The Murder of Joseph Shoemaker

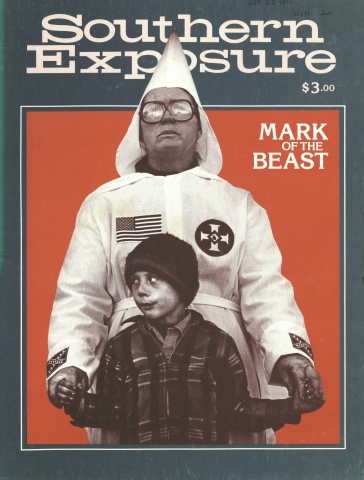

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

On November 30, 1935, at about nine o’clock in the evening, a group of Tampa policemen, without a warrant, entered a home at 307 East Palm Avenue and seized six men who were holding a political meeting. After a brief interrogation, the men were released, but three of them — Eugene F. Poulnot, Sam Rogers and Joseph Shoemaker — were abducted by a gang waiting in cars outside police headquarters. These three, all unemployed, and known for their opposition to the city administration, were taken to a wooded area some 14 miles from Tampa. There they were undressed and flogged, after which hot tar and feathers were applied to the wounds. The three were then warned to “get out of town in 24 hours or we’ll kill you.” Poulnot and Rogers were able to make their painful way back to Tampa, but Shoemaker, who had suffered the worst beating, collapsed and spent the night in a ditch alongside a deserted country road. The following morning, Shoemaker’s friends found him and rushed him to a hospital. According to one of the doctors, “He is horribly mutilated. I wouldn’t beat a hog the way that man was whipped. ... He was beaten until he is paralyzed on one side, probably from blows on the head. ... I doubt if three square feet would cover the total area of bloodshot bruises on his body, not counting the parts injured only by tar.” In a desperate attempt to save Shoemaker’s life, doctors amputated his left leg, but to no avail. The victim died on December 9, nine days after the flogging.

Radicals and union organizers have frequently encountered defeat in the South. However, the setbacks for labor and the left have not been due to their inability to attract a following among Southern workers. Indeed, some of the most radical mass movements in America, such as the Populist Party and the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, had Southern roots. The Ku Klux Klan and other violent vigilante groups, often encouraged and aided by more “respected” members of their communities, have played a continuing role in repressing these progressive movements.

Vigilante violence has erupted in every section of the country, but it has proved especially popular in the South. This is particularly true when the challenge to the status quo comes from peaceful groups operating within the law. Faced with this situation, defenders of the local establishment often resort to violence as an illegal but effective way of eliminating “undesirables.”

In a few cases during the 1930s, vigilantes created formal organizations that were widely publicized. In Atlanta, for instance, a group calling itself the Black Shirts carried on a brief campaign of threats against workers. A self-styled White Legion was behind much of the anti-labor violence in Birmingham.

The best known of the many vigilante organizations was, of course, the Ku Klux Klan. The KKK had a relatively small following during the Depression years, but in some areas of the South it was still the chief enforcer of the established order — which excluded industrial unions and radical politics. The Klan also tried to revive its fortunes through appeals to antilabor and anti-communist sentiment.

The worst outbreak of Klan antilabor violence came in Tampa. Long a center of KKK activity, Tampa also experienced a variety of anti-radical confrontations. In 1931, over half of Tampa’s 10,000 cigar workers joined a Communist union, the Tobacco Work- . ers Industrial Union. City fathers went to the rescue of cigar manufacturers in a union-busting campaign that included police raids, arrests, a sweeping federal court injunction outlawing the union, and deportation proceedings against alien radicals. All this was backed up by vigilante action. One of the Communist organizers, Fred Crawford, was kidnapped and flogged. Leading Tampans also formed a “secret committee of 25 outstanding citizens” to help cigar owners “wash the red out of their factories.” Under these pressures, the workers’ Communist union was broken.

Four years later another radical movement emerged in Tampa. This time it was led by unemployed socialists who formed a political party, the Modern Democrats, to challenge the city’s corrupt political machine. In the 1935 municipal election, the Modern Democrats fielded a slate of candidates who ran on a socialist platform calling for reforms such as public ownership of utilities. The Modern Democrats went down to defeat in the election, but they continued to organize and demonstrate on behalf of workers and the unemployed. The kidnapping and flogging of Eugene Poulnot, Sam Rogers and Joseph Shoemaker, all leaders of the Modern Democrats, followed the election by several weeks.

As soon as the papers carried the news of the attack on the three Modern Democrats, several national groups demanded that the floggers be punished. In the first report of the attack by the Associated Press there was no hint of police complicity, but Tampa’s two newspapers quickly learned from Eugene Poulnot that he had recognized a policeman among the mob. Fearing that Tampa authorities would not vigorously pursue the case, friends of the victims appealed for help from national organizations. Norman Thomas and the Socialist Party took the lead since Poulnot and Rogers were members, and Shoemaker had been a former member. To focus attention on the case, socialists in New York organized the Committee for the Defense of Civil Rights in Tampa, a coalition headed by Norman Thomas and supported by socialist groups and unions. They began a fund-raising and letter-writing campaign designed to “bring down upon the heads of government in the city of Tampa the full force of public indignation everywhere.” The American Civil Liberties Union offered a $1,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the guilty persons. Additional support came from the American Federation of Labor (AFL) which had scheduled its 1936 convention for Tampa. Following Shoemaker’s death, William Green, the president of the union, issued a statement saying it was “altogether probable” that the group would transfer its convention to another city unless those involved were tried and, if found guilty, punished.

As pressure mounted, many Floridians condemned the floggings. In communities across the state, newspaper editors deplored the crime. The Tallahassee Daily Democrat found the crime “so revolting that no civilized community or state can permit it to go unpunished.” The Miami Herald declared the mob responsible “as venomous as a mad dog, and its leaders should be dealt with just as dispassionately as we would a rabid animal.” The Tampa Tribune reported: “No crime in the history of Hillsborough County has brought so great a clamor for punishment of the guilty.” The city’s papers joined in the rising tide of protest by giving front-page coverage to the case. Numerous editorials argued that the city “must ferret out and punish the perpetrators of this outrage.” Resolutions deploring the crime and calling for action came from many local groups including labor unions, the Junior Chamber of ComPallbearers carrying the body of Joseph Shoemaker. merce, the American Legion and the Hillsborough County Bar Association. On the Sunday afternoon following Shoemaker’s death, Tampa’s leading ministers held a public memorial service in the municipal auditorium which was attended by about 1,000 people and was broadcast over a local radio station. Walter Metcalf, pastor of the prestigious First Congregational Church and the head of the local Ministerial Association, became chairman of a group calling itself the Committee for the Defense of Civil Liberties in Tampa, which pledged cooperation with other organizations in the campaign to ferret out and punish the floggers.

A number of reasons help explain this public outcry. Although similar in some ways to other acts of mob violence that went largely unnoticed at the time, the Tampa case had several unusual features. As the New Republic observed, “When Southern white men lynch a Negro, that’s not news. When Southern white men, under the eyes of local police and apparently with tacit approval, kidnap a white man and beat him so badly he dies, that is perhaps something else again.” The nature of the crime resulting in Shoemaker’s death undoubtedly stirred many people. As one newspaper pointed out, “Even calloused minds might flinch from a thing so horrible — tar and feathers, a gangrenous leg, amputation and death that closed mumbling lips.” The citizens of Tampa also saw their city’s reputation on trial, this incident was only the latest in a series of lawless acts. Since 1931, at least three labor organizers had been beaten in Tampa, and a variety of violence had plagued recent city elections. Therefore, in the wake of the flogging of the three Modern Democrats, the Tampa Tribune warned: “Tampa cannot afford to ‘pass up’ this latest outbreak of local lawlessness.”

By 1935, Tampa was a growing urban community with a population of some 100,000 people. Its port was particularly active, exporting citrus and phosphates. Tampa’s main business was cigar-making, which produced a net profit of $273,000 on almost $10,000,000 in sales during 1935. However, Tampa’s richest source of profits may well have been gambling. In a 1935 study of this well-organized but illegal business, the Junior Chamber of Commerce estimated that the numbers racket, known locally as “bolita,” took in over $1,000,000 a month and employed approximately 1,000 people. Exposing what it branded “Our Biggest Business,” the Tampa Tribune reported that the peak load on the local telephone service came around nine o’clock in the evening when the players called to find out the lucky number for the day. Syndicates which controlled Tampa’s gambling allegedly insured a steady flow of illicit profits by paying local authorities for protection. As a result, public office could prove highly rewarding, and Tampa politics degenerated into battles to determine which faction would win access to the graft. Although difficult to document, this view of Tampa was widely held.

The 1935 municipal primary revealed Tampa politics at its worst. Since the so-called “White Municipal Party” had long governed the city, victory in the primary was tantamount to election. In 1935, two political factions bitterly fought for control of Tampa’s city government. The primary resulted in victory for the incumbent Robert E. Lee Chancey administration, but at a heavy price. Two men were shot, and over 50 people — including city employees — were arrested for stuffing ballot boxes. On the morning after the primary, the Tampa Tribune warned: “Tampa must get away from this sort of thing — when, with no important issue or interest at stake, the selfish rivalry of competing factions of politicians and of grasping gambling syndicates, each fighting for control of the offices and the lawbreaking privileges, can involve the city in a heated, disrupting and discreditable fight such as we experienced yesterday.”

One close observer of the primary was Joseph Shoemaker, who served as a poll watcher for the city administration. Disturbed by what he saw, Shoemaker organized a new party to challenge the city machine in the November general election. Although he had moved to Florida only a few months earlier, Shoemaker had been active in the Socialist Party in Vermont until he was formally ejected in 1934 for endorsing the New Deal and Democratic Party candidates. In Tampa he created a party called the Modern Democrats, dedicated to “production for use instead of profit.” Drawing on the ideas of moderate socialists such as Upton Sinclair, Shoemaker explained the platform of the Modern Democrats in a series of letters published by the Tampa Tribune. He called for a 10-point program including public ownership of utilities, free hospital care for the needy, monthly investigations of city departments, an effective referendum law and a system whereby the unemployed could produce goods for their own use. He promised a “new deal” for Tampa if voters elected Miller A. Stephens, a mechanic who was the mayoral candidate of the Modern Democrats. In addition, the party offered a candidate for tax assessor and another for the board of aldermen.

Shoemaker’s Modern Democrats picked up the support of local socialists, especially those in the Workers’ Alliance, a national organization of relief workers which had strong ties to the Socialist Party. It also had the support of the American Federation of Labor. Florida’s branch of the Workers’ Alliance was headed by Eugene Poulnot, an unemployed pressman who had been labeled a troublemaker by local authorities. After the flogging of Poulnot and his two political allies, Mayor Chancey remarked: “From the time Tampa’s local Relief Work Council was organized in 1931 and until the present time, Eugene Poulnot has been an agitator, consistently trying to stir up strife among relief clients.” Poulnot’s activities included organizing the Unemployed Brotherhood of Hillsborough County and leading demonstrations for higher relief payments. At one such rally in 1934, he was arrested by the police and charged with a breach of the peace after allegedly telling a crowd of fellow relief workers: “If they don’t give us the relief we want, let’s go open a warehouse and take what we need.” The charge was subsequently dropped, and Poulnot continued his work on behalf of the unemployed. As Socialist Party members, both Poulnot and his close friend, Sam Rogers, campaigned for the Modern Democrats.

Although their candidates were defeated in November, 1935, the Modern Democrats remained active. They held rallies and formed a permanent organization in preparation for county and state elections the following year. Shoemaker also continued to have his letters published in the Tampa Tribune. He used them to explain a new cooperative system based on the ideas of the American Commonwealth Federation. His last letter, offering to debate this plan with anyone at any time, appeared four days before he and his friends were kidnapped and beaten.

In its first public statement, the national Committee for the Defense of Civil Rights in Tampa declared: “The man who was murdered and his friends who were tortured and kidnapped were marked for only one reason: they had the courage to organize workers and to oppose a corrupt and tyrannical political machine. They took seriously their rights as workers and citizens and by their activity became undesirable to certain persons in the community of Tampa.”

Official investigations of the crime lent credence to these charges. Tampa authorities initially reacted to accusations of police complicity by attempting a coverup. After a two-day inquiry, Tampa’s chief of police, R. G. Tittsworth, reported that “no member of the police department had any participation directly or indirectly with the flogging.” Although the city seemed reluctant to press the case, county and state officials, under orders from Governor David Sholz, pushed ahead. The sheriff of Hillsborough County, J. R. McLeod, had no political ties to the city administration. Formerly a Tampa newspaperman and district director of the Works Progress Administration, McLeod had been recently appointed to office by Governor Sholz, who had dismissed the previous sheriff for “drunkenness, incompetency and neglect of duty in office.”

McLeod and state attorney J. Rex Farrior began collecting evidence. As they proceeded with their investigation, McLeod and Farrior revealed pieces of incriminating evidence that indicated the attack was premeditated. Evidence showed that one of the six Modern Democrats originally picked up by the police was John A. McCaskill, a city fireman and the son of a policeman. A recent convert to the cause of the Modern Democrats, McCaskill had briefly left the fateful meeting on November 30 in order to find Poulnot, who had not yet appeared. Shortly after Poulnot arrived with McCaskill, the police carried all six Modern Democrats to headquarters, where their names were entered in the detention book. However, McCaskill’s name was later obliterated and a fictitious one substituted. As evidence of police involvement mounted and demands for arrests increased, local officials were forced to take action. On December 9, the day of Shoemaker’s death, Mayor Chancey started his own inquiry, and he threatened to discharge any police officer who withheld information. A week later, Sheriff McLeod and state attorney Farrior began presenting evidence to a grand jury. Mayor Chancey then suspended city fireman J ohn McCaskill. The mayor also suspended the five city policemen and two special policemen who had allegedly raided the meeting of the Modern Democrats without a warrant. The following day, December 18, five of the seven policemen were arrested and charged with the premeditated murder of Joseph Shoemaker. The list of charges was later expanded to a total of six, including the kidnapping and assault of Poulnot and Rogers. A sixth person indicted was another policeman who had been tried and found innocent of vote fraud in the September primary. With the announcement of these indictments, Chief of Police Tittsworth announced that he was taking an indefinite leave of absence. A month later he was indicted as an accessory after the fact for attempting to block investigation of the crime.

Meanwhile, additional evidence had been uncovered that pointed to the participation of the Ku Klux Klan in the crime. Joseph Shoemaker’s brother revealed that shortly before the flogging he had received a telephone call with the warning: “This is the Ku Klux Klan. We object to your brother’s activities. They are communistic. Tell him to leave town. We will take care of the other radicals, too.”

The Tampa Tribune printed a copy of a Klan circular that was widely distributed in the wake of the brutal attack. Declaring “Communism Must Go,” the leaflet proclaimed, “THE KU KLUX KLAN RIDES AGAIN.” The Klan pledged “to fight to the last ditch and the last man against any and all attacks on our government and its American institutions.” The circular concluded with an appeal for help and gave a Tampa post office box as a mailing address. Three days after publication of this leaflet, Sheriff McLeod arrested two Klan members from Orlando and charged them with assaulting Shoemaker. Another Orlando man was subsequently taken into custody and also charged with participating in the flogging. According to McLeod, all three Orlando men were Klan members who had served as special policemen in Tampa’s September primary. The indictment of a police stenographer, as an accessory after the fact, brought to 11 the number of persons charged in the flogging case. At one time or another, all 11 had been employed by the Tampa police department. The eight who worked for the city at the time of the flogging were part of the local establishment, although none, except perhaps Police Chief Tittsworth, could be considered a member of the community’s elite.

Prominent Tampans went to the aid of the accused. The chief defense attorney was Pat Whitaker, Mayor Chancey’s brother-in-law, who was widely considered as a possible candidate for governor in 1936. Bail bonds for the accused, amounting to almost $100,000 in all, were provided by a group of local businessmen, including Eli Witt, owner of Hav-A-Tampa Cigar Company; D. Hoyt Woodberry, secretary-treasurer of Hav-A-Tampa; E. L. Rotureau, president of Tampa Stevedoring Company; and Edward W. Spencer, owner of Spencer Auto Electric, Inc.

The indictment of the policemen brought praise from Norman Thomas, the perennial candidate for president on the Socialist Party ticket. On Sunday, January 19, 1936, Thomas arrived in Tampa, where he spoke to a cheering crowd of 2,000 people at a rally sponsored by the local Committee for the Defense of Civil Liberties in Tampa. Thomas attacked the “men higher up” who “protect and maybe order [floggings]; the politicians who profit by such things; the economic interests who are intent upon putting fear in their workers.” Yet he praised Tampans also. “This is the first time in American history,” he declared, “that any floggers ever have been brought to justice, and perhaps some of the higherups reached.” He attributed the indictments to the courageous efforts of Reverend Metcalf, Sheriff McLeod, the Tampa Tribune and the Tampa Times.

Seven of the accused policemen went on trial in March, 1936. Defense lawyers won a change of venue to Bartow, in neighboring Polk County, because they believed that the extensive publicity would make it difficult to find an impartial jury in Tampa. Six of the seven defendants were charged with four counts each relating to the kidnapping of Eugene Poulnot. Former Police Chief Tittsworth was charged with being an accessory after the fact. Prosecution witnesses, including Poulnot and several policemen, identified five of the defendants as participants in the kidnapping that had occurred in front of police headquarters. The police officers who testified for the prosecution testified that they had originally concealed the facts of the case because they feared they would lose their jobs if they told the truth. However, after Tittsworth stepped down as police chief, they had told prosecutors all they knew. In crossexamination defense attorneys tried to paint prosecution witnesses as liars or communists. Asserting that “communism stands for social equality of all races,” a defense lawyer made the point that police raiding the meeting of the Modern Democrats had seized a picture showing a white man and a black man shaking hands under the caption, “Equalization.” In rebuttal, prosecutors exhibited records which showed that the Modern Democrats advocated change through legal political methods. Furthermore, minutes of their meetings disclosed that they regularly sang “America” and read excerpts from the United States Constitution.

At the end of the long six-week trial the defense presented its case. It first moved for a directed verdict of acquittal which Judge Robert T. Dewell granted for two defendants, the former police chief and Robert Chappell, a policeman, whom no one had directly linked to the kidnapping. Judge Dewell also reduced the charges against the remaining five defendants by eliminating counts related to an alleged conspiracy to kidnap Poulnot. Left with a single charge of kidnapping, the defense provided only 27 minutes of testimony, all designed to attack the credibility of Poulnot. In final arguments to the jury, the prosecution appealed for conviction in order to preserve the constitutional rights of free speech and freedom of assembly. Pat Whitaker claimed that the real issue was the communist threat to Anglo-Saxon civilization.

In a surprise decision, the six-man jury returned verdicts of guilty. The outcome astounded the defense and prosecution alike, because no one had expected any local jury to convict in such a case. But the jurors, who deliberated less than three hours, told reporters there was no question in their minds. One juror commented, “Communism and all that stuff had nothing to do with the case.” Another, a former deputy sheriff, declared: “What got us was the way those policemen, supposed to be the law enforcement officers, went right out and participated in an unlawful act.” Each of the five policemen was sentenced to a four-year prison term, but was released on bail pending appeal.

Many observers believed that the guilty verdicts represented a turning point in Florida justice. The American Civil Liberties Union hailed the convictions as “a victory in the fight for civil rights in Florida and the beginning of a drive against the Ku Klux Klan.” A socialist newspaper called the jury decision “the most stunning blow against vigilantism ever struck in Florida.” However, this journal warned its readers that the trial was only the first round in the fight for civil liberties because the “convicted kidnappers may still be cleared by legal maneuvers in the Florida Supreme Court.”

This suspicion proved correct. On July 1, 1937, over a year after the guilty verdicts were handed down, Florida’s highest tribunal overturned the convictions because the trial judge had failed to inform the jury that it could not consider evidence related to the charges of conspiracy to kidnap which the judge had dismissed. Therefore, the Florida Supreme Court ordered a new trial for the five policemen who had been found guilty of kidnapping Poulnot. While awaiting retrial on the charge of kidnapping, the five defendants were prosecuted in October, 1937, for the murder of Joseph Shoemaker. After severely limiting the admissible evidence, the same trial judge, Robert Dewell, directed verdicts of acquittal. In June, 1938, a retrial on the kidnapping charge resulted in a jury finding of not guilty.

The apparent success of vigilantism encouraged its further use in Tampa. Although the Modern Democrats disappeared, vigilantes continued to violate the civil liberties of radicals and labor organizers. During the period of 1936 to 1938, the American Civil Liberties Union annually ranked Tampa as one of the worst “centers of repression” in the United States.

The flogging case indicates that the violence in Tampa was not random or meaningless. On the contrary, it was a systematic, though illegal, method of protecting the existing order from any perceived threats, even legal ones. As such, the failure to punish the vigilante murderers of Joseph Shoemaker remained, in the words of the Tampa Tribune, “a grim and ineradicable indictment of Florida, its courts, its citizenship .”

Tags

Robert P. Ingalls

Robert Ingalls is the managing editor of Tampa Bay History, which devoted its latest issue to the history of Ybor City. (1986)

Robert P. Ingalls teaches history at the University of Florida in Tampa. (1984)

Robert Ingalls is an associate professor of history at the University of South Florida, Tampa. A fuller account of the Tampa flogging case appeared in The Florida Historical Quarterly, July, 1977. (1980)