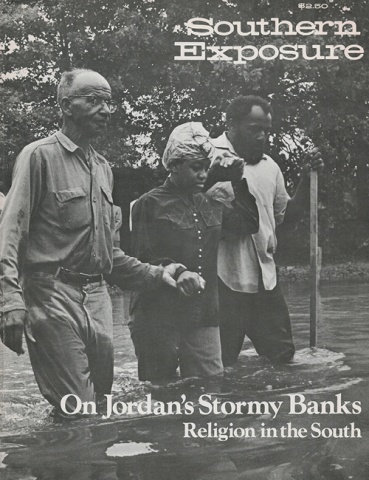

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

In the winter of 1959-60, the nation was mesmerized by a group of young, black college students in Nashville, Tennessee, who appeared at a segregated lunch counter one Saturday afternoon and asked to be served. All that spring, they filled the jails and the nation with their freedom songs, sparking similar actions and demonstrations across the South. Although an earlier sit-in had been held in Greensboro, North Carolina, it was the small coterie of Nashville students who gave impetus to the concept of nonviolent direct action, and continued to provide critical leadership as the Movement spread.

By the spring of 1963, many of the students had moved on to help organize other Southern cities. Still the Nashville movement persisted. The Nashville Christian Leadership Council (NCLC) held mass meetings regularly, and the local chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) continued to demonstrate for open public accomodations.

One of the demonstrations stands out clearly in my memory. It was a chilly spring afternoon. The demonstrators were mostly high school students; the target was one of downtown’s “fancier” restaurants, the kind that most of the students would not be able to afford once it was opened. They left the First Baptist Church holding hands and singing, showing not the least sign of fear. They returned almost immediately, some hurt and bleeding, running to avoid the violence that had awaited them. They were cared for and sent home. They were also asked to return the following day for another demonstration at the same location.

A few of us were left in the front of the church, talking quietly, trying to make some sense of a situation where none existed. There was a commotion in the back and we looked up to see four or five young white guys. No doubt, they had been partly responsible for some of the blood that had been shed earlier; their hostility had apparently only been whetted by the confrontation. They stood now in the doorway, threatening, yet showing some signs of discomfort and wavering bravado, a little unsure that it was cricket to make trouble in a church.

I had been more than slightly shaken by the events of the afternoon, vulnerable to all the feelings of ambivalence and helplessness that were all too familiar to white Southern students of my generation. And now, I sat stunned by the fact that they had actually come into the church, obliterating by their very presence my make-believe lines of us and them. They could easily have been the good old boys from my high school, the ones who had joined the army or gone to work in the local paper mill because that was what everyone expected them to do.

Wanting desperately to put some distance between myself and them, I muttered something about “how dare those thugs come into church. ” I had expected at least a murmur of approval. What I got was a stern, but gentle reprimand from John Lewis. He looked me straight in the eye and said, “Don’t call them thugs. You have no right to do that. They are human beings just like you and me.’’ For the first time I understood clearly what it meant to accept nonviolence as a way of life.

Later that spring, John became national chairman of SNCC. He was in and out of jail constantly over the next few years, and was beaten badly at the Edmund Pettus bridge in the first attempted Selma to Montgomery march. Yet, I never saw his commitment to nonviolence waver.

For the early civil-rights movement, indigenously Southern, and deeply rooted in the black church, the philosophy of nonviolence and the Christian ethic were totally complementary. In the following interview, John talks about that early Movement, its deep commitment to the philosophy of nonviolence and its integral ties with the Christian faith.

John Lewis is now the Director of the Voter Education Project in Atlanta, an organization that has continued the work of registering black voters in the South. For John it is a continuation of the work he started in the early '60s, a Movement that has progressed from lunch counter sit-ins to the attainment of black political power.

— Sue Thrasher

I’m the third child in a family of ten. I grew up on a farm near Troy, Alabama. When I was four years old, we moved from where we worked as tenant farmers to a new farm about a half a mile away. My father had saved enough money in 1944 to buy 102 acres of land for a little more than $300; they still live there today.

When we got settled at this new house on the swamp, it became my responsibility to raise the chickens. At the same time, I had a growing interest in religion and going to church so I started playing church with the chickens. This is the truth — I tried to baptize the chickens, and in the process, one of them drowned. I felt very bad about it, but it did not discourage me. I did not lose my great interest in raising chickens, in a sense, my love for them.

I really don’t know where my interest in religion came from. It could be my family; we all went to a Baptist church — my mother, my father, most of my first cousins. My grandfather was a deacon. See, in rural Alabama, we only had church once a month. So every third Sunday we would go to a regular church service; that’s when the preacher came. When he wasn’t there, we went to a Methodist church that was right down the hill below our house.

During that period, when I had a belief in Santa Claus, one of my uncles had Santa Claus bring me a Bible for Christmas. It had an impact. And somewhere along the way I grew up with the idea of wanting to be a minister. It was well known in the family. One of my aunties would call me preacher.

I have six brothers and a host of first cousins about my same age; we all sort of grew up together. It was like a big fellowship — really an extended family. When we went to Sunday school and church it was the whole family, not just the immediate family.

Religion, the whole idea, played a tremendous role in my family. We all had to learn a verse of the Bible at an early age. We had to do that. Before meals we had to say grace and then we all had to recite a verse; it’s still done even today. On special occasions like Thanksgiving or New Year’s or Christmas, my mother or my father or one of us had to lead a prayer.

My interest in the chickens and my interest in the church sort of came together. In addition to helping my family raise the chickens because we needed eggs — it was a necessity, being poor in rural Alabama — the chickens became part of an experiment. I would preach to the chickens each night when they would go into their coop, or what we called the hen house. It was my way of communicating to them. When a chicken would die, we would have a funeral. My younger sisters and brothers and first cousins would be the mourners. We had a chicken cemetery where we buried them and had flowers and everything. I recall a large pecan tree that’s still there today; we had a swing and benches under it, and we would gather there to have the services. People would line up like they were in church. The service would dismiss, and we would march off to the cemetery below the house.

The grade school that I attended for the first three years was in the Methodist Church, just below our house. It was a public school, but they used the church building. Next door, there was another one-room school where we went to the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades. After the sixth grade, we took a bus to a little town called Banks, Alabama; I took junior high school in Banks. The high school was located in Brundidge, going on down toward Ozark. We passed the white school on our way. We had this old, broken-down bus. Many of the black families in this area owned their own land, and the county actually skipped parts of the road — the area where blacks owned land was not paved. So, some mornings when there was a lot of rain, the bus would run in a ditch and we would get to school late. Or coming from school, the bus would get stuck in the red mud coming up a hill, and we wouldn’t get home til late at night. That happened on several occasions.

We were very, very poor, like most of the black people in that area. And I wanted to go to school. I wanted to get an education. On the other hand, we had to stay out of school to work in the field, to pick cotton or pull corn, or what we called “shake the peanuts.” From time to time, I would get up early enough in the morning to hide. On two or three occasions I actually went under the house and waited until I heard the bus coming; then I ran out and got on the bus, so I could make it to school rather than work. My parents used to say I was lazy, because I didn’t want to stay out and go to the field. But I saw the need and I wanted to go to school. That was particularly true during my junior high and high school years.

We didn’t hear much discussion about civil rights. It was strictly two separate worlds, one black and one white. When we’d go into the town of Troy, we saw signs, “Colored only,” “White only.” The water fountain in the five and ten store. At the courthouse. Couldn’t use the county library. I don’t recall hearing anybody speak out against it. The closest thing was to hear the minister say something like, “We are all brothers and sisters in Jesus Christ.” Or through the Sunday school lesson, particularly those lessons based on the New Testament, it came through: “In Jesus we are one.” That had an effect. That influenced me, no question about it.

In 1955, at the beginning of the Montgomery bus boycott, when I started taking note of what was happening there, we didn’t have a subscription to the Montgomery paper. But my grandfather had one, and after he read his paper, we got it two or three days later, so we could keep up with what was going on.

We didn’t have electricity during those early years. We didn’t get it until much later. We had a large radio, one with these huge batteries, the kind that have to be knocked open with a hammer when they decay. There was a local station in Montgomery, a soul station, black-oriented, but I don’t think it was black owned. Every Sunday morning a local minister in Montgomery would preach, and one Sunday I heard Martin Luther King. Now this was before the bus boycott. The name of the sermon was something like “Paul’s Letter to American Christians.” He made it very relevant to the particular issues and concerns of the day. That had an impact. I also heard other ministers on the station. Our own minister was very aware and talked about different things.

The bus boycott had a tremendous impact on my life. It just sort of lifted me, gave me a sense of hope. I had a resentment of the dual system, of segregation. Because I saw it. You could clearly see the clean new buses that the white children had that were going to Banks Junior High and the buses that were taking white children to Pike County High School. You see, in the state of Alabama, most of the black high schools were called training schools. So in Brundidge, my high school was called Pike County Training School, and the white school was called Pike County High School. That was true of most of the counties in Alabama at that time. In Montgomery, they were saying something about that dual system.

I remember in ’54, the Supreme Court Decision, I felt maybe in a year or so we would have desegregated schools. But nothing happened. Then Montgomery came in 1955. It was like a light. I saw a guy like Martin Luther King, a young, well-educated, Baptist minister, who was really using religion. The boycott lasted more than 300 days; it had a tremendous effect.

During that period, I think it was February of 1956, I preached my first sermon. I must have been about a week short of being sixteen. I told my minister I felt I had been “called” — in the Baptist church, you hear the “call” - and that I wanted to preach a sermon. And I preached. I don’t remember the verse, but it was from First Samuel. My subject was a praying mother, the story about Hannah, who wanted a child. I’ve never forgotten it — the response. I got up, took the text, gave my subject, and delivered a sermon. The response of the congregation was just unbelievable! I was really overcome by it all.

From that time on, I kept preaching at different churches, Methodist and Baptist churches in the rural areas of Pike County. Churches in Troy would also invite me to come to preach. I continued to do that until I graduated from high school in May, 1957. In the meantime I had been ordained by my local church.

My greatest desire at that time was to go to school — to get an education, to study religion and philosophy. Somehow, I knew that this was the direction I must travel in order to become a prepared minister and to be a good religious leader.

I had a fantastic urge to go to Morehouse College. I’d heard of Morehouse, and I knew that Dr. King had gone there. I had my homeroom teacher get a catalogue and an application from Morehouse. But there was no way. I did not know anybody. I didn’t have any money. It was just impossible. So this was a dream that was never fulfilled.

My mother had been doing some work for a white lady as a domestic, and one day she brought home a paper. It was something like the Baptist Home Mission, a Southern Baptist publication. In this paper, I saw a little notice for American Baptist Theological Seminary (ABT). It was the first time I had heard anything about the school. I’m not sure if it said for blacks or for Negroes or what, but it said, “no tuition, room and board.” And I wrote away. I got an application, filled it out, had my transcript sent up, and got accepted.

So in September, 1957, I went away to Nashville. That was my first time to leave Alabama for any period of time. I was seventeen years old. I’ll never forget that trip, getting on that Greyhound bus; it was my first time to travel alone. Nashville was altogether different from rural Pike County, Alabama. It was just another world. I didn’t know what to believe. I knew I’d left something and was going to something new.

They had a work program at ABT, and I got a job in the kitchen washing pots and pans. I was paid something like $45 or $46, and $42.50 was taken out for room and board. The school is jointly owned by the Southern Baptist Convention and the National Baptist Convention. It’s primarily the financial burden of the Southern Baptists, a missionary school, in a sense, from the whites to the blacks. It was started in 1924, primarily to keep black Baptists from going to the white seminary in Louisville.

I was pulled into a sort of interracial setting. They had white professors on the staff, and white Baptist ministers from the city would come in for chapel. There would be visiting professors from time to time. It was just an eye-opener to go to Fisk to, say, a Christmas concert, and see the interracial climate. I think my resentment toward the dual system of segregation and racial discrimination — probably the tempo of my resentment — increased at that time. Then traveling from Nashville to Troy and from Troy back to Nashville, we were forced to go to a segregated waiting room, to sit in the back of the bus, and all that.

At that time, Little Rock was going on, September of ’57. There were many things happening, and because it was an everyday occurrence, I became very conscious of it. I spent a great deal of time during this period preaching what some people call the social gospel. I just felt that the ministry and religion should be a little more relevant. Some of my classmates would tease me about that.

Even people like James Bevel would tease me. He was a classmate of mine, a semester ahead of me. And Bernard Lafayette, who was a year behind me. We became very good friends, the three of us.*

Most of the other guys were going to some church out in the country on Sunday mornings to preach because they got a little money. When a minister would invite you to preach, they’d take up a special collection. I didn’t do much of that, but Bevel was one of these guys who would always go out and preach somewhere. In the black Baptist church, there’s a certain type of minister that is described as a “whooper.” Bevel was known as a whooper. It’s the tone of voice. Evangelist! Shouting! Some people refer to Aretha Franklin’s father C. L. Franklin as a great whooper. These guys can put music in their voice, can turn people on. Bevel went out and did a great deal of this. He was called to a little church in Dayton, Tennessee, and he would invite us to go up, and we would preach for him. And the people would fix a good meal.

During the summer of 1958, I met Dr. King for the first time. It was in Montgomery. I had an interest in withdrawing from ABT. When I look back on it — and I’ve thought about it from time to time - it was not just for the sake of desegregating Troy State University. I wanted to be closer to my family, my parents, and my younger brothers and sisters. I could stay at home and go to Troy. I got an application and had my high school transcript and my first year of study at ABT sent there. I didn’t hear anything, so I sent a letter to Dr. King, and he invited me to come to Montgomery. I took a bus from Troy to Montgomery one Saturday morning. I met with Fred Gray, Dr. King, and Rev. Abernathy and told them of my interest in enrolling at Troy State University. They couldn’t believe it. They thought I was crazy! But they were interested. They wanted to pursue the whole idea, and we had a good discussion.

I had written the letter to Troy State on my own without talking it over with my parents. I just did it really, didn’t contemplate it at all, just sent it in and applied. Later, Fred Gray sent a registered letter to Troy State saying that we hadn’t heard anything. We never got any return correspondence. Then the question came up of whether a suit should be filed against the State Board of Education, the Governor and the University. At that time, it would have involved my parents signing that suit, and they didn’t want to do it. So we had to drop the whole idea.

I went back to American Baptist in the fall and continued my studies. And then I started attending mass meetings sponsored by the NAACP. In Nashville, there was an organization at that time called the Nashville Christian Leadership Council (NCLC), which was a chapter of SCLC. They started sponsoring some meetings on Sunday night at Kelly’s church downtown.

Later, under the direction of Jim Lawson, a divinity student at Vanderbilt, NCLC started nonviolent workshops every Tuesday night. For a long period of time, I was the only student from ABT that attended. It was like a class; we would go and study the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence. There was very little discussion during the early workshops about segregation or racial discrimination or about the possibility of being involved in a sit-in or freedom ride. It was more or less a discussion about the history of nonviolence. I did sense that it was going to lead to something; we got into socio-drama — “If something happened to you, what would you do?” — the whole question of civil disobedience. And we dealt a great deal with the teachings of Jesus, not just the teaching of Ghandi, but also what Jesus had to say about love and nonviolence and the relationship between individuals, both on a personal and group basis, and even the relationship between nations.

I remember we had the first test sit-in in Nashville at two of the large department stores, Cain-Sloan’s and Harvey’s. It was an interracial, international really, group of students. We just walked in as a group and occupied the stools in one area and went to the restaurant, I think, at Harvey’s. They said that we couldn’t be served, and we got up and left, just like that. It was to establish the fact that they refused to serve an interracial group, or refused to serve blacks. We did one in November of ’59 and one in December.

During the Christmas holidays, Bernard Lafayette and I took a bus home from Nashville. Bernard lives in Tampa, so he took a bus as far as Troy with me. I’ll never forget it! We got on the bus in Nashville and got near the front. The driver told us we had to move and we refused. He just rammed his seat back, so we were in the front seat right behind the driver all the way and nothing happened. I think when we got to Birmingham, we decided to move. It was a testing period. I don’t know why we did it; it was not part of a plan or anything like that.

When we got back after the holidays, we started attending the nonviolent workshops again. At that time, Bernard started attending on a regular basis. On February first, after the sitins in Greensboro, Jim Lawson received a call from the campus minister for one of the black colleges in North Carolina. He said, “What can the students in Nashville do to support the students in North Carolina?” Jim just passed the information on.

That call didn’t really come to us in a vacuum; we were already involved in a workshop and preparing eventually for a similar action. So, in a matter of days, we called a mass meeting of students on Fisk University campus, and about 500 students showed up. That’s when we outlined the plan. It must have been a Monday night. We said on this Tuesday, or that Thursday — we tried to pick T-days since most of the students had light classes on Tuesdays and Thursdays — we would meet at Kelly’s church, First Baptist downtown and we would sit-in. We told them that we’d been going to the nonviolent workshop and went through it with them. The people who had been attending the workshops were to be the leaders, the spokesmen in charge of the different groups. We went down and sat in at Woolworth’s and Kresge’s and other 5-and-10s and drugstores like Walgreen’s that had lunch counters. It was a quiet day for the most part. That went on for a period of time.

Sometimes we’d sit for two or three hours. We’d have our books and we’d just sit quietly, doing our homework. Someone might walk up and hit us or spit on us or do something, but it was very quiet. The Movement during that period, in my estimation, was the finest example, if you want to refer to it, of Christian love. It was highly disciplined. When I look back on that particular period in Nashville, the discipline, the dedication, and the commitment to nonviolence was unbelievable.

Two or three times a week we would go and sit in. And then one particular day — it must have been Leap Year, because I think it was February 29, 1960, a Saturday morning. We met in Kelly’s church, and Will Campbell came to the meeting to tell us he had received information that the police officials would have us arrested and would let all type of violence occur. Kelly came to the church and warned there would be violence. But we said we had to go. We were afraid, but we felt that we had to bear witness. So Jim Lawson and some of the others were very sympathetic and felt that if we wanted to go that we should.

It was my responsibility to print some rules, some “do’s and don’ts,’’ what people were supposed to do and what they were not supposed to do: sit up straight, don’t look back, if someone hits you, smile, things like that. I got some paper . . . you see, I had worked for two years in the kitchen at ABT; my last two years I worked as a janitor cleaning the Administration building so I had access to office supplies. We got a secretary to type it and we used a mimeograph machine. Several of us engaged in a conspiracy to get the paper and get the rules distributed. At the end it said something like, “Remember the teachings of Jesus Christ, Ghandi, and Martin Luther King: May God be with you.” We gave them to all those people that Saturday morning.

Woolworth’s was where the first violence occurred. A young student at Fisk, Maxine Walker, and an exchange student named Paul LePrad were sitting at the counter at Woolworth’s. This young white man came up and hit Paul and knocked him down and hit the young lady. Then all type of violence started. Pulling people, pushing people over the counter, throwing things, grinding out cigarettes on people, pouring ketchup in their hair, that type of thing. Then the cops moved in and started arresting people.

That was my first time, the first time for most of us, to be arrested. I just felt . . . that it was like being involved in a Holy Crusade. I really felt that what we were doing was so in keeping with the Christian faith. You know, we didn’t welcome arrest. We didn’t want to go to jail. But it became . . . a moving spirit. Something just sort of came over us and consumed us. And we started singing “We Shall Overcome,” and later, while we were in jail we started singing “Paul and Silas, bound in jail, had no money for their bail . . .” It became a religious ceremony that took place in jail. I remember that very, very well, that first arrest.

Even after we were taken to jail, there was a spirit there, something you witness, I guess, during a Southern Baptist revival. People talk about being born again or their faith being renewed. I think our faith was renewed. Jail in a sense became the way toward conversion, was the act of baptism, was the process of baptism.

Then hundreds of students heard about the arrest. We all went to jail and hundreds of others came downtown and sat in. At the end of the day, they had arrested 98 people. During that Saturday night, lawyers and professors and the president of Fisk and other schools came down to try to get us out of jail, but we refused. We said that we would stay in jail, that we felt we hadn’t committed any wrong. They wanted to put up the bond. It was not a tremendous amount per person, but altogether it would have been up to several thousand dollars. Finally late that night or early that Sunday morning, the judge made a decision to let us out in the custody of the president of Fisk. And we all came out.

We went to trial the following Monday. The judge wanted the trials separately, but the lawyers objected. They wanted us tried as a group. They tried one case, and the guy was fined fifty dollars or thirty days in jail. At that time, we made a conscious decision that we wouldn’t pay the fine, that we would go to jail and serve our term. So we all went back to jail. The next day, Jim Bevel took a group of around 60 to the Trailways Bus Station and they all got arrested. So that was more people in jail. That process kept going on for some time.

I think the older ministers in the community — C. T. Vivian, Metz Rollins, and Kelly Miller Smith, saw themselves in an advisory role. They were leaders of the NCLC in charge of setting up the mass meetings. If we needed something, if there were funds needed to pay a fine or get someone out of jail, we could get money from them. For a place, we used Kelly’s church and Rev. Alexander Anderson’s church, Clark Memorial. They also had contacts. When we needed cars, Kelly would call some of his members to have their car at Fisk or Tennessee State in time to pick up students and bring them to his church. We depended on them for support. They were a resource.

We also got support from the United Church Women and the lady who directed the Tennessee Council on Human Relations, Katherine Jones. A group from the United Church Women would always be on the scene. A lot of times when we were involved in a demonstration in the city, we didn’t know that in the store or in the picket line, there were observers from the United Church Women. But they were there, and they were supportive. They came to the courtroom during the trial. They wrote letters and met with the merchants to try to get them to desegregate.

I once described the early civil rights movement as a religious phenomenon. And I still believe that. I think in order for people to do what they did, and to go into places where it was like going into hell fire, you needed something to go on. It was like guerrilla warfare in some communities, some of the things people did. And I’m not just talking about the students, but the community people, indigenous people. It had to be based on some strong conviction, or, I think, religious conviction.

I remember on the Freedom Rides in 1961, when we got to Montgomery . . . personally, I thought it was the end. It was like death; you know, death itself might have been a welcome pleasure. Just to see and witness the type of violence . . . the people that were identified with us were just acting on that strong, abiding element of faith.

In Birmingham, we stayed in the bus station all night with a mob, the Klan, on the outside. On the day we arrived, Bull Connor literally took us off the bus and put us in protective custody in the Birmingham City Jail. We were in the jail Wednesday night, all day Thursday and Thursday night. On Friday morning, around one o’clock ne took us out of jail and took us back to the Alabama - Tennessee state line and dropped us off. There were seven of us, an all-black group. He dropped us off and said, “You can make it back to Nashville, there’s a bus station around here somewhere.” That’s what he said. And just left us there! I have never been so frightened in my life.

We located a house where an old black family lived. They must have been in their seventies. We told them who we were and they let us in. They’d heard about the Freedom Rides and they were frightened. They didn’t want to do it, but they let us in and we stayed there. The old man got in his old pick-up truck when the stores opened and went and got some food. You see, we had been on a hunger strike and hadn’t had anything to eat. He went to two or three different places and got bologna, bread and viennas — all that sort of junk food, and milk and stuff. And we ate.

We talked to Diane Nash in Nashville, and she said that “other packages had been shipped by other means,” meaning that students had left Nashville on the way to Birmingham to join the Freedom Ride by private car and by train. We just assumed the telephone lines were always tapped. She sent a car to pick us up, and we returned to Birmingham and went straight to Rev. Shuttlesworth’st home to meet the new people. More students from Fisk, ABT, and Tennessee State had joined the ride as well as two white students from Peabody. The total number was about 21.

At 5:30 we tried to get a bus from Birmingham to Montgomery, and — I’ll never forget it — this bus driver said, “I only have one life to give, and I’m not going to give it to CORE or the NAACP.” This was after the burning of the bus at Anniston and after the beating of the CORE riders on Mother’s Day. So we stayed in the bus station. At 8:30 another bus was supposed to leave, and that bus wouldn’t go either. We just stayed there all that night. Early the next morning Herb Kaplow, then a reporter for NBC, who’s now with ABC, came to tell us he understood Bobby Kennedy had been talking with the Greyhound people and apparently we would be able to get a bus later. So we got on the bus about 8:30 Saturday morning. The arrangement that Kennedy had made was that every fifteen miles or so there would be a state trooper on the highway and a plane would fly over the bus, to take us into Montgomery. An official of Greyhound was supposed to be on the bus also, but I don’t actually recall that there was one.

I took a seat in the very front behind the driver along with Jim Zwerg. On the way to Montgomery we saw no sign of the state trooper cars or the plane. It was a strange feeling. For almost four years I had traveled that way from Montgomery to Birmingham. This time, we didn’t see anyone. It was the eeriest feeling of my life. When we reached Montgomery, we didn’t even see anyone outside the bus station. We started stepping off, and the media people began gathering around. Then just out of the blue, hundreds of people started to converge on the bus station. They started beating the camera people; they literally beat them down. I remember one guy took a huge camera away from a photographer and knocked him down with it.

People started running in different directions. The two white female students tried to get in a cab, and the black driver told them he couldn’t take white people and just drove off. They just started running down the street, and John Seigenthaler got between them and the mob. Another part of the mob turned on us, mostly black fellows. We had no choice but to just stand there. I was hit over the head with a crate, one of these wooden soda crates. The last thing I remember was the Attorney General of Alabama, serving me with an injunction prohibiting interracial groups from using public transportation in the state of Alabama while I was still lying on the ground. Yes, I was afraid. I was afraid.

Jim Zwerg was one of the most committed people, and I definitely believe it was not out of any social, “do-good” kind of feeling. It was out of his deep religious conviction. There were others who felt the same; people just felt something was wrong. You know during the workshops in Nashville we never thought or heard that much about what would happen to us personally or individually. And we never really directed our feelings of hostility toward the opposition. I think most of the people that came through those early days saw the opposition and saw ourselves, really, the participants in the Movement, as victims of the system. And we wanted to change the system.

The underlying philosophy was the whole idea of redemptive suffering — suffering that in itself might help to redeem the larger society. We talked in terms of our goal, our dream, being the beloved community, the open society, the society that is at peace with itself, where you forget about race and color and see people as human beings. We dealt a great deal with the question of the means and ends. If we wanted to create the beloved community, then the methods must be those of love and peace. So somehow the end must be caught up in the means. And I think people understood that.

In the black church, ministers have a tendency to compare the plight of black people with the children of Israel. So, I think we saw ourselves as being caught up in some type of holy crusade, with the music and the mass meetings, with nothing on our side but a dream and just daring faith. ... I tell you the truth, I really felt that I was part of a crusade. There was something righteous about it.

I really felt that the people who were in the Movement — and this may be short-sighted and biased on my part — were the only truly integrated society and, in a sense, the only true church in America. Because you had a community of believers, people who really believed. They were committed to a faith.

I was wrong, I think, to feel that way, because you shouldn’t become so definitive as to believe that you have an edge on the truth. I think you have to stay open. But, you know, in the process of growing and developing, people go through different experiences.

The Movement - its strange to say this in 1976 — but the Movement later became much more secular. The people that made up the leadership of the Southern sit-in movement during 1960 were ministerial students, or someone who came from a strong religious background. SCLC was founded primarily by ministers in the basement of Ebenezer Baptist Church.

The change toward secularization could have something to do with the Movement becoming an “in thing.” It became glamorized. It was no longer a group of disciplined students sitting down in Nashville, or a group of people traveling into the heart of Mississippi on the Freedom Rides. I think the media had something to do with it; the publicity started attracting many different types of people.

I think the Movement lost something because during the ’60s, it affirmed for us, and instilled in us, a sense of hope that change was possible. The whole idea of forgiving - I think we lost some of that. In 1961, we were not just using the non-violent principle as a tactic; it became a philosophy, a way of life. It was not just the way we treated each other, and not just for public demonstrations. It became a way. We have lost some of that “soul” — soul in the way that black people refer to soul — the meaning, the heart, the experiencing.

I think that a great deal had to do with the influx of people from the North, black and white, who had very little relationship, or any real kinship to religious foundations, or to any Southern experience. Most of the people from the South, even those that were not totally committed for religious reasons, had a deep appreciation for the role of religion and the black church. The people who came down, particularly in late ’63 and ’64, just didn’t have any appreciation for it.

There is something very special and very peculiar about the South itself; then there is also something very special and peculiar about black religious life. The church is a special place in a small town or rural community. For a lot of people in the urban centers, it is the heart of the community. It’s the only place where people can go sometimes for fellowship and worship with their friends and neighbors. But more than that, it’s a place where people can come together and sort of lay everything else aside — maybe it is the only place. And they can identify with it, and they can appreciate it.

One reason I think the Movement itself was so successful — and Dr. King as leader, as a symbol — in mobilizing so many people was that it built on strong and solid religious ground. In a sense Dr. King used the black church, and the emotionalism within the black church, as an instrument to move people toward their own freedom. People believed there must be something right about the Movement when its mass meetings were held in the church.

I still consider myself a very hopeful and optimistic person in spite of all the bad things that happened since 1960. . .the assassinations. Sometimes I look back on all those funerals that I went to, people that I knew and loved, the war and all, but I’m still hopeful. You know, Dr. King used to say when you lose hope, it is like being dead. You have to have that element of faith and hope; you have to be based and grounded in something.

I do not hide or try to get away from the fact that I am a licensed, ordained Baptist minister; I am a minister. But on the other hand, I don’t see myself going to a pulpit every Sunday morning and preaching; I just don’t see that as my role. I feel I can make a greater contribution and do the greatest good by doing what I am doing now. When I go out and tell people to register and vote, I tell people that they should have some control over their lives, that they should organize if they want to get a sewage system, or if they want to get food stamps or want to do something about welfare. Or if they think this man is doing them wrong, they should come together and get someone else.

I see what I am doing now as a continuation of the early Movement, and based on the same principles. One of the things I say to black elected officials and white elected officials is that what we need to do from top to bottom in this country is to inject a sense of morality into a viable politics. I think that is what is missing in the political arena and to some degree, I guess, in what is remaining of the Movement. We have lost that sense of ethic, that sense of morality — that you do something because it is right.

You know, I stopped going to church for a while; I did. Not out of ... I don’t know, I just stopped going for quite a few years. But these days I find myself going back.

I think the churches today are still relevant; I think there is a need for the institution. On the other hand, I think the church, black and white, is far, far behind. The leadership of the church is out of step. I do feel that in this country, particularly in the urban centers, if we continue to get property and build these fantastic buildings, that the day may well come when the next struggle will not be directed toward the secular institutions, but toward the church.

And the church may well deserve that. You have churches with a great deal of wealth; individual churches and religious bodies that own tremendous amounts of land and resources when all around them there is poverty and hunger. The churches are far, far behind.

I think the white church and the black church will remain apart for years to come. The leadership of the black church is perhaps much more socially conscious, much more political, much more involved in the life of the community. They really don’t separate the condition around them from the church; for the most part, that is an exception. I think the black church could do more, but I think the black church is much farther down the road than the white church. Black ministers have been leaders; they have been taking the initiative, whether it is in politics, or trying to make the economic conditions better. When you look around the South, at places like Mississippi and south Georgia, and the number of black churches that were bombed and burned down during the early ’60s, it is a testimonial. Something was happening there.

In another sense, particularly in the black Baptist church, I think religion is much more personal. It dominates the lives of people. The whole concept of Jesus, as a brother or king, is much more personal. Whether people are working in the kitchen, or the field or whatever, religion takes on a personal quality.

I don’t see a great marriage anytime in the near future between the white church and the black church. You know people say eleven o’clock on Sunday morning is the most segregated hour of the week, and it still is. I think that will be true for years and years to come. Yeh. It’s strange. The history of it is really strange.

Tags

John Lewis

Jim Sessions

Sue Thrasher

Sue Thrasher is coordinator for residential education at Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee. She is a co-founder and member of the board of directors of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1984)

Sue Thrasher works for the Highlander Research and Education Center. She is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. (1981)