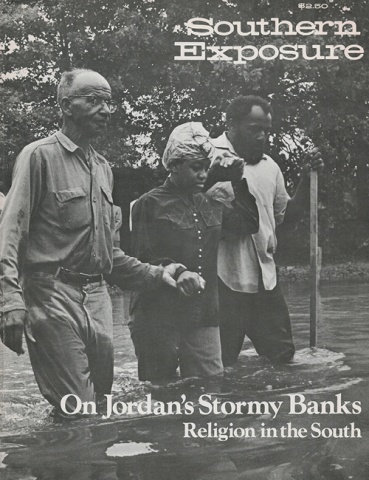

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Aiken, South Carolina, has a long tradition of combining strange cultural forces. Esteemed as a health resort by virtue of its dry, pine-scented air, by the late 1800s, it had become a winter season gathering place for the very rich. The W. R. Graces and the Ambrose Clarks, the Goodyears and the Vanderbilts maintained palatial “cottages” there. Every year they arrived with their stables of polo ponies and thoroughbred riding horses and train loads of servants to encamp for six weeks of gala partying, riding to hounds and competing with each other in horse shows before drifting on to Palm Beach or back to Long Island. Most of these “winter people” were Roman Catholic.

There was also a small and thriving population of local Catholics, black and white. I was one of these and my father, following a long tradition of Catholicism in his family, raised us as devout Catholics with, I believe, the best of intentions. The construction of the Savannah River nuclear power plant in 1950 deposited more Catholic Northerners in the town.

The Catholic community was large enough to support a parish church with the size and sweep of a small cathedral. St. Mary Help of Christians church was set on spacious grounds which it shared with a delicate chapel, a national wonder among church architects. St. Mary’s boasted Byzantine gilt ceilings, wooden pews with brass plates for family name cards, several large marble statues of saints and a formidable marble altar. The Monsignor of the parish, the son of a wealthy Northern family, rode to hounds with the winter people and was included in all their social events.

There were few poor Catholics. The very poor attended a smaller mission church in “the valley,” Horse Creek valley, a textile mill community not far from Aiken.

St. Mary’s parish supported a Catholic grade school and a high school attended by local Catholics and boarding students. The Dominican order of nuns who taught in the grade school lived in a winter resort home on some acreage.

Black Catholics rarely came to Mass at St. Mary’s church; none attended St. Mary’s school. St. Jerome’s church and school had been built especially for them and an order of black nuns taught there. I remember one time when a group of concerned white mothers held a hurried conference with the St. Mary’s principal because they had heard she was going to invite students from St. Jerome’s for a get-together. They never came.

I don’t think it crossed my mind then how curious it was for there to be an entirely separate group of black Catholics. We didn’t think about race: concern for racial equality paled beside our utter absorption in the church.

In those days, being Catholic in Aiken meant that I had few friends outside the church. Opportunities for interaction were few, and the mutual mistrust between “us” and “them,” between Catholic and Protestant, was deep. The mother of my best non-Catholic friend discouraged religious conversation between us and forbade her to go with me where there were more than two Catholics gathered together. Likewise, I did not attend activities sponsored by another church. My mother was Presbyterian but had signed papers before she married, vowing to raise her children as Catholics. Her religion prompted occasional, deep torment in me since I believed with a child’s devoutness that “outside the Catholic church there is no salvation.”

Our lives were further segregated from our peers because we spent so much time at church. We went to Mass every Friday and Sunday; during Lent, we went every day and were expected to receive Holy Communion. If we didn’t, a nun would take us aside after Mass and ask leading questions about the state of grace in our souls. The true test of friendship between girls (the only acceptable friendships) was the frequency with which you knelt together and received communion. We confessed frequently, starting at the age of seven.

Beginning in first grade, we studied our catechism fervently, first period every morning. It must have sounded odd to hear small children discussing transubstantiation and consubstantiation understanding the definition as well as the nuances of each term. Even now, I am amazed and somewhat frightened that I can reel off cathechism responses almost automatically though I haven’t been to church in years. The Dominican nuns were a teaching order and their zealous dogmatism was matched by their unflagging intellectual ism. When I entered public school in ninth grade, I was intellectually quicker but emotionally more infantile than my classmates. I was extremely naive, a perspective I carried through years of dirty jokes and to the bitter end of my first love affair. He was a Baptist and we separated, finally, when I balked, horrified, at his suggestion that we commit the serious sin of French kissing.

My sense of propriety was shared by my Catholic friends and in all of us it was balanced, fortunately, by our flair for the dramatic. We got this ability to intensify any situation, I believe, from years of being steeped in the exotic medieval rituals which punctuated the liturgical year.

Christmas Eve midnight Mass was the climax of the church year; St. Mary’s church really pulled out the stops at Christmas. The church glowed with hundreds of candles flickering against a background of fresh greens and banked poinsettias. The Knights of Columbus, a men’s fraternal order, formed a double line from the door of the church to the altar. Dressed in black capes and tall plumed hats, they drew their swords simultaneously to form a silver arch under which the Monsignor walked. Accompanying him were a dozen altar boys swinging decorative incense pots; one carried the gold chalice for communion on a purple velvet pillow.

Everyone, Catholic and Protestant, it seemed, came to midnight Mass for this amazing pageant. Many were drunk. People fainted and left suddenly, and the woozy smell of gin rose with the incense. It was also one of the few times I saw black Catholics at church.

I suppose the biggest, most obvious, difference between me and my non- Catholic contemporaries was the high visibility of our religious fervor. We wore school uniforms year round, miserable shirts, jumpers and skirts of a distasteful color approaching turquoise blue (the Virgin Mary’s color) and so flimsy that the winter wind cut right through. We wore medals of devotion to our patron saints around our necks or pinned to our identical gray sweaters. At the beginning of each Lenten season we could be seen with ashes marking our foreheads. We refused meat on Fridays. Girls went to extremes, shunning sleeveless shirts, low-cut shoes, pull-over sweaters or non-devotional jewelry as affronts to virgin modesty. Movies were checked against the approved list posted beside the confession booth. We murmured our prayers and sang long, atonal chants. We were noticeably subdued during the 40 days of Lent while we did penance and meditated on the crucifixion. I usually gave up ice cream and candy for Lent and ate candy and ice cream on Easter Sunday until I got sick.

If this had been my only life, I would by now be certifiably insane. But I had another life outside the church, a life just as extreme in its own way, which gave me valuable balance. I was deeply pious, but my time outside the church was spent running wild through the woods just behind my house. Every afternoon and weekend I would disappear into these woods, alone or with friends, and play great fantasy games with my herds of wild horses.

Tags

Pam Durban

Pam Durban is on the staff of The Patch in Atlanta, Georgia, and has written for the Great Speckled Bird and the Atlanta Gazette. She recently edited a collection of interviews and recipes called Cabbagetown Women, Cabbagetown Food. (1976)