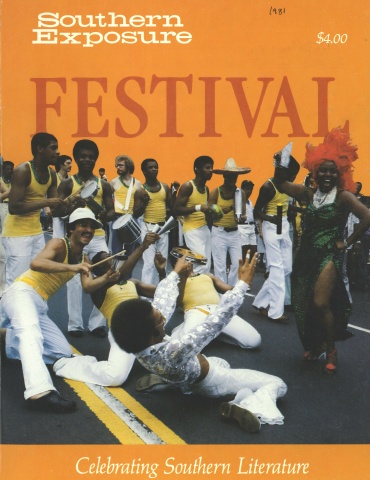

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

Augusts we’d go south to Mississippi

into sickening, stifling heat

each summer to see strangers

from a past my daddy seldom speaks of:

to the grandmother he saw outlive his mother,

to the cousins he grew up with,

to aunts whose husbands no one ever mentions.

They lived, all six sisters,

in the town where they were born.

They came each year to see us

in the home they built again

after the fire, before the Great War:

Aunt Emma’s house

at the end of Seelbinder Road.

From the summer I was nine

until I was fourteen,

I recorded it all

with my Brownie Hawkeye:

my brother on the porch swing,

no hair to hide his ears;

my sister, pixie faced and silly in her jumpsuit:

baby Venus on a myrtle stump;

the obligatory family portrait on the steps:

Aunt Emma, Mama, Daddy, Henry, Betty, me.

Now, ten years later, we go again,

this time in June,

but it is hotter than I remember.

My glasses steam when I step outside.

No one stirs from noon to three.

One sister is dead and another soon will follow.

I go now a woman grown and single,

a foreign red-head still gangly.

Never a beauty, I hear them thinking.

Not even a Methodist.

If this is a reunion, it’s not official.

We are relations seldom seen.

That alone is an event.

I hear again my mother’s warnings to behave.

I am lost for conversation.

All we share is blood and marriage.

In ten years Emma has not changed.

She studies me across the room.

“You young people like to look at pictures,”

she says. “I have some pictures there.

Bring them here.”

I bring three books of photographs and clippings,

collections begun when photographs were rare and serious.

We turn page over page of firm-set faces,

forms in heavy clothes and shoes

seated or standing against studio backdrops

or brown landscapes and clapboard houses.

Here is my grandfather.

This is Zeda Musselwaite.

That was a winter hog-killing.

Here is my father with his cousins.

This is the school. These are friends,

a picnic by the river,

a niece in Meridian.

“He’s dead,” she says.

“She died last year.”

“She’s in a nursing home over in Greenwood.”

“He died the year I married.”

“I never hear from her anymore . . .

I guess she’s dead by now.”

“These pictures mean nothing to me.”

She says it more than once.

“All my friends are dead or dying.”

In our search for roots, Emma, we cling

to photographs of women.

We young people love to look at pictures.

I look for signs in my grandmother’s face:

for the features I have gained from her,

for some evidence of the woman

whose spirit and desires

I am told I possess.

I look for younger, smoother faces

than those before me now,

for the same light in the eyes,

that same smile or turn of chin.

I look sometimes to see myself old.

How will I age, I wonder.

Will I gain a girth or another chin?

Will my hair salt gracefully?

And this — this photograph of two women

standing on winter ground

before the trellis of this house we sit in now,

standing in heavy dresses and highbutton shoes,

each with an arm encircling her friend’s waist,

drawing her close enough for hips to touch,

each tilting her head toward a waiting shoulder,

each looking into the camera as if to say,

Capture this moment. This is my friend.

I want to remember her always.

On it, in your hand, I read,

“Ophelia Emma 1912”

There was some cause for this photograph.

Was it a parting or a birthday?

In three books I have seen no other likeness ofthis woman

whose impish smile dares the camera here:

“You cannot take this woman from me.

We shall share the frame forever.”

I want to know more of this.

I hand you this memory and ask.

You shrug. “Oh, that’s Ophelia.”

Your tone says ask no more.

Later, when the house is full of relations,

I find you in a corner alone,

out of the hub of reunion jokes and stories,

and I ask again.

Who was Ophelia?

“She was my best friend.

We were in school together.

She was a born artist.

She could draw anything.”

Your eyes have gone a distance I can’t reach.

“She died. In 1917.”

And then, as if you put it there yesterday,

you reach, without rising, behind you to a desk,

open the second drawer,

take out pages from a writing tablet.

Pages on which one friend

copied for another

a favorite poem,

illuminated it from her heart,

gave it as a keepsake.

I hold now in my hand

a memory outlasting photographs,

stored here for over sixty years.