notable appeared at the event or even sent a message. “That was lousy and painful,” remarked Donnie Walsh. “We used to hate Dietzel, but when he went to a bowl game we sent him a telegram.”

When he returned to Columbia, Frank was confronted with more bad news. The board of trustees had tabled the motion to rename the Coliseum after him, claiming that the school’s faculty would not accept the change. The board did, however, consent to name the arena after McGuire. “Isn’t that ridiculous,” Frank quipped. “Did they name the pool or the whole physical education center after Sol Blatt?”

Prior to the start of the 1977-78 season, as McGuire was approaching his 65th year, the roof caved in. Donnie Walsh left to take the assistant coaching job with the NBA’s Denver Nuggets. Walsh had been a devoted friend and confidant, and it was assumed that he would succeed Frank whenever the head man retired. Yet Donnie knew the trustees would never hire another New Yorker, especially one who had acted as McGuire’s mouthpiece. “When I left,” said Walsh, “I told the press I had not been assured I would get the job; what I didn’t tell them was that I had been assured I wouldn’t get it.”

Then Greg Blatt surprised everybody by taking an assistant’s position at the Citadel in Charleston. Two days later, university president Holderman announced Frank would become athletic director in charge of USC’s regional campuses and would be expected to assume these duties immediately after the basketball season. It was the proverbial boot upstairs. Publicly, McGuire shouted that he was not ready to retire; in private, he berated Holderman for “selling out” to the Blatts. Frank wanted to coach for at least two more seasons; his opponents, however, asserted they were doing him a favor, since the university’s new mandatory retirement age was 65 and Frank was 64. “Let the courts decide that,” Frank countered.

Lacking the support of large contributors, USC’s board of trustees, president md athletic director, and the Blatts, McGuire had to appeal to his grassroots constituents to maintain his position. The day after Holderman’s offer, the press flooded into McGuire’s office. Hurt and dismayed, Frank informed them it was the bigwigs against him. He claimed it was not a coincidence that after young Blatt departed the bomb had finally exploded. “How can I compete against Carlen?” he asked. “The guy has access to the president, the trustees and the school’s business manager.”

McGuire was tired of defending his integrity in front of the trustees, and he chose the football team’s forthcoming trip to Hawaii as ammunition in his counterattack. “Do you know why he’s got these people in his corner?” Frank quizzed reporters. “Because he can afford to take them all to Hawaii for free, and what the hell can we do — take em to Buffalo?” A McGuire aide concurred and said, “Even the school’s cheerleaders have to pay to go to Hawaii, but the board members and other school officials go for free.” McGuire then asked another question: “Do you think some of these old Southern leaders are worried about having Ben Jobe, a black, so close to the top?”

It was a brilliant performance by an old ward politician. McGuire instantly won the media and the public to his corner. Few people relished the idea of one family running the state university, and the black community, which previously had paid little attention to USC athletics, was also compelled to stick up for Frank and Ben Jobe. “God Bless McGuire” stickers appeared, and a group of wealthy Tip-Off Club members took out full-page ads in the state’s newspapers seeking signatures and contributions for their Save McGuire movement. The response was overwhelming. Former players, friends and associates called to offer whatever support they could. Though still worried, and aware his recruiting for the next season was torn to shreds, Frank grew more and more confident. He was angry, but his constituents were even more irate. Frank McGuire had treated them fairly. He had delivered, and whenever he wanted to step down was good enough for them.

The battle moved into the 1977-78 season. Carlen suddenly found himself on the defensive. His recruitment of Steve Swinehardt, a highly touted Ohio schoolboy, came under an NCAA probe. Meanwhile, McGuire’s support steadily solidified. At one home game, fans honored Frank with an Appreciation Night ceremony with the theme, “If you support the Irishman, then wear green.” Few looked as verdant as USC President Holderman. Whatever his feelings about big-time athletics, the resourceful university head had recognized his tactical error immediately after the regional campus offer was made public.

Meanwhile, Carlen refrained from making any public anti-McGuire statements, but he did try to bolster his own position. Investigators cleared him of any wrongdoing in the Swinehardt affair. He boosted his standing with the trustees by donating over $200,000 from his athletic department’s profits to the academic wing of the university. And he donated to charity the proceeds from a well-publicized Hollywood-style “Roast” given by admirers, including Gerald Ford.

While the 1977-78 basketball season narrowed to its final weeks, Holderman announced the appointment of Dr. James Morris to the newly created position of Vice President of Athletic Affairs. Morris was an old friend of McGuire. The move prompted Carlen to contemplate a possible law suit against the university since he felt Morris’ vaguely defined duties would usurp his own authority.

When the regular season ended, McGuire was a smiling Irishman and a self-assured political victor. His quintet surprised everybody and finished with a 16-11 record, good enough for an NIT bid. Meanwhile, Carlen was becoming embroiled in a series of embarrassing financial controversies: two men who were contracted by his department to own and operate the food concessions at USC football and baseball games were convicted of embezzling $95,000; a state Law Enforcement Division audit showed that $17,000 in cash was missing from the past season’s gridiron receipts; and a North Carolina travel agency filed a suit against the Gamecock Club for breach of contract concerning the football team’s Hawaiian excursion.

By the summer of 1978, it seemed everybody but Frank McGuire was tainted. Sol Blatt, Sr., had lost much of his colleagues’ respect because of his active role in the dump-McGuire movement, as well as his involvement in a scandalous argument within the state legislature over the status of his female House Clerk. Holderman’s indecision in the lengthy athletic department feud tarnished his image. Carlen, about to direct the least successful Carolina football campaign in five years, was judged too abrasive by the Columbia press. The board of trustees, as the fans saw them, were a group of men who turned their backs on the one individual who brought a sense of pride to the state.

Try as he might, there was simply nothing Sol Blatt, Sr., could do to get rid of Frank McGuire. One moment the Speaker Emeritus would ramble on about how bringing McGuire to USC was “the biggest mistake I ever made,” but seconds later he would proclaim, “I want to be friends with him, I want to be Frank McGuire’s friend.”

In August, 1978, the State Supreme Court ruled that the University of South Carolina must comply with the state’s mandatory retirement age of 70. Basketball coach and old ward politician Frank McGuire had five more years at the helm. “I’m the only guy they tried to get rid of and couldn’t,” remarked McGuire.

Frank McGuire had remembered his boyhood lessons of survival. Although he had proven once again that he was a remarkable in-fighter and had saved his own position, Gamecock basketball was again floundering. The coalition of strong ballplayers, loyal fans and friendly state officials that ward boss McGuire had built up so diligently over more than a decade could never be the same.

Tags

Daniel Klores

Dan Klores is a freelance writer living in Columbia, South Carolina. His book, Roundball Culture: South Carolina Basketball, 1963-1978, will be published this fall. (1979)