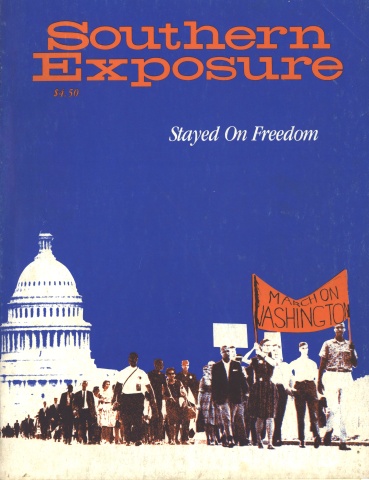

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

The National Guard stood at the entrances to Tuskegee Institute. We stopped. Somehow the guards mistook my grandmother’s nod to my cousin to drive on through Lincoln Gates as an acknowledgment to them. They nodded to her. It disconcerted me. My grandmother slightly turned her eyes to them with a pleasant, yet placid, smile as my cousin drove on through the gates.

I blotted out the military salutations. I had been taught by my father to always courteously dismiss whites in authority uniforms; otherwise, depending on their personal situations and moods, it could mean serious trouble for a Negro. I smiled to them, like my grandmother, as my cousin drove on to James Hall.

Later I learned that the Guard had been called up because Negroes were exercising their new 1954 legal right to attend the white public high school in the Tuskegee community. These Alabamian Guards, who in the main probably supported the segregationist Governor George C. Wallace, were asked to protect Negroes from the segregationists.

Why the Guard presence in a county with a population 87 percent black? Surely we, as citizens, could carry out the law of the land.

My search for answers led me to the periphery of a very small, close-knit underground student movement. I read Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, a former student at Tuskegee Institute, and wondered why he was not on the faculty. I met Dr. Paul Puryear, a political scientist, who was undergoing polite ostracism by his superiors in the administration. Everybody said he was a scholar, an intellect — an exceptionally brilliant teacher. His only infraction was that he dared to venture from the sanctuary of the Institute to vie in the mayoral election downtown, the province of the white city fathers.

The underground movement clandestinely circulated leaflets; quietly exchanged ideas and discussed the matters of the day over chess boards; eagerly kept abreast of African developments towards independence; envisioned what it would be like when the sleeping “model city” woke up to the nightmare of black reality in white America.

The Guards left in the quiet of the night. So did Dr. Paul Puryear. Our movement scored a victory and suffered a monumental loss. I did not know that an unconscious deal had been effected until years later.

I became a cheerleader. When not studying, my thoughts created intricate patterns to cheer the Golden Tigers on to victory. I divorced myself from the fact that my grandmother’s house was the home for freedom fighters. I put aside my sit-in and Freedom Ride experiences. I obliterated the sight of the Mother’s Day Massacre when Freedom Riders met the onslaught of Montgomery’s own “national guards.”

The contradiction of separating college study from social consciousness was revealed when I discovered that the library had limited resources on sexual behavior theories. My “Marriage and the Family” research paper encountered institutional limitations. Granted an audience with a vice president, I suggested we use an $80,000 donation to the Institute to buy books for the library. I was told that this could not be done since the gift was earmarked for a reflecting pool which could be transformed into an outdoor stage. This first encounter with an absentee, rich liberal via a Negro intermediary defined for me the neutralizing role of whites who, through their philanthropy, sugarcoat and shroud racism.

The reflecting pool is a sore sight on campus today. The library is still not only in need of books, but is in dire need of fundamental renovations.

Tuskegee’s budding young adult-children came home from the New England prep schools. It became abundantly clear that rubbing shoulders with upper-class white kids activated their thirst for black freedom. Immediately they made fast friends with their community childhood classmates whose parents could not afford to send them to prep schools. The invisible man came up from his subterranean existence.

This coalition organized themselves into the Tuskegee Institute Advancement League (TIAL). TIAL beseeched the long-standing Tuskegee Civic Association (TCA) for organizational inclusion, but the concept of coalitions on a particular issue was incomprehensible to the TCA at the time, though they had successfully won a gerrymandering case before the Supreme Court.

TIAL drafted its own program:

• We will assist other organizations with voter registration projects.

• We will conduct Freedom Schools in Fort Green, Little Texas and other outlying communities.

• We will establish an office and tax ourselves for the rent.

• We will fight for summer jobs downtown so students won’t have to go north to earn money for school expenses.

• We will monitor and participate in city council meetings.

• We will assist with freedom organizing efforts in Dallas and Lowndes Counties.

• We will join with others who are fighting for freedom.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) accepted our platform. The student body president, a New Yorker, gave up his responsibility as TIAL became more and more a legitimate voice of student sentiment for action. TIAL thus provided the leadership for 1,500 activist students out of the total enrollment of 2,300.

This student mandate to TIAL was granted through the bus ride to Montgomery to petition for the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Bill. The student body en masse, despite threats of expulsion from the administration, accompanied TIAL on that historical pilgrimage. The campus changed into a ghost town after students received brown-paper-bag lunches of an apple and a bologna sandwich dispensed by cafeteria workers. The Invisible Man multiplied into visible wo/men as they rode to the citadel of segregation and repression, the cradle of the Confederacy, singing freedom songs to fortify the righteousness of their actions.

The students, assembled before the State Capitol, dispatched their appointed leaders to attempt to see Governor Wallace. When police officers’ billy clubs battered the heads of several students, the students immediately sat down in the streets and sang freedom songs. The ridin on high to freedom had plummeted to the sinkin on low of what it means to be black in Alabama. The moral purity of the students’ purpose, protected by their enthusiastic singing of freedom songs, warded off the enveloping gloom that black people’s freedom was not on Alabama’s agenda. The actions of the FBI left us wondering if we, as a people, were even on the nation’s agenda.

The student leaders dispatched to arrange the meeting with the governor were not permitted to join the group. They shouted out that the governor would not meet with the delegation nor would he accept the petition. As the students attempted to read the petition to a nearby FBI agent, they were arrested for standing on state property. A hard core of about 300 students vowed to sit-in in front of the Capitol until Governor Wallace decided to meet with them.

The pilgrimage had started out with naive, idealistic students marching for freedom. Fourteen hours later on a chilly March night, the 300 emerged as insurgents.

The students sought refuge at the nearby Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, the famed black church where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., pastored, just one block from the State Capitol. It was after midnight. Exhausted and chilled to the bone, students sought sleep on the floor, in the pews — wherever they could lie down to rest.

The toilets would not flush; there was no water; there was no heat; there were no lights; the Deacon Board had had the utilities cut off. Outside, the law enforcers encircled the church, a rude awakening for the new insurgents. Finally, students from Tuskegee Institute and Alabama State came and, standing as a buffer between us and the police, called us out of the church. Their strength made us feel safe to leave.

The Montgomery experience gave birth to the scholar-activist concept. Tuskegee Institute had to reckon with this blossoming insurgency. The faculty who financially supported the pilgrimage went underground to avoid Puryear-type reprimands for their advancing the freedom calls. They became the new invisible wo/men.

The first order of business when the students returned to the campus was to halt “business as usual.” A moratorium, as it was called, was declared. Students presented demands to faculty and administrators: first, students were to be included, in a fundamental way, in campus governance; and second, students were to continue their activism on and off campus with instruction and faculty complement. Jennifer Jones, a biology major, summed it up: “There is no need for me to study bacteria pathology if I can’t do something about the well water in Little Texas.” Students, faculty and administrators did not resume pre- Montgomery interaction. Tuskegee’s adult-children became adult students, preparing themselves to impact on the nation and the world.

After serious thought, I decided to run for the student body presidency on the theme: “Total Representation for the Total Student Body.” I made special appeals to African and other international students, to married students and to campus- wide organizations like the YM-YWCA. My campaign was well-structured with a line-item budget. My campaign manager — now a human relations officer in a Connecticut city — advised me to make my campaign signs out of wood with waterproof paint.

The Board of Trustees was coming to Tuskegee Institute for its annual meeting on Founder’s Day. Student candidates were summoned to the president’s office and asked to take down our campaign signs. I asked why and was told that the signs had become unattractive as a result of the previous rain spell. Surely I was to be excused since my wooden signs with waterproof paint had not been damaged by the rain. I was told flatly that all of the signs, including mine, had to come down. I refused. The following day I presented a petition with well over 1,000 student and faculty signatures supporting the right to keep all of the signs up. The other candidates removed their weatherbeaten signs. I kept my signs up. I am convinced that the sign incident delivered the 75 percent mandate for me to serve as their president. The invisible man came above ground again.

On another front, the extraordinarily brilliant dean of students, Dr. P.B. Phillips, who had excellent rapport with students, was awarded $2.5 million from the Office of Equal Opportunity for his Tuskegee Institute Community Education Program. This meant summer jobs for many of the scholar-activists. Tuskegee was in the making for a long, hot summer.

Students pressed for summer jobs with downtown merchants to no avail. Picket lines immediately went up at the Big Bear supermarket. We had rotating picket lines. Wendy Paris used his father’s “freedom truck” and other students their cars to carry students to and fro on the hour so classes would not be missed. We conducted Freedom Schools in the county and assisted folks in registering to vote. The registrar was always recalcitrant to enforce the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Gaining experiences in Lowndes and Dallas Counties, a student delegation, spearheaded by Sammy Younge, Jr., went to Sunflower County, Mississippi, to learn the workings of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party . Other students tested the 1964 Public Accommodations Act and filed complaints against businesses which still refused to serve blacks. Others attended city council meetings, and when one of the members stonewalled appropriations to construct a low-rent housing complex, a picket line went up in front of his bank. Study groups on African liberation blossomed, with African students leading the workshops and the cultural exchange programs.

A freedom house was rented for full-time organizers. The TIAL office added another line to its already busy phone. We continued sit-ins, wade-ins. Students were arrested; we posted bail. Movement activity became as routine as going to classes.

The administration asked us to ease some of our civil-rights activity. White/Negro interaction was approaching model human relations, we were told. The students decided to test this notion. The Presbyterian Synod had passed a resolution that church services should serve all those who wished to attend. We asked a well-established black Presbyterian if she would worship at the white church in Tuskegee, Alabama, and invite them to attend her Presbyterian church. Fortified with the Synod resolution of good will, she agreed. The following Sunday white Presbyterians/Christians put her out of their church and slammed the door in her face. Soon afterwards, the students received even more underground support from Tuskegee’s Negro middle class.

White tensions mounted and finally erupted into violence. The white vigilantes attacked us with bottles, chains, baseball bats. The vigilantes mercilessly beat a white exchange student from St. Olaf College in Minnesota. He had polio and could not run, thereby becoming a victim in the bloodbath. Black students rushed to his rescue, battling vigilantes in the process.

I was summoned to the president’s office. I was not to encourage nor to lead the next Sunday’s march to the churches. I replied that the march would go on with or without me, and that the administration had overestimated my control over students. There was genuine concern for the students’ safety. I concurred, and suggested that if the Institute’s officials would lead the march perhaps the vigilantes would not attack us. Getting only a baffled look, I agreed with TIAL that the Deacons for Justice out of Bogalusa, Louisiana, would be a better assurance for the students’ safety. As the Deacons imperceptibly escorted the students on the march to the churches, whites timidly gawked at blacks driving pick-up trucks in the legal shotgun style. The march was peaceful, without incident.

Summer finally came to an end. Students welcomed the vacation to go home to rest.

Five students were threatened with expulsion stemming from a collegiate prank. Athletes were not awarded their promised scholarships. The financial aid officer was surly and slow. Male students burned down the barracks as unfit dormitories. All this occurred during the first week of the fall semester of 1965.

Student leaders met to map out our responsibilities. Some TIAL students worked in the student government office with me to handle campus activities and grievances, while others continued the work in the county. Sammy Younge, Jr., served as liaison between the two formations.

A student judiciary board was established with a student defender; the students who had committed the prank were placed on disciplinary probation by their peers. Athletes were given contracts to include hospitalization coverage. A picket line surrounded the financial aid officer, and he finally granted a conference with student leaders to see how we could facilitate the financial aid process. Male students moved into other dormitories.

TIAL community organizers went to Lowndes County on the weekends to assist in the newly organized Lowndes County Freedom Organization, which had the black panther as its symbol. Their work in Lowndes County became the source material for their classes in political science.

The speakers’ bureau, previously handled by the government. Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, Herbert Aptheker, Lonnie Shabazz highlighted the ideological spectrum of ideas. Odetta, Olatunji and Ramsey Lewis integrated the established vespers of concert pianists, aria prima donnas, the American ballet and chamber musicians. The student paper, the Campus Digest, was in the very capable hands of Peter Scott. He was an exceptionally analytical student journalist who placed events and actions in a larger perspective. I can still see his headline editorial when students decided not to culminate their homecoming parade in the downtown square: “Pomp and Circumstance.”

The student cohesion baffled the administration. They no longer attempted to divide the students or to sneer at their seriousness. Middle-class Negroes attended student meetings and offered input. Students were invited to faculty homes to explain the new assertiveness. Students evolved from complacent Negroes to blacks who not only wanted solutions to racial inequities, but who wanted to help plan the resolution. Students desperately wanted their elders, their models, to understand this development and to share in the growth. They were the future chemists, veterinarians, lawyers, political scientists, agriculturalists, journalists and educators who had consummated their scholastic achievements with the conviction to struggle for the freedom of our people.

The Tuskegee Institute students read passages of Alexis de Tocqueville in history and political science classes; they read Gunnar Myrdal in sociology classes; they discussed Nietzsche, Aristotle, Hegel in philosophy classes; they studied the black giants in compulsory Negro history class; many students read Facing Mount Kenya, Nkrumah and Basil Davidson as supplements to the Negro history class; they analyzed essays of Ruskin, Macaulay, Tom Paine in literature classes; they interpreted the poetry of Lord Byron, Shelley, Keats, Ferlinghetti and Gabriel; they discussed the matters of the day — the Vietnam War, the draft — with their colleagues: H. Rap Brown, Stokely, Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer, Malcolm X. It should not have been a baffling wonder to the administration and the faculty that Tuskegee Institute was producing critical thinkers in an age when critical decisions had to be made.

A separate peace permeated the campus as each component went about its respective business, stopping every now and then via meetings to see the other perspective. The campus buzzed with activity. The community buzzed with activity. There was order and mutual respect.

On January 3, 1966, a shot fired by a white gas station attendant pierced the peaceful still of the night. Sammy Younge, Jr., lay dead on the January-cold concrete. A student activist who challenged the “white-only” toilet was killed in the line of duty.

Tuskegee came unglued.

The campus was in perpetual turmoil for three years thereafter. The acquittal of Sammy’s murderer reopened the discussion of the students’ role in advancing equality in a racist society. The question was asked by students who painted a yellow stripe down the back of the confederate soldier in the downtown square and attributed the deed to “Black Power!” The questions kept being raised in more meetings and demonstrations; it was clear the students at Tuskegee Institute would no longer settle for answers that left them invisible.

Tags

Gwendolyn M. Patton

Gwen Patton is field director of the Southern Rainbow Education Project in Montgomery, Alabama and a member of the Working Group on Electoral Democracy. This fall, she plans to run as an Independent against U.S. Senator Richard Shelby. She talked with Bob Hall about who owns the government. (1992)