Kate

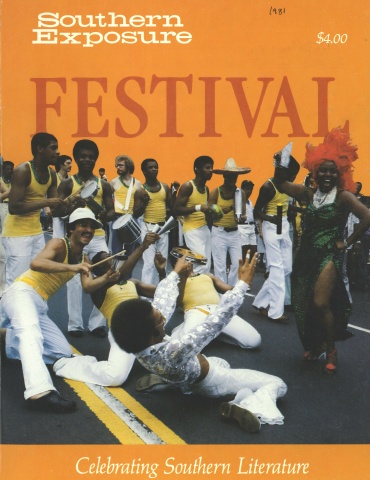

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

All her life, the woman had seen the mutilation of coal miners.

They don’t talk much about what did happen but rather what might have happened . . . if . . . say an inch to the right, maybe to the left. Up. Down. What if, and if only. Thank God and Amen.

And she would wonder what went on in a man’s mind as his body was ground up and spit out by some cannibalistic machine. She’d imagine the agony ripping nerves; flesh screaming. And with a shake, she would try to throw it off, to put her mind elsewhere. But just as her tongue keeps probing the cavity in her jaw tooth until it agonizes, she can’t release the thought . . . wondering. She is a coal miner.

One minute she is maneuvering the shuttle car to the face, concentrating on a smooth turn, the move of the machine, sighting a man who may be ahead, or an obstacle. The continuous miner groans in the next cut. The other buggy whines its way to the feeder. She feels content. “Happy” would be too radical a word. But things aren’t bad . . . with the day, the job, the life. She drives the buggy into the break, watching the front for obstacles, checking the base of the rib for power lines, sighting the turn.

An awareness of agony on the periphery tells her something is radically wrong. Turning her head, she sees the ripping flesh of her right arm, the snapping bones. This isn’t happening, the woman thinks. The canopy is crushing her arm. It moves towards her head. She is going to die.

The sudden alkali taste of death fills her mouth. Her system is not registering true pain, but it has gone crazy with the shock of torn nerves, bones systematically shattered. A nightmare of scarlet and black moves towards her head.

Animal sounds tear at her throat. She listens with the curious detachment of a spectator. Suddenly, it’s not happening anymore. The buggy has stopped. She is not going to die. But the rest of life has been dissected by that span of seconds.

“Oh my God! Somebody help. Joe . . . somebody . . . Aieeeeee. ...”

Her keening cuts across the suddenly still mine section, all machinery unexplainably stopped. From the other side of the canopy her right arm protrudes at an angle designed by neither God nor contortionist. Abstractly, she notices that the elbow bone which hangs loosely from the torn jacket looks like the knob end of a chicken bone, only larger.

“Oh, my God!” Voices echo her screams in disbelieving horror. “The woman’s cut all to hell. Earl! My God, Earl ... we gotta do something.”

The crew assembles and disassembles. Mange gags, and turning his back, heaves his lunch. Voices and people are thick but nothing is happening. They are trying to find where the power has been kicked to get the machinery off her arm, which is somewhere on the other side of the canopy post. She is not quite sure where. Torn flesh and bone fragments are visible through what was the sleeve of her hunting jacket. But she feels the arm elsewhere. Her senses position it high, shoulder high against the rib. But she knows that is a phantom limb . . . gone. Its ghost will ache in the damp. The specter will try to reach . . . experience. That’s what she’s read. That’s what the amputees say.

“Did you check the transformer to see if the power’s kicked there?” She can’t tell who is speaking. “We did. It’s not there.”

“How about the tricycle?”

“Bob was down there. He says no.”

“Christ! Maybe a bad splice. Could take hours to get her out.”

Joe presses a finger against the artery in her neck, grounding it against the collarbone. “We’re going to get you out of here, baby. You’ll be okay. We’ll get you right out.”

“I’m not pinned, Joe. It’s gone. Why don’t you just take it from one side and me from the other.” His eyes flatten at the thought. “Shh, now. We’ll get you out.” And turning, he screams in a voice that belongs to another man, “You guys get a jack. Get something, for God’s sake.”

For my sake, she thinks, settling into his arms. His caplight is the only illumination. They rest in a void of panic.

“There’s nothing on the jittney.” Leroy speaks in the midst of a sprint across the section, looking for something . . . somewhere. Everyone moves swiftly. No one does anything. Everyone tries. To stand still is to do nothing.

“Goddam!” Joe cusses, an extremity. “We’ve told them about bringing that mantrip in without a jack. Just a goddam good thing it’s on section.” He grinds his teeth, looking at her. It is hard for any of them to stand the sight of her body warped between the machine and the coal. It is hard for her. “Maybe we can get the power on. But what’ll we do? You don’t know what the hell’s wrong. The buggy could go the wrong way. It could take her head off.”

Dipperlip is there, two slate bars in hand.

“You gotta be kidding,” Joe says. “That thing weighs 18 tons.”

“We gotta try. We gotta do something.”

Dipper hands one bar to Marvin, the other bolter, and the two men insert the steel between the canopy and the rip. They pry, bars bending beneath their body weight. Tears and sweat mingle on Marvin’s face, streaking lines gorged by labor, marking the dust.

The machine quivers, then slides some little way from the rib. Hardly believing, Kate looks at Joe but he is concentrating on the buggy, willing it to move. Dipper strains, trying to eliminate the laws of gravity. Prayers are spit from between clinched teeth; eyes bulge with the effort.

“Now, in the hour of our need. His will be done . . . the shorn lamb . . .” Shorn, Kate thinks. That’s me.

The opening above her arm widens and she takes the bloody bit in her left hand and moves it upward, seeking an out. The buggy moves some little more. The flesh slips into the space. Free! She falls back onto Joe’s arms, the limb somehow attached.

For a moment, she feels a sinking. Unconscious? No. It is just the sense of relief spreading through the crew that reaches to her. “The stretcher,” Leroy says. “Let’s get her the hell out of here.”

From the backboard, Kate can see only dimly. Someone has removed her caplight and hardhat, which is another whole scene eliminated. Voices come to her darkly, through the passing light thrown by another. Shadows accentuate the unreality of a scene which must just be happening in her head anyways. Hell! She was indestructible. She’d spent the better part of some 20 years proving that. This is only a dream, shifting illusions of black and grey. Voices down a long tunnel.

Except for the pain. Her nerve ends have begun to scream. Torn flesh protests. Too much, she thinks. Too much. Pain builds on pain. Shock recedes. Reality and illusion are quickly separated. She lifts something. A fragment of bloody bone, and closes her eyes again quickly. She can’t stand the thought of being a victim.

“Easy now. Easy.” She is lowered. Joe’s hand compresses the artery, following every move, each dip and sway as they edge the stretcher into the mantrip. Wood clambers on metal and she is in. Dipperlip climbs to one side of her, his eyes brilliant in the coal-grimed face. And Joe is there, his ever-present hand on the jugular.

From the driver’s compartment, Leroy calls back, “You ready?”

“Everything’s okay here. You got clearance?”

“Tracks are open the whole way out.”

“Let ’er roll.”

The jittney clackets into life. The ride is fast and cuts whiz by in the blackness. Kate figures they could get outside in 10 minutes or so going this pace. The men’s silence also confirms the reality of the moment. Nothing less than a crisis would silence the horseplay and jiving that marks each trip outside, every escape from the blackness that is their working life.

Dipper shifts restlessly, eyeing the bloody attachment that was Kate’s arm, then looking quickly away. Joe is quiet but Kate can feel his heart in the arterial pressure, the firm touch. His heart is real through pain.

Such love starts the tears as Kate remembers the real victim of this accident. Her voice is hollow, holding nothing. “Jesse! My God! Oh, my God . . . what’s goin’ to happen to my baby. I want my baby.”

Joe pushes the hair from her face. “Shhhh, now. You don’t need to be worryin’ about that. Your baby will be all right.”

“Jesus,” Dipper mutters.

“But you don’t understand ... I need my baby.”

Shock, the two men are thinking, almost relieved. Their first aid training has told them to expect this. A person may talk quite lucidly and still be in shock. A woman wailing for her baby when she has her arm tore off. That’s crazy . . . shock. “Something on the tracks up there. Thought he called for clearance.” Kate feels Joe’s hand tense on her collarbone. She hears the screams from the front half of the jittney. “Injured man! Clear the tracks. Ignorant sons of bitches. Get the fuck out of the way.”

The vehicle hurls forward unimpeded. Whatever was there must have moved. Beside Kate, Dipper is talking. “General mine foreman . . . that damn Zanzucki. Did you see him run to move that mantrip?”

Both men are silent for the rest of the ride. A faint light creases her eyes. The pitmouth comes closer and she prays for daylight, pushes against the pain. Black becomes grey. The glare of daylight erases caplights. They are outside.

Kate closes her eyes against the sudden bright ness. Brakes squeal. People gather. Confusion. Faces peer into the jittney and disappear. Old voices merge with new in the same refrain . . . “ac cident . . . woman . . . arm . . . don’t know.”

“Where in the hell is that ambulance.”

“Christ, Leroy. Give ’em time. We only called about 20 minutes ago.”

“Look at that fog out there. Ain’t gonna be nothin’ movin’ fast in this shit.”

Kate opens her eyes, avoiding the faces, looking up into the sky. Sure enough, it is raining. That seems appropriate. The brightness that appeared sunlight when first leaving the pitmouth is a thick greyish mist, weeping steady rain.

A new voice cuts into her reverie . . . Lester, the company safety man.

“How did it happen? Anyone see?”

No one answers.

“Well, take her into the shop.”

Kate opens her eyes to study the flaking yellow paint on the jittney’s interior. “Fuck day shift” is scrawled there in red chalk. “Fuck Lester,” she thinks.

Murmurs have started now. “Found her wedged between the rib and the buggy.”

The voice continues. “. . . cut off. Pretty damn near. She’ll lose it. Conscious. Okay. Callin’ for her kid though.”

Who the hell else is there to call for, she thinks. The rain is cool on her face. She would have liked to linger under its ease, a request certain to be called shock.

But she is inside. The crew is still with her, jamming the small room, their hovering strangely protective. Authoritatively, Lester takes over. “Put the stretcher up on the table here. Sam, get me some scissors. I got to take a look at this.”

“Where’s your ambulance at, Lester?” Joe’s grip tightens on her shoulder. White, a mine com mitteeman, has appeared from somewhere and takes her hand, squeezing it to emphasize his presence.

“Should be here. Guess this fog slowed it down. Sam, phone the emergency squad again. Find out when they left. The rest of you get out of here. Give her some breathing space.”

The men filter out. Joe directs Lester’s attention to the need to compress the artery. Kate looks at the man as he leaves, trying to say . . . maybe thanks. Maybe that she loves him for his caring. He trails the crew out the door.

Lester keeps hacking away at the jacket while Sam calls on the phone to the emergency squad. “Yeah. Ambulance for a girl who has her arm tore off.”

Lester turns none too subtly. “Shhhh.”

“Comon, Lester. I know.”

He treads the verbal waters gingerly, the strain of it showing on his face. “Now, Kate, Sam was just gettin’ a little carried away. We don’t know that it’s gone and . . . you’re tough. You can handle it. We don’t even know what happened yet. What did happen?”

The son of a bitch, she thinks, meeting his look and holding it for a moment. He glances confusedly back at the arm. The jacket is almost off.

“Did it throw you.”

“I guess. I don’t know. It was so fast. That goddam buggy. My arm’s gone.” The tears are starting and Lester works quicker, somewhat flustered. “I need my baby.”

“Hold on now, Kate. I almost got this off.” His fumblings have a nervous cast and she glances down at the arm.

Red flesh. Prime sirloin. Unmarbled but charcoal crisp, packed with coal, lumps and dust ground into the muscle. No filet cut what with those bone fragments splintering the meat.

The supply room door flies open and she turns to see the general mine foreman. He approaches the table where she is laid. His walk indicates a maddened animal, wounded, who may attack. His eyes grab hers, then fall to the mangled limb. He looks up again in calculated horror . . . wondering. Worried. She knows his mind so well. He is trying to figure if he has covered his tracks, if this accident can come back on him in any way. He turns suddenly and bolts out the door. She hears him:

“Get those men back in the jittney and underground.” Sudden anger tears at the woman. For a moment there is no pain. She screams at his disappearing back, “You son of a bitch! The only thing you did give a damn about was your fuckin’ coal.”

Lester and Sam freeze, then quickly resume working over her arm.

Lester’s monotone suddenly accelerates. Excitement alters the pace of hopelessness.

“Artery’s still there! God knows how. Another quarter inch and it would’ve been gone. See it pumping. Right there, Sam. There, right behind that mess. They oughta be able to do something….” The sudden gladness in the woman is muted by the word “something.” She visualizes the many crippled miners she has known, fingers gone, arms maimed, limbs frozen at strange angles. She sees old Pete, trying to position his arm to light a cigarette. Ernie, dragging a crushed foot behind him. She sees herself, feeding the baby from some preposterous position, twisted arm, bound muscles.

A red flashing light bounces off Sam’s face, swings from wall to wall. “The ambulance,” Lester says, tearing jerkily at a blue paper package which expels a towel. As he places it over her arm, red splotches dot the surface.

“Here it is,” someone yells. The renewed confusion agitates the pain. As the nerve ends regain consciousness, she feels herself sinking. It is good; the blackness inviting. Temper the wind to the shorn lamb. Kate wanders the backroads of her mind. Dying will be a secondary shadow to the present. It will not be now. Kate knows this. Nor for a long time. But in its day, death will recognize its markings on her as ashes on the forehead, coal in the pores, flecks in the lungs.

She is being moved back through the weather into a glittering interior. White-coated attendants flash across her sight. And her brother’s face comes into view. Will! Somebody has called him out of the mine and now he climbs into the vehicle beside her stretcher.

“I’m goin’.” His words are gruff. Why not, thinks Kate. He is her brother. His ways are not hers but he will buttress her strength. She concentrates on fighting the pain, keeping it in her sights. If she quits looking, it will take over. If her attention swerves, the unbearable becomes worse.

The 40 miles to the nearest hospital stretch over pot holes and broken roads. Thick fog nudges the windows, trying to infiltrate the interior, obliterating the outside.

“Christ!” the driver complains, inching the vehicle along. “I ain’t seen it this bad in years. Not since that run to Jacobs in ’63. Remember that one. Picked up a boy who got eat up by the feeder. Kid didn’t have a chance.”

Confusion again. Trundling and bundling. In the eyes straining to see, Kate can read curiosity . . . shock. Pity. As always, compassion is the most difficult to endure. You can turn away from pity, but not compassion. And it will cripple you.

The emergency room nurses avert their heads as the arm is unwrapped, then look back. They stare at the gore, make a face, then look back again, deliciously horrified and fascinated. The doctor is blessedly brief.

“We can’t handle this. Make arrangements for transport.”

“Morgantown?”

“No. Try Union Pacific in Baltimore. They’re the hand center for the East Coast and if it can be saved, they’ll do it. Say we have a patient with a partially severed arm and a high chance of in fection. We need the helicopter for transport. Stat.”

A nurse cuts off the remainder of Kate’s filthy clothing, touching them gingerly. Another tugs at her boots and each jerk is agony.

“Cut the damn things,” Kate screams. She does so. The doctor sinks the first of so many needles in her good arm. She raises her brows in question. “Morphine,” he explains. “It should cut the pain.” It does nothing.

A nurse brings a rag to clean the wound. “Don’t.” The doctor’s voice is sharp. “Don’t touch that arm. Pack it in ice, start some i.v.’s and we wait.”

They didn’t wait long. “Fog’s too thick, Bal timore says. You’ll have to go by ambulance, Kate,” a doctor of heavy beard and kind eye tells her. “It’ll be a hell of a trip, I’ll not kid you. But we’ll send a nurse with you so you can have another shot. You’ll need it.”

She is back in the ambulance. Morphine blunts the pain and her awareness clouds. Still it is there, gnawing. Without site. Hurt envelops her body, centering in neither arm nor head. She wants unconsciousness but it won’t come. Her mind is too disciplined and grips reality despite herself. After three hours on the road, which seem like an eternity, Baltimore’s lights tint the sky pink. Despite the drug, the pain has escalated for the woman and now has a razor quality. The pas sengers in the ambulance are silent. Will grips Kate’s hand, his forehead sweatbeaded. The driver’s back tenses when she moans. “Supposed to be a police escort,” she hears him mutter. “Where the hell are they.”

“You’ll probably pick them up on the radio,” his partner advises.

Contact is made. The dispatcher’s voice echoes through the ambulance. “Okay, Fletcher County. You will proceed about a mile and a half to University Parkway. Make a left. I believe that’s at the third stoplight.”

“He believes . . .” Will growls.

Spotlights gleam down from a tall brick building: Pacific Memorial Hospital.

“Thank God,” the nurse says, detaching the i.v. as the doors are thrown open. Kate is lifted out, but again her senses register a difference. The hands are smoother here. Floors have a high polish. Lights are brighter; voices low. White coats unwrap the arm, evaluate, x-ray, page. A doctor removes most of the pain and most of her mind. “Move your fingers,” they say. “Make a fist.” “Lucky,” they say. “A strange break. You should have severed that artery by all rights,” they say. God and she mutually acknowledge each other.

An Oriental introduces himself.

“I’m Dr. Kim. I’m going to put you to sleep.”

His moon face beams against fluorescent orbs. She likes this man and smiles through the gathering dimness. He pats her cheek. “You don’t look much like a coalminer. Too pretty.”

“You don’t look much like a doctor.”

He laughs merrily, a Santa Claus in white and yellow. The needle is inserted in her veins. “Little stick,” he warns. She is slipping. She doesn’t want to go there but it pulls her back. The blackness returns; the mines suck her in.

Later they will ask Kate, “Do you remember?” She says “yes,” but it is an affirmation qualified by periods of dimness when things are seen dimly through pain. She didn’t know such pain exists. Nights are spans between the operating room, broken regularly as the last shot wears off and she lies there, waiting the prescribed interval for her next fix of demerol and oblivion.

The people in her world exist only from the waist up. Sweet smelling gas lulls her to sleep and she wakes in hell. They call it the post-op room but it is hell’s antechamber populated by monitoring equipment which follows her struggles back into life with beeps and lights. Nurses hover, monitoring the monitors. The sterile cold environment is designed to discourage microbes. It discourages Kate. Life doesn’t seem worth returning too in that cold aloneness. She wakes feeling frozen, teeth chattering. Every tremor pushes the pain through her body. Her mouth is dry and she looks up into the bright lights, knowing she is back for another go at it and wondering if it’s worth the effort. Licking her cracked lips, she finds even her spit has gone. Finally, she manages a dry call, “Water.”

The nurse confers with another nurse who pages the doctor. An eternity later, she rubs ice over Kate’s mouth, then allows her to suck a few chips. The woman’s system goes crazy. Parched cells stampede toward moisture. Little by little, each teasing drop is absorbed. Finally she is allowed a sip. Then a swallow. The dryness relaxes some. Her teeth chatter against the glass and she asks for blankets. She is packed in warmth. Her senses cease complaining and she relaxes some . . . enough for the pain to reassert itself.

“Could you get me something? I’m hurting pretty bad.”

“Not yet. Wait till they get you upstairs and check the doctor’s orders.”

“How long will that be?”

She checks her watch. “About an hour.”

After what Kate judges to be four hours, she timidly catches the nurse’s eye.

The nurse glances at her watch again. “I’ll call for transport.”

A half hour passes. Chances are that the floor nurse is busy catering to the needs of her patients and can’t find time to truck down to the o.r. Finally Mary, God bless her, appears and transports Kate, tucked in, medicated and soothed, back to her bed. The worst is over, at least till the morrow.

The doctors work to clean the wound before attempting any surgical connections. I.v.’s empty into her system, one clear bag following another. Glucose. Blood. Antibiotics. Her system disgorges fluids through a catheter into a bag whose yellow contents are a visible flaunting of her body’s wastes, the stuff mother had told her was nasty.

The third night ... at least, Kate thinks it is the third night . . . they set her bones. The doctor says they will use a Hoffman apparatus. She nods her head, comprehending nothing. And wakes to find a madman’s erector set perched on her arm. Eight pins, about six inches long each, have been drilled into the bone and interconnected. Fifteen pounds of metal rods, screws and bolts shape the fragments into some semblance of an arm. They tell her that this is only the second time such a device has been used on an arm. And they have never saved one “so far gone.” A year or two prior, they say, it would be in that box under the willow tree. Kate doesn’t feel particularly lucky then. She just feels the pain. They say in a few days there will be a skin graft; in a few months, a bone graft. A nerve graft. Amazing. . . .

Washing her, the nurses marvel at the persistence of coal dirt. Her hair fades back to a dingy red. Black slowly evacuates the pores. Grease and oil are rubbed away. But the dark halfmoons under the fingertips of her mangled hands persist, a personal affront to hospital hygiene and operating room sterility. Nurses scrub, fuss, scrape and cut. It does no good.

Kate’s consciousness remains borderline. The pain ebbs to engulf. She dips into oblivion and finds it waiting. Nurses try to position her for comfort and find none. Some become frustrated at their own helplessness, resentful of her pain. The buzzer is sometimes ignored or answered more slowly. Pain shots are given with a sense of relief. They know for a while the agony will back off and only minor discomforts need to be dealt with.

Through it all, there are the visitors. Sympathetic, well-meaning and conscientious, they come. And one must talk to them. “Now what exactly did happen? Harry heard. . . .”

The companionship she needs is those few who come and say little, holding her hand and pushing back the dimness. They generate healing with a light touch, require no response.

The six weeks of hospitalization pass. She recovers quickly, surpassing the doctor’s prognosis. They credit her stamina . . . toughness, they call it. But mostly she recovers because of Will’s new concern, Lindy’s willingness to shackle her life with Jesse, John’s quiet presence, but mostly because of a confused little boy who understands only that his mother has disappeared.

The baby is slow to accept her, fearing another betrayal. But they make their peace. Surmounting the new concern of her family for herself and the child is a little more difficult. Tasks done with one hand now require twice the time, if they can be done. But Kate knows she must do them. To become dependent will establish a precedent she will have to live with the rest of her life. She insists on returning to the farm with the child. It is easier to do the hard thing, to do it alone.

The physical limitations of the arm are learned with daily living. Pain ceases or becomes such a fact of life it is not noticed. But now she needs to find something to fill up the days, to fill up the rest of her life. They have told her she cannot go back to mining. There is nothing in Cogan’s Bluff but mining.

She learns to live with the mutilation by beating herself into fatigue each day, hoping exhaustion will bring an easy sleep. But three a.m. is the witching hour. Yesterday’s black fatigue has mellowed. Dreams wrap, entangle, ensnare. From behind her eyelids, the canopy grabs her arm, chewing it to the consistency of mincemeat. The hand jerks toward her, yanked by some severance while the machine grinds the limb into the rib. Snap! A bone breaks. The canopy closes in on her head. Snap! A clean cut across marrow and nerves. The hand flops in protest. She is reminded of a dying fish. Snap!

She jerks awake into the room’s blackness, like that of the coal, clutching her right arm. The elbow is frozen in a perpetual half bend. The skin is rough and mottled to the touch. But there, sweet Jesus. Warm and alive. Crippled and unsightly. But there.

Funny. The arm has more personality in disfigurement than when it was intact. She is continually aware of it being an extension of herself, having definite needs and wants. Her body caters to that arm. The back has donated skin. Nerves from the legs. Bone from the hip. Tendons . . . where in the hell did they get those tendons? The left arm works for its partner, attempts to write, perform the primary life functions.

She thinks during those long nights ... of what she will do and what she can no longer do.

The physical and spiritual ache dims as morning comes strong. She rises and takes Jesse from his crib. He stirs only slightly. Placing him on the right side of the bed, she slides in beside him and insulates the arm with his body’s warmth. Funny that this child she so recently nurtured within her body should already be sustaining her. She will have to buy a heating pad, Kate thinks. Tomorrow. Then she realizes it’s already tomorrow. In many ways.

It’s time to leave her mountains.

Tags

Barbara Angle

Barbara Angle was born and raised in the Maryland coalfields, is the granddaughter of a miner and went to work in a West Virginia mine in 1975. She has been a general laborer, longwall chocksetter and shuttle-car operator. This story is an excerpt from her new book, Kate. (1981)