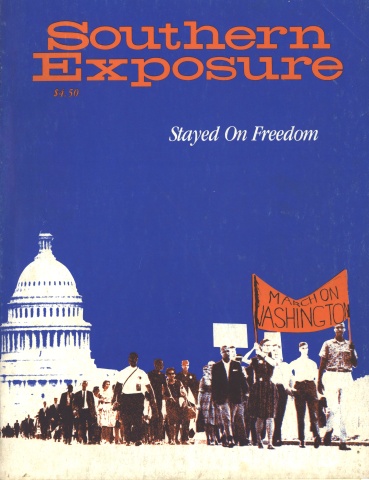

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

You could characterize Miami as the Los Angeles of the South: a city of mythical glamour and tacky tourism; a city that promotes itself while allowing its citizens, old or poor, to die of hunger within its boundaries; a “city of night.”

Liberty City, which borders Miami, is an unincorporated section of Dade County, Florida. Encompassing more than 500 square blocks, the neighborhood has the starkest poverty in Dade. It is a series of neighborhoods really, without any semblance of political power, plagued with rampant unemployment, decrepit housing and widespread drug abuse.

In Liberty City, site of the May, 1980, rebellion against living conditions and the police, there is hardly any person who can mention “police” without mentioning “brutality.” Police are everywhere: there’s a cop on the corner who beat up your brother, the cop in the quick-mart with his hand on his gun, and the cop who’s hammering down your door because he’s mistaken you for a dope dealer.

“These fellows are getting outrageous,” said James Ward, Sr., 62, a construction worker who was beaten by cops in Liberty City in 1979. “My head has been giving me trouble ever since.”

According to Dade County Public Service Department complaint figures released in January, 1980, approximately 200 cops at the core of the department exhibit a “strong pattern” of brutality. Of these, more than three dozen were assessed as mentally unstable and in need of psychiatric help. In the five years preceding the Miami uprising, an average of one charge of police brutality was filed every other day, a total of more than 930 charges!*

These reports represent only those victims who chose to complain, a mere tip of the iceberg. A typical victim would be a man like Reuben Mortimer. Mortimer, 40, was picked up by the police on a burglary charge; he was kicked and beaten so badly while handcuffed that he was forced to have his spleen removed. The laid-off factory worker later was shown to be innocent.

The majority of the victims had never been arrested before. Overwhelmingly, they were unarmed. They were not picked up for committing violent crimes and, in fact, most were stopped for traffic violations or for hanging out on a street corner. Significantly, nine out of 10 brutality victims were acquitted of all charges against them.

The battle against police brutality in Liberty City is an ongoing one. In 1970, charges of brutality were filed with the federal government by 17 black teenagers and five adults. The plaintiffs accused the Public Safety Director and 18 officers of following a “consistent pattern” of violence. About 200 residents of Liberty City — called “the combat zone” in police slang — formed a Committee of Concerned Citizens in 1973. This committee, which included over 100 taxi cab drivers, conducted several protests against police activities before its dissolution in 1976.

Only months before the police murder of Arthur McDuffie, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People publicly called upon the Justice Department to investigate instances of brutality in Miami. Not until the rebellion sparked by the acquittal of McDuffie’s killers, over a year later, did the federal government see fit to make such an investigation.

In a meeting of city residents held in the aftermath of the May uprising, one elderly white man summed up the feeling of many Miamians: “Too bad an investigation didn’t occur 10 years ago. There’s no need for investigations now. There’s a need for prosecutions.”

Arthur McDuffie, a sales manager for Coastal State Life Insurance Company, left the home of Carolyn Battle on December 17, 1979, to return to his sister’s house, where he lived. Almost immediately police stopped him, apparently for a traffic violation. He tried to outrun the police, and eight minutes later he was being beaten with flashlights and nightsticks by an estimated 10 to 20 cops. His frontal brain lobes were destroyed, and he lapsed into a coma. Four days later McDuffie died at Jackson Memorial Hospital.

While some cops dropped McDuffie off at the hospital, others demolished his motorcycle, trying to make it appear he had been in a routine accident. The initial police report stated that McDuffie killed himself while fleeing police.

Five Miami policemen eventually were brought to trial for the murder. The heaviest charge state prosecutor Janet Reno preferred against the five was manslaughter. Charges were also filed for tampering with evidence.

This was not the first time that these defendants were charged with the type of abuse that was exposed during the trial. The five had been named in 47 citizen complaints, 13 internal reviews and 55 use-of-force reports. Three of them are among those the department determined need psychiatric aid. Only one of them, William Hanlon (called “Mad Dog” by fellow officers), had ever been reprimanded by his department.

Despite evidence presented by the prosecution in the case (Dade County’s medical examiner testified that he was “aghast and horrified” by McDuffie’s condition), the all-white, six-man jury brought back a verdict of not guilty on all counts.

Within minutes, Liberty City was alerted. When the news was telephoned to a local Lum’s, according to state NAACP president Charles Cherry, “The reaction was immediate and loud, but somehow no one refused to believe it. Somehow, we all thought it could happen, that justice was not available for blacks, especially when they are up against white policemen.”

The local NAACP put out a call to the black community for a rally at the Dade County Justice Building at seven p.m. Seven thousand gathered there, and, while people in the crowd harmonized on old-time justice tunes, the police attacked.

“At about 8:50 p.m., the police deliberately raced two cars, with lights flashing, through the center of the crowd,” recalled state ACLU director Eleanor Ginzberg. “The mood of that crowd changed immediately. Ten minutes after that, a car was turned over and burned.”

The crowd smashed the plate glass door in the Justice Building, then tore the door off its hinges. Cars were overturned as people surged towards the Dade County Public Safety Building; SWAT squads responded with dogs and tear gas.

The rebellion against all that the acquittal represented lasted three nights and caused over $200 million worth of damage. Most of the damage was confined to Liberty City, where police drove the black protestors and National Guardsmen contained them at gunpoint. “The authorities are directly responsible for this happening,” Ginzberg commented. “The place was ready to go. This was a tragedy, built on racism that is part and parcel of that community.”

Walking through Liberty City on Tuesday after the uprising, it seemed as though an enormous wrecking ball had swung down from the clouds. On every major thoroughfare, jagged low walls indicated where businesses had existed. Smoke from still-smoldering buildings and armed National Guard troops at every turn gave an eerie air to the nearly empty streets.

During the heat of the uprising, newspaper stories included wild exaggerations and completely fabricated tales. For example, in a famous story entitled “To Strike At Anything White,” Newsweek reported that “Police found one man with his ear and his tongue cut off and a bullet wound in his abdomen. A red rose had been stuffed in his mouth.” In point of fact, the gentleman — sans rose — was beaten and mutilated by a crowd angered because he aimed his car at and ran over a black child playing in her front yard. The child was permanently crippled.

“The TV stations come in, turn their lights on and ask you what happened,” a James Scott housing project resident complained. “Then when you turn on the six o’clock news, all you see is burning and all you hear is how white people got hurt.”

After the fog enveloping the media cleared, it was apparent that, rather than a wholesale massacre of white passers-by, police and Klan types were responsible for most of the 14 deaths. For example, Allen Mills was shot in the back by the police before curfew while riding his bike. Lafontant Bienaime died from police bullets while driving his van. Nine blacks died, as did four whites and a Latino man.

An elderly black woman later commented sadly, “Well, in every revolution, some innocent people are killed.”

Jackson Memorial Hospital reported that, by Wednesday morning, they had treated 196 people for injuries. Police arrested about 600 blacks; they claim that nearly 4,000 law officers were unable to track down a car full of whites who patroled Liberty City for three days, shooting at black people and killing two, Thomas Reece and Eugene Brown.

The Justice Department’s Community Relations Service and nationally known black leaders collaborated to try and cool down the community. Their success was, to describe it moderately, limited.

Andrew Young was booed off the stage at Tacolcy Center by young people. The director of Tacolcy, Otis Pitts, said, “Blowing in and out of town is not what we need.”

Jesse Jackson, disdaining powwows with officials at first, strode into Liberty City and arranged a meeting with the press and about one dozen “spokesmen” for the community. Ralph McCartney, an old hand in Liberty City, laughingly commented, “Jesse Jackson went out on the street and picked up the winos.”

Among whites there is a remarkable amount of sentiment supportive of the rebellion. The Citizens Coalition for Racial Justice was formed, in the words of a member, because “Whites were frustrated and didn’t know what to do.” CCRJ members “nailed” federal officials in Miami, winning a promise that the federal government would investigate the McDuffie case. The whites and Latinos in the coalition endorsed the rebellion’s underlying intent and played a large role in publicly opposing the characterization of the disturbance as a “race riot.”

“Nearly four months after the violence, the effort to solve Liberty City’s problems remains embryonic. . . . Whether it will all come together, and how much good it will really do, won’t be known for years,” commented the Miami Herald in September, summing up the attempts to address the demands of the city’s black community. This assessment is a very sober one, based on an examination of the programs ostensibly designed to solve the black community’s problems.

During the uprising, numerous neighborhood groups presented de- mands to the city and press which included the creation of a civilian review board of police, with subpoena power; jobs; a revamping of the electoral and justice systems; political refugee status for Haitians; and much more.

After May, there was a flurry of activity on the parts of the government and private sector to “find out what these people want.” Again, Liberty City residents reiterated their demands at numerous public meetings. Proposals in response came as frequently as Miami rains.

A federal grand jury indicted one police officer: Charles Veverka, targeted by a Carter task force for violating Arthur McDuffie’s civil rights, was the sole officer willing to trade incriminating information against the other four killers for immunity from state prosecution. The task force then disappeared, buried with a statement by Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti. He declared that he would not organize a “witch hunt” to investigate police, and indicated that the federal government would back off from a thorough investigation.

In December, 1980, Veverka was tried — and acquitted — for violating McDuffie’s civil rights. The trial, first slated for Miami, was rescheduled for Atlanta, and finally moved to San Antonio, Texas. Denis Dean, Veverka’s co-counsel, applauded the final choice of San Antonio because blacks make up only eight to 10 percent of the population and because “I like the military aspect of the city.”

“The system is only going to help the system,” declared Frankie Askew, a self-described “ghetto mother” of eight who lives on the outskirts of Liberty City.

Mrs. Askew, a veteran community activist in fights for tenants’ rights and day care, is skeptical about government and private sector promises of relief for the black community: “I’m tired of hearing well-written speeches. I want to hear the truth from someone’s heart.”

Sitting in her plant- and flower-filled living room she gave an example. “The governor appointed a commission. The commission started having hearings. People appeared there and voiced their opinions. Then,” she concluded sarcastically, “the commission was disbanded.”

Although numerous plans and analyses, with accompanying rhetoric, have been discussed by government officials, the only concrete, constructive relief to Liberty City has been in the form of loans to businesses.

Dade County spent $450,000 clearing debris and razing shells of buildings burned down during the rebellion. Federal authorities approved $10.6 million in loans to the 123 white-owned businesses injured. County and city authorities agreed with the federal government that the Overtown neighborhood, a black community, is a “slum and blighted area” and therefore should be destroyed in order to make way for a shopping center. About $5 million in loans to begin minority businesses was allocated to the City of Miami by the White House. And finally, the Florida legislature created a Revitalization Board of 11 members without any power. The board plans to use “moral authority” to coordinate nonexistent relief.

Literally not one cent nor one ounce of organization from the government has been applied to the real, long-term needs of Liberty City residents.

Homer Brennan, living in the James Scott housing project in the heart of Liberty City, believes that government inactivity and half-measures create only “more frustration.”

He described a temporary jobs program for senior citizens that “isn’t any good as far as hardcore poor, elderly blacks here are concerned.” The under-minimum-wage payment for a four-hour work day is just enough to raise income-based rent in the project, but unfortunately not enough to pay the increase. “So why go through the paperwork?” he asked. He acknowledged that a few young people were given summer jobs by the county, but now are “having a hard time receiving their last paychecks.”

One of the demands that arose from many groups during the rebellion was for an all-civilian police review board with subpoena power. With a flourish of publicity, the city manager’s office created a completely powerless board that will “monitor complaints” about the police. The board, composed of only two civilians, plus a member of the Fraternal Order of Police, a representative of the police chiefs office and an assistant city manager, will be kept apprised of the work of the police internal security section. A civilian staff of four people will set up six offices in which they will be accessible to any organization that wishes to voice its opinions about the police. Board members and staff will all be hired or appointed by the city manager; final decisions on expressing opinions or communicating with citizens publicly will be made by the police chief and the city manager.

In July, the City Commission decided to increase the police force to 914 officers by September, 1981, with a short-term goal of 814. Recruiting, processing and training time will be cut from 51 weeks to 32 to 34 weeks.

The commission assured the public that the hiring would be consistent with the police force’s affirmative action program. The program, which arose from a Justice Department suit against discrimination in 1972, is eventually supposed to bring the City of Miami police force’s makeup into line with the city’s population makeup: about 25 percent black, 25 percent white and 50 percent Latino. In 1974, the total black and Latino representation on the force was 21.8 percent; currently, the total is 36 percent.

The beefing up of the police force is accompanied by a renewed license to kill that is an earmark of the Miami force. On June 13, 1980, Officer Gerald Schwartz killed Claudio Lima while off-duty, shooting him several times, allegedly in self-defense. Schwartz has been accused 13 times of abusing civilians, and the police department upheld the accusations five times. His only “punishment” has been a reassignment to administrative duties. A quick trip to the desk is standard City of Miami police procedure for police officers whose abuses in Liberty City are exposed.

As they did for a short time after the 1968 and ’70 rebellions here, the police “are relating to very young kids, going around and giving them candy, playing with them,” remarked Brennan. “But they still jump out of their cars with shotguns!”

The response of the private sector to the May disturbance can be summed up in two words: minority business.

The Greater Miami Chamber of Commerce and the Miami-Dade Chamber (with, respectively, mainly white and mainly black members) have started a program that advises minority loan applicants, refers them to potentially sympathetic banks and encourages Chamber members to buy minority goods and services.

In a sense, Liberty City has long been an independent entity. The section was built up during the 1920s by Alonso Kelly, a black realtor who convinced other blacks to move there for “liberty” from the overcrowded ghetto in west Miami, “colored town.”

“Liberty City was a place where I longed to live,” reminisced Bea Hines for the Miami Herald after the 1970 rebellion. “The apartments had yards with real grass and some even had flowers. . . . Everybody in Liberty City knew everybody else, if only by face. And a one-block walk down the sidewalk could really tire the tongue and jaws because nobody dared walk past a porch without a smile or greeting.”

While Bea Hines was growing up, five or six families lived on a block. Urban renewal and migration from the country into the only community in which blacks could acceptably live caused overcrowding. The borders stayed tightly shut; during the Korean War, the Ku Klux Klan bombed Carver’s Village because it was constructed “too close to whites.”

The population grew to 75 or 80 families per block. “Instead of grass, black asphalt parking lots went right up to the front door,” Hines recollected.

Finally, in the summer of 1968, Liberty City erupted for three days. Police killed three black men, and about $100,000 worth of damage was done to businesses.

The outcome of that rebellion is a by-now familiar story. Metropolitan Dade’s Department of Housing and Urban Development (Little HUD) promised to build decent streets and sidewalks within five years. Little HUD also planned to modernize 1,734 public housing units in the James Scott and Liberty Square housing projects, develop a park, build a family health facility and create a sewage system for both housing projects, using a $3 million federal grant.

Dade County chipped in, promising two swimming pools for Liberty City, and the Model Cities program allocated $9.6 million for relief.

The outcome, however, was that no parks, no pools, no decent health facility evolved. Housing unit modernization was slapped together and sank in a morass of red tape. At the time, John Bennet of the Tacolcy Center commented, “That $9.6 million, what’s that going to do? That’s not going to do anything but pay salaries. We’ve got a $150 million sewage problem out here.”

The programs aimed at eliminating unemployment were equally inadequate. The federally funded Concentrated Employment Program and the Chamber of Commerce offered a total of 1,561 jobs and training positions. In 1969, the unemployment rate in Liberty City was already an official eight percent, almost 3,000 people.

“There were very few changes for young people,” Mrs. Askew said, “but some good things came out of the ’68 rebellion. Before that time, young blacks, when they got out of high school, couldn’t find work to do. After that, they were finding places for them; the government was sending money down. Probably if it hadn’t been that way, they might still be walking the streets.” She added, “Some still are.”

“For two summers, I had to go raise holy hell to get my child a job,” she smiled. “I had to make sure they did not give him a runaround. If they’re going to give anyone a runaround, let it be his mama, because his mama isn’t going to stand for it.” The many who did not benefit from the scanty jobs programs in 1968 and 1969 are remembered poignantly by Mrs. Askew; her son’s best friend of those years, who did not receive a job, was involved recently in a street-killing incident.

The Metropolitan Transit Authority conceded a bus line from Liberty City to Miami Beach in 1969 for service workers, and promised to “study” the question of bus lines to Hialeah, where factories that would hire blacks were located.

In 1967, the Florida legislature told the state welfare department that it must write its welfare checks in 1968 from a small, set fund. As a result, in June of 1968, nearly 25,000 people in Dade County qualified for welfare, but only 65 percent of their basic needs could be covered by their checks. By June of 1969, almost 5,000 people had been added to the rolls, and their checks covered only an average 60 percent of needs.

After the ’68 uprising, Police Chief Walter Headley died. He had been criticized in a federal report after the rebellion as having “carried virtually unchanged into the late 1960s policies of dealing with minority groups which had been applied in Miami in the 1930s.” Bernard Garmire, who instituted a community relations program for the force, succeeded him. The program, a candy-for-kids concept, soon withered away. Meanwhile, police in the Central Zone’s Liberty City retained carte blanche brutality privileges.

The drive into Liberty City’s housing project is an excursion behind Miami’s glittering facade of tourist brochures. This neighborhood is not so much a residential section as it is a warehouse for storing cheap labor to be employed by the low-wage hotels and restaurants that form the backbone of Miami’s tourist industry. Like any other tourist trap, Miami is without the diversification in its economy that allows for the stable development of various types of industry. The tourist industry grows like a weed that chokes off almost everything else.

Homer Brennan, who is a member of the Scott Family, a community-based organization formed after the May uprising, declared, “The conditions in this project are terrible. The electrical system is a fire hazard; the gas lines around here leak; the plumbing is awful. Some days you go out and the sewage has completely backed up and it will sit there until the sun dries it out. Do you realize the bacteria? The windows have no screens or are broken; it hasn’t been painted in years; whenever it rains, the telephones go out. There are no pay phones around here, plus try to get a repair man!”

Brennan feels that money should be given to Scott Project to hire someone to lead sports programs for the youth. He believes that young people care about the conditions in the community: “They say, ‘We care. We don’t mind going to the Tenants’ Council meeting. But nothing ever happens.’ It’s just like when you vote for a representative. They come with promises, win [the election] and then cut the CETA money.” The young father decided to run for a seat on the Tenants’ Council because current members are not “downtown banging on doors every day and organizing Scott Project into a voting bloc.”

Only one in 15 youths in this project has a job, Brennan estimates. The official statistics are telling: 501 families are on welfare out of a total of 762 families in the project. The average income for a project family is $4,500; more than half do not even have an income of $4,000. The family structure of the average Scott household consists of a mother trying to make ends meet for several children on welfare and food stamps that cover about half of their basic needs.

Scott Project was the scene of Miami’s second 1980 rebellion. In July, two of the most pressing problems of Miami’s black community — jobs and police brutality — came together to catalyze the uprising.

On the morning of July 15, more than 600 teenagers appeared at a job fair sponsored by CETA. They were angered to find only 200 jobs available, most calling for skills that few of the youths possessed.

Later that day, police attempted to arrest several teenagers who, police allege, were involved in a robbery attempt. The mother of one of the youths was treated shabbily by the officers, and then officers beat another teenager in front of about two dozen onlookers. The crowd first reacted by taunting the police, and eventually drove them off with rocks and gunfire that wounded one officer. Police reinforcements also were driven off by a crowd that had grown to number several hundred people. By midnight, four more police were wounded by gunfire and another injured by a metal pipe thrown through a patrol car window.

Government officials, the police department and certain elements in the black community worked furiously to portray this so-called “mini-riot” as the apolitical doings of a handful of “hooligans.”

Marvin Dunn, a black university professor, labeled the rebellion a “carnival” and claimed that blacks had “lost the moral edge” through it. Robert Dempsey, acting director for the Dade County Public Safety Department, said, “Right now, the area is under the control of the criminal element, people with guns.”

“What we have now is a bunch of hooligans. We don’t want a racial incident,” remarked Henry Witherspoon of the same department.

Governor Bob Graham called the rebellion “the problem of well-organized and well-armed hoodlums attempting, by use of guerrilla tactics, to take over the housing area.”

President Jimmy Carter, speaking in Jacksonville, Florida, on the second night of the mini-rebellion, piously placed blame for the rebellions on the leadership in the black community, Cuban refugees and the local government, and adeptly sidestepped the effects of four years of his economic and social policies on Miami.

In the midst of all this, the Dade Police Benevolent Society called for a removal of the “restraints” that had been imposed on the police since May. Shortly afterwards, the Congress of Racial Equality and “Cops for Christ” joined in the negative characterization of the rebellion by counter-demonstrating in Liberty City, while the Civil Rights Commission suggested that the staff and resources of the Justice Department’s Community Relations Service be expanded to prevent “riots.”

Homer Brennan and Frankie Askew are concerned about the future of Liberty City, but take a different view from public officials and black “leaders.”

“You see a lot of happiness in this community, a lot of pretty kids flocking around,” Brennan stressed. “There are no YMCAs for them, no Boys’ Clubs, nothing to keep the kids from getting involved in the nasty little things that adults do to survive.”

Mrs. Askew declared, “One of the reasons that attitudes have not yet changed here is that the rebellion was based on the criminal justice system, and that’s still the same thing. It’s a shame to say I’ve got three grown sons and every one of them left here to find a future. Don’t you think I want one of my sons here with me? But there’s no future here.”

She believes that “Young people need to be heard, and they don’t really have anyone who wants to listen to them. The government says, ‘We’re just going to dish this out to quiet you down,’ and young people are saying, ‘You’ve been our voice for so long. We want our own voices.’”

* Local reporters compiled these figures only after a court order opened previously secret department files to the public eye.

Tags

Jehu Eaves

Jehu Eaves has been active in the black liberation movement since his high school years. He served as a staff member for the February 2, 1980, March in Greensboro and worked for The Southern Struggle, the newspaper of the Southern Conference Educational Fund. (1981)

Chris Lutz

Chris Lutz has been a SCEF staff member since 1978, and is currently editor of The Southern Struggle. (1981)