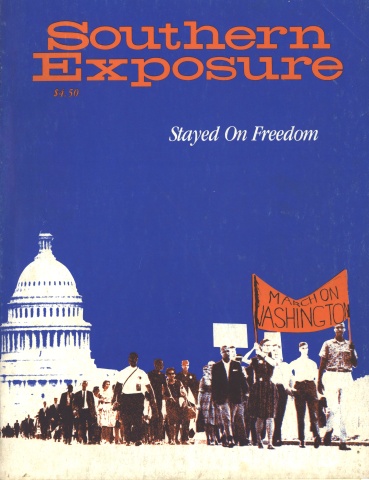

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

The most significant feature of any movement that is effecting profound change in society is the role it plays in creating a dual authority in the country. It is the authority of the movement as the people’s response to the policies of the established authority which gives the movement the power to ultimately effect a democratic transformation of society.

Beginning with the events of Montgomery in 1955, when the Afro-American community of 50,000 citizens stood as one in a bus boycott, and extending to 1969 with the Vietnam Moratorium, in which an estimated four million people participated, our Movement created a dual authority in the country. There was on the one hand the established authority: the citadels of institutional racism, the masters of war, the apparatus of government — state, local and federal — and those chosen to do the dirty work of suppressing our Movement in defense of the status quo. This established authority acted out a way of life that was rooted in custom and tradition, and dictated by class interests.

The other center of authority was the Civil Rights-Anti- War Movement which represented a continuum of protest activity during the period. This authority, the Movement, represented the people’s alternative to the power of institutional racism and colonialist war. The Movement had at its disposal such resources as dedicated organizers who educated and mobilized the aggrieved people; charismatic, grassroots leadership that articulated the goals and the vision that inspired action; performing artists who gave of their time and talent; church choirs, benefit concerts, mass meetings, and literature designed to instruct and enlighten as 6 well as reflect the experiences of the Movement. All of this was held together by an ethos of camaraderie developed in struggle.

The Movement was a proliferation of centers busy with community activists planning strategy, recruiting volunteers, raising bail for those arrested for exercising their constitutional right to protest injustices; above all, people organized and aroused to action. In this many-sided collective activity, untold numbers of people made personal decisions on how much they would allow the Movement’s authority to affect their everyday lives. The decisions were varied: whether to attend a meeting, participate in a march, or register to vote; whether to use vacation time, or drop out of school, to do full-time organizing; whether to give the family car to the Movement or put up property as bail bond. Some ministers cut down on their church work in order to do what they perceived in a new light as the work of the church. Teachers volunteered to run “freedom schools,” and a few lawyers donated their services to defend participants in the Movement or to help redefine the meaning of law-and-order in the South.

In the years between Montgomery and the Vietnam Moratorium, the authority of the people’s Movement in this country was expressed in thousands of individual actions and hundreds of local demonstrations in cities across the land where citizens singled out targets for disciplined, collective action. The authority of this Movement sprang from the best traditions of the Negro church, organized labor and populist radicalism, and its spirit was reflected and continually revived in the musical themes of that period: “This Little Light of Mine,” “All We Are Saying Is Give Peace A Chance,” “We Shall Not Be Moved,” and the most famous, “We Shall Overcome.”

Obviously, the struggle for civil rights did not begin with the mass protests of the 1950s, but the physical involvement of thousands of Afro-Americans and whites in the South and North transformed the struggle into a movement whose authority challenged the basis of the established order’s value system with a new vision of freedom, brotherhood and democracy. It was this spirit and commitment to a new set of goals and values that enabled our Movement to sustain the wounds inflicted upon peaceful demonstrators in Birmingham and Selma, the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and the Poor People’s encampment in Washington, DC.

From an international perspective, the mass movement of the 1950s and ’60s created a moral and political crisis for the rulers of the U.S. who at the time were immodestly proclaiming themselves the “leadership of the Free World.” One would have had to look very hard to find a country whose citizens were so systematically denied the elementary right to use a public park or go into a restaurant for a meal or use the regular elevator or attend a public tax-supported college. In the United States, Afro-Americans were denied every one of these rights and more. By forcing an end to such embarrassingly backward practices, the Movement created the conditions whereby the U.S. and its leadership partially closed the gap in relation to the rest of the modern world.

Similarly, through the sacrifice of the Movement, through the emancipation of the mind and spirit of the South’s people, the Southern region of the United States rejoined the nation and entered fully into the twentieth century. Segregation had clouded the white Southerners’ perception of reality and held them back from acting on what they did perceive clearly. The Civil Rights Movement, like all mass movements for democracy, was a great teacher of civilized values, and in the wake of the removal of segregation, the common interest of the white and black working population is beginning to surface, as exemplified by union organizing efforts in the region.

Given its particular focus, the Civil Rights Movement achieved its stated objectives by first abolishing law-enforced segregation and ending disfranchisement of the black population in the South. Having achieved these objectives, the movement for civil rights was transformed into a movement to complete the tasks of the Second Reconstruction by winning greater representation for the black population in government. When the civil-rights legislation in 1964-65 became law, there were barely 300 black elected officials in the country. Today, there are almost 5,000 — about half of them in the South. When the civil-rights legislation of 1964-65 was passed, there were a million-anda- half black voters in the South. Today there are nearly three million. It is important to understand that this transformation from mass protest to a focus on legislative power was a logical development, since our experience had taught us that having a greater voice in the institutions of government is the only way to protect the rights we have won and make secure their enforcement.

It is equally important to recognize that the civil-rights laws of the 1960s were passed after the fact. They did not create change; rather the struggle for expanded democracy, participated in by tens of thousands of our fellow citizens, produced a body of legislation which confirmed the effectiveness of that struggle. The laws were a crystallized form of expressing the new reality that people would no longer abide by the rules and mores of racial segregation. Segregation was in fact abolished by the power of the Civil Rights Movement. A movement, whether of reform or revolution, always struggles for a legislative manifestation of its victory because that establishes a new code of conduct in relation to the old order of things. It confirms that change has been accepted and that the particular struggle for democracy has been victorious.

Once the victory is formalized, the movement must regroup around the definition of the next stage of mass democracy and move on to its fulfillment. The opposition will inevitably attempt to trap the movement into preoccupying itself with implementing victories that have been codified into law. Indeed, the law is often written in such a way as to encourage this entrapment. And since the Movement’s activists are often experiencing a degree of exhaustion, the tendency to focus on emphasizing that which has been won is even stronger because it is a form of reprieve.

The decade of the 1970s has found the Movement caught up in just such an eddy in which motion is devoid of clear direction; we have become preoccupied by the rituals of the technician-intelligentsia and have shifted responsibility for social change to them, substituting their busy-ness for mass-movement organizing. Yet only the latter can provide the driving force for the achievement of greater democracy. The tendency has become to make Title III, VI or IX of this or that act the focus of our attention along with the writing of proposals to foundations or government agencies. These activities have been projected as “more sophisticated” ways of achieving our objectives. This is the New Thing; and the complexities of life and the difficulty of identifying programatically what we need to focus on have tended to give credence to this new style.

It is inevitable and good that we have learned — for example — how to hold press conferences, for we all recognize that technologically this is a media age. But it was disastrous for us to rely primarily upon these corporate forms of mass communication to get our message and analysis out to the public. Once that dependence becomes a matter of style, it is too easy to fall into the practice of tailoring activity to fit what the media might pick up. Such dependence encourages competition among the leaders themselves since the new value system becomes who gets the most media attention. In the end, it means a new kind of addiction to media rather than being in charge of our own agenda and relying upon mass support as our guarantee that ultimately the news-covering apparatus must give recognition to our authority.

The mass meetings held every Monday night, week after week, in dozens of Southern communities and every Saturday morning in Northern cities during the early 1960s were main forms of communication, mass education and mass mobilization. This was the strength of the Movement: not having fallen into reliance upon the monopoly-controlled media to report its activities. Through these regular mass meetings and the mobilization that followed, the direct participation of the community in the struggle to secure our objectives was sustained. Thus a direct line of accountability was maintained between the leaders at all levels and the broad base of support among the people. Another important dimension of this relationship was that the people themselves financed such a movement, lessening the dependence on the “generosity” of other sources of revenue. The power of any movement for democracy is always dependent on such reciprocal relations between the mass of people and their leadership.

The decade of the 1970s has been a hard teacher for Afro-American leaders, and the sense of apprehension and doubt about the possibilities of a better life under this economy has dramatically increased. Yet the remedies traditional civil-rights organizations are clinging to and placing hope in are at best potentially relief measures rather than solutions. Such measures as economic set-asides from the federal budget to assist black businesses are seen as an aid to economic development; more affirmative action, vigorously enforced in both the public and private sector, and more support to black colleges are of course all laudable relief measures that deserve support. However such programs suggest that we are suffering from a parochial approach to solving the problems of the Afro-American community. These problems are connected to and are an exaggerated expression of a deeper malady. The United States is a society currently in the throes of a long-term economic crisis whose process of ruination is a protracted one. Notwithstanding the appearance of relative prosperity among a large section of the employed population, the features of stagnation and dislocation in our capitalist economy are deep and of long duration. The time in history in which we live, and the general crisis and regressive trends in our country, call us to move boldly on to the next stage of struggle for mass democracy.

The Civil Rights Movement of the ’50s and ’60s was always an anti-racist revolt within the general struggle to preserve constitutional rights and block the timetable of fascism in our country; the latter is the natural tendency of the ruling corporate elite when their system is in the kind of crisis it is today. Yet this mass-movement revolt against racism in all its forms was not an anti-capitalist revolt, nor was anti-capitalist ideology at any time a very significant influence. However, the Civil Rights Movement under the leadership of Martin Luther King, Jr., evolved the strategic concept of mobilizing the poorest among the working class in a campaign to dramatize the issue of widespread poverty in the “richest country in the world.” At that point, the Movement began to step across the threshold of struggle for merely formal equality into an era of struggle for substantial equality. This jump inevitably meant a confrontation with the economic and ethical deficiencies of the free enterprise system itself. The very essence of the Poor People’s Campaign was to confront the nature of the system that produces poverty for the millions as a natural accompaniment to making the super-rich more extravagantly wealthy. On the eve of that campaign, Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis as he responded to the call for help from sanitation workers seeking recognition for their union and their right to collective bargaining.

The voices of the New Right are frequently heard today proclaiming that “the movements of the ’60s went too far.” In fact, our social protest movement didn’t go far enough in the depth of its criticism and public education concerning the nature of American institutions. Nor could it have gone further, for once the Civil Rights Movement correctly shifted its focus to the poverty conditions of millions of our fellow citizens and to the immoral, racist war in Vietnam, the Movement became the target of a counteroffensive spearheaded by the government. Many of the details of this sinister counterrevolutionary offensive were officially documented by the Senate Select Committee headed by Senator Frank Church and are now public knowledge. So we need not elaborate here on COINTELPRO, political assassination and other forms this took. What must be underscored, however, is that the design was to bring to a halt the advances and the momentum of the movements of the ’60s; to get the Movement out of the streets and therefore out of public view and out of public consciousness; to break up the alliances that were being built with organized labor, women, Latinos and Native Americans and otherwise liquidate the Movement. That was the point. This was a more sophisticated attack than those which occurred during the crude illegalities of the early McCarthy era, but the content and purpose were the same. The crowning achievement of this counterrevolutionary offensive was the election of Richard Nixon to the presidency of the United States, and as a consequence, this marked the beginning of the nadir of this historical phase of the Civil Rights Movement.

The Movement is still alive, yet its life today is being consumed fighting defensive battles. The defense of affirmative action programs in education and employment; the defense against retrenchment by some states whose legislatures are trying to rescind their decision to endorse the Equal Rights Amendment; the defense of innocents in prison like the Wilmington Ten and the Wounded Knee defendants are among such examples. No one can deny that defensive battles have to be fought from time to time and fought effectively so that victories are won. Yet the time-tested wisdom which holds that the best defense is an offensive movement is an important concept for us to renew in practice today.

Social change and real progress always require that a movement keep the offensive in pursuit of clearly defined goals. That is how our Movement abolished segregation in public accommodations; it launched a mass offensive against this form of institutional racism. Defensive battles are selectively taken up and victories won when they are shown to be related to the offensive our Movement is developing. Otherwise, we can be kept busy by the opposition with defensive battles, but we will not be going anywhere. In such a busy-ness situation, the vision of our goal is lost and soon the movement fragments.

To put our Movement on the offensive again, we must make the transition from a primary emphasis on formal civil rights to an emphasis on achieving the goal of substantive civil equality. Such a movement will shift from a focus on the formal recognition of our rights to the implementation of actual equality in the conditions of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness all of us aspire to share. It will provide our country with a national purpose and goals consistent with human progress. It will be good for the spiritual and material well-being of U.S. society, and as a majority of the population embraces and gets involved in this national effort, our country will again “catch up” with the global movement for human rights that daily exposes the backwardness and contradictions of our present system. Consider these fundamental structural inequities that remain to be addressed by our Movement in its new stage, because they are left unsolved even with the formal reality of legislatively protected civil rights:

Income. Over the last 30 years the median family income among Afro-Americans has been 40-45 percent less than the median family income among whites (except for 1969 when it was 39 percent less). If black families received the same fraction of total income as their 12 percent of the total population, their cash receipts would have been $75 billion more than what they actually received in 1980. The picture of stagnation and deprivation represented by these figures unmasks the deceit behind the official propaganda about the rise of the black middle class. The number of middle-income black Americans has indeed risen; but so has the number of permanently unemployed and underemployed black workers whose jobs have been eliminated by technology or the flight of capital investment abroad. Growth without development is increasingly a characteristic of this political economy, and the growth of the middle-income stratum of Afro-Americans is being used to conceal the fact that the community as a whole is being de-developed. In any year during the entire decade of the ’70s, a minimum of two million black workers were unemployed; some estimates put the figure as high as three million.

Housing. A decade ago, our Movement was demanding equal access to housing available for rent or sale without discrimination. Today, the national supply of moderately priced housing is totally inadequate to meet the needs of the average-income family. This shortage is not the result of our lack of access to available housing; rather it is an institutional problem involving the level of monopoly control exercised by the banks and lending agencies over the housing market. We have won an end to racial discrimination in housing, but the housing situation is generally worse today for working and middle-class people than when the Open Housing Act was passed by Congress after Dr. King’s assassination. That act did not address the institutional problem of housing in America; in our new Movement, the role of the banks, and their dominant influence on the ownership of homes, farms and land, must be the focus of our actions.

Health. It is well known that the United States is the only industrially developed country, other than South Africa, that has no government-financed system of national health care, either through national health insurance or the more efficient and less costly form, a nationalized health service. To note but one example of the backwardness of our current health system, the United States, with a two-trillion-dollar Gross National Product, ranks seventeenth in infant mortality; that means sixteen other countries do a better job of saving children’s lives than we do. A health-care system based on private profit is not only inefficient and elitist; it fundamentally perpetuates sickness by surviving off the catastrophic potential of an individual’s disease. A mass movement demanding equal and full health care treatment for all people undercuts the very basis of the current private doctor-patient system that dominates U.S. health policy.

Energy. The private corporate ownership of a natural resource — oil, gas, coal — is another contradiction that stands in the way of solving national problems in the public interest. If there is indeed an energy crisis, then we must set up the rational conditions for the public use of oil, gas and coal in a rational way. Only public ownership — i.e., public control over the manufacture, distribution and sale of energy — allows for the rationally planned conservation and use of these natural resources. The regulatory agency as a substitute for public ownership or nationalization is, by design, inadequate. For example, the Federal Power Commission tried to regulate the price of natural gas in interstate 10 commerce. But since the natural gas is owned by the corporate Seven Sisters, they simply refused to sell it interstate until they could get the price they demanded. So gas shortages are not real, but contrived by those manipulating the market to maximize their corporate profits. If we are serious about dealing with the energy crisis, there is no reason for us to leave the nation’s energy resources in the hands of Exxon, Texaco, Continental Oil, Con Edison and other parasitic monopolies. If the public does not control the sources of energy, we cannot control the solution of the energy crisis. Thus, public ownership of public resources is the prerequisite for a solution to this national problem.

Inflation and Militarism. A major ideological hurdle is being overcome by traditional civil-rights organizations as they increasingly insist, and correctly so, that putting people to work in a full-employment economy is not inflationary. Yet most civil-rights organizations have still not articulated, through their leadership, the position that the military budget is the chief cause of inflation. The question of inflation versus unemployment will continue to be a nagging, tortuous reality because the U.S. economy is sick. It is up to our Movement to popularize the common root of both problems in the use of public resources for military hardware. Inflation is fueled by the wasteful expenditure of government funds for nonproductive, over-priced goods which are continually being destroyed or declared obsolete. Further, for every 1,000 jobs created by investment in military production, the same amount of money would create 1,200 jobs if invested in socially useful sectors of the economy, such as housing, schools, day-care centers and the like. Consequently, spending for the military aggravates unemployment instead of helping solve the problem. It is in the highest national interest, therefore, that the arms race and the military budget be made less attractive to those corporations and politicians whose survival depends upon war and the preparation of war. The world, too, would breathe a sigh of relief if we, the people of the United States, demanded an end to the arms race and the danger of nuclear war. A full-employment economy of socially useful peacetime work for all is the real guarantee of our national security, in contrast to the rampant parasitic militarism which escalates the arms race and pushes the world community toward nuclear annihilation.

A national movement centered on these ideas will require for its achievement the kind of in-depth renovation of the main economic and political institutions that our nation has not seen since the abolition of slave labor more than a century ago. The winning of substantial equality as the national goal of a mass movement will obviously be a protracted, drawn-out battle. It is important in this context to remind ourselves of another lesson we have learned from previous movements of Afro-Americans, women, labor, Hispanics and Native Americans: our journey will inevitably be slowed by two historical tendencies in the official policy of the government and the economic order it serves.

The first tendency is simply delay: to postpone, drag out indefinitely, as long as possible, the recognition of formal equality or equal rights. Then, when this right is formally conceded, to let that stand as the ultimate concession. Under this tendency it took the women’s movement 75 years to get a constitutional amendment (1920) formally acknowledging their right to the vote — a right which didn’t fully materialize until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965, when black women could finally vote in the South.

The second historical tendency involves drawing the line against further gains by reintroducing regressive trends in the life of society. The re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan, the propaganda about “reverse discrimination” and the revival of the old theories of white supremacy dressed in the new academic regalia of “socio-biology” are current examples. The airwaves are also reverberating, as in the past, with messages from the false prophets of the white Christian church in the form of an evangelical crusade — this one called the Moral Majority. Associating love of one’s country with love of the free-enterprise system and support for increasing the parasitic military budget, these evangelist preachers are mobilizing the conservative wing of the Christian church in hopes of drowning out the social gospel of liberation with which the black church in the South has been so prominently identified. In the tradition of all obscurantist movements throughout history, the Moral Majority is designed to pollute the public minds with impressions that create a subservient mass base in support of ultraconservative public policy.

Nevertheless, our protracted struggle for human equality will not take as long as the 300-year struggle for civil rights because the world situation is more favorable today than ever before. The political map is being changed on a global scale by the mass movement of ordinary people who are wiping away the legacy of racism, colonialism and national oppression. Their mass movement is an irreversible force affirming the “somebody-ness” of every member of the human race. The idea of peace, justice and socially useful work for all is no longer an abstraction. Hundreds of millions of people have made this ideal a flesh-and-blood reality as they reorder the economic and political life of their societies.

It is against the backdrop of this ascendant humanism in our age that we, citizens of the United States, must measure the level of civilization we have achieved as a society and the tasks ahead of us as a movement for civil equality. Our Dallas, Texas, November 3, 1979. success in confronting institutional racism in America is inescapably measured by the grim realities of continued U.S. support for such policies as apartheid in South Africa and torture in Central America. As the martyred patriot, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., said in his last speech, “All we are saying to America is, ‘Be true to what you have said on paper.’” Consistent with this commitment to fulfill the ideals of the Declaration of Independence, our Movement’s success will ultimately mean the regeneration of the United States as a civilization and its transition to higher forms of democracy. That vision gives our Movement the authority it must have to overcome the authority of the old order.

The self-interest held in common by Afro-Americans, women, organized labor, Hispanic-Americans and Native American Indians is the foundation for building a new political life in the United States today. Yet in a period in which selfish individualism is encouraged as a substitute for involvement in collective effort, we should guard against the tendency to see “self-interest” in the narrowest meaning of the term. “Be concerned about your brother,” Dr. King said to the people of Memphis in his last speech. “You may not be on strike, but we go up together or we go down together.” That is the spirit of unity and unselfish commitment which has guided every movement that has succeeded in winning substantial victories. And that is the spirit, affirming a global level of mutual respect and common humanity, which will provide the motive force for the authority of our new mass movement.

Tags

J. Hunter O'Dell

Jack O’Dell, formerly a merchant seaman and member of the National Maritime Union, is a longtime activist in the Freedom Movement. He now directs the International Affairs Bureau of PUSH. Since 1963, he has been associate editor of Freedomways magazine, where some of the material in this article originally appeared.