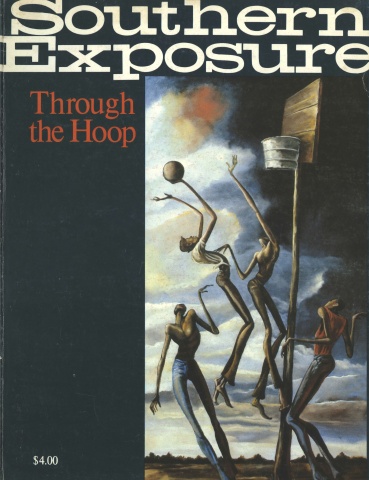

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

Behind a small frame house on a secondary road in the mountains of Appalachia stand 30 or 40 wire coops, each with a tin roof and a plastic milk-jug feeder. “Chickens,” comments the observant passer-by. Only the initiated know that the roosters are gamecocks and that their owner is a cocker, a participant in the ancient sport of cockfighting.

Known as the Sport of Kings, cockfighting is popular throughout the world, especially in Latin America, Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Each culture has its own set of rules, trappings and gambling structure, jargon, accoutrements and memorabilia.

Within the United States, cockers can be found in every corner of the country, even though cockfighting is prohibited in almost all states. But it is in the rural communities throughout the South, from Virginia to New Mexico, that the sport has its deepest and oldest roots.

One can get a glimpse into this world by reading one of the three major periodicals addressed to American cockers: Grit and Steel, The Feathered Warrior and The Gamecock. These magazines announce derbies, advertise game fowl and display the wealth of veterinary supplies and other paraphernalia on the market — gaffs priced at $50 to $60 a set, spurs, saws, scales, even belt buckles and automobile tags bearing pictures of cocks. In addition, each issue contains articles and columns with information and advice on all aspects of cockfighting. Titles of recent articles in Grit and Steel, for example, include “Histories of Gamecocks,” “Meet Our Young Cockers,” “Nutrition of the Gamecock,” and “How Gamefowl Has Helped My Life.”

Popular notion holds that cockfighters are cruel, barbarous and psychologically deviant. Recently, however, this belief has been refuted by Clifton Bryant of VPI and the late William C. Capel of Clemson University. Through the auspices of Grit and Steel, they distributed a questionnaire designed to obtain a variety of information on the psychology and sociology of cockfighting. Cockers, they found, are an amazingly diverse lot in terms of the standard demographic variables; there is no “typical cockfighter.”

More significantly, as a group cockers are not psychopathic but instead are psychologically similar in attitudes and personality patterns to others in their socio-economic groups.

An estimated half-million Americans have some contact with cockfighting each year. Many individuals go to a single fight out of curiosity or attend fights periodically for purposes of gambling. A few are professional gamecock breeders and fighters who ship gamefowl throughout the world and travel thousands of miles annually to attend fights at major pits. The majority, however, are hobbyists who maintain a relatively small number of roosters, perhaps 30 or 40, and fight them once or twice a month during the cockfighting season.

Even for these amateur cockers, the breeding and care of the gamefowl is a major concern. For thousands of years, gamefowl have been selectively bred for aggressiveness and fighting ability. In fact, some scientists claim that chickens were originally domesticated from wild jungle fowl for recreational use rather than for food production. By now there are many strains of gamefowl, such as Arkansas Travelers, Clarets, Madigan Greys, Butchers, Allen Roundheads and White Hackels. Southern cockers frequently interbreed two strains of gamecocks in search of a “gamer” rooster. A cock may, for example, be three-fourths Claret and one-fourth Madigan Grey.

Although breeders often do not maintain the purity of the strain, they make every effort to keep gamefowl reproductively separate from common domestic strains of chickens. They point out that “gameness” — the elusive quality of bravery that makes a cock continue fighting, even when seriously injured and dying — is of prime importance. If a cock fails to demonstrate this quality, especially if it runs in the pit, it is called a “dunghill,” meaning that it is part commercial chicken. Such behavior on the part of the cock is a source of embarrassment to the owner, and there are tales, though unsubstantiated, of the angry owner who wrung the neck of a cowardly cock.

There are several tasks involved in preparing a cock for fighting. If the rooster has never been fought, its comb and wattles must be “dubbed” (see photograph). The cock’s natural spurs, which may be several inches long, are also removed with a “spur saw,” a modified hack saw. A stump about one-half inch long is left to enable the artificial spur to be anchored firmly on the leg.

Some of the cock’s feathers are also removed prior to a fight, especially in hot weather. Typically, this “trimming out” includes shortening the long feathers of the tail and the wing primaries and removing some plumage from the saddle or back and around the vent. Trimming helps reduce overheating in the bird and, by lightening it, may enable it to fight against a lighter opponent.

When roosters are molting, or shedding feathers, during the late summer and early fall, they do not fight well, so no matches are held. But the long cockfighting season covers the rest of the year, lasting roughly from Thanksgiving to the Fourth of July.

During the two-week conditioning period prior to each fight, the cock is “put on a keep,” a regimen designed to get the bird in top fighting form. The keep usually involves limiting the cock’s water and giving it special exercises, such as throwing it up in the air to make its wings flap. Ordinarily a cocker has his own keep, which may be a complex and well-guarded secret, including special foods and vitamin supplements.

The most common type of organized cockfight in the United States today is the derby, in which a number of cockers, usually between 10 and 30, enter a pre-set number of roosters, usually four, five or six. Each cocker pays an entry fee, most often $50 or $100, which goes into the common pot. The cocks are fought round robin, and the cocker whose roosters win the most fights triumphs. This individual generally takes home the pot, although sometimes the pot is divided between the first- and second-place winners.

The derby is of relatively recent origin, probably dating from about 1929. It has been suggested that it emerged as the dominant form of cockfighting because it allowed an individual with a fairly small number of roosters to compete at least several times a year. Many older types of fights, in contrast, require each participant to enter far more cocks, with the result that in the past cocking was largely a rich man’s sport.

Cockpits in the United States vary from simple barns to portable pits that can be set up in the woods to elaborate, specially designed buildings with air conditioning, theatre seats, public address systems and snack bars. A typical pit in Southern Appalachia is located out of view of the road, with parking space for perhaps 50 or 100 cars. Surrounding the pit area are cockhouses, where the roosters are prepared before the fight. The pit usually has a bleacher capacity of 200 to 300 spectators, a refreshment stand, a booth for the score keepers and two pits. The “main pit,” where all fights are begun, has either fluorescent or incandescent bulbs for night fights and is the center of attention for most spectators. If it appears that the fight will be a long one or if others are waiting their turn to fight, the cocks are moved to a secondary or “drag pit,” so that a new match can get underway.

The pit owner charges spectators and cockers an admission fee, usually about $5. From this he must pay such expenses as the fees for the referees (as much as $100 per day plus expenses at major pits) and upkeep of the pits, including disposal of the dead birds. It is important that the pit owner maintain a good relationship with the local community, and he is often assisted in this effort by the regular participants. For example, at one pit in western North Carolina patrons periodically contribute to the upkeep of a nearby church.

At the pit, the cocker is assigned a room in a cockhouse where he places each cock in a separate compartment. After he has selected his “entry” of roosters, he fills out a “weight sheet” with the weight of each rooster and turns it in to the scorekeeper, who then seals a numbered metal band on the leg of each cock. Next, the scorekeeper matches up all the entries by weight, with each cock within two ounces of his opponent. The exception to this rule is that “shakes” — cocks weighing over six pounds — are matched regardless of exact weight. The scorekeeper then makes an announcement like this: “Numbers 2 and 14, pick up your weights.” In response, derby entrants number 2 and 14 pick up slips of paper from the scorekeeper telling which roosters they are to fight next. They then return to the cockhouse to “heel” the roosters specified.

This procedure, which takes 15 or 20 minutes, is quite intricate: the cocker ties the gaffs on the stubs of the rooster’s natural spurs with waxed string, so that they are firmly attached at the desired angle. Lest the cocker substitute a rooster for the one called, the referee reweighs each cock at the pit area and checks its numbered band.

The actual pit in which the fights are staged measures about 15 feet in diameter and is surrounded by a 1 three-foot-high fence. During the fight two handlers, the referee and two cocks are in the pit. The referee’s job is to tell the handlers when to fight the roosters, when to “handle” or pull them apart, and when to rest them. He also keeps “the count” and ensures that both handlers abide by the rules. The rules of cockfighting are quite complex and vary from pit to pit, but most fights follow a basic pattern.

The match begins with a procedure called “billing up.” In order to incite the roosters to attack, the “handlers” cradle them in their arms and allow them to peck at one another. With his foot or a stick the referee then draws two parallel “score lines” six to eight feet apart in the dirt or clay floor of the pit. The handlers place the roosters at their respective score lines and release them at the referee’s command, “Pit ’em!” The cocks then fight until the gaffs of one become entangled in the body of the other. The referee stops the pitting with the command, “Handle!” and the handlers disentangle the cocks. After a 20-second rest period, the cocks are again pitted. This procedure continues until there is a winner.

A fight ends in one of three ways: one of the cocks dies, one of the handlers concedes the fight, or a cock fails to attack for three successive pittings of 10 seconds and one pitting of 20 seconds. (This “count” is a good example of rule variation: in some pits a cock loses after only three 10-second counts.) The referee cannot initiate the count. When a cock stops pecking or spurring, whether because of injury, exhaustion or lack of gameness, the opposing handler says, “Count me.”

The referee then begins a count of 10 seconds. If the cock does not attack within the 10-second period, the other rooster is said to have the count.

Subsequent pittings are then initiated at the “short score” lines, which are two feet apart and increase the probability of attack. If the cock with the count against him attacks by a peck or a spur, even if it is not directed at the opponent, as in the case of a rooster that has been blinded, the referee calls, “Broke!” indicating that the count has been broken.

Although a fight averages about 10 minutes in length, it may be over in as little as 10 seconds, if a cock is killed in the first pitting, or it may last over an hour. The number of pittings is extremely variable also, ranging from one to over 100 but averaging about 20. Pitting length averages 15 seconds but varies from one second to over 60.

Cockfighting is a lethal sport. We asked several cockers to keep records on how often their roosters died during or soon after a fight. Only five percent of the winners died from injuries sustained in fights, they reported, whereas almost 80 percent of the losers died. Despite the violent nature of the sport, cockfighting is not as visibly gory as many suppose. There is little overt bloodshed. The puncture wounds made by artificial spurs do not bleed much externally, and the cock’s feathers tend to conceal bleeding. (As a result of breeding, the blood of a game rooster clots more quickly than a commercial chicken’s.)

Still, roosters “take a lot of steel,” meaning that they receive many wounds. An autopsy performed on one cock revealed that it had 18 holes in its body in addition to the fatal blow, which was to its throat so that it choked on its own blood. Common injuries are described with special terms. A rooster which has had its lungs punctured, for example, emits a low rasping sound as it breathes and is said to be “rattled.” A rooster which has sustained an injury to the spinal cord and is therefore unable to use its legs is said to be “uncoupled.”

Regardless of the length of a derby, the spectators are an active part of the scene. They arrive early — before six, for example, when a match is scheduled for 10 at night, and they await the outcome even when the fight runs on till four in the morning. A typical crowd in North Carolina may include both blacks and whites, men and women of all ages, perhaps mothers with infants. Although cockfighting is considered a man’s sport, Grit and Steel has one female cocker as a regular columnist; like many cockers, she acquired her interest through her family.

At least in rural communities, where cockfighting is not perceived as a serious violation of community standards, cockers appear not to feel threatened by local law enforcement agents. They make no attempt to conceal their involvement in the sport. In fact, they identify themselves by forming local clubs, and they eagerly exchange tales and information. Furthermore, spectators develop a sense of camaraderie with one another, and while waiting for a match to begin they sit around talking and joking. Some shoot craps or pitch pennies; others go outside the pit to drink beer.

Because of the presence of gambling, alcohol and sometimes weapons, cockfights are potentially violent situations. As a safeguard, therefore, pit operators often ban alcoholic beverages from the pit, and they maintain some degree of control over the fights. Consequently, serious disputes between cockers or against a referee’s decision are rare, and violence is far more frequent at informal neighborhood “brush fights” than at permanent pits.

Nevertheless, cockfighting is a colorful and rowdy affair. The action of the pitting is so fast as to seem blurred and almost choreographic as the cocks leap into the air, spur, peck and feint in a series of synchronized moves. The handlers develop a certain amount of showmanship, employing some ritualistic treatment to an injured cock, such as blowing into its mouth or wiping its face with water. Spectators are also caught up in the excitement and yell out advice, especially to novice cockers. Those close enough to hear “rattles” announce the fact and may change their bets. Should a cock turn and flee from its adversary, the spectators are quick to express their derision.

Gambling is an important part of the scene. In a derby the major amount of money to exchange hands is the pot, which is composed of the entry fees of all the participants. Since there may be 30 or 40 entrants in a large derby, each paying $50 or $100, this sum can be considerable. In addition, cockers usually make side bets on their own roosters, and spectators engage in betting throughout the fight. At some pits there may be a third form of gambling: a lottery based on the number arbitrarily given to each cocker when he pays his entry fee. Prior to the derby each number is auctioned off to the highest bidder. The money from the raffle goes into a separate pot, and the person who purchased the number of the winning cocker wins the lottery.

As soon as the cocks are brought into the pit area spectators begin to call out odds, which may be accepted by any other spectator. For example, a spectator may shout, “I’ll lay a 25-to-20 on the gray,” meaning that he is offering $25 against $20 that the grey cock will win. To accept the bet someone calls out, “You’re on” or “You and me.” The odds are often based more on the reputation of the handler than on the appearance of the cock; however, the odds can be shifted when a cock is noticeably superior or injured. Social pressure dictates that bets be paid off promptly and without malice. Some bets are paid off even before the referee has made his decision. And considering the informal nature of the gambling system, disputes over the payments of bets are surprisingly rare.

To the people involved in cockfighting, it is a traditional, dramatic and thoroughly legitimate sport. They point out that the behavior of a spectator at a Tennessee or South Carolina cockfight on a Saturday night is amazingly similar to that of a “Big Orange” or “Fighting Gamecocks” football fan on a Saturday afternoon. To the larger society, however, the legitimacy of cockfighting remains questionable. Should such an activity be suppressed? Should it be tolerated as a folkway which falls outside the law? Or should it in fact be legalized and supervised, as has been the case for countless other violent activities from spear fishing and turkey shoots to boxing and football?

In the states where cockfights are currently legal, there already exists a variety of restrictions. In Florida, for example, artificial gaffs, the hardened steel spurs attached to the stubs of the cock’s natural spurs, are illegal, and gambling is prohibited. In Kansas, cockfights are barred on Sunday. And on the national level, Congress enacted a law in 1976 forbidding the interstate transfer of dogs or chickens for the purpose of fighting. The effect of this law, which provides for fines up to $5,000 and one-year imprisonment for violators, remains to be seen.

Early in 1978, the night after a dramatic episode of Roots had exposed a huge national TV audience to the colorful customs of antebellum cockfighting, police arrested scores of North Carolina residents — businessmen and farm hands — at an illegal cockfight. Ironically, the raid was conducted not far from the spot where [the real] Chicken George, Alex Haley’s slave ancestor, once lived and raised fighting cocks.

Tags

Harold Herzog

Harold Herzog, an assistant professor of psychology at Mars Hill College, has studied the behavior of snakes, alligators and tropical bats, as well as gamecocks. (1979)

Pauline B. Cheek

Pauline B. Cheek is a Mars Hill-based freelance writer who describes herself “as wife of a college professor whose light reading includes the encyclopedia, mother of three children who raise questions like mushrooms in monsoon season, and a student who aspires to remain one through age 99.” (1979)