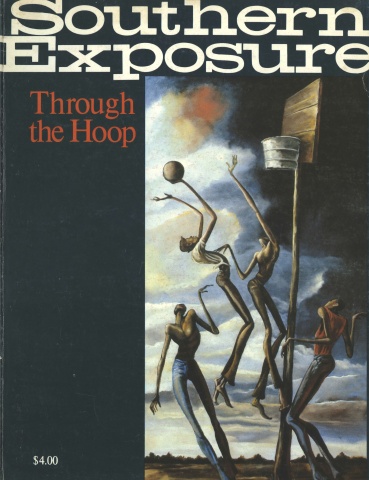

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

The material here first appeared in the Winter, 1976, Foxfire Magazine (Vol. 10, No. 4) and subsequently in Foxfire 5. The material was collected, edited and prepared for publication by Foxfire editor, Jeff Fears.

Daddy said, “Too late now. He’s gone.”

I said, “Maybe not.” I said, “I could track him.” I just wheeled and went back up there where he went off that log, and there, where he’d jumped off, was a track so big your hat wouldn’t cover it. You could see it just like a cow’s track, you know, where he’d jumped off. And when he went to walking, why you could see his track right on around through there just the same as a cow track.

The dogs had quit, so I just took its sign and was tracking it just like tracking a dog or a cow. I just left Dad. I never paid no more attention to him. And first thing I knowed, I walked right in on it! And he was in laurel as thick as your fingers. He was going right around the side of the hill from me. I pulled out my pistol and fired. That’s all I had was a pistol. A 38-special is what it was. Held nine shots. Well, when I done that, he just throwed his head up, turned, and was coming towards me.

I fell down and emptied the gun. I didn’t have time but to put two more back in the magazine. I had a pocket full of shells, but didn’t have time to put them in. That thing was a-getting so close I didn’t feel good waiting to put in any more. So I had two more shots, and the last shot that I fired, he jerked his head thataway and I hit him right in the lock of the jaw, and his mouth flew open, and you could have set a small dog in his mouth without a bit of trouble. And the blood just a-gushing.

I didn’t have sense enough to shoot over his head. He had his head down, if I’d gone over his head, I’d done good. But I didn’t. You just as well spit out there in the yard for all the good that’ll do to shoot one in the head. But when you’re in a laurel patch and you’re going in on him and he’s coming out at you, you don’t feel good. That’s the way that one was. He was close as that chair there to me, and I’d done made the will to run when Daddy slipped up behind me and said, “Where’s it at?”

And I said, “If you look right there, you’d see where it’s at!” And that bear’s mouth was open that big. You could have thrown a dog in his mouth.

Dad had a .30-.30. He jerked that .30-.30 in to his face, and when the gun fired, the bear just wheeled and right off the side of the hill he went and went over a cliff about 40 foot high.

When Mike Clark, the director of the Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee, and one of the members of the Foxfire Advisory Board, found out that some of us were interested in meeting some bear hunters, he offered to meet me, Danny Brown and Eddie Brown at his home place in the Cruso Valley outside Waynesville, North Carolina, and introduce us to some. His ancestors had been bear hunters, and so he had met many men in the area who hunted for sport and for the meat. He took us to meet Bob Burress, Glenn Griffin and Lenoir “Bear Hunter” Pless.

Several weeks later, Eliot Wigginton and I were on the road again, this time to check out some bear hunting information that had been gathered by another Foxfire student several years ago from Taylor Crockett, who lives near Franklin, North Carolina.

The bears that live in the Southern Appalachians are all black bears. Jerald Cogdill told us, “The average weight of the bears we kill is 200 to 250 pounds. A lot of people see one, you know, and their eyes get big and then the bear gets big too.”

The bear’s main source of food is the “mast” of the forest — hickory nuts, acorns and so on. They also eat worms, berries, grapes and insects in season; if hungry, they will sometimes venture down into communities to visit apple orchards or garbage cans and dumps. They rarely kill stock like sheep or cattle. Jerald said, “There’s one that killed a cow on 1-40 the other day because this year there ain’t much in the woods for them to eat. If they can get things to eat, they won’t generally bother animals.”

In the fall of the year, they do their main feeding for the long winter months, raking back the leaves to find mast, or even climbing up into the oak and hickory trees to break off nut-bearing limbs. Jerald said, “Before the apples start falling, if there isn’t a lot of mast in the woods, a lot of times you can check an apple tree and find where he’s climbed it by the claw marks. But usually they stay in the woods and hunt. They rake the leaves in there. Just looks like a bunch of hogs have been in there rooting around.”

The female will go to den in November or December if she has enough fat stored up to last her through the winter. If not, she’ll generally keep hunting, sometimes being forced to eat bark in the worst part of the winter. The male does not go to den, but keeps prowling. “In bad weather,” Bear Hunter said, “he’ll crawl under something or another — under a tree or a limb or something. Or if they ain’t nothing for him to get under, he’ll break laurel and ivy like a hog and make him a bed. I’ve found several of them in the summertime. Be a huckleberry picking or something and find them in them laurel thickets where they’ve just broke them and made them a pile as big as — well, I bet you can’t get what they break and pile it in this room right here. And they just crawl right in the middle of it and lay down there just quilled up. Maybe lay two or three days and get up and go on. Maybe another bad spell come and they do the same thing again. Never go to den.

“But the female always goes to den when she’s fat enough. Her cubs are born there in February and March. The mother will go out during these first spring months to get water and food, but she usually doesn’t bring the cubs out until up in April when it’s warm enough for them to follow.” By hunting season, the cub is usually ready to take care of itself and weighs about 50 pounds.

In the spring and summer while the cub is still following its mother, the mother is very protective. Bear Hunter said, “You better watch when they’ve cubs or little ones. They’re like a dog or a wildcat or anything else. They fight for their little ones. If you ever find a little one, don’t never try to catch him without you know it has got away from the mother. If he ever makes a squall [and she’s around], she’ll be there in a minute.”

A bear will range for miles hunting mast, but will generally stay in the same area where he was raised. Jerald said, “They sometimes range as far as 20 miles in one night. A lot of people won’t believe it, but they will. Bears will move until they find food. They have to.” Bears are not territorial in the sense that they fight to keep other bears out of their area. Sometimes there will be six or eight or 10 bears all feeding in one area.

Every hunter that we talked to agreed that the first step in any hunt was the location of fresh signs that would show where the bears had been feeding. Some hunters go into the woods around October first and locate signs in order to be ready to take their parties in when the season opens on October 15. The oldest hunters, however, would just go to the woods and camp, find signs and do their hunting all at the same time.

On the morning of the hunt, “standers” are put out on ridges overlooking gaps that the bear is likely to pass through once the dogs start chasing it. Once they’re in place, the dogs are put on the trail, and hopefully the bear is located, then either killed by one of the standers as it flees by, or treed by the dogs and held in one place until the hunters can get there and kill it.

The signs the hunters look for are such things as places where the bears raked back leaves looking for mast. If the nuts haven’t started falling yet, the hunter might find places where the bears have climbed up into oak trees and broken limbs trying to get to them. Bob Burress said, “We call it ‘lapping.’ I reckon what give it that name is a bear’ll just reach out and lap em in.”

Once the feeding area is located, the hunters are ready to begin. Taylor Crockett described the oldest style of hunting as follows:

“The younger men, they did the hard work. They got in the woods and made camp; and the older men, they furnished the brains for the hunt. [After camp was made] the younger men, or the men that were able, would go out and hunt signs the first day and come back and report. Then the older members of the party would plan the strategy of the hunt — that is, decide which way to drive with the dogs and where to place the standers. [The bear might] be laying up in a woolly head up a ridge. Well, he’d say, ‘We’ll jump it there in the morning; and if we come in from above, why, he’ll run west. If we come in from below, he’ll run north. And so we’ll put standers in such and such a gap that he’s likely to go through.’ And before they took the dogs out, they would send the standers on ahead to be there waiting.

“Now they might send the standers out five miles, and maybe the dogs would go the other way. [That stander] might never hear a dog all day. But he was supposed to stay there till up in the evening so if the bear happened to come that way, he’d be there. And if he left his stand or did something he wasn’t supposed to do, why, they wouldn’t take him hunting again. He had to go according to the rules.

“And then the drivers — they were the men that led the dogs through the woods to pick up the track — generally they’d have one dog that was bolder, better trained, and more experienced. They’d turn him loose first and let him get it straightened out, and then they’d turn the younger dogs loose one or two at a time on the track so they wouldn’t fight. They were so high-keyed that they just wanted to jump on anything they might run across. They’d jump on each other they were so excited and wanting to go so bad.

“But the older, more experienced dog is your strike dog. He generally has a little better nose and can smell a colder track. He’s maybe a little smarter. Won’t get excited and get off the track and lose it. And they use him to start the other dogs. And sometimes they’ll have a dog or two that just barks big mostly and doesn’t fight much. He just chases the bear, but they can hear him a long ways. Then maybe there’ll be another dog — sometimes they’ll use a mixed-up [breed of] dog — that doesn’t bark much, but he fights hard and tends to stop the bear. You need both kinds. A dog that won’t stop the bear is not much good, and one that’ll stop him but you don’t know where he is is not too good. So you use a combination — a team — gathered in a pack of six or 12 or 15. Seven or eight is enough, but sometimes you get men with you, and they all want to bring their own dogs, and you just keep adding on until you get, really, more than you need. I used to do better with just five or six old dogs that knew just exactly what they were doing. I’d hardly ever lose a bear.

“Some hunters will use their dogs such a long time that they won’t run anything but bear. You want them to lead the young dogs because the young dogs want to run deer or coon or just pretty near anything they can get after.

“Then the drivers, of course, fall in behind the dogs in case they stop the bear long enough for them to catch up — tree him. And the standers, they could tell by listening at the dogs coming if they were going to come close. If they were, they’d try to run in and cut him off — try to kill the bear.

“And it would generally take them a week for a hunt. Now, why, they just jump in a jeep and run out here, you know, 10 or 15 miles to hunt, and come back that same day. Not the same as it used to be. That’s the reason that the game is getting scarce. Too accessible.”

Jerald Cogdill is one of a number of bear hunters that represents a bridge between old and new hunting techniques. He and his partners begin scouting for signs two weeks before the season opens in the fall, and return home in the evenings since most of them have to be at work the next morning. When the season opens, they head for the most likely spot they have found [it is common for a man to set up his job at a local plant so that his vacations fall at the beginning of bear season], put out their standers, and bring in their dogs.

“And we use radios. With a radio, you can tell a man which way the bear’s going; and the man that’s like the stander up here, why, if it’s going through yonder, he’ll be listening on his radio and he might come back down here to where we turned loose at and get a vehicle and go around and cut that bear off.

“We use 11 dogs in all, and they know what they’re doing. You need six good dogs to get ahold of the bear — not ones to run along behind it and bark at it. You’ll never tree a bear that way. They’ve got to get ahold of it [and aggravate it until it stops running and trees].”

Bob Burress, like Jerald, begins looking for signs about the first of October. “You’ve got to go way back. The rougher the country, the better the bear likes it.” Glenn agreed, saying, “A bear can run within 20 feet of you in that ivy [laurel and rhododendron] and you can’t see him. You can hear him a-slashing it down, but you can’t see him. He likes that kind of country He’ll just run through it just like a horse.”

The men who are following the dogs, if they can keep up with them, have a better chance at getting the bear. They are really the ones who are in the middle of everything, and often they look down on those who prefer to be standers. As Bear Hunter said, “If you really bear hunt, you’ll run with the dogs unless you do like a lot of them does — get out [in a stand] and pile up and lay there while everybody else does the work. They’ll go to a stand and then they’ll stay a little bit and they’ll leave it, and maybe if you jump one, right through there he goes and gets away. I used to, when I could get about, when the dogs would strike one, that’s the way I went. I followed them. I stayed with the dogs.”

Taylor Crockett, who also runs with the dogs, said, “Bear hunting is the most rugged sport we have in the hunting line. To do it right, you have to be in good physical condition. You find the bear generally in the very roughest place that he can find. Calls for a lot of endurance and determination and perseverance. Just everybody’s not a bear hunter. Now there are a good many would-be bear hunters, but they just go out somewhere and park their jeeps on the road and listen to the dogs is about all they do. A real bear hunter likes to get in there with the dogs and find the track and turn loose on him. That separates the men from the boys is the old saying.”

If there are a large number of men on the hunt, then a decision has to be made as to how the bear is going to be divided up. Bob Burress told us of several methods:

“First we skin it out. We usually lay it out on a piece of paper and skin him out on the ground — just split him down the legs and start skinning him out. Sometimes we hang him to skin him. We start at his heels and skin plumb on out down to his head. Most of the time we don’t skin his feet. We just put a ring around his back legs and split it right on out. Skin right up his legs to his chin and then peel that off.

“Then however many men we got on the hunt — say there’s 10 men — we cut that bear’s hams up into 10 pieces and put them in 10 piles. [Then we cut the rest of the bear up the same way and distribute it among the 10 piles.] It’s divided just as equal as we can divide it, and then put into bags. Each man just goes and gets him a bag of meat.

“But now we used to just face a man against a wall there, and another man would put his hand on a pile and say, ‘Whose is this?’

“And [the man facing the wall would say], ‘That’s Stewart’s.’ He’d have a list in front of him and just call out the names [as the other men went from pile to pile].

“They said that 75 years ago, they put the meat in piles. Then they’d take a man, blindfold him, spin him around a couple of times; and he would point with that stick and say, ‘This is Joe’s,’ or somebody’s, so no one would be cheated. We’ve done that.”

Bob said, “A lot of the boys has tanned them bear hides and made them a rug. And we’ve sold a lot of hides. And we could sell them teeth, them tushes, for 50 cents apiece. And we’d take them claws and sell every one of them for 35 cents apiece. You’d be surprised at the amount of money that adds up to. We put it back in the treasury in the club and kept a little money ahead that way. But now it’s illegal to sell the hide. A lot of these tourists around Maggie Valley coming in, they was the ones buying them.”

After the bear is killed, one of the problems is to keep the dogs, who are highly keyed and excited, from fighting among each other. Bob deals with that problem this way: “We let them dogs wool the bear for about five minutes. Then we get the dogs off. You can easily get your dogs in a fight right there when you’ve killed the bear. It has happened. The dogs is mad. I mean they’re mad when they’re fighting a bear. When you pull the dogs loose, you have to watch out or they’ll snap at you. So after about five or 10 minutes, we start pulling the dogs back out and tying them up. Some of them you have to separate and put single because they’ll fight right there.”

As Jerald said, “For a hog dog, you want one that will catch and hold on because if he turns loose, that hog’ll cut him to pieces. But for a bear dog, you want one that will go in, snap, turn loose and come back. If he holds on, he gets killed because that old bear can reach around and get him.

“My brother had a dog that got his heart and liver knocked an inch and a quarter out of place. It took a 300 dollar doctor bill and it still ain’t no count. And I’ve seen dogs get slapped so hard they were addled for days; and another dog I saw got cut up like you were making shoestrings out of him. Of course, the only dogs you get killed are your best dogs. The sorry dogs hang back.

“We’ve had several dogs killed. Never had a man get hurt, but we’ve had a bear bite his gun strap. We’ll shoot one, and maybe the dogs’ll have it down, and it’ll get one of the dogs and start to bite it or something and we have to run in there and kick it loose and stick the gun right down against its head and shoot it so it won’t kill the dogs. I’ve seen them get a dog up and start to lay the teeth to them. Just pick the whole dog up and pull him right on in and pop the teeth to him. If they get ahold of one, they’ll tear one apart. That bear hunting’s rough. I like it though.”

Though there are many dangers involved, and a very real chance that dogs that have been worked with and trained for years will never hunt again, the excitement of the chase and the fight still makes it worthwhile for those men that have it in their blood. They get a good scare once in a while, but that’s all part of it. Taylor Crockett just laughs at the times he’s seen men scared:

“Of course, if you come in and the bear and the dogs are fighting, it’s more exciting because maybe you’re crawling through the ivy and you can’t see over 10 feet ahead, but you can hear the bear growling and popping his teeth, and the dogs hollering; and maybe you’ll see one get slapped and fly up over the laurel — bear’ll hit one and it’ll just throw it.

“I’ve gotten a pretty good kick now and then out of people I have taken hunting. One time I took some young men who were inexperienced but enthusiastic, and I said, ‘Well, now, boys, you all are young and stout. You can outrun me. So if we get after a bear, I want you to take after him just as hard as you can and catch up and kill him! ”

“And so we turned on a bear and they lit out in good style, and oh, they left me behind pretty quick. But I soon noticed that I was gaining on the boys. The closer we got to the bear, the slower they got. Just before we got to the bear, I had caught up with them. I could hear the dogs and it sounded like one hell of a fight. You could hear the dogs barking and the bear growling and the brush popping. And I came around a little turn in the trail, and there stood the boys. I said, ‘Boys, why don’t you get gone in there and kill that bear?’

“‘Well,’ they said, ‘we believe you better kill it for us!’ What happened was they got there and it kindly killed their nerve!

“And another old boy, I took him. He says, ‘Crockett,’ he says, ‘I just thought all my life about killing a bear.’ Says, ‘That’s my greatest ambition.’ Said, ‘If you’ll see that I get to kill a bear,’ says, ‘I’ll pay you extra.’

“‘Well,’ I says, ‘we’ll see what we can do.’

“And so that day we got after a big bear, and we had a good race, and the dogs stopped him in a little narrow ravine — just real steep-sided. Just ran up a little holler, and then he couldn’t climb out. He just run up against a rock cliff like, and the brush and ivy and rhododendron was real thick in there. “And this boy that was helping me with the dogs, we caught up and we could hear the bear down in there and the dogs fighting and the bear popping his teeth, and I said, ‘Get that old boy and we’ll let him kill this bear!’

“He ran back and got him and brought him up there. It was kinda open out in front of the ravine, but you couldn’t see back in there very well. That fellow ran up and down the bank a little bit, and he looked in here; and he ran up and he looked in there, and he listened a little, and he says, ‘Crockett,’ says, ‘I guess you better kill this bear.’ He just didn’t quite have the nerve to crawl in there!

“So that’s kinda the way you feel when you get there. Your hair seems like it just sorta rises up on the back of your neck a little bit, you know, and you get goose pimples. Of course, that’s the charge you get out of hunting. The excitement. If they wasn’t some excitement to it, why, there wouldn’t be any point in going.

“Couple of years ago, a young man went with me boar hunting. Hunting one that had been committing depredations to a cornfield. He could really get through the woods, and I told him to go ahead and try to get the boar, and he did. I heard him shoot, ‘Bang, bang, bang!’ I was pretty close. I went on. He owled [made a sound like an owl as a signal to let Taylor know where he was. A man would owl once if he wanted to know where you were, or three times if he wanted you to come]. I answered him. When you kill a boar, you shoot two shots about five seconds apart a few minutes after you’ve killed it so they’ll know you’ve killed it. He didn’t shoot any shots in the air. I got to him and the first thing he said to me was, ‘I guess I did something you won’t like.’

“I said, ‘What? Kill an old sow?’ We had not planned to kill any sows that trip.

“Says, ‘No.’ What he’d done was kill a bear. He was up there crawling around looking for a boar on the ground, and this bear jumped out right by him — lit right by him — out of a tree. And he shot all his shells up and killed him, and that’s the reason he thought he’d done something I wouldn’t like because it was out of season for bear.

“And I said, ‘Well, did it scare you a little bit?’

“And he rared back and says, ‘No-o-o-o-o! Not a bit!’

“And I just thought, ‘Well, now, that’s a lie.’

“And then after a while, he said, ‘Well,’ he said, ‘it did sorta excite me a little bit.’

“I can imagine.”

Tags

Jeff Fears

Jeff Fears is the editor of Foxfire magazine (1979)