This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 2, "Sick for Justice: Health Care and Unhealthy Conditions." Find more from that issue here.

Like the Rossville Health Center, Kentucky’s Mud Creek Citizens Health Project was preceded by a history of political struggle. In the mid-1960s, the residents of Mud Creek organized the East Kentucky Welfare Rights Organization (EKWROJ to address such issues as school lunches in Floyd County, strip mining, and miners’ benefits, especially black lung. From the start, a very significant portion of their time was spent on health issues in Floyd County, and EKWRO achieved national attention in its attempt to reform the Floyd County Comprehensive Health Services Program. Despite its name, the OEO-funded health program provided no direct health services to people. Instead it served as a referral mechanism to local doctors, provided transportation for eligible clients and reimbursed local doctors for service to people unable to pay. When attempts failed to gain broader and more active representation of poor people on the board and a more comprehensive health program, EKWRO worked to cut off OEO support. Eventually in 1971, the Office of Health Affairs of OEO suspended funding for the program. It then worked out a compromise with local officials to create a new program, the Big Sandy Comprehensive Health Program which is still operating with support from HEW.

In 1973, several members of EKWRO, including Eula Hall, helped establish a clinic in 1973 on Tinker Fork under direct community control. The following interview makes clear that meeting the health needs on Mud Creek has been a continuing struggle. One constant problem has been the lack of available and willing physicians: without a doctor, the clinic cannot be reimbursed by federal programs for non-paying patients. There are other reasons for the difficulty in meeting the expenses at this and other community clinics. Fewer rural Southerners have health insurance available to them than any other group in the nation. Nearly half the people in the South who live on farms were without health insurance in 1968, and almost a third of those living in nonfarming, nonmetropolitan areas - like Mud Creek - were without it as compared to 36.8 percent and 24.2 percent nationally. Health insurance is most often provided as a fringe benefit to employees of large companies or workers with a union; consequently, where you find low-paying work and nonunion labor, you find less health insurance.

Medicaid is another problem: in 1970 only thirty-eight percent of the children in below-poverty families in Kentucky received Medicaid services at an average cost of $76, compared with the corresponding national figures of fifty-five percent and $126. Kentucky Medicaid pays only a portion of the charge for service and prohibits a provider from charging a Medicaid patient for the rest. Consequently, a community clinic loses money, under this arrangement, in treating a Medicaid patient.

Since the 1950s, the United Mine Workers Health Fund has been the predominant form of health insurance available to patients of the clinic, providing the facility with an average $5,000 each month. On July 1, 1977, the Fund abandoned this retainer system and instituted a fee-for-service system in which the Fund paid sixty percent of charges, and the patient, forty percent.

The following interview was conducted on July 28, 1977, when the Fund’s policy change had already made its impact. But the clinic has continued to provide care for those who need it, whether or not they can pay, and has been near financial ruin as a result. The problem is compounded by the wildcat strikes which have left miners’ families with no income to pay for health care. Despite a plethora of programs such as Medicaid and Medicare that are supposed to “cure”rural health ills, in reality the clinic’s future rests with the commitment of the board and the staff, and their ability to “make do. ” This interview with Pat Little, administrator, and Eula Hall, social worker, at the Mud Creek Health project in Craynor, Kentucky, focuses on the dilemma they face if they are to keep their clinic open. In recognition of her commitment and achievement, Eula Hall received a Presidential Citation from the American Public Health Association in 1975.

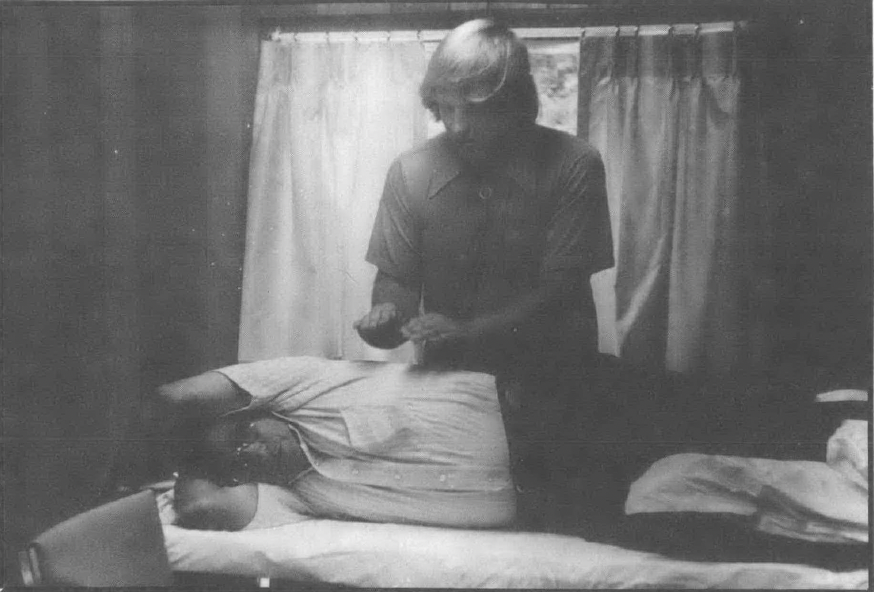

Pat: Our clinic tries to give people what they need. We not only have a doctor and a nurse, but we also have a therapy room for black lung and a social worker that can look after people, to give food stamps, to go to hearings to see that their rights are protected and taken care of. A lot of these other programs around here look at us and wonder how we keep surviving. To a certain extent, they’re not only surprised, but they’re sorry that we do. We’ve been breaking even; I don’t know how, but we have. But even with the pharmacy, we were only breaking even. We would see sixty and on up people a day. Our private paying patients, they pay what they can, you know, sometimes two or three dollars at a time.

Eula: About one-fourth of our private patients, which is about onefourth of our patients, don’t pay anything. It varies from month to month. Some months half of our private patients may not pay anything, it depends on the status of the patient and their income.

Pat: Like right now [during the wildcat strikes], there ain’t nobody working. Now that means because our doctor can’t be reimbursed by the Fund and other people have no income, the clinic is providing a lot of free care. I wish you could see the stack that we have; we have just been continuing providing care — for June and July. A doctor comes in twice a week on Tuesday and Thursday, there are thirty or forty chart sheets for UMW patients every week, but we couldn’t charge anything. They depend on the clinic and they need care. But we just can't keep operating like that.

Over the weekend I did our quarterly report and taxes, federal and Kentucky taxes and it nearly drove me crazy because 1 kept trying to figure out how can we stay open one more month. We’re just barely making it. Then 1 told Eula, “Eula, we’re just not going to be able to see the patients free-of-charge anymore. We’re just going to have to close. We can’t pay our staff.”

You never know what you’re going to get from Medicaid; you can’t depend upon them at all. We billed them $5,000 for March and we got $1,900 back; you don’t know what you’re going to get. They have little letters to tell you why they switched the pay, that the patient was ineligible at the time or the name was wrong or the numbers were wrong. And you know you can’t bill a state aid patient for the rest of what it costs you.

But where we have had bills for Medicaid of $ 1,300 to $ 1,400 a month, our bills for June were $480; now that’s just two days a week, but that’s it. Medicaid won’t reimburse physician’s assistants or nurse practitioners, they just reimburse the physician and we only have him two days a week since our regular doctor left.

Eula: We filled out a proposal for the Robert Wood Johnson foundation, but the doctors we had at that time didn’t want it. They didn’t want money from foundations or anything. We filled out everything but they wouldn’t fill out their part. So it fell through. They said they didn’t want to spend bureaucrats’ money, but I’d just as soon spend bureaucrats’ money as anybody’s. We can provide good health care with that money. There ain’t no better use for it.

Pat: We did have a grant from the government for black lung therapy. The grant was supposed to go until June, but they called in April and they said not to do it anymore because they ran out of money. The UMW Fund was billed for the respiratory patients that we were seeing separate from the retainer. The $5,000 from the Fund was just for office visits. The respiratory program is still needed, but we had to close it down. What really irks me is they set this up, you know, we had to borrow money to build that room on because we had to have a room for that before we could get the grant and then you have all this equipment and then, Kaboom! It’s gone and we have to lay off our respiratory therapist, and all that equipment back there is doing nothing. I just can’t understand some things the government does.

Eula: The University of Kentucky gave us a nurse and a community health educator one time. They gave us a social work student one time. I think they could help in a lot more ways. I think they could, instead of having all these interns all doing their thing down there at the University of Kentucky, they could put mobile units, or satellite clinics out here. I think they ought to go to where the people are; the people cannot go to them, not from here.

Pat: What we need out here is a physician who’s dedicated. We’ve been trying since last year to recruit a physician. Our first two doctors were paid $12,000 a year. Our third doctor was a sister, and we paid her $8,000; she gave it to her order, and you know, she said it really didn’t matter. We didn’t have to pay her a big salary. But after those three we had a big problem finding a doctor we could afford. A pediatrician came and visited with us and she really liked it here, but she wouldn’t come for less than $50,000 a year. So that’s the reason we went to the National Health Service Corps, because it would be difficult to pay out a big salary; but if things had continued with UMW we could have paid $30,000 or $35,000 for a doctor.

Our pharmacist is the highest paid professional; we paid him $15,000. That’s a hard decision to make, but any decision you make, you make it for the patients. Now we’d never give anyone $15,000 if it were left up to us. If we get a doctor back, then we’ll start looking for a pharmacist.

We applied to the National Health Service Corps directly but we got a letter back saying that we had been approved for a physician. I wrote and I called the day after and I told the guy that PA’s wouldn’t help us a bit because they weren’t recognized [for reimbursement] in Kentucky. Well, the man that we had been working with called me back a little bit later and he was pretty upset, I guess, because I had talked to somebody else and he said we were still on the list for physicians but we’d have to wait, and there aren’t any physicians available at this time, and besides, he said, “I don’t think you’ll ever get a physician because I’ve been out there and I’ve seen your place.” So you see, I really don’t think he’s helping us. But this doctor who says she’s coming, she’s been out here and she said she really liked it. She’s dedicated to her patients; she said that it was just what she was looking for.

I can remember when we first started. Have you ever been up to Tinker Fork? Well, it is kind of unbelievable. Using mayonnaise jars to hold tongue depressers and fruit jars for urine specimens. We had bake sales and rummage sales and things like that to raise $400 just to pay the rent. You know, if it hadn’t been for the UMWA cutback, we would have made it. Or we could have borrowed it to go on, but the way things are, you’re afraid to borrow to continue.

Eula: See, we’re going to be forced to be closed; we’re the only place that’s providing free health care. We don’t deny health care to nobody, regardless of their ability to pay; we see anybody who comes through that door, money or no money, and that’s the intent of the clinic, to give health care to people that need adequate health care. But, how much longer are we going to be able to stay open without some funds?

Pat: We’re paying our nurse and our receptionist and our lab technician full time, but they’re only working two days a week, the two days when the doctor comes in. If I cut them down to just two days a week, they can draw more on unemployment. But we have to have them just for that doctor; it’s going to kill us that way. It’s just not going to work. I don’t know what to do, I really don’t. We have charts on 5,000 patients. Many of our patients are doing without health care right now. They’re not going to other providers; they can’t afford it. Doctors have quit taking new patients.

If we had half the money of some of these other programs, we could continue to provide service. Me and Eula, we borrowed $5,000 to start our pharmacy, and I felt much better when we paid that off, you better believe it. But that was the only way we could do it, you know, because we never had that much money to get ahead. We haven’t been in the red, but we just barely make it month to month.

I think we’re getting the job done. We had a call from the state licensing board last Thursday, about our state inspection. She said, “I have been to all the big hospitals, clinics, but I’ve never been anywhere where I felt the job was being done like it is here.” It really made me feel good because just the week before the doctor said, “You all will never get licensed.” I don’t know why he said that. But I guess he had always worked in big hospitals. She said we were doing a better job than any other place that she had inspected. Yeah, that really makes me feel good. You know, that’s the state talking.

But you know the staff, we have always worked together because you never get anything if you don’t. It really gives you a good feeling, too, and like I told the state inspector, “I hope we’ll be here when you come back.”

Eula: I don’t think I could be happy working anywhere else. I like to organize. I like to work with the UMW and the tenants’ union and you can do a little bit of that and a little of other things, too. I really don’t know what else I Would do, I swear. Well, there are fourteen people out there right now that are waiting to see me about this and that and the other thing, you know. One needs a form for food stamps, anything they need in medicine or in anything else they need, they come to us. We’re a comprehensive health program. You better believe it.

Tags

Richard Couto

Richard Couto, Pat Sharkey, Paul Elwood, and Laura Green — all affiliated at the time with the Center for Health Services at Vanderbilt University — conducted an extensive evaluation of RCEC for the U.S. Department of Education in 1986. This article is adapted from that report. (1986)