Just Another Ballgame: Les Hunter and Leland Mitchell

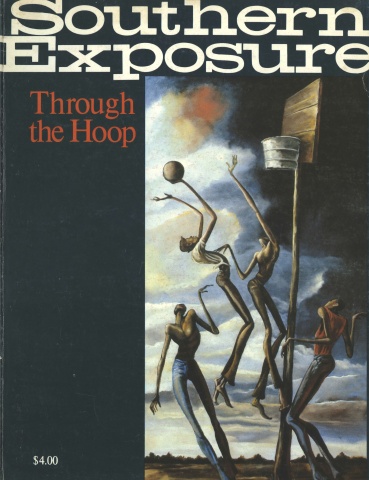

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

Introduction

In 1950, three years after Jackie Robinson cracked the color line in major league baseball, a little-noticed black man named Chuck Cooper did the same for pro basketball. College recruiting followed slowly and then exploded over Wilt Chamberlain. By the late 1950s, aggressive college coaches like UCLA’s John Wooden were actively searching for black ballplayers at the now-famous Rucker’s playground in Harlem and at the National Negro High School Championships in Nashville, Tennessee.

In 1960, Loyola of Chicago’s coach George Ireland recruited 6’6” Vic Rouse and 6’7” Les Hunter from the winning team at the Nashville Championships, all-black Pearl High School in Nashville itself. “Loyola had a so-so basketball team,” Hunter recalls. “We were highly touted to improve things right from the first, not because we had any high school All-Americans, no big names, but because we were all real big.” When Hunter was a sophomore, his team nearly won the 1962 National Invitation Tournament (NIT) in Madison Square Garden, and the following year they ranked third in the nation when the NCAA post-season tournament began.

The draw pitted Loyola, with four black starters, against the Bulldogs of Mississippi State, champions of the all-white Southeastern Conference. When the Mississippi team eluded legal restrictions against leaving the state to play in a racially integrated game, the national press gave the contest special attention. In Chicago, Loyola’s coach Ireland intercepted most of the postcards sent to his players signed “KKK” and worse, but he let the mail from Southside soul brothers pour in. John Bibb, sportswriter for the Nashville Tennessean who traveled to Ann Arbor to cover the game, recalls that “there were rows and rows of curtains to the interview area. You had to keep showing tickets every other minute to get in, as if they were expecting all kinds of trouble. ”

After trailing briefly, 7-0, Loyola came back to beat Mississippi State and went on to top another all-white Southern team, Duke, in the semifinals at Louisville’s “Freedom Hall.” In the NCAA finals, Loyola trailed top-ranked Cincinnati by 10 points with four minutes remaining but came back to tie on Jerry Harkness’ left-hander at the buzzer. They went on to win the national championship by two points in overtime. The team went home as conquerors to parade down Sheridan A venue.

But when the cheering stopped, Loyola’s stars were like millions of black Americans. Two years later, as Harkness now recalls, “I couldn’t get an apartment on the same street where I was a hero.”

In the nation’s schools, however, conditions were slowly changing. In the mid-60s, Les Hunter’s alma mater, Pearl High School, integrated, and in 1967, at neighboring Vanderbilt, another Pearl graduate, Perry Wallace, became the first black player to start for a Southeastern Conference basketball team. Now a Columbia law graduate working at George Washington University, Wallace recalls the hostility he faced at other SEC schools. “I heard a lot of racial jokes,” he told Nashville reporter Dwight Lewis recently. “At Ole Miss they waved the rebel flag. They yelled a lot of things I’d as soon forget. It was tough. Mississippi State was bad, too.”

Black players from the South who have now left basketball, like Pearl High School’s Les Hunter and Perry Wallace, are still watching intently for the changes which remain ahead. Wallace, for example, feels: “There may be a black head coach in the SEC someday, but presently there just aren’t many anywhere in college. A coaching job is an important leadership role, and universities put a lot of trust and money in that leadership role. It will require more faith than people often have in blacks today before a black person is chosen to be a head coach.”

Hunter is also observant of steps made, and still to be taken, in athletic and social integration. But he still remembers his endless workouts with hoop greats like Dick Barnett at the gym of all-black Tennessee State, and the three successive National Negro Championships he helped bring to Pearl High School in 1958-1960. “I was national champion four times,” he says proudly, “three times at Pearl and once at Loyola.” For Les Hunter, relaxing on the patio of his condominium in Overland Park, Kansas, the details of his basketball career are still vivid.

Striving for a Common Goal

Interview with Les Hunter

When I started playing ball — the fifth or sixth grade — I was real clumsy, kind of fat. Guys used to laugh at me falling all over everything. But I wanted to play so bad and I tried hard. I went to Washington Junior High School in North Nashville, about four miles from home. It was considered extremely rough over there. We’d get $1.50 a week to buy tokens for the bus, but I’d spend that. I’d end up walking or thumbing a ride. My mother didn’t like me to stay in North Nashville after dark. So she wouldn’t let me play in junior high school.

I did go out in the ninth grade, but I got cut by Mr. Tearsdale. He said I couldn’t develop because I was in the ninth grade already and he couldn’t use me. He told me to try out for Pearl’s team the next year because that way you’ve got three years to work with. Which I didn’t agree with.

So I started going out to Tennessee State and playing ball every day. They probably had the best basketball team in the country, but being an all-black school, were really restricted. They had Dick Barnett, Porter Merriweather, Johnny Barnhill — all ended up going pro. I went out there and played with them every day in the summers.

We played three-man whole court with no ventilation whatsoever. Coach McClendon would leave all the doors locked, all the windows closed, to get you in real good shape. He chose the teams, and if you lost on one court — they had three courts going all the time — you went on over to another and played right away. I can remember really being misused, elbowed. I was very timid. My folks had kind of sheltered me pretty much, and I couldn’t do a lot of things that the other kids could do. Looking back on it, I probably shouldn’t have been doing a lot of things.

The older I get and the more responsibility I have, I realize how much my parents really did for us at the time. They were born and raised right here in Nashville. They were uneducated, and my grandmother lived with us. At that time, we were middle class by any standards for blacks in the South. We owned our own home and had some income property from two other houses next door. My mother was in the mother patrol, the crossing guards, and was a housewife. My father worked at a chemical company as a laborer for 22 years before he got into ill health. I have two older sisters, and all of us were educated. Both sisters teach at Tennessee State. My parents have passed, my mother just last January. I’m really proud of them.

But I got over being timid. I was starting to get big, was able to bluff somebody. I learned how to fight back. Guys were getting a little scared. That gave me a little confidence. From then on, I think I was alright. Basketball is a combination of, first, talent. You need some talent: be able to shoot, play defense, be quick or something. But more than that, it’s a matter of developing pride. It’s something you have to feel. It’s got to be within you.

By my junior year in high school, I thought I had the starting center job nailed down. I could dunk. That’s when you’re starting to come around, when they know you can dunk. But Vic (Vic Rouse, another Loyola starter) moved here from East St. Louis, Illinois. He started at center and they moved another guy to forward that could shoot better than I could. I didn’t feel any animosity or anything. I played a lot, was even high point man quite a few games. Then my senior year, they moved Vic to forward and me to center. And we were winning.

We were really a family, unlike professional ball where you get a new friend every year. By being segregated, everybody was channeled straight into the same schools. We’d been together for 10 years. West and North Nashville had the best ballplayers. We ended up winning everything. Gupton, our coach, well, he’s a real fair guy. I don’t think there’s anybody in my entire life that has had more of an impact on me. He just seemed to be exactly what I needed at the time. If I went around and tried to sulk and mope, he’d come right there and kick me in the ass. He would hit you, pop you. He wouldn’t slug you in the face or anything. He’d maybe hit you in the chest or kick me in the tail. When he’d finished talking to you, you knew exactly what he meant.

They talk about the speech Knute Rockne made. Gupton gave a speech that I think’s unparalleled in the history of sports. It was 1959. We were playing (pro all-star) Eddie Miles’ team, Jones High School from Little Rock, in the finals of the National Negro Championship. We were at Tennessee State’s gym; the place was packed. The only whites there were a few scouts — George Ireland (Loyola of Chicago), Ted Owens (Kansas) and Johnny Wooden (UCLA). Down something like 16 points at halftime, we were playing real badly. There was a guy on our team who was very, very temperamental. He would sulk and wanted to fight a lot. His name was Harry Gilmore.

Gupton came in the dressing room and got real quiet. You couldn’t hear anything, just a loud silence. He sat there, and then he jumped up and just started talking. “I want to see one guy in this room smile. I don’t care how many points we’re down,” he said. “We’re gonna win.” He raised the level of his voice with each word. “I want to win by 10 points because we’re 10 points better than this team.” He was talking like in a roar. You could tell he believed so much in what he was saying that tears started coming out of his eyes. “And we’re here in Nashville and we’ve got everybody in the gym for us.” It wasn’t any uhs or buts or stutters. Words just flowing real eloquently out of his mouth at a real high pitch. “I want to win by 10 points. But I want to see this one guy smile.” We would have gone through the wall if he had said it right then and there. “I want to see this one guy smile.” We all knew who it was and we turned around and looked at Harry. And Harry broke out in a big grin.

We went out there and came back just like that. Pop, pop, pop. The game went into overtime, and we ended up winning by four points, 81-77. Never will forget it. Won the national championship. I’m positive it was a direct result of that speech. I wish somebody could have gotten that on tape. There’s nothing, nothing to compare to it. We won the national championship all three years at Pearl — ’58, ’59 and ’60.

There’s another thing that bothers me about the history books. They just completely ignore the things that blacks won when they were segregated. All the records are concerning whites. In Nashville, they talk about the state champion in ’59 or ’60 was Montgomery Bell Academy (white prep school) or something like that. We were probably the best team in the South, black or white. The year they integrated, ’64 or ’65, Ted McClain and those guys (Pearl team) went undefeated. Nobody came within 10 points of them. Just walked with it.

The key to our success was that we got along so well together. Our trips were by car, personal cars of the coaches. We split up the team and there’d be six guys in each car. We went all the way to Arkansas, and you know the size of basketball players. We had a lot of fun.

It was all segregation back then. But we played a game at the Central High School gym in Little Rock against that same Jones High team with Eddie Miles. Lots of white kids in the stands. Then we played in their gym. Jones High had the worst gym I had ever seen. If you shot from 25 feet out, your ball might hit the rafters. I betcha I saw 10 balls hit the rafters. I found out that’s how Eddie Miles learned to shoot his line drives, to miss those rafters. We played in gyms where if you went out of bounds on certain ends, you could run into a hot stove.

That’s one of the reasons I’m pro-busing. I don’t want to see anybody compelled in a free society to do any particular thing, but I think it’s a necessary evil. You’ve got so many facilities that blacks did not have access to that they have now. Even just a desk. How can you like somebody that you don’t even know? If it doesn’t work after you get to know people, then they’ve got a true opinion rather than something they’ve heard, some stereotype planted in their minds through childhood. You can’t ever really have integration unless a black kid knows a white kid. That’s one of the reasons why I left, why I didn’t go to Tennessee State.

We wanted to play on an integrated team. I didn’t want to go to an all-black school. I had been playing ball at Tennessee State every day. I felt I owed them something for giving me the opportunity to play at a level much higher than my talent, a chance to develop. But I thought of college as being a new experience, an opportunity to really get your teeth into life. I didn’t feel that I knew anything. Sitting in my house, if I turned the TV on, all you saw was white people. But you don’t know anything about them, how to mix or mingle with them. I never played against a white kid until my senior year in high school, didn’t even know any. I knew some people that my grandmother had worked for at a church but never any athletes. I think it was curiosity as well as figuring that, hey, here I’ve got an opportunity to get a good education, to find out more about how different people live.

Vic and I decided we were going to stick together because we felt we could make the nucleus of a pretty good team. If you want to call it boasting or bragging, we just felt that wherever we went, if we were together, we knew we had strong rebounding and good inside scoring. We were best friends, real close. We didn’t want to go to schools where we didn’t get as much publicity or play a big-time schedule against white teams. Coming from East St. Louis, Vic had played on an all-black team, but he still had access to a lot of different things. He was more mature at 17 than I was, and I think I leaned on him a little bit to help us make decisions. I had never been away from home prior to that.

I wanted to go to UCLA. Coach Wooden offered me a scholarship, but he wouldn’t pay my way back and forth to California. I found out later that they would have, but they couldn’t tell us that. This was right when the schools started giving the big money. As soon as white schools opened up for blacks, they started competing, offering under-the-table cash, cars, houses and all that. Houses for the family, you know. George Ireland had been coming to the National Negro Tournament, too. He’s a good salesman, sold my folks more than he sold me. Loyola was fairly close to my home. We could afford the bus fare back and forth. Vic’s parents were in East St. Louis — he lived with his relatives here — in Illinois, same as Loyola. I went up to see the campus, a very pretty school, a lot of ivy and all that. A small, personable campus. It was a total turnaround. The only blacks at Loyola were on athletic scholarship. There were a few others, but I’d say the school was 98-99 percent white. And Catholic. I was neither. It was a little drastic going to Loyola, because I still only saw one side, and that was the white side.

Two days after I got there, I started regretting it. I packed to go home a whole lot of times. I changed my mind cause I knew I’d have to sit out a basketball season at another school. I really had a miserable time. The only way I endured it was that we were able to ride around, from one end of the city to the other. All the blacks. The train — subway, the “El” — made a stop right in front of the school. We’d get on the train and go all over the city, just back and forth all night, just laughing at people. Get off and walk up and down the streets. Just to go through a black neighborhood is really what we wanted.

We had 14 on that freshman team, averaged 6’7”. But only four of us made it, four out of 14. Guys fell by the wayside or quit school or got kicked out or flunked. Even though you were an athlete out at school, there was a lot of prejudice going on at that time. They used to have mixers, a dance, in our dorm. We had a brand-new dorm, about 360 kids there. During the mixer, a kid from New York named Pablo Robinson — Pablo played for the Harlem Globetrotters until a year or two ago — asked a white girl to dance. This priest came up and said, “We don’t allow mixing or mingling.”

It was reflected in the classroom as well. Some white guys on the team were given better grades on their themes than we were, and some of them were less able to write. I was always good at themes during high school. I used to write them for other guys. There was one English teacher I thought was really racist. I got a guy who was getting A’s in everything to write a theme for me. He had never gotten a B in English class. He wrote the paper, and I got a C on it. There were some people who did the reverse, tried to give you good grades to compensate for bad grades you might get and get thrown off the team. There were a lot of good teachers.

The freshman players started jelling right away. I don’t think the varsity ever beat us our freshman year. Then our sophomore year, we would have won the NIT if there wasn’t a certain law or rule that even Loyola had. They would never play four blacks at one time, never put four blacks on the floor. Coach Ireland must’ve felt too much pressure on the school from the board of directors, the Dean, all that. We lost to Dayton, who then won the tournament with a real big guy named Bill Chmielewski.

In the consolation game, we played Duquesne with Willie Somerset. Ireland started four blacks for the first time. He put me back at center, Vic at forward and moved Ronny Miller to guard. We were out to show them that this is the way it should have been all year. We just waxed the game, really killed them. Just fast-breaking, catching it, pitching it out and going. I guess that convinced them, there was no question.

The following year (1962-1963), he just said to heck with all this addition. We played a lot of rag-time teams, and we played some real good schools. I think we ended up playing everybody that was rated in the Top 10. We lost at Bowling Green, with Howard Komives and Nate Thurmond, and we lost to Wichita in the last game of the season by one. We were 25-1 when we lost to Wichita and ranked number two behind Cincinnati. Then we dropped to number three and Duke, with the All-Americans Art Heyman and Jeff Mullins, moved up to number two.

In the first round of the NCAA, we played Tennessee Tech, who had won the Ohio Valley Conference. We beat them by 111-42, at that time the largest winning margin in NCAA history. Everybody was on us because in between giant killers, we were playing St. Norbitts of Canada and the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee Branch.

Then we went up to East Lansing and played Mississippi State. We’re feeling quite a bit of tension there because the papers are playing it up big, especially the racial confrontation type deal. When I was a sophomore, we had played in New Orleans and I had to stay separate from the rest of the team, at a black minister’s house. Then in Houston, when we were starting four blacks (just three weeks before the Mississippi State game), the fans had a cheer, “Our team is red hot; your team is all black,” and stuff like that.

Mississippi almost brings a startling concept to one’s mind because of what had happened. I think half of it started because of the word, Mississippi. But a sportswriter from Nashville, John Bibb, came all the way to Chicago to interview us. He didn’t ask about my basketball ability. He just asked, “What do you think about playing a team from Mississippi?” He let me know that it was a bigger issue than I ever imagined, a lot bigger than an NCAA game. So going into the game, I’m thinking, “This is like history.” At the time, I told Bibb, “Well, it’s just another ballgame.” But I really expected to be cursed, spat at and all of this. 1 expected the worst, and I was a little hesitant to do anything out of the way. I didn’t want to cause an incident. I think that really affected us somewhat. We’re playing four blacks.

Once you see that these guys are here just to play ball and try to beat you, you get all that out — probably like going on stage and performing. You’re nervous and tight from the start, but once you get into the natural flow of things, you don’t even think of the nervousness. You just concentrate on what you have to do to win.

Mississippi State was one of the most physical teams I played during the year. They were extremely physical, but nothing dirty. Nothing at all dirty. They played real hard ball. I remember Leland Mitchell. He was probably stronger than anybody on the team. He wasn’t that big, something like 6’4”, but he was solid. He was kind of like the Bailey Howell type — strong, persistent, played a lot of position. At that time, we were considered great jumpers. We hated guys to play good position because we don’t ever get to squat to jump, or make the dramatic leap. He was physical, a lot of strong arm and pushing around, but nothing ever got dirty. When we found a white boy that could jump, that was strong, that was physical, we’d say, “Man, it’s rough playing against some country white boy.” I guarded their center, but Mitchell guarded me.

They played a combination — switched zone and man-to-man. I didn’t play a good game against them. I had a good rebounding game, but only about 12 or 13 points. A low-scoring game. They hung in there. We were surprised that they would be that good. We didn’t pull the game out until the second half. 1 guess you always think a good black team can beat a good white team, especially at that time.

I was really amazed at the politeness that the Mississippi State players showed us. I think a lot of it can be attributed to Babe McCarthy, a fine gentleman in my opinion. Babe’s the kind of guy that always said what he felt and could put it in such a way that you wish you had said it. He was humorous, but he could get serious. Babe coached in the ABA, and we used to get together after games and have a few drinks. Country boys could put things so simple, not like doctors or professors who use 50,000 different words. Babe could say things with 10 words — one sentence.

I don’t think the Mississippi State game really had anything that significant as far as I was concerned. I was allowed to play against both black and white. The impact had to be on Mississippi State and their players, and what they had to face going back home. I want to find out their reaction to what happened when they went back.

The game and the situation did mean a lot to me though, because John Bibb had the balls to play it up in the Nashville papers. He put it in the headlines about Rouse and Hunter. Unless you were Wilma Rudolph (the Tennessee State track star and heroine of the 1960 Olympics) and had won three gold medals, it was the first time blacks had been in the headlines. When we won the national high school championships, there was a little clip, maybe 10 lines. John Bibb really opened up a lot. I was really proud of that. I’ve still got that article.

My senior year, we would have won if we had gotten by Michigan. We missed that on a controversial call, a traveling call on a basket that could have tied it and sent it into overtime. But instead, Cazzie Russell sank two free throws or a layup or something and we lost by four. Then I was drafted by the Detroit Pistons. They traded my rights to Baltimore, ironically in the same trade with Bailey Howell. I played at Baltimore one year; they wouldn’t give me a no-cut contract. So I went back to Chicago and finished up school, graduated. I was a case worker supervisor at a juvenile detention home in Chicago, the Audy Home. Counseled, set up daily schedules for kids that were awaiting disposition by the courts for some offense. When the ABA started up, I called Babe. He said he didn’t need anybody else, already had 40 guys. So I went with Minnesota and made the All-Star team the first three years of the league.

It was rough, but I wouldn’t trade it for anything. My first year in the pros, I didn’t know anybody, and guys would be moving back because they were afraid that I’d hit them with an elbow or something. But then you get to know a guy and nobody’s backing off. Once I got to know people in the league, just knowing them personally, you weren’t as intimidating to some guy. He knows that you might be a gentle guy. You just lose your effectiveness.

It was rough just carrying your clothes. You get up in the morning, pull off your pajamas and put on your clothes. You go and get on a plane, takes you right there so you can rest before the game. You pull off your clothes and jump into bed. Get back and put your clothes on just in time to go to the gym. You get there and take them off and put on your uniform. After the game you pull off your uniform and put your clothes back on. And you go to the motel and pull off your clothes and you go to bed. Next day, start all over and do the same thing. I ought to write a book named “Changing Clothes.”

I had different roommates, Artis Gilmore, some others. I always went back to New York during the summers. I lived right down the street from Julius Erving. We used to play ball every day at Nassau Community College. That’s when he was still in college. For a couple of years, I played in the Rucker League (Harlem league named for a community worker, the late Holcomb Rucker, and nationally famous for its high caliber of play and wide-open style). There’s nothing in the country that can parallel that. Maybe the dust bowl in Indianapolis where all the pros used to play, an outside court. You know Hoosier country is a big basketball area. At the Rucker League just about every game there’d be three or four thousand people there. People sitting in trees, vendors all over the place selling popcorn and hotdogs. It’s just a big event.

After the pros, I sold insurance for Prudential in Memphis. Sold a lot of insurance but wasn’t cut out for it. So I went into the restaurant business. Still selling, but I’m in one place, not running all over town. A friend and I went into the Steak and Ale training program for two years, to learn the restaurant business and invest our money. We got out, had hopes of opening our own restaurant. But promises were made that weren’t kept. I’m trying to get a group together to open up a restaurant out in Overland Park now. Black barbeque. If you can get it and franchise it, man, you got a gold mine.

A lot of whites think if you get a black you’re going to be instant winners — because “Man, blacks can play basketball.” Especially the first black athlete at a school, like Perry Wallace. Even though Wallace was a good player at Vanderbilt, they didn’t win. In general, I think the white public is getting an opportunity to see graceful athletes in action. I think they really appreciate it. Contrary to what some owners feel — that they’ve got to glamorize the white kid and make him a superstar. When a white star comes along, it’s money in the bank because the general public is white. When you get a Paul Westphal or Rick Barry, it’s gold. The problem I see is trying to glamorize a white boy for the money when he doesn’t have that kind of talent or when there’s enough talent that’s as good already on the team.

Basketball is a matter of developing pride. I think that athletes have a certain amount of pride and a certain amount of concentration on what they are trying to achieve in that particular sport. I think they are looking at performance rather than who they are participating against. Even if it’s black against white, they look at trying to pit their talents against someone else’s talents. I don’t think you can find any better friend or any better way to talk to each other than to be on a team with somebody because you’re striving for a common goal.

I think the sports arena is just that, a sports arena, not a political arena. Sports should be the one institution that should stand religiously above all this other. It should be the one point in time when nations get together and piss on politics and just go for pure physical and mental exertion. Sports has done more than any institution anywhere — more than any civil rights movement or anything — to break down racial barriers all over the world. Racial and political barriers. If you’ve got some players, come on, let’s play. Let’s compete. I would play South Africa as soon as I would play somebody from Missouri. And I’m from Kansas. Come on, let’s go. Bring your ball and uniform, and let’s play.

The Sheriff was a Basketball Fan, too

Interview with Leland Mitchell

In September, 1962, Governor Ross Barnett appointed himself registrar of the University of Mississippi in Jackson and refused admission to a black man, James Meredith. Encouraged by such leadership from above, white resistance to integration escalated rapidly, and on the night of September 30, federal troops and guardsmen, called out by President Kennedy, fought raucous students and Klansmen. Two people were killed, scores injured. Meredith started classes safely, but tensions within the state were high.

When the race issue flared again the following spring, Mississippi State University at Starkville became the focus of attention, and this time the white student body lined up in opposition to Barnett. Their high-flying basketball team had just won the title in the strong but segregated Southeastern Conference (SEC) for the third straight year, and the Bulldogs of Coach “Babe” McCarthy were eager to go to the post-season National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Tournament — even if it meant competing against black opponents for the first time.

“Our going to the NCAA,” the team captain told a newspaper, “would make the whole state of Mississippi look less prejudiced.”

Suddenly the underlying links between sports and politics had risen to the surface for all to see. “If Miss. State U. plays against a Negro outside the state, what would be greatly different in bringing the integrated teams into the state?” asked the Jackson Clarion Ledger on March 6, 1963. Invoking the domino theory so familiar in racist editorials of the time, the paper continued: “And why not recruit a Negro of special basketball ability to play on the Miss. State team? This is the road we seem to be traveling.”

It was not a road Governor Barnett was willing to accept. Limited by the legal aftermath of riots at Ole Miss, he was depending on his handpicked Trustees of the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning to keep the team at home and the state safe from integration. But Mississippi State President Dean Colvard, responding to campus pressure and bolstered by petitions from alumni and fans across the state, broke tradition and announced the team could go to the NCAA, beginning with a regional playoff game at Michigan State against Loyola of Chicago. When Barnett’s cronies demanded a hearing before the statewide Institutions of Higher Learning, picketers appeared at the meeting with signs reading, “Don’t confuse the NAACP with the NCAA,” and white resistance was defeated by a vote of eight to three.

With time running out, the powerful segregationists resorted to a familiar tactic. “We were all listening to the radio,” one player recalls, “when a bulletin said a state senator had got a court injunction. I will never forget Mitchell saying, ‘Who all wants to get in my car and let’s drive to Michigan State? By golly, 1’m going.’” Though white undergraduates had violently protested against integration at Ole Miss six months before, students in Starkville now hung in effigy those who dared enjoin their ball club against leaving the state.

When the showdown came on Thursday morning, March 14, the Oktibbeha County sheriff failed to serve an injunction on the group of tall young men with crewcuts and flat-tops who boarded the Southern Airlines plane in Starkville. Newspaper accounts referred to a late flight and schedule mixups at the airport, but recent sleuthing reveals another explanation: the sheriff too was a basketball fan and had graciously left the airport in time for the players to make their plane without a fight!

The Mississippi State starters making the historic trip were all small-town boys from low-income families. Red Stroud (6’1”), the SEC’s most valuable player, was the son of a bricklayer from Forest, Mississippi. Doug Hutton, the 5’10” guard with a behind-the-head dunk, had grown up in Clinton, where his father worked as a janitor. Bobby Shows, the 6’8” son of a teacher, hailed from the metropolis of Brookhaven, a town of 10,000. Captain Joe Dan Gold (6’5”) came from farthest away, having grown up on a farm near Fairdealing, Kentucky. The fifth tournament starter was number 44, 6’4” Leland Mitchell from Kiln, Mississippi.

Until he fouled out with six minutes and forty-seven seconds to go, Mitchell guarded Loyola’s Les Hunter, edging him in rebounds, 11 to 10, and in points, 14-12. But Loyola, a run-and-gun team averaging 100 points a game, proved too tall and fast for the slowdown specialists of Mississippi State, who depended on the now-famous four corners stall and shuffle offense. The Chicago quintet broke the game open in the final minutes, winning 61-51, and went on to upset Cincinnati for the NCAA title. Despite defeat, the Bulldogs returned to a cheering homecoming, participants in one of the least-remembered, but most ironic and highly significant, episodes in Mississippi’s civil-rights revolution.

Now, more than 16 years later, there are black players on the Bulldog basketball team, and black students make up 13 percent of the 8,700 undergraduate student body at Mississippi State. “I think there are more blacks at Mississippi State than at any other SEC school,” says Ray White, a current Bulldog starter from Gulfport.

As for the starters on the 1963 team, most are now active in coaching or recreational work in the area. One of them, Leland Mitchell, has become a successful Starkville developer. He began an aggressive real estate practice, turned a cotton field into a high-class suburb, and now lives in a $200,000 home. Here, sitting on a plush couch, he reminisced recently about his trip to the NCAA.

There wasn’t any problem about us not wanting to play. There were some petitions circulated around. A lot of signatures for us to go. We weren’t asked our opinion. We all wanted to go and the coach knew that.

The two state senators filed an injunction to stop us from going. We didn’t really understand what an injunction was. We were going to play if we were allowed to play and we weren’t if we weren’t allowed to. We didn’t really understand what an injunction was. The fans, the people that supported basketball in Mississippi, wanted us to play. We all wanted to go. It wasn’t a question of us trying to break the law. I’m sure that there weren’t any of us on the team that knew what an injunction was to start with. The fans, the people that supported basketball in Mississippi, wanted us to play.

Loyola was a good ball club, obviously. I think it hurt us a little bit, not practicing and not playing any games prior to the tournament. The indecision about whether we were going hurt us. We were a little rusty. We had as good a ball club as they had. But in a tournament like that where you got one time to go, you know, that’s it.

We didn’t shoot well. Joe Dan got his arm broke, a small bone. He didn’t know it until after the game. They had a good, quick ball club. We were told they pressed all over the court and we’d have trouble getting the ball down court. We didn’t think we would. Nobody’d been able to press us before. We had so much speed and quickness. They pressed us the whole game, but they never once caused a turnover, not once. Doug Hutton could go either way, left or right hand. They’d overplay everybody to the right, so Doug would just go left.

We were in the ballgame all the way, led most of the first half. We slowed it down some in the first half, and then went back playing. We could play either way. It didn’t matter. If we got behind, we could run. They were bigger than we were. They had Rouse and Hunter, big men. We were 6’3” and 6’4”, and they were 6’7”. They were bigger than we were, but we were quicker than they were.

Not much difference, you know, in a close ballgame. One shot missed or a bad pass or something. With about eight minutes to go, it seemed like — I forget how much time it was — I got the ball and turned to shoot and took a dribble off to the side. A guy come into me and they called an offensive foul. My fifth foul. We were one point ahead or behind when I fouled out. It was a close game right to the last minute.

In the consolation game, we beat Bowling Green, who had Nate Thurmond and Howard Komives. Bowling Green had beaten Loyola that year. I played against Jerry Harkness and Les Hunter in the ABA. We didn’t get to know them, but we remembered each other. We knew their names.

I think that whenever anybody excels at something, you’re looking at an individual. The fans are supporting the school and whoever represents the school — the individual player. On my Little League All-Stars, I had two black players and they both played. They’re both good little athletes. One played on my regular-season team. I just looked on them as an athlete and not whether they were black or not. I see sports as having some impact. One thing that has happened, the white players aren’t participating like they used to. When they integrated, the little white boys quit participating, especially in basketball. We’re just now seeing it at the college level. That’s why Mississippi State has mostly black players. Most of the high school teams are black. Athletics is something you can participate in for recognition in your teen years. Some get recognized by wearing nice clothes or driving a nice car or something like that. The poor families that live in the country. . . . Athletics gives blacks a place to go. Today, the white children ride everywhere. If they got to go three blocks, they ride. Little black children, they don’t have cars. They walk or run.

It’s an economic thing. Most of your good athletes in my lifetime came from poor families. White athletes came from poor families. Your good black players came from poor families, too. It’s no different. Good, well-to-do whites might have participated in athletics, but they had a car to drive when they were 15. They had other things to do, activities other than athletics. It’s economics still.

Tags

Bill Finger

In 1963, the year Mississippi State faced Loyola in the NCAA, Bill Finger was playing high school basketball in Jackson. He is now a freelance writer in Raleigh, NC, and at work on a book about the players of those historic teams. (1979)

Bill Finger is a writer in Raleigh, NC. (1978)

Bill Finger is the labor editor of Southern Exposure. (1976)

Bill Finger is the Director of the Institute for Southern Studies Textiles Project. He has worked for the North Carolina AFL-CIO and the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina. (1976)