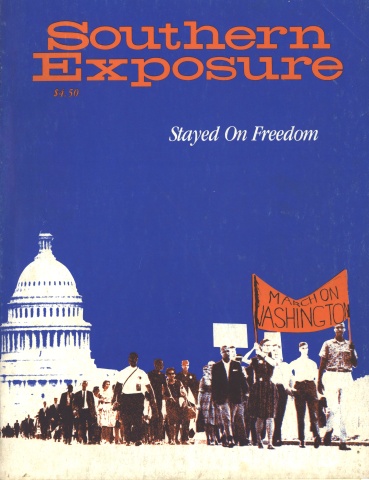

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

In the winter of 1960, the nation was mesmerized by a group of young black college students in Nashville, Tennessee, who appeared at a segregated lunch counter one Saturday afternoon and asked to be served. All that spring, they filled the jails and the nation with their freedom songs, sparking similar actions and demonstrations across the South. Although an earlier sit-in had been held in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February 1, 1960, it was the small coterie of Nashville students who gave impetus to the concept of nonviolent direct action and who continued through the next years to provide critical leadership to SNCC, SCLC, CORE and the Movement in cities throughout the nation. Among those students who had been meeting for months discussing the religious, ethical and tactical basis of nonviolent civil disobedience were Jim Lawson, Diane Nash, James Bevel, Bernard Lafayette, Marion Barry and John Lewis.

Jim Lawson’s remarks here were published in the Southern Patriot shortly after he had been expelled from Vanderbilt Divinity Schoolfor his protest activity; the Reverend Lawson is now a pastor in Los Angeles, California. Marion Barry, now mayor of Washington, DC, was interviewed in 1967 for Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center. The John Lewis interview, conducted by Jim Sessions and Sue Thrasher, is excerpted from a longer section of Southern Exposure’s new book, Growing Up Southern, published by Pantheon Books in July, 1981. Lewis, who was chairman of SNCC for several years and then director of the Voter Education Project, now works for the National Consumer Cooperative Bank.

Barry

I was in graduate school at Fisk for two years, 1958 to 1960. I went to high school in Memphis and college at LeMoyne in Memphis, and graduated in 1958 with a bachelor of science in chemistry. Then I went to Nashville. In the latter part of 1959, Jim Lawson was holding discussions on nonviolence and how it’s applicable in America. I’d never heard of nonviolence before then. I’m not a pacifist; I wasn’t then. This was all new to me.

We had discussions, meetings every week. In early December, we talked about going down to various department stores, having a sit-in, trying to get served way back then. We had planned to do some testing of it before January and then start a program sometime in February or March. We were meeting on this and then February first happened in Greensboro, North Carolina. People in Greensboro were calling people, and it had spread after that first week to Durham, to Raleigh, all around in North Carolina. By the thirteenth, a lot of cities broke out with sit-ins and some arrests, some violence on the part of the white folks. So that whole weekend people around the country started moving.

That’s when I started working with Diane [Nash] and Bevel and others to form a central committee in Nashville as the “core” of the Movement there. We planned strategy and demonstrated the next weekend. Then, I think it must have been the twenty-seventh of February, there was a large number of people arrested. I was arrested in that group with Bevel and Diane at Woolworth’s or Kresge. This is where Paul LePrad, who was a white student, got beat pretty badly. It was on national television and a big thing. He was one of the three or four white people joining in. For Nashville this was a very significant thing that you have white people joining blacks on anything like that.

Nashville, you know, sort of got it all out of proportion because it was sort of unusual that it would happen in Nashville. Secondly, you had a large number of Fisk and Tennessee State students involved, which was sort of unusual because Fisk is, traditionally, supposed to be one of the elite Negro schools.

At that time, Stephen J. Wright was the president. We got arrested on Saturday. We got out about 11 or 12 o’clock that Saturday night. We all went back to the campus singing freedom songs and everybody was waiting. They didn’t go partying that night. They waited until we got out and came down. The next day we’d called a mass meeting for the chapel to inform students what was going on. President Wright said he wanted to address the students. We were a little reluctant because we didn’t know what he was going to say. We didn’t know whether he was going to say, “You all ought to stop all this mess. This is bad.”

So we said, “Well he’s going to say it at some point. We might as well let him say it now so we can have a chance to refute or to counteract anything he says right there on the spot.”

We had a number of speakers; students spoke and then President Wright spoke. He supported the whole thing. He said it was the kind of thing that students had to do, that he would do all he could to help and that Fisk University would do all it could to help, which was very encouraging. That was the first time in many months that he had gotten a standing ovation from anybody because, as I understand it, he wasn’t very popular with the faculty or the students.

This was the first time a number of us had ever been arrested. It was certainly my first arrest. We had talked about going to jail and about making sacrifices, some things being necessary. I didn’t feel anything about it. In jail I wasn’t frightened. The only thing that happened was we were all packed in and we didn’t like that. As far as jail, that was no big thing.

The night we got out, that Saturday night, we had an all-night meeting with lawyers. We said that we wanted to go back to jail and stay in. The whole thing was how do you plead. Do you plead guilty, not guilty, or what do you do? We said, “We’ll plead not guilty and if we’re found guilty we’ll go back and spend whatever time is necessary in jail.” The NAACP lawyers said, “Don’t do that. That’s not right. We’re going to appeal it. Just get out. Just go down there.” So we finally said, “We’re going to do it.” They said, “Well, if you’re going to do it, well, we’ll just have to be there to help you do it.” So we said, “We’re going to do it with or without you. We’ll go down and plead our case.”

We didn’t want to pay the city any money. Second, we figured even at that point that being in jail would be a dramatization of what was going on and that just the little time that we had been in on Saturday, the community had come forth and put up about $50,000 worth of bonds to get us out that Saturday night — mortgaged their land and houses, and given us cash, savings accounts and things. This was significant for Nashville.

So on Monday night we went down and everybody pleaded not guilty. They tried one person for, I guess, half the day and they finally found him guilty. He said, “I’ll go to jail,” which sort of shook up the judge and the city officials. They didn’t expect that. So they fined him $50. We all decided to go to jail. So, one after another, we just started going back to jail.

After that they used the same evidence. They stood up and said, “Not guilty.” And they said, “We use the same evidence and fine you $50.” Everybody went on back to jail. I think we stayed in jail that Monday night. That Tuesday they had some more trials and more people came on in jail.

On Tuesday, they put us out to work. We refused to work. On Wednesday, they had another demonstration. About a hundred people got arrested that Wednesday. So they brought them into the jail. We were in jail, I guess, until Thursday, when they reduced our sentences and let us out.

We kept demonstrating every week. In fact, we started every day: constant demonstrations, picket lines downtown, sit-ins. We moved from about four or five stores to about 20 stores. We started a “hit-and-run” tactic where we’d go into a store; they’d ask us to leave. They closed. When you walked in, they’d close the lunch counter down. We’d leave and go to another store, and they’d ask us to leave, and we’d come back to the other store where they asked us to leave the first time. We just kept a constant thing going where we didn’t get anybody arrested, but it kept the store closed. In fact, a number of places took their stools out of their counters. We were picketing and then we had a boycott of downtown. That really hurt them because a lot of Negroes really participated in that boycott.

Lewis

The Movement during that period, in my estimation, was the finest example, if you want to refer to it, of Christian love. Sometimes we’d sit for two or three hours. We’d have our books and we’d just sit quietly, doing our homework. Then someone might walk up and hit us or spit on us or do something, but it was very quiet. When I look back on that particular period in Nashville, the discipline, the dedication and the commitment to nonviolence was unbelievable.

Two or three times a week we would go and sit in. And then one particular day — it must have been leap year, because I think it was February 29, 1960, a Saturday morning — we met in Kelly’s Church, and Will Campbell* came to the meeting to tell us he had received information that the police officials would have us arrested and would let all types of violence occur. Kelly came to the church and warned there would be violence. But we said we had to go. We were afraid, but we felt that we had to bear witness. So Jim Lawson and some of the others were very sympathetic and felt that if we wanted to go that we should.

It was my responsibility to print some rules, some “dos and don’ts,” what people were supposed to do: sit up straight; don’t look back; if someone hits you, smile; things like that. At the end it said something like, “Remember the teachings of Jesus Christ, Ghandi and Martin Luther King: may God be with you.” We gave them to all those people that Saturday morning.

Woolworth’s was the place where the first violence occurred. A young student at Fisk, Maxine Walker, and an exchange student named Paul LePrad were sitting at the counter at Woolworth’s. This young white man came up and hit Paul and knocked him down and hit the young lady. Then all types of violence started. Pulling people, pushing people over the counter, throwing things, grinding out cigarettes on people, pouring ketchup in their hair, that type of thing. Then the cops moved in and started arresting people. That was my first time, the first time for most of us, to be arrested. I just felt . . . that it was like being involved in a Holy Crusade. I really felt that what we were doing was so in keeping with the Christian faith. You know, we didn’t welcome arrest. We didn’t want to go to jail. But it became ... a moving spirit. Something just sort of came over us and consumed us. And we started singing “We Shall Overcome,” and later we started singing “Paul and Silas bound in jail, had no money for their bail. . . .” It became a religious experience that took place in jail. I remember that very, very well, that first arrest.

Even after we were taken to jail, there was a spirit there, something you witness, I guess, during a Southern Baptist revival. I think our faith was renewed. Jail in a sense became the way toward conversion, was the act of baptism, was the process of baptism.

I was afraid. I was afraid.

You know, during the workshops in Nashville, we never thought or heard that much about what would happen to us personally or individually. And we never really directed our feelings of hostility toward the opposition. I think most of the people that came through those early days saw the opposition — and saw ourselves, really, the participants in the Movement — as victims of the system. And we wanted to change the system. People just felt something was wrong.

The underlying philosophy was the whole idea of redemptive suffering — suffering that in itself might help to redeem the larger society. We talked in terms of our goal, our dream, being the beloved community, the open society, the society that is at peace with itself, where you forget about race and color and see people as human beings. We dealt a great deal with the question of the means and ends. If we wanted to create the beloved community, then the methods must be those of love and peace. So somehow the ends must be caught up in the means. And I think people understood that.

In the black church, ministers have a tendency to compare the plight of black people with the children of Israel. I think we saw ourselves as being caught up in some type of holy crusade, with the music and the mass meetings, with nothing on our side but a dream and just daring faith. ... I tell you the truth, I really felt that I was part of a crusade. There was something righteous about it.

I really felt that the people who were in the Movement — and this may be short-sighted and biased on my part — were the only truly integrated society and, in a sense, the only true church in America. Because you had a community of believers, people who really believed. They were committed to a faith.

I was wrong, I think, to feel that way, because you shouldn’t become so definitive as to believe that you have an edge on the truth. I think you have to stay open. But, you know, in the process of growing and developing, people go through different experiences.

* “Kelly’s church” was the First Baptist Church, pastored by Kelly Miller Smith, the president of the Nashville Christian Leadership Council. Will Campbell was then working with the National Council of Churches in Nashville.