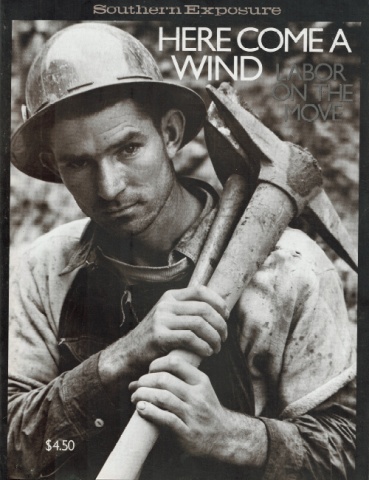

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

Jones Avenue in Andrews, South Carolina, is as unpretentious as its name implies. On the sandy soil along the blacktop strip are settled the homes and gardens of black families — not so long off the farm or piney forest — who came to Andrews looking for steady pay. Employment in this coastal plain town of 3,000 usually means Oneita Knitting Mills, a “runaway shop” from Utica, New York, which moved to Andrews in the early 1950s.

Owned by the Devereaux family of New York City, Oneita Mills was locally supervised by plant manager Frank Urtz and a company director, Andrews banker A. H. Parsons. Their large, brick homes were a far cry from the houses on Jones Avenue. In fact, Frank Urtz didn’t even live in Andrews. He commuted the 20 miles from the larger coastal city, Georgetown. Mean¬ while Oneita's payroll helped Andrews grow, and Parson’s white-columned bank regularly made home, car and furniture loans to the Oneita pieceworkers.

Before the early 1960s, those workers were all white — except for two black janitors. They enjoyed the relative protection of a union contract which the International Ladies Garment Workers had maintained since it followed the underwear company south from Utica. But in 1963, all that began to change. In that year, the company decided to break the union.

Herbert White, one of the two black janitors, went out on strike with the other ILG members in a vain attempt to win a new contract. Plant Manager Frank Urtz had told White that he couldn’t join the union because his face was black. But White joined anyway. After six tong, bitter months, he and most of the other workers went back into the plant without a contract and without a union.

After the strike, several ILG leaders received office jobs from Oneita; the former president of the local became the personnel manager. Needless to say, many workers were disillusioned about unions. But not Richard Cook. He was fired for his union activities, petitioned the National Labor Relations Board, and several years later received his back pay and his former job. Cook, Herbert White, Dorothy Glisson, Effie Shurling, Rena Fdy and a few others remained firmly committed to unionization, but they had to wait. They knew that Urtz relied on ”pets and spies” to maintain control and spread suspicion through the plant.

Then, in 1964, the Civil Rights Act forced Oneita to hire black workers. Although Andrews had not experienced an active civil rights movement, black people watched the events in Montgomery, Selma, Birmingham and across the South on television. They took pride in their blackness and in their leaders. When jobs opened up at Oneita, they gladly moved in. Some black women had previously driven the thirty miles to the resort of Myrtle Beach to do maid service and waitressing for the summer tourist trade. Others had tried to keep small farms going or sharecropped land while their husbands sought work in the steel mills of Georgetown, the nearby paper pulp mills, or the naval yards 50 miles away in Charleston. The necessity of a steady income brought many of these women into the single story, aluminum-sided sheds of Oneita Mills. At the same time, the South’s expanding economy lured away the white, semi-skilled workers with better-paying jobs in other shops.

By 1971, Oneita had opened a second, smaller plant 20 miles away in Lane, and its total workforce of 920 had shifted to 75 percent black and 85 percent women. The Textile Workers Union of America began to view Oneita as an ideal place to organize. The racial mix was a clear plus; and the company was a relatively small, family business that could not shift its production or hold-out with the limitless power of a diversified giant like J.P. Stevens. Furthermore, a base in Andrews would be strategically important for organizing the 20,000 textile workers within a 30 mile radius of the town.

In June, 1971, TWUA sent in its first organizer, Philip Pope, who immediately went looking for his friend Pete Pope (no relation). Instead he found Pete’s mother, Laura Ann, and his brother Jesse. Frank Urtz had tried hard to make Jesse Pope one of his “pets ” but Jesse knew which side he was on. With his mother and old-timers like Richard Cook and Herbert White, he began signing up people.

On November 19, 1971, the union won the election for bargaining rights. The workers laughed the day before the election when Frank Urtz made a half-hour speech to his “family’’ telling them how good he’d been to them. That Thanksgiving week, they got their first company turkey.

Negotiations began in February, 1972, but the company offered an impossible bargaining posture known as Blakeney’s Formula (named for J.P. Steven’s anti-union counsel, Whiteford Blakeney). In effect, Oneita refused to discuss provisions for dues check-off or arbitration of grievances. On January 15, 1973, nearly ten years after the ill-fated ILG strike of 1963, Oneita workers walked off their jobs in protest against the company’s bad-faith bargaining. Six months later, the NLRB ruled that Oneita's management, particularly Frank Urtz, had written anti-union letters and in other ways engaged in unfair labor practices. It was a major victory: the ruling preserved the striking workers’ jobs from encroachment by scabs once a settlement was reached.

But strikes are won on the picket line and only sustained at the bargaining table. The workers held fast, black and white together, and carried their struggle into the community and into a national boycott of Oneita underwear. Finally, in July, 1973, the company agreed to recognize the TWUA and negotiate a contract with grievance procedures, pension and seniority rights, and dues check-off.

It had been a costly strike, for the union and the community. Women stood on the picket tine and yelled “scab” while their sisters went to work. Neighbors no longer talked as one replaced the other in the mill. But the battle also united the strikers and established a firm base for building the union.

The intensity of this experience still glowed on people’s faces when we visited Jones Avenue in the fall of 1973. The wounds of a community divided, the ugliness of the company, the enthusiasm for the union, the excitement of becoming friends with blacks or whites for the first time, the sweetness of victory, the lessons of united action — all were fresh in the minds of those we interviewed. The commitment was still there when Carolyn Ashbaugh returned in 1975.

In the edited interviews below, the strikers and their representatives share what the conflict meant to them, why they went out, how they worked together, and what they won.

Carmela McCutchen: What was it like in there? I’ll tell you, working conditions at Oneita were like the nineteenth century. There was no seniority, no protection at all from lay-offs, no pensions, no safety protection, no medical benefits. If you got a needle in your finger, they’d tell you to go back to work.

Rena Edy: They would come around to see if you was doing anything. And if something didn’t look right, he’d just tell you off. This boss man hated us. He said we was his family, but he wanted to work us to death.

Carolyn Jernigan: Whenever you’d go into that place, it was rush, rush, rush until you get out of there. Sometimes I get so nervous and tensed up that when I get out of there, I’m just not worth a cuss to live with when I get home. You’d be so tired and irritable, especially on hot days when there is no air conditioning.

Flossie Gibson: They’d give you little green pills to take two times a day because too many people have nerve troubles. That’s right, nerve pills!

Laura Ann Pope: There was no seniority. Nothing! If Urtz (the plant manager) decided he don’t like you and you don’t do what he say — I’m not speaking about the job, I’m speaking about his dirty work — he will bust you down and hire somebody out of the street. He wanted stool pigeons, he wanted Peeping Toms. It didn’t matter if it was false or true, just you bring the report to him.

That’s why he hated me. Cause I was real cool. My children told me how they operated, and when I went in there, I went standing on my two legs. When somebody say, “I’m going to tell Mr. Urtz,” I said, “I was hired here to knit, and I’m knitting, and I’m not takin no junk.’’ The supervisor run back and tell him. Then Urtz called me in the office.

He said, “Mrs. Pope, I want to know. Do you realize who’s plant manager down here?” I said, “Yes, I think so. I was told that you were plant manager.” He said, “I want you to know that I operate this plant.” I said, “Well, I understood that before I came in here to work. That’s the reason why when they bring me the order what kind of cloth you want to fill your orders, that’s why I fill them.” I said, “Now why are you asking me these questions?” I said, “Well, it seems as if you want to take over, as if you want to be the boss.” I said, “Oh no, I don’t want to be the boss of anybody but myself, and I’m going to do that.” I said, “Now you tell me what to do concerning your job, and I’ll do it. But I didn’t come down here for no other purpose. I have no intention of carrying out any other but knitting your clothes. And when my eight hours end, I’m going to punch my clock and go home.”

So he said, “Well, let me —” and they had already warned me about his finger pointing. And when he started one of these numbers across that desk, I said, “Wait a minute; hold it, Mr. Urtz.” And I picked up my bag from beside me, and I took my pad and my pencil out and laid them on my lap. “Okay, Mr. Urtz, you begin. You talk real slow, cause this conversation you’re having with me, we might hold it again in Georgetown in the courthouse.” He said, “Mrs. Pope, Mrs. Pope, you go back to your knitting machine in your department and you do your job.” I said, “Let me tell you something; that’s, just what I was doing when you sent for me.” And from that day he couldn’t stand my image....

...Well, Philip Pope, he was the first organizer. And in June, 1971, he came; I was on graveyard shift, so I was asleep. He knocked on the door, and finally he woke me up. He wanted my son Pete. They worked together at Georgetown Steel. He said, “I’ll tell you what I’m trying to do. I’m a home boy around here. I have a job with the International. I have a letter here to organize the Oneita Knitting Mills.” I said, “Yippee. I work there.” He says, “What!” “That’s right,” I said, “I was hoping somebody would come along to help straighten this joint out. You don’t know how happy I am.” So he said, “Let me go to the car.” And he went to the car and brought back a stack of blue cards. He said, “I know if if you are Peter’s mother, you’re going to work, you’re going to help me.”

I didn’t sleep any more that day. About 10:30 I started getting dressed to go to work. Started signing those blue cards. My son came home; he got in his car; Philip and I got in mine. We begin knocking on doors. We took Jones Avenue first. Then we stretch out all over town. Then we went on for days. Jesse was working in the mill and getting cards signed, and that’s how I began.

I was getting so many cards signed that they had an idea I was doing it on the job, which I was. I’d call the employees the night before and say I’m going by you to check on your machine and say a few words to you. And I’m going to put a blue card in your pocket or your hand or somewhere. It’s going to be in a piece of paper towel. Then I’m going to the restroom and when I come back through, you have it signed and in your pocket or in your hand. And I’d go through, “Hi, fella, how’s your machine working today?” with my hands in my pocket. I’d say, “Boy, you better go ahead and try to make production,” and I’d put that card in his hand so quick it would make your head swim; go on into the bathroom. And I’d maybe drop off twenty cards on my way going and pick up twenty coming back. And I would eat my lunch before break. While I was working I’d eat my lunch. I could sign blue cards in the mill on break time, so when break time came, I knew that was my time....

...After we won the election, they played this trick on me. The company controls the speed of the machines. They took my set of machines from me and gave it to a trainee and thought they would run me off. He couldn’t just fire me, because I had a contract to use on him and he knew it, so I stayed in the mill. He knew I could do it (take him before the NLRB). So he took my machine away from me, put me back in training, thought this would belittle me.

One night, I went to work. The mechanic told me, “I’m sorry, you’ve got to run the swing-top.” I said, “I’m sorry, I’m not going to run it.” I went and sat on a stool and said, “Good, I’ll sit here until seven o’clock in the morning.” So I sat there about 30 minutes, and then the supervisor came through. He says, “Laura Ann, what you doing sitting on that stool? Don’t you have anything to do?” “That’s the way it looks. Sitting down, making easy money.” He said, “Why you don’t go run your set of machine?” I said, “My set of machine was given to another girl.’’ When he sent me back, I checked the cloth, turned it on, started working'. I cleaned off everything. Then I got out my pad and went by each machine and counted every end. I went and set on the stool and added them up. Each machine is supposed to have 144 ends to make production. And he’s given me 102 ends.

Supervisor checked things out for me; before I left, he said, “You won’t have any trouble tomorrow night.” The next night he treated me like pie.

And everybody started clamming up, those pets, those pimps, those supervisors. They started watching me when I go to the bathroom. They wanted to get something on me. They didn’t want me to stay too long; they didn’t want me to hold a conversation with other employees as I passed, and I would do it every time.

Rena Edy: They put me wherever they wanted me to work; they wouldn’t give me enough machines to make production. And I told them I’d have to quit. He says, “How would you like a job walking around and inspecting the cloth on the machines, the needles?” I said, “Okay, I’d agree to that.” So when we walked out on strike, I think he thought I would stay in. But l didn’t; I came out.

Scott Hoyman, Southern regional director, TWUA: When you go up against a company this size, a relatively small family-owned company, one of the hard things is that personalities become very important. Frank Urtz, the plant manager, and Bill Smith, their lawyer, are the two people whom I would charge with responsibility for such a long strike. I think they led the top people in the company to believe that, first, the people wouldn’t come out. And secondly, when the people did come out, that they wouldn’t stay out. And if either of those things had been true, the company’s strategy would have been correct. But they were wrong.

Urtz was a smart man and some of his tactics in the campaign were not stupid. He used these things that we may think are silly, like the analogy of the family, “this was all family.” Well, that happens to be a pretty doggone effective tactic. And the strikers wouldn’t admit to being members of the family, but it worked for an awful lot of people for quite a long while. You know, Southern whites transfer family concepts to owners and managers. There’s a code of personal relationships and responsibilities, in the old style textile communities, between a worker and a man that lives in the white house on the hill and runs the plant. And so, the family analogy is sort of an attempt to project that image. “The father may spank you, but he will also feed you.”

Then another negative was this guy Bill Smith that Oneita used as their lawyer. Smith is an old adversary of mine. I spent off and on four years dealing with him for another plant. He has his own peculiar characteristics. You know, whether you like it or not, bargaining between a company and a union is exactly like diplomacy. It has all the suspicions, attitudes, vehicles and devices as relations between two countries. Usually, you have informal channels. But one of the frustrating things was that Oneita purposely did not present us with any informal channels. Bill Smith wanted all the threads going through his fingers. We tried to talk to this banker Mr. Parsons, who was on the board of directors of Oneita. He was also the Democratic county chairman, and we were interested whether that would help. But it didn’t.

Smith would only offer us what I would call a highly restrictive contract. He imitates the Blakeney formula (see introduction), which in essence insisted on a contract proposal which is very unsatisfactory to us, and the union is left with three choices. We have the choice of refusing the proposal and striking. We have the choice of accepting the proposal after long negotiations and finding ourselves unable to make the union work to furnish satisfaction to the members. Then, third, we have the choice of a stalemate, to continue bargaining. And that could go on for years.

So we had a big decision to make. We counted noses and made the estimates and talked to the negotiating committee about what they thought we could do. We had an excellent committee. They were tough, whites and blacks. So that was how we made the decision to strike.

We ran the strike in terms of union structure with a negotiating committee that was fairly large. I guess it had ten or twelve people because we were representing two plants. Then we had picket captains. They were very, very important people. You know, the Bible talks about people who were leaders of tens and those who were leaders of a hundred and then leaders of a thousand and so on. Well, our picket captains were leaders, basically, of twenty and they had a book and they would take attendance and it was a very important activity. We had that in both locations (Andrews and Lane). It turned out to be a good structure. And we had a commissary.

Financial liability would be considerable. I would think we paid out between $300,000 and $400,000 from the international union treasury. This is only in terms of direct financial assistance. I’m not talking about staff salaries, I’m not talking about time; this was a major effort by the Textile Workers Union.

Ted Benton, TWUA strike coordinator, now retired: Just before the strike started, another representative and I went down to the local sheriff and introduced ourselves and we told him we wanted to conduct a peaceful strike here. We noticed on the first morning we were overwhelmed with police. There were over 20 cars there. That many was here for 2-3 weeks, and then they reduced them some. On the first morning, I was trying to keep them from escorting the people in; they wanted to drive in 10 or 15 cars at one time. I instructed our pickets to walk between the cars. They had a right to go in, but they didn’t have a right to escort them in such a manner as they was doing. And the sheriff threatened to lock me up. And I said if he was going to lock me up for carrying on legal picketing such as we were doing, then he’d just have to lock me up. He turned and walked away then, and he didn’t lock me up. But during the strike, they did escort people in.

We never got hit with an injunction, which is one of the most surprising things to me. Usually they hit you the first few days to limit your pickets and destroy their effectiveness. I do feel that if it hadn’t been for this sheriff, that injunction would have hit us and the company tried every way they could to get an injunction. Of course, he read the riot act on us and told us he could bring it down on us any time he wanted to, only if there was not too much violence out there, he would not have an injunction.

That surprised me very much too. We had a little hassle out on the picket line; about two or three of our fellows got into it. And he called me and told me to bring them up to the headquarters, and I did. And he said he had three warrants laying there on his desk for their arrests,but he wasn’t going to serve them, and he didn’t serve those warrants. He used that to tell us — well, the fact of the matter, to use his exact language, he says, “I’m the toughest man in South Carolina.’’

We was overpowered with policemen all the time. We knew that he could get the National Guard at any time. He could drive us away from the gates which would break down our people’s morale.

Carolyn Jemigan: The one thing that made the strike a success was that you gotta pull together. One or two people can’t do it. That’s one thing that I’ve found out. Especially in some¬ thing like this. Frank Urtz told me himself that we didn’t have enough guts to walk out of that mill and go out on strike. But we did and we made a win. It don’t make no difference what color you is — black or white — you gotta stick together. You find out one thing, that you got a lot of friends outside, and a lot of people who will stick together. One of our songs says, “United we stand, divided we fall.”

Joyce Lambert: My daughter Tammy had gone to school with black kids and white kids: she had learned that color didn’t mean anything. Both of the children really learned it during the strike. More than one time I made the remark in their presence that I would rather know any of those black people out there on that strike was a friend of mine than any five of those white scabs that went along with me all the way to the walking-out point and then they turned their back on me. They learned to work with black people, that was one thing. They agreed to walk the picket line with me and they walked the picket line many a day. When we’d go down to the headquarters, the black and white children would play together; the food was all served in one kitchen. We was just like one big happy family.

Clyde Bush, TWUA organizer: The black and white unity in this strike was very important. You can’t take anything for granted anymore. Back a few years ago whenever you went into one plant the first thing that you looked to was how many blacks are there working in here. And if there were 40 blacks you could count on 40 votes. That was back in the late 1960s. Today, you can’t count on that. Management some way has got to them, and one of the ways management is getting to the blacks, they’re going in and hiring the best-liked, the best black they have in the plant and they’re making a damned supervisor out of him, and he’s the one carrying the load. To give you a good example of that in the Oneita strike, in the plant down in Lane, South Carolina, when the strike started there was 231 workers at that plant. Very few of them was white; the rest of them was black; believe me, they scabbed us to death. At the end of that strike we had 73 strikers; they had 261 workers in the plant, which 90 percent of them was black. So we had to work very hard on the picket line.

We would tell workers as they would scab into the plant what management thought of them. The blacks on the picket line would say, “Remember the good old days when you had to walk into the back of the restaurant? You wasn’t a human being, couldn’t come in the front door. Remember the days when you went in and asked for mayonnaise on your hamburger and the restaurant operator put mustard on it and told you to take it? Like it or leave it? Remember the day the plant manager Urtz wouldn’t speak to you because you face was black?” By using these tactics on the picket line, we were able steal the tactics from management and they couldn’t come back and use them.

Carolyn Jernigan: A lot of people were out there on extra picket duty just because they felt the need to be there. We would walk from 6:00 some¬ times until 6:00. That’s steady walking on those hot, hot days. When one of those scabs would stick their head out for a breath of air we would laugh and cut up and just eat them up. When they’d go through the gate, we’d call them a scab and all that. That’s what caused a lot of them to come out; they just couldn’t take that.

There was a boy who used to help us out on the farm. We tried to talk to him when he said he was going in to work. But he said that he was going in. He was only 16 — and you’re not supposed to go into work that young — but he went in and made two days. Then he came out. And I said, ‘‘Julius, why’d you come out.” He said that Frank Urtz had told him to sweep that floor and he said, ‘‘I’m not going to do it,” so he throwed the broom down and he come out.

Ted Benton, strike coordinator: We had them where it hurts. It’s not a J.P. Stevens or a Burlington. We had the bleachery strong, and we had the knitting department strong. They couldn’t operate without them. When the strike first started we had about 70 percent of the people out. They had a number of scabs in there, but they couldn’t get out any production. It was more a liability to them than an asset. They couldn’t keep up the quality. We had the skilled workers with us. The ones they had in the plant were mostly flunkies.

We’d hear about all the seconds that were going out, and we’d be out there on the gate and those trucks would come in loaded with rejects from J.C. Penney’s. Buyers were saying, ‘‘If you can’t send me good stuff, don’t send me anything at all.” That really hurt them. The boycott helped, too, but you see, it was the pickets that kept them from getting and keeping skilled workers. A lot of our people thought the boycott was the most important thing, but it’s very hard to carry on a boycott when you don’t have a brand name. They made stuff for K-Mart, but they put a K-Mart label on it. You’d go in a K-Mart store and you couldn’t tell what was made by Oneita. I think the strike was won on the picket line, as are most strikes. I kept telling the people, “We have all these forces at work for you, but the strike is going to be won right here on the picket line.”

Scott Hoyman, regional director: The boycott was another major decision which was made by the International union. Sol Stetin had only been in office since January, 1972, but he adopted a very aggressive policy in pursuing this target. The International union put more energy into this boycott and strike, I think, than any other activity since the Henderson, N.C. strike of 1958 to ’60.

It involved a number of very hard decisions. You always have to have priorities and make choices, and this strike was a priority. We postponed other things so they wouldn’t get in the way. Another important decision — and this had to do with the character of your representative on the scene — was the style of the strike. We ran it as a very peaceful strike, although there were some complaints about that. We had black union people coming from Charleston and from Georgetown who said that this ain’t the way to run the railroad. And we had a couple of confrontations over this.

One of which, at a mass meeting, I made the offer that if the folks wanted to vote for some other union to take over the strike and the other union would pick up the bill and furnish responsible direction to the strike, the Textile Workers Union would respect that decision. And nobody jumped up and so I guess that we retained direction of the strike, and we also kept paying the bills. But that issue, that challenge, or however you want to phrase it, that question which arose as to who should determine this kind of strategy and make these kinds of decisions was over that precise question: were we going to try to preserve a very peaceful atmosphere? And we felt that we didn’t have any choices. I’ll tell you one effect that it had. It really confronted the company with an unusual problem. You know, usually the company keeps talking about the violence and the disorder and the dynamiting and the homes being shot into, and judges respond to that. But even the sheriff said that there wasn’t any base for talking like that.

So despite some complaints, mostly from people far away, that style turned out very well for us. We were also concerned about whether the company would be able to get significant black leadership in the community to take a stand against the strike, or encourage people to scab. The black community pretty well stayed on our side. But in the white community, it was harder — and still is.

Joyce Lambert: I know one girl who was out with us, she was strong union. She was a picket captain and she was strong union. And her sister, who lived in the same house with her; she went in there and worked every day and ate our union groceries. The thing that got me most was some of these people had tried and tried and tried to get a job at Oneita. They had put in one application right in behind another. They wouldn’t hire them until we went out on strike and then they start calling in everybody.

Now my husband, he won’t let me ride a scab to work. My neighbor right next door worked in the knitting department. Well, I don’t hold a grudge. But he said, if she was able to find a ride while I was on strike, she can find her a ride while you’re working. She’s never asked me to ride again, and I’m glad. I really don’t know what I would tell her. I’ve had some of the women who crossed the picket line to ask me for a ride, and I’ve just said, “No, I can’t have riders!” So I think really way down deep they know why I said that. The church I went to, there was only two scabs in it. The rest of those were on the picket line.

But another girl that was out with us, she was secretary of the Sunday School at the Pentacostal Holiness Church, and they gave her a hard time. Because somewhere in the Bible it says — I believe in Romans — it says something about “to strike” and we looked it up in the dictionary, and it means to strike with your hands, to hit back. Some of these people, they think it’s sin to strike; they tried to have her thrown out of the Pentecostal Holiness church. She really went through holy terror. She had a hard time but she said she prayed her way out of it.

In July, 1973, the Oneita workers won a contract giving them arbitration, a good grievance procedure, a pension, dues check-off and job bidding. They had a contract to defend them from arbitrary power.

In the year and a half following the strike, the union won 41 out of 43 grievances filed; the strike convinced the Oneita Knitting Company to deal with its employees with more respect. By the end of the strike, the company had brought in someone over Frank Urtz. in March, 1975, he was removed completely.

Dorothy Glisson: What affected me really, before we had a contract we didn’t have the job bidding. If they wanted to give a good job or an easy job to someone, they would usually pick who they wanted. Their special ones. So after the contract — I’ve been here going on 23 years — I got to bid for a job in the mill. About six of us bid for this job which would take me off the sewing machine, off production, which I’d been on for 22 years; And it was doing rework; it wasn’t all that much better, but it seemed like it was somewhat easier. Took the strain off me, wasn’t quite as harassed. So I bid for the job. But they still, I think, had a little prejudice, because out of the ones that bid it they give it to another lady that didn’t have as much seniority as I had. That kind of got me hot, because I figured that’s what I wanted a union for, so I filed a grievance about that, on the basis of seniority.

When they checked on the six that had bid for the job, they classed us. They had a merit system giving us points. This other woman was number one, and I was number two, and the other one that was in the corner was number three. We was in there with Mr. Martin; I said, “I want to ask you a question. Why if I’m number two on the paper, why is number three over there in the corner doing the job?” He said, “I don’t know, but I’ll see.” So in just a few days they posted the job again, and I bid it, and I got it.

That’s the main thing; the people that’s running the mill can’t run it just exactly as they please. The union bargains, and we have something to help us out. If it wasn’t for that, I’d never have gotten the job. We have grievances, we have seniority, we have job bidding. We have many other things in the contract, but those are the three that really affected me, and if it hadn’t been for that I know I wouldn’t have gotten the job.

Charlene June: We had one that really stirred up something. We had nine girls who filed a grievance on a quality control job. They had the job up for bid; nine girls bid on the job, and the girl with the lowest seniority and who was a scab got the job.

The eight girls got together and they filed a grievance. They went through all of the steps and they didn’t get any satisfaction. The company said that they went by “adaptability,” “suitability” — anything unreasonable, that’s what they went by. “How the lady’s legs looked?” They didn’t say that, but that’s what it meant. “Adapability,” “suitability” — how she wears her hair and all that. Finally they took it to arbitration. To me, this was an important one; they took it to arbitration and we won. It was a union person that got the job. She got all of her back pay dating back to the day that they put the scab on her job.

Effie Shurling: I started working at Oneita September 12, 1962, as an inspector. I just want to be there four more years, and I can retire, with a pension, which I didn’t have before the strike.

George Justice, Local TWUA representative: We solve a lot of complaints for non-members. If they’ve had a problem, we took it up. The mechanics came over as a group and asked for a meeting with me. None of them belonged to the union. They came out and said, “We don’t feel the company is paying us right; we’re entitled to more money. If the union can do anything, we’re all going to join.” We met with the company and some of them soon got over 50 cents an hour increase. They all went to top pay and now they wouldn’t even talk to us about joining the union. Some of these guys are asking over $5 an hour. Yet they want the sewing machine operators and the people that are on lower rates to foot the bill for them. With dues at $1.75 a week, the wage increase that they have gotten this year for just one hour would pay their dues. And they work forty hours all the time....

We’re not getting very far with the older people who’ve been there 20 years and who didn’t come out on strike. Day before yesterday James Johnson, the president of the local, signed up a woman that scabbed during the strike and would never even talk to us about joining the union. We pick up one or two like that a month. And, you know, the ones we’ve picked up surprisingly have become active in signing up other people, more active than many who went out with us. They sign up and in turn will pick up another one who worked during the strike, and they’ll pick up another one or two.

Take Danny Lambert. He was bitterly opposed to the union and fought us tooth and nail and caused several fracases at the gate and was really vocal against the union. He joined in August this past year, and since then he’s signed up six or seven of the other people who were very vocal against the union. You can count on Danny to carry the union message in the plant. In fact, he told the manager right after he joined that all these years he’d been there and all the company did was lie to him and he’d better get on the side that would do something for him.

The union could not stop the layoffs and reduced hours caused by the recent recession. In early 1975, many Oneita workers were on only 2! Hours a week — seven hours on three days. TWUA attempted to get a week on, week off schedule so employees could collect unemployment the week they were off and maximize their incomes. The company refused, knowing that many would find other jobs before they were called back.

The recession also slowed plans for further organization in the Andrews area, because layoffs were very heavy at many plants. And the rapid turnover now in Oneita’s mills coupled with the open shop law in South Carolina makes building a strong union difficult, if not impossible.

Despite the continuing problems, the Oneita victory was tremendously important for all Southern workers. It showed that a union could organize textiles in the South and that black and white workers could and would stick together — at least in union business, if not in social relations outside the plant. It was the victory needed to take on J.P. Stevens.

Tags

Carolyn Ashbaugh

Carolyn Ashbaugh is a writer and film researcher in women’s labor history and the author of Lucy Parsons: American Revolutionary (Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co., 1976). (1976)

Carolyn Ashbaugh is a researcher in women’s labor history at Newberry Library in Chicago. (1974)

Dan McCurry

Dan McCurry is from a North Carolina textile mill family and currently coordinates the Food Coop Project at Loop College in Chicago. (1976)

Dan McCurry is from a North Carolina textile mill family and is now teaching farm/labor education at Loop College in Chicago. (1974)