Not By a Dam Site: A Community That Fought Back

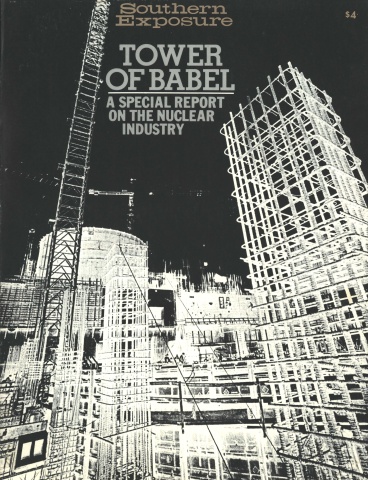

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 4, "Tower of Babel: A Special Report on the Nuclear Industry." Find more from that issue here.

Brumley Gap, Virginia – One of the “givens” of the utility business is that electricity cannot be stored. That is why power companies express so much concern about “peak hour demand,” those times of day when electric use is heaviest, when the demand for power approaches, or even exceeds, the generating capacity of the system.

Pumped storage is one way out of that dilemma. Two reservoirs are constructed, one above the other. During the night, when demand is low, power drawn from throughout the system is used to pump water from the lower to the upper reservoir. During the day, when demand peaks, the process is reversed. Water is released from the upper to the lower reservoir, causing the pumps to reverse themselves and generate electricity.

Pumped storage works, but it is wasteful. On the average, 1.42 kilowatts of electricity are expended for every one kilowatt generated from the pumped-storage facility.

Pumped storage is also expensive. The 3,000-megawatt facility that Appalachian Power Company and its parent, American Electric Power, plan for Brumley Gap would cost more than one billion dollars. Since the total value of all of AEP’s operating plants is now $1.3 billion, that would mean almost doubling the capital investment for a facility that would generate power only six to seven hours a day.

Some pumped-storage projects can have recreational uses. Others cannot. At Brumley Gap, recreation would be impossible – the upper lake would be a three-mile-long mudflat during the day, the lower lake a five-mile-long mudflat at night. A fishing lake on the Hidden Valley Wildlife Management Area would be destroyed by the upper reservoir, while 120 homes and farms would be inundated by the lower.

Pumped-storage projects are generally paired with nuclear plants since, to be efficient at all, they must be connected to a generating system with the lowest possible fuel costs. Once the initial investment is made in nuclear plants, it is relatively inexpensive to run them overtime at night to pump water uphill. Also, nuclear plants are more efficient when run at full capacity at all times of the day; the process of pumping water back to the higher reservoir takes care of the excess output during the off-peak night-time hours. The “nuclear connection” for Brumley Gap would be the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Phipps Bend plant, now under construction, and a nuclear plant which APCO and AEP are proposing near Charlottesville, Virginia.

Opponents say pumped storage is an obsolete way to meet peak hour demand. In the case of Brumley Gap, the Coalition of Appalachian Energy Consumers, the citizen group that is leading the fight against the project, is calling for alternatives that include: direct utility investment in conservation; marginal cost pricing, which gives the consumer more incentive to save electricity; and production alternatives, such as the construction of coal-fired fluidized bed turbine plants, which are both clean and efficient.

In addition, the Coalition has petitioned the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to study AEP’s development plans using the “Willey Model” as a guide. Named after its principal designer, economist W.R.Z. Willey, this computer model analyzes a utility company’s own cost figures to see how the costs and benefits of alternatives compare with those of new construction projects. In 1978, the Willey Model, applied to Pacific Gas & Electric, which was planning eight new plants over an 18-year period, demonstrated that alternative sources could provide enough energy to eliminate all but one 800-megawatt coal unit from the utility’s plans. The California Utility Commission ordered partial implementation of this alternative and praised it for “demonstrating the potential benefits to both ratepayers and shareholders of investments in conservation, as opposed to new plant.”

Currently, seven pumped storage projects are under construction in the South: Fairfield and Broad Creek in South Carolina; Rocky Mountain and Wallace in Georgia; Booth County in Virginia; Davis in West Virginia and Raccoon Mountain in Tennessee. Six more, including Brumley Gap and Powell Mountain in Virginia, have been planned.

In The Beginning

You see stuff like this on TV, but you never think it’ll happen to you. The worst thing about it is the thought that you’ll have to give up your home. I’ve lived in the valley since 1946. Now I go through the house and picture the things that have happened here. The house – it’s nothing compared with the fancy homes you can buy – but it has our memories, the marks on the walls are from our children growing up, all our life is right here. No mansion can take the place of that. — “Cricket” Woods, Brumley Gap Resident

It started quietly enough, with an announcement in the newspapers in August, 1977, that Appalachian Power Company (APCO), the wholly owned subsidiary of American Electric Power (AEP), the nation’s largest privately owned utility, would seek preliminary permits to “study the feasibility” of two pumped-storage hydroelectric plants in the southwestern, Appalachian portion of Virginia.

Only the year before, AEP (which supplies power to western Virginia and parts of West Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana and Michigan) had lost a 14-year battle to build a twin-dam pumped-storage facility on the New River in North Carolina and Virginia. Those dams — the Blue Ridge Project — were scuttled when President Ford signed a bill incorporating 26.5 miles of the New into the nation’s scenic river system.

“Son of Blue Ridge,” as opponents quickly dubbed the new project, would be constructed in one of two locations, or perhaps both, if both seemed favorable: Brumley Gap in Washington County and Powell Mountain in Wise and Scott counties. Each facility would have a generating capacity of 3,000 megawatts, which would make them the largest pumped-storage projects ever built. They would also be very costly, with a price tag of one billion dollars or more each. 765-kilovolt transmission lines would extend from the plants south to the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Phipps Bend Nuclear Plant, now under construction, and northeast to a nuclear plant Appalachian would later propose for central Virginia, in Nelson County near Charlottesville.

In applying for the preliminary permit, APCO/AEP have requested permission from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to reserve the two sites while they study them for about three years. If the studies prove favorable, the utility can petition for a license to build. Construction would begin sometime in the mid-1980s.

The Powell Mountain project would destroy 25 homes and part of the Jefferson National Forest, including one section, Devil’s Fork, being considered for wilderness designation. It would also render useless the Big Cherry Reservoir, which supplies drinking water to the town of Big Stone Gap.

The Brumley Gap Project would flood out 120 families and inundate parts of a state game preserve, making the preserve’s Hidden Valley Lake unsuitable for any kind of recreational activity. It would also destroy lands that may have tremendous archaeological significance. Over the years, residents have found thousands of Indian relics. Hunter Holmes, who used to operate the Country Store in the valley, recently found, and had verified, a flint arrow point that dates to the Paleo period — 9,000 years ago. A local archaeologist says the valley is “just one Indian camp after another.”

There wasn’t too much excitement about the projects at the time the announcement was made. Few people outside the immediate area had ever heard of Brumley Gap or Powell Mountain; even in nearby towns there wasn’t much concern. After all, the nation needed energy, didn’t it? And these projects weren’t like the old Blue Ridge dams, where a priceless natural legacy — the New River, reputed to be the second oldest in the world — would be destroyed. Only a few farmers and sportsmen would be affected, and they, of course, would be fairly compensated for land they were forced to give up.

That was two years ago. Things are far from quiet now.

With the help of the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund and the quickly formed but carefully organized Coalition of Appalachian Energy Consumers, those few farmers and sportsmen have confronted APCO and AEP with an opposition that is as well-organized, as effective and as determined as the resistance to damming the New River.

As a result, APCO/AEP have cancelled plans to study the Powell Mountain site. Brumley Gap residents have kept the utility company from disturbing their land, they’ve held their own in the legal and political confrontations that have taken place in the past two years, and they are now working to convince the FERC that the project is not needed, that better means are available to meet future energy needs.

Brumley Gap is an unlikely place for a struggle of such intensity. It is a narrow but fertile valley that lies between the Clinch and Little Mountains in northern Washington County, on the edge of Virginia’s coalfields and immediately adjacent to state-owned gamelands in the Hidden Valley Wildlife Management Area. Brumley Creek, which flows down the slopes of the Clinch from Hidden Valley, harbors trout, both native and stocked, in its clear, unpolluted waters.

The valley was settled sometime soon after the Civil War by five families — the Lees, the Lillys, the Mitchells, the Warrens, the Scotts. Those names are still prominent in Brumley Gap today, as are relatively “new” names like Duncan, Alexander, Wise, Woods, Scyphers. Even the newcomers can, in many cases, trace family ties back three and four generations.

It would not be not accurate to say that Brumley Gap is one of those places where “time has stood still,” or anything like that. Certainly, changes have occurred. For those residents who still farm, the tractor has replaced the mule; the automobile, or the ubiquitous pick-up truck, has replaced the horse and buggy. Most working-age men and women commute to jobs in Abingdon or Bristol or Lebanon or other nearby towns. They farm part-time, or simply garden.

However, in many ways the area has changed less than most other parts of the country. People still raise corn and beef and milk cattle, and still grow burley tobacco as a cash crop. Community life still centers around Mike Wise’s S&W Grocery and the Davy Crockett Coon Hunters’ Club, a metal building that once served as a chicken house but is now the headquarters for the Brumley Gap Concerned Citizens’ Association as well as the coon hunters.

At the heart of the community are three churches — Methodist, Baptist, Church of Christ. Remnants of the rural mountain way of life still exist, not as nostalgic curiosities, but as elements in a living culture. Women still gather to quilt, men still hunt and fish and work the land. People still believe in the verities of religion, hard work, neighborliness. One of the most cherished values of Brumley Gap people is independence. Lee McDaniel, secretary of the Concerned Citizens Association, explains: “They cleared the mountains. Everything they ate they grew. They don’t ask for nothing from society — they give to society.” Then, thinking about some of the people she’s encountered on the other side, she adds: “I’d like to see some of those people who make a living by lying and cheating and being politicians go over there and try to make a living by the sweat of their brow.”

Despite the emphasis on self-reliance, there is a recognition that cooperation is necessary — not the kind of cooperation that civic groups talk about when they conduct a fundraising drive, but something deeper, something known in our society by a very few, realized most profoundly, perhaps, by dirt farmers and their descendants, people who have come face to face with an environment that is rarely benign and often hostile, who have developed over the years a visceral understanding that to survive, men and women must work together.

Lee McDaniel recalls the time when men from surrounding farms would gather at her father’s place to help with the work while the women went into the kitchen and cooked for the crew. Later, it would be her father’s turn to donate his labor to his neighbors.

Sitting in his store, Mike Wise brings that up to date: “If I need a piece of equipment,” he says, “I know I can get it from a neighbor. If I need a helping hand to move something, here I know I can get it. If we had to move into a city, I’m afraid we’ll lose those things.”

There is another trait common to the valley. Sam Dickenson, the high school social studies teacher who is president of the Concerned Citizens, explains that, until recently, land wasn’t sold to outsiders. Instead, it was “passed back and forth in the valley.” That’s not as true today as it was just a few years ago, but the sentiment is still there: a deep love of the land, not just the land as an abstract, as an ideal — people of the valley are not environmentalists in the usual sense of that word — but of particular pieces of land, tracts that have become inextricably associated with family and friends, with a way of life and a belief in the harmony of God’s creation.

Pumped Storage Test Case

None of those qualities appeared to be of much use in late 1977 and early 1978, when the full impact of APCO’s plans for the valley was beginning to be felt. There was a desire to fight but little understanding of what needed to be done. Lee McDaniel puts it succinctly: “We’re hillbillies. Everything works against us being able to deal with something like that.”

Help came unexpectedly from neighboring Scott County, in the person of Richard Cartwright Austin, a United Presbyterian minister who lives near the proposed Powell Mountain site. Austin, who calls himself an “environmental theologian,” has extensive experience in dealing with social and environmental issues. He is the author of a book, published by the Sierra Club, on the environmental effects of strip mining, and has been active in a Scott County organization, Save Our National Forest, which successfully pressured the U.S. Forest Service to prohibit strip mining in the area. Austin and his group also petitioned the Forest Service to include part of Powell Mountain — Devil’s Fork — in the nation’s wilderness system.

The members of Save Our National Forest were alarmed that an area as unique as Devil’s Fork would be destroyed. More than that, they were concerned about the 25 local families who, like the people of Brumley Gap, would lose their homes and way of life.

Early in 1978, Austin met with APCO representatives. Later, he drove to Blacksburg to talk to professors at Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University – VPI’s Center for Environmental Studies had a contract with APCO to do environmental studies of the two dam sites.

What he discovered at VPI made him angry. The college professors had agreed, for $500,000, to do a highly restricted “study” that would ignore several important environmental concerns. The university consented to keep the results of the study secret for a year after it was completed. Moreover, the contract with APCO gave the utility company the power to “modify” VPI’s findings as it desired. In an article for The Plow, a regional newspaper in Abingdon, Austin wrote that VPI had betrayed its responsibilities as a land grant university: “For a half-million they have sold their academic souls to become spokesmen for a private interest on this critical regional issue.” He characterized the university officials as “nice, well-intentioned people. Unlike professional whores, they don’t know when they’ve been bought and sold.”

By March, Austin and his group had decided they would oppose the Powell Mountain and Brumley Gap projects. “We needed some kind of wide-ranging coalition that would include the Brumley Gap people — it would be foolish to fight the dams off here just to send them down there. And we needed sophisticated legal help.”

The legal help came from the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, which was just setting up a Washington office when Austin visited there in early spring. James H. Cohen, the Fund’s chief Washington attorney, thought the time was ripe to fight the concept of pumped storage in general. There was ample evidence that, besides rendering many square miles of land totally useless, pumped-storage projects were too expensive, wasteful and outdated as a method of meeting peak demands for electricity. Brumley Gap and Powell Mountain would be test cases for the 30 or so similar projects either underway or planned throughout the nation.

From May to July, Austin worked with Sierra Club lawyers to prepare the first document the Club and his recently organized Coalition of Appalachian Energy Consumers would submit to the FERC: a request that they be recognized as intervenors in the permit process.

In May, Austin went to Brumley Gap and talked with Mike Wise at his store. It was a Thursday, and Mike told him to come to the coon hunters’ club the next Monday night. He would get “a few people” together. When Austin got there on Monday he found almost 100 gathered, representatives of nearly every family in the valley. Thinking back on that now, he says, “I’ve never had a clearer experience of working as a catalyst. Everybody was ready to do something, but no one knew where to start.”

After he discussed strategy with them, the Brumley Gap people didn’t waste any time. On that same night, they elected officers and a steering committee, authorized participation in the organizational meeting of the Coalition, and assessed every family in the valley $100 as the beginning of their own legal defense fund — to hire lawyers to keep APCO from coming on their land to conduct site tests.

The people learned fast. In the course of two years, members of the Brumley Gap Concerned Citizens held festivals, staged beauty contests and turkey shoots and fishing contests, sold quilts and chicken dinners and T-shirts emblazoned with the Coalition motto, “Not By A Dam Site.” They even planted a crop of burley tobacco for the cause.

Lee McDaniel recalls, “I started in Abingdon one night and by the time I got to Brumley Gap I had $3,000, either in hand or promised. Everybody in the valley paid $100 except for about five families. Some of those who couldn’t pay that — old people or young couples just starting out — well, they gave $25 or $10 or $15.” The Concerned Citizens also learned to handle the press. The first time Lee talked to a reporter she got a shock. “I knew he was going to print what I said, but I didn’t know he was going to say I said it. Now I know — don’t say anything you don’t want to see in print.”

Local papers, which usually contented themselves with printing power company press releases, began to do in-depth articles about the opposition and even, in some cases, to question the need for the dams. Time featured Brumley Gap, as did the English National Guardian. An independent filmmaker came to the valley to document the struggle.

People outside the valley were impressed by how well organized the Brumley Gap Citizens became, but those inside took it for granted. “I wasn’t surprised,” says Sam Dickenson, “I knew the people.”

The Coalition held its first meeting on May 13, 1978, in Abingdon. Seventeen groups, representative of citizen interests throughout APCO’s service area, joined: from Virginia – a the Brumley Gap Concerned Citizens, the Consumer Congress of Virginia, the Council of the Southern Mountains, the Old Dominion Sierra Club, Save Our National Forest, the Scott County Sportsmen’s Association, United Citizens Against Fuel Adjustment; from West Virginia – Citizens for Environmental Protection, Save Our Mountains, Save New River, Stop the Powerline, West Virginia Citizen Action Group; from Kentucky — Knott County Citizens for Social and Economic Justice, from Ohio — Ohioans for Utility Reform; from Tennessee — Kingsport Power Users. The Environmental Policy Center in Washington also joined.

Eventually, the total membership rose to 20 groups. Grant support came from the United Presbyterian Church and the Youth Project. The Catholic Daughters of the Holy Spirit sent a sister, Kathy Fazzina, to serve as a coordinator and field worker.

Others joined the fight. Because of concern over the “nuclear connection” — the fear that the two projects might mean a turn away from coal — the city of Charleston, West Virginia, and three United Mine Workers locals filed to intervene. The town of Big Stone Gap, Virginia, also filed because of the chance that its water supply could be destroyed.

Back in Brumley Gap, the primary concern was keeping APCO off the land. By submitting a preliminary application to the FERC and announcing its intention to study Brumley Gap as a dam site, APCO had started a process that, according to most interpretations of Virginia law, gave it the power to come on the land and make site tests.

On June 11, residents received a letter from the power company, asking permission “to make such surveys and examinations as are necessary to determine if the site is suitable for the possible location of a pumped-storage hydro-electric generating facility.” The letter promised “no harmful effect on the property,” but warned that unless permission was granted, APCO would exercise its right to enter the land without the owners’ permission.

In response, the Brumley Gap citizens got together and sang “We Shall Not Be Moved” while 76-year-old Roby Taylor burned the letters.

APCO wrote again, this time sending the letters by registered mail. All but a few residents refused to accept them.

Tension ran high in the valley. Some of the older residents began to show signs of physical distress, caused, relatives said, by worry over the prospect of having their land disturbed. People talked about greeting APCO with buckshot, and discussed the prospects of going to jail to protect their land. Austin told them that if everyone stuck together, “They just might have to build a bigger jail over in Abingdon.”

Austin was concerned about two things — first, that violence might occur, and second, that the people would not be prepared to resist APCO effectively. He called for help from the Movement for a New Society, a non-violence training group which had emerged from the American Friends Service Committee. In August, during the week before APCO would have the legal right to come on the land, Pete Hill and two other trainers came to the valley and began conducting workshops in people’s homes. The subject: non-violent civil disobedience tactics.

Some of the Brumley Gap people were nonplussed by the workshops, others thought they were useful, a few thought they were “silly” - but they attended them with the same enthusiasm they had directed to every other task. Whatever the people thought about them, APCO took the classes seriously. Two days before the power company was scheduled to begin site testing, sheriff’s deputies served warrants on 62 residents.

The warrants indicated that APCO had stepped back from the possibility of confrontation. Instead of forcing the issue directly, it had decided to go to court, to seek an injunction which would prevent the citizens from barring entry to the land.

The papers were served on Saturday morning, August 11, the first day of the First Annual Brumley Gap Festival. At a rally on the next afternoon, Austin explained the significance of what had happened: “APCO would rather pretend they’re up against individuals and try to ‘pick us off one by one. They can’t do that now. By going to court, they’ve recognized that we’re together. Now we’ll stand together and fight them.”

Meanwhile, information about the “tests” began to surface. They weren’t quite as harmless as the power company had claimed. Test pits and trenches would be dug, roads would be cut across private property, a tunnel would be drilled back into the mountains. The people agreed — if APCO was permitted to do this kind of work, they might as well move out. The valley would be ruined. Lawyers were hired — a Republican, Strother Smith; a Democrat, Emmit Yeary. (Later, Yeary’s partner, Mary Lynn Tate, would also work on the case.) The Citizens weren’t taking any chances on slighting anyone politically.

As the November, 1978, hearing approached, neither the lawyers nor Austin were confident. The law seemed clear — APCO had the right to come on the land. Then, says Austin, “a beautiful thing happened.” The first witness to testify at the hearing was Kenneth L. Dickson, Director of VPI’s Center for Environmental Studies. APCO had brought Dickson to the hearing so he could testify about how the environmental studies would serve to protect landowners. However, under cross-examination by the Brumley Gap lawyers, he admitted that the environmental studies could not be conducted properly unless they were completed before the site tests were made.

“There was an immediate recess and a huddle around the judge’s table,” Austin recalls. “Then they came up with a compromise — we agreed not to stop APCO and VPI from surveying and conducting environmental studies, but they agreed not to do anything that would disturb the land. We gave up something we didn’t really care about; we kept the one thing that wasn’t negotiable — they could not tear up the valley.”

Another hearing was scheduled for February 26, 1979.

“They were going to sell us out.”

In the meantime, another, more difficult battle was going on — that was to convince local politicians to get off the APCO bandwagon and keep an open mind about the projects. Soon after the project was announced, APCO Division Manager Jerry Whitehurst had toured local governments and, according to Austin, “dangled multi-million dollar tax benefits in front of their eyes.” As a result, several local governments, including the Washington County Board of Supervisors, had quickly endorsed the studies without even notifying the Brumley Gap citizens that the matter would be on the agenda.

The endorsement came in April, 1978. Two months later, the supervisors rescinded that action, since no public hearing had been held on the issue, and said they would remain “neutral” until more information became available. The Brumley Gap citizens weren’t reassured by the move — they felt that the board, which was dominated by real estate and land development interests, was simply waiting for the most propitious moment to endorse APCO’s study once again.

Lee McDaniel tried to give the supervisors copies of the brief the Coalition had sent to the FERC. She told them it would prove that the project wasn’t really needed. Only one of the supervisors who had voted to endorse APCO’s study accepted her offer. The others said they weren’t interested.

If the members of the board of supervisors weren’t convinced by the arguments advanced by the Brumley Gap citizens, they were concerned about one thing — the threat of violence. On July 26, to reduce tensions, the board appointed a Citizens Advisory Committee, made up of county residents, including some of the Brumley Gap people, to “discuss all details” of the project and “make a full report” to the board in the fall. The supervisors also requested that APCO cease work on the project until the committee had made its report. (The power company ignored this request.)

Most people felt the creation of the committee was merely a way of pacifying the Brumley Gap citizens without really doing anything. The power company didn’t take any chances though. Shortly after the committee formed, APCO’s Jerry Whitehurst made an unscheduled appearance before the board of supervisors and announced he had some good news — if the Brumley Gap project was built as planned, the county would reap a tax benefit in excess of $4 million. Whitehurst claimed this would double the county’s tax base and make it possible to cut property taxes for local residents. The project would also, said Whitehurst, mean lower electric rates in the future.

The timing of the announcement made members of the committee furious. They felt it was a deliberate attempt to undermine their work. Hunter Holmes, one of the Brumley Gap representatives on the committee, says, “They [the county supervisors] were going to sell us out. They intended to ignore us for the ‘betterment’ of Washington County.”

Nevertheless, the committee dug in and began work. They got into more than just pumped storage. Their 70-page report to the board discussed alternatives to pumped storage, conservation, APCO’s past and future rate hike demands, the “nuclear connection,” the potentially harmful effects of 765 KV lines, and ways that citizens and local governments could take part in the licensing process.

The committee made one recommendation — that the board of supervisors submit a late intervention to FERC “requesting an evidentiary public hearing on APCO’s preliminary permit application. . . .” Only in this way, they felt, could the interests of county residents be protected. The public hearing would also let the Coalition and the Brumley Gap citizens submit updated information to FERC.

Winning Friends

From mid-October, when the committee delivered its report, through mid-December, the board of supervisors met four times to discuss the issue. A lot was said, but no action was taken. The Brumley Gap citizens felt the board was stalling, trying to find a logical reason for not honoring the request for a public hearing.

In the meantime, APCO stepped up its efforts. Whitehurst had come back before the board, telling the supervisors that tax revenues from the dam project “would eliminate worries which farmers have about being taxed off the land, would just about eliminate worries about financing the Washington County school operation, would make the county even more attractive to industry.”

Other company attempts to gain political support for the project came to light. In Abingdon, a regional newspaper, The Plow, published an article entitled, “How To Win Friends In The Utility Business,” which detailed the following:

• In late 1977 or early 1978, APCO had gone outside its regular purchasing procedures to buy two Jeeps from a dealer in Big Stone Gap. The purchases were not made on the basis of a low bid, as was usually the case, and the salesman was Robert Whitt, at that time one of the three Big Stone Gap Town Councilmen who had voted to endorse the Powell Mountain Study. When enraged citizens cornered him after the meeting, he is reported to have explained his vote by saying, “They bought a couple of Jeeps from me.” (Whitt denies making the statement).

• Another Big Stone Gap Town Councilman experienced job pressure after voting against endorsing the Powell Mountain study.

• Lee McDaniel’s employer received a letter of protest from Jerry Whitehurst after she listed her office telephone number in an ad concerning an APCO rate hearing. She felt the letter was intended to place her job in jeopardy.

• In Washington County, APCO remained silent as the county planning commission and board of supervisors acted to rezone a property next to one of its industrial sites for residential use. The property was owned by Warren McCray, a developer who is also a member of the board of supervisors and the local planning commission. McCray had worked with APCO in the past to develop a “total electric” subdivision in Abingdon. He was a personal friend of Whitehurst’s. He had also voted to endorse the Brumley Gap study. A local planning official commented, “That [the APCO property] is a speculative site. There’s no way it wouldn’t have an ill effect on them to have the land rezoned. . . .” (The manager of a Westinghouse plant, which is also next to the rezoned land, protested the change before both the planning commission and the board of supervisors.)

Whitehurst tried another approach — to discredit the committee’s report and to identify those who opposed the study as outsiders. At one board meeting, he termed the committee report “propaganda.” In private conversation he described one member of the committee as a “long-haired, bearded radical.”

At a board of supervisors meeting on October 24, this kind of rhetoric backfired. Whitehurst told the board members, “Appalachian has been a good citizen of this community for over 50 years. Some of the people who are speaking against us are here today and possibly won’t be here tomorrow.”

Brumley Gap residents burst into laughter at that. One remarked to another in a voice that could be heard across the meeting room, “He’s makin’ dam sure of that.”

Coming to Grips

Finally, on December 20, the Washington County Board came to grips with the question of a public hearing on the Brumley Gap project. In a meeting which lasted more than two hours, citizen after citizen came before the board and made quiet but impassioned pleas for a chance to take their case to a public hearing before the FERC. One board member commented that APCO had never said it wanted to take the valley — it just wanted to study it. To this, Brumley Gap resident Jim Woods responded that he knew another politician who was an undertaker: “I bet he never ‘studied’ a grave unless he had a body to put in it.”

Mary Lynn Tate, one of the Brumley Gap lawyers, stood before the board to talk about things which had come to light since the committee delivered its report. Holding a copy of a sworn deposition taken from Jerry Whitehurst in her hand as she spoke, Tate told the board members the APCO division manager had admitted under oath that he had no documentation on hand, nor did he know of any documentation, for the claim he had made that electric rates would drop and four million dollars in tax benefits would result if the Brumley Gap project were built.

There were a few more comments after Tate’s remarks, then Jim Litton, the supervisor whose district includes Brumley Gap, moved that the board honor the advisory committee’s request and petition the FERC for an evidentiary public hearing. The room was silent as the supervisors raised their hands to vote, then the Brumley Gap citizens began to cheer — the vote was four to three in favor of the hearing. Two supervisors had changed their minds.

Other victories followed. On February 23, 1979, APCO unexpectedly announced that the utility was giving up its study of the Powell Mountain site. On the same day, APCO attorneys asked the state court to postpone indefinitely their request for an injunction against the Brumley Gap citizens. They had decided, they said, to delay site testing until all of the environmental studies were finished. (Austin says the real reason for the delay was that APCO had seen the strong pre-trial briefs filed by the Brumley Gap lawyers.)

A Cautious Optimism

In spite of the victories, the people in Brumley Gap express only a cautious optimism that they will be able to save their valley. They recall the hard work that enabled them to raise the remarkable sum of $18,000 in only two years. Then they consider the millions of dollars that APCO and AEP would spend simply to run tests on their land, the billion or more dollars the utility would spend to build the project.

People in the valley have seen copies of the detailed work plan APCO sent to the FERC in defense of its request for the preliminary permit. It calls for 25 core drill sites, 55 test pit sites, 20 soil bore holes, an unspecified number of bulldozer trenches, plus approximately 40 sites not yet located by APCO.

The citizens have inspected the sites. They estimate the work would require over 13 miles of new roads, remove 246 acres of land from productive uses, pollute streams and wells and involve dangers to children and livestock. One core drill site, they note, would be only 10 yards from a home.

In September, a four-man inspection team from the FERC staff came to Brumley Gap to get a first-hand look at the valley and to examine some of the test sites. The visit itself was an encouraging sign — it’s the first time the FERC has sent a team to inspect an area during the preliminary permit process, an indication the agency takes the Coalition and the citizens seriously.

On the other hand, Brumley Gap residents received no assurances from the FERC team members that the regulatory agency will deny APCO the preliminary permit, or that the FERC will require the utility company to carry out studies of alternatives before doing the site tests. It seems certain the preliminary permit will be issued.

During their visit, the FERC staff members urged the Citizens to “negotiate” with APCO to minimize land disturbances while the site tests are going on. The citizens say they aren’t going to do this. For one thing, their case in the state courts is stronger now. The local lawyers have done their homework well — case law in Virginia and other states suggests that APCO may have to demonstrate the need for the dams before it can come on the land without the landowners’ permission. Or, the company may have to go to court and try to condemn all the land in the valley — purchase it outright at a price established by the courts. APCO doesn’t want to do that at this stage of the game.

There is a feeling in the valley that it’s time to force APCO’s hand. Lee McDaniel says, “If they want to come on our land and mess it up, let them go to court and prove the need. That’s all we ask — let them prove they really need our valley.”

Determination still runs strong. FERC is expected to rule on the preliminary permit application this fall. The Citizens have chartered a bus to go to Washington and attend that meeting. They say they want to “look the FERC in the eye.”

Sam Dickenson contemplates the damage that would be done to the valley if, after all this, APCO is able to do the tests, then adds, “Even then, we might try to stop the dozers.”

Thirty miles away at his farm in Dungannon, Dick Austin talks about some of the legal steps open to the Coalition. Phase I of an archeological study has just been completed and a second phase recommended. That will buy some time. The Coalition and the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund have the option of going to court to try to force APCO to do a complete Environmental Impact Statement on the test sites. That would buy more time. “There’s still a hard fight ahead,” he says, “but the threat to Brumley Gap today is a lot less than it was two years ago.”

Back in Brumley Gap, Hunter Holmes sits on his front porch and thinks back on the experiences of the past two years. He’s not bitter, he says. “I still think our judicial system is basically sound. The common man has a chance against big corporations. That’s what America should be all about — giving the little man a chance.” He smiles wryly and adds, “Too often, though, people get bought off. Then you don’t have justice, you have ‘corporate’ justice.”

A few miles down the valley, Cricket Woods sits in her living room, surrounded by photographs of her five children and other mementos of more than thirty years in the valley. She recalls a trip she took to Charleston, West Virginia, to attend an American Electric Power Company stockholders’ meeting. There she talked with John Vaughn of APCO. “I asked him why they didn’t come and talk to us if they wanted our valley. He said, ‘Maybe we should have.’ He told me that APCO learns by their mistakes. So I asked him, ‘Suppose you woke up in the morning and read in the papers that they were going to take [your] home? How would you feel then?’ He didn’t answer that.

“We’ve had to do a lot of work to keep this valley, but we’ve enjoyed it, and enjoyed each other. Even if we lose, APCO has brought us together,” she reflects.

“You get up each morning and look at the valley. It’s always seemed pretty, but now you take it in more, appreciate it more. I always look up in the hills at Pinnacle Rock when I’m working outside, and I thank God for my life here. If I have to leave, then I’ll just thank him for letting me live in the valley all these years.”

Tags

Bill Blanton

Bill Blanton is a former editor of The Plow in Abingdon, Virginia. He is now a free-lance writer and photographer working out of Scott County, Virginia. (1979)