This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 2, "Sick for Justice: Health Care and Unhealthy Conditions." Find more from that issue here.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Southern clay eater, that convenient fool of travelers’ accounts, journalists’ sensations and physicians’ observations, resisted a bellyful of hardship which might have convinced a weaker creature to seek extinction. Confined for generations to the sandiest and most barren portions of the South’s soil, where they were said to feed upon cornmeal and hog meat, the clay eaters became legendary for ignorance, filth, laziness and immorality. Despised by blacks for their shiftlessness and lamented by whites as degenerate descendants of almost pure Anglo-Saxon stock, these “poor whites” nonetheless managed to fatten the pages and nourish the careers of those writers remembered today as local colorists. In Georgia Scenes, for example, the antebellum humorist Augustus Baldwin Longstreet offers the character “Ransy Sniffle.”

Now there happened to reside in the county, just alluded to, a little fellow, by the name of Ransy Sniffle: a sprout of Richmond, who, in his earlier days, had fed copiously upon red clay and blackberries. This diet had given to Ransy a complexion that a corpse would have disdained to own, and an abdominal rotundity that was quite unprepossessing. Long spells of the fever and ague, too, in Ransy’s youth, had conspired with clay and blackberries, to throw him quite out of the order of nature. His shoulders were fleshless and elevated; his arms, hands, fingers and feet, were lengthened out of all proportion to the rest of his frame. His joints were large, and his limbs small; as for flesh, he could not with propriety be said to have any.1

By the start of the twentieth century, long after the Georgia clay had swallowed Longstreet, Ransy Sniffle and his kin remained. They had survived, perhaps had even been oblivious to the War, Reconstruction, Redemption and the collapse of agrarian revolt. These were mere trials for what lay ahead. For they had never met so meddlesome or so persistent an invader as ‘‘The Uplift.” Nor did the schoolhouse of Progress allow truants.

One day in 1908, Ransy Sniffle propped himself against the stationhouse wall of a small railroad town somewhere in the South. In the smoking car of a passing train, three members of President Theodore Roosevelt’s Commission on Country Life sat speculating upon what one of them called ‘‘this land of forgotten men and forgotten women.” Henry Wallace, an Iowan unacquainted with crackers and sandhillers, noticed Ransy first. ‘‘What on earth is that?”

‘‘That,” said Walter Page, journalist and social reformer, ‘‘is a so-called ‘poor white.’”

‘‘If he represents Southern farm labor,” Wallace replied, “the South is in poor luck.”

Then, Dr. C. W. Stiles startled both Page and Wallace. “That man is a dirteater. His condition is due to hookworm infection; he can be cured at a cost of about fifty cents for drugs, and in a few weeks’ time he can be turned into a useful man.

“The hookworm,” Dr. Stiles explained, “is a parasite picked up in larval form by barefooted Southerners, particularly children. Boring through the skin en route to the bloodstream, hookworm larvae produce symptoms known as ‘ground itch’or ‘dew poison.’ Carried by the blood to the lungs, they are coughed into the throat, swallowed, then move through the stom- ach toward the small intestines. There the worms attach their mouths to the intestinal membrane, feed upon their hosts’ blood and grow to full size — about one third of an inch long. Mature hookworms lay eggs which pass into human feces; they hatch and thrive in portions of the American South as well as in a number of subtropical countries where there is a combination of warm temperatures, frequent rainfall and sandy soil. A microscopic examination can detect the presence of hookworm eggs in human specimens and a dose or two of thymol and epsom salts provides a quick cure.

“Bad habits of human waste disposal (‘soil pollution’),’’ Stiles continued, “have led to the infection of as many as two million Southerners, most of them poor whites. Severe sickness (by five hundred or more worms) produces acute anemia and occasional death. Less severe infection weakens the victims and leaves them susceptible to other illnesses such as pneumonia and tuberculosis. Most commonly, the disease goes unrecognized and its victims feel continually weak.”2

Within weeks after this train ride revelation, Walter Page arranged for Stiles to tell his hookworm story to Frederick Gates, a former Baptist minister who was now the chief adviser in the philanthropies of John D. Rockefeller. Within months, the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease was formed with one million dollars of Rockefeller money promised for five years’ work.3 So began, in 1909, a campaign to transform Ransy Sniffle into a full-bodied participant in an industrializing New South.

The hookworm campaign was sustained by the myths of its time and was conducted by a complex company of interdependent characters. In part, it is a tale of hookworm determinism as a theory of history seriously proposed by a zoological specialist and eagerly accepted by regional boosters. It is also a story about the conception of human potential and the aims of philanthropy as understood by the royal family of American capitalism. And, despite its entanglements with the bugbears of racism and “the civilizing process,” it is a story of the emergence of widespread public health work in the Southern states.

“Germ of Laziness Found”

The son of a New York Methodist minister, Charles Stiles spent his life as a sanitation missionary. In 1886, at age eighteen, he began the study of medical zoology, seeking instruction at universities in Berlin, Leipzig, Trieste and Paris. Investigating internal parasites, young Stiles made the acquaintance of Ancylostoma duodenale, the Old World hookworm known in Italy and Switzerland since the mid-nineteenth century as a cause of severe anemia among tunnel workers, brickmakers and miners.4

Stiles determined from temperature, climatic and soil conditions that the New World probably had its share of hookworm disease, yet when he returned to the United States in 1891 to work as a zoologist for the Bureau of Animal Industry, he found no sample of human hookworm in the Bureau’s collection. It was not until 1901, when Stiles examined samples of hookworms sent from Puerto Rico and from Texas, that he discovered the new species which he named Necator americanus, the “American murderer.” A few years later, when Dr. Arthur Looss found N. americanus among African natives, it became evident that this species had actually come to America as a baggage of the slave trade.5

In 1902, Stiles maneuvered himself from the Department of Agriculture into the US Public Health Service and undertook a Southern survey trip to explore the distribution of hookworm. Sampling his way southward from Washington with as yet a vague notion of the parasite’s favorite soil, Stiles also encountered the resistance of miners and brickyard workers to a Yankee doctor who wanted “specimens.” By the time he reached the sandy lands of South Carolina, Stiles had uncovered only a few cases. Finally, in Lancaster County, he “found a family of 11 members, one of whom was an alleged ‘dirt-eater.’ The instant I saw these 11 persons I recalled Little’s (1845) description of the dirt-eaters of Florida....A specimen from one of the children gave the positive diagnosis of infection.”

Continuing through Georgia and into Florida, Dr. Stiles found dozens of infected farm families and factory workers. He also discovered that the disease showed more severe symptoms among whites than blacks. During this three month excursion, Stiles discussed his findings with a Southern medical society and conducted several small clinics, demonstrating the hookworm cure to local physicians.6

Inspired, one Atlanta doctor, H. F. Harris, made his own field trip through Georgia and into Florida. Harris was

. . . much astonished to find that this disease affected a large percentage of the population in many districts, the unfortunate sufferers being generally regarded as dirt-eaters .... I discovered the fact that almost all instances of profound anemia were due to the uncinaria [hookworm], and not, as has been heretofore generally assumed, to the malarial parasite.7

Other Southern doctors were soon making similar discoveries.

In December, 1902, Stiles summarized his Southern trip before an annual meeting of the Pan-American Sanitary Conference in Washington, DC. The New York Sun gave his comments front page treatment under the headline “GERM OF LAZINESS FOUND? DISEASE OF THE ‘CRACKER’ AND OF SOME NATIONS IDENTIFIED.” According to the Sun, Stiles declared that the presence of hookworm in the South had caused “the pitiable condition of the poor whites. Its presence in succeeding generations had resulted in their inferior physical development and mental powers and is the cause of the proverbial laziness of the ‘cracker.’ ” Stiles added that, “Attention paid to this matter by planters and farmers in the Southern States would result in not only improved conditions generally, but a great increase of the percentage of work which they would secure from their employees.”

Continuing, Stiles made another assertion, one which would bring him criticism from members of the child labor movement. Because stunted disease, and because he had discovered several hookworm-infected mill workers as old as twenty-eight who looked only half their age, Stiles concluded that child labor reformers were generally deceived regarding the ages of factory hands.8 In fact, a Census Bureau study of 1900 had shown that three out of ten workers in Southern mills were children under sixteen and 57.5 percent of these children were between ten and thirteen years of age. And although their wages were much lower, the children’s eleven and twelve hour days were no shorter than those worked by their parents.9

Across America, newspapers and magazines picked up the Sun’s story of Stiles’ discoveries and while humorists took aim once again on Ransy Sniffle, that tired caricature with many names, other writers sighed, "How much of the South’s past does Stiles’ theory explain! How much for the South’s future does it promise.”

Years later, reflecting on the Sun article, Dr. Stiles wrote that it had been “an exceedingly valuable piece of work in disseminating knowledge concerning hookworm disease.” In praise of the newspaper’s use of the “germ of laziness” expression, he noted, "It would have taken scientific authors years of hard work to direct as much attention to this subject.”10

During the years after 1902 until the meeting with Page and Wallace in 1908, Dr. Stiles worked single-mindedly for his cause. Filled with the zeal of turn-of-the-century reformism, he combined valuable insights of preventive technique with the changing etiquette of modern life:

My hobby may be summarized in the two words: “Clean Up.” In our filthy American habits of daily life, I see the cause of more preventable sickness and preventable death than I do in any other one factor. . . . Think of it my friends, that despite the agitation on the subject of tuberculosis, we Americans have not yet shown the moral courage to stop that filthy and pre-eminently American habit of promiscuous spitting, and think of it, that 55% of the American farm homes of which I have record have no privy, but are permitting a continuation of the Andersonville stockade soil pollution.11

At medical schools and at state medical conventions Stiles presented papers, offered demonstrations and exhibited hookworm patients. In 1903 he wrote a bulletin for the Public Health Service’s Hygienic Laboratory which included a discussion of sanitary privies. At first denied publication on the grounds that such a topic was too disgusting for a scientific paper, Stiles eventually saw his pamphlet printed; 350,000 copies of another Stiles bulletin on privies and the safe disposal of “night soil” were distributed free by the US Department of Agriculture. These pamphlets continued to present his “conservative view” of the economic significance of hookworm disease "as one of the most important factors in the inferior mental, physical, and financial conditions of the poorer classes of the white population of the rural sand and piney wood districts. Remove the disease and they can develop ambition.”

Stiles’ lobbying in behalf of Southern sanitation gained little for him in Washington except the nickname of “Privy Councillor.” As yet unwilling to underwrite an intensive government campaign, administrative officers in the Treasury Department apparently squelched the request of South Carolina Senator Ben “Pitchfork” Tillman for a $25,000 hookworm appropriation. Determined, Stiles continued in solitary fashion.12

The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Southerners were living amidst overwhelming poverty. The post-War emergence of the crop lien system had developed into sharecropping, a new sort of slavery with both white and black victims. The rise of textile mills — that great hope for which New South boosters of the 1880s and ’90s offered investors low taxes, free land and unorganized labor — was creating a growing population of wage slaves. Native ores, minerals and timber were being hauled away as fast as Northern owners (Mellons, Morgans, DuPonts and Rockefellers) could lay tracks to their mines, mills, forests and wellheads. “The advance of industry into this region,” concluded geographer Rupert Vance in 1932, “then partakes of the nature, let us say it in all kindliness, of exploiting the natural resources and labor supply of a colonial economy.”13

From the point of view of Yankee philanthropists who began to tour the South annually in 1901 aboard special trains organized by New York merchant-churchman Robert Ogden, widespread poverty and backwardness were drags upon Progress. Soon these Northern men of money and their Southern agents began a series of campaigns, each aimed at a specific deficiency, which combined humanitarianism with the aggressive attitudes, efficient methods and narrow-minded goals of modern business.

The first of these large-scale organizations for Southern do-good was the General Education Board. Between 1902 and 1909, the John D. Rockefellers — Senior and Junior — placed $53 million into the GEB, underwriting a survey of rural education conditions, promoting state school building campaigns and paying the salaries of several professors of secondary education at state universities. Turning to agriculture, the GEB supplied money for the work of Seaman A. Knapp, the developer of demonstration farming. With its director, Baptist minister Wallace Buttrick, as a plump example, the General Education Board learned to spawn effective South-wide campaigns by drawing its leaders from the region’s college presidents, ministers and editors.14

These “estimable gentlemen with high collars and fine principles,” C. Vann Woodward has written, “were very much in earnest, but the changes they envisioned included no basic alteration of social, racial, and economic arrangements.”15

One of these philanthropic professionals was expatriate Southerner Walter Page who, as a member of various boards, governmental commissions and private coteries, energetically pursued the redemption of the South from his bases in Boston and New York. Page’s 1897 address, “The Forgotten Man,” sounded a call of rescue for poor whites and blacks, and signaled a shift in the emphasis of the Uplift from mill construction to education. By 1908 Page was ripe for the discovery of that most forgotten of men, Ransy Sniffle, and for Dr. Stiles’ hookworm evangelism. It was Page who put Stiles in touch with GEB secretary Buttrick. An all-night conversation with Dr. Stiles convinced Buttrick to arrange a further meeting, this time with Frederick Gates — the chief steward of Rockefeller philanthropy.16

After long discussion over the details of staff and operations, the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease was organized on October 26, 1909, with a pledge of one million dollars for five years’ work. Drawn primarily from the trustees of other Rockefeller philanthropies (ranging from the GEB to the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research), the Sanitary Commission board of directors consisted of twelve men: Page, Stiles, Gates, Rockefeller Junior, Starr Murphy, P. P. Claxton, David Houston, J. Y. Joyner, H. B. Frissell, E. A. Aiderman, William Welch and Simon Flexner.17

Wickliffe Rose, Tennessee native, philosopher and secretary of the Peabody Fund, was chosen as administrative secretary at a salary of $7,500 plus expenses. Sensitive of the Southern temperament regarding Yankee invasions of any sort, Rose’s first act was to rent an office for the Sanitary Commission, not in New York but in Washington. Already a chorus of outraged Dixie newspapers were protesting. “Where was this hookworm or lazy disease,” asked the Macon, Georgia, Telegraph, “when it took five Yankee soldiers to whip one Southerner?” A North Carolinian suggested the campaign was just another Rockefeller scheme to make more money by going into the shoe business.19

“We have had to overcome”

In their seven years of Southern experience prior to the hookworm crusade, the Rockefeller advisors had learned that success depended upon acquiring state and local government support for their projects. As Wallace Buttrick explained it in a 1925 speech to the New England Society, the philanthropists wanted to be thought of as “partners not patrons,” functioning in the background while the day-to-day responsibility was in the hands of cooperative state authorities.20

To conquer the hookworms, the Sanitary Commission set three tasks: determining the geographic distribution and estimating the degree of infection; curing the infected; and stopping “soil pollution.” Before entering any state, the Commission would wait for an invitation from that state’s board of health. A physician would be hired (as recommended by the state board and approved by the Commission) to act as state director. Then a field force of sanitary inspectors, a handful for each state, would be nominated by the state director and approved by the state board of health and the Commission. By November 1, 1910, state directors had been appointed and work begun in Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, South Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana. Kentucky and Texas were added in 1912. Florida started its own campaign before the Commission was organized, financing it through public health taxation.21

Wickliffe Rose proved a tactful and industrious administrator, corresponding continuously with public health officials, organizing meetings of the state campaign directors, traveling through the South to confer with boards of health. He continued to be particularly cautious in any matters which might arouse regional prejudice. Responding to an invitation by Walter Page to speak to the Round Table, a New York club whose members came from the intellectual community around Columbia University, Rose wrote in October of 1910:

I too meant to speak to you about the talk before the Round Table. I wanted to ask you first if you wanted me to tell about our work in the Southern States, and second, whether this could be done without its getting into the papers. Now that I see the program is to be printed and sent out I wish you would have called this off in the proper way. You know how sensitive our people are about having any man go to New York and talk about things that are being done in the Southern states. You know how much opposition was created by the press of the South by the publicity given to this work in the beginning. We have had to overcome. Everything is now going our way; all opposition is disappearing. I would not for the world do anything to interfere with the complete success of this work. For the present it is extremely important that the talking and writing be done in the South from the State Boards of Health.

Rose suggested that the topic of his talk be “Conservation of Country Life” for “this would be delightfully indefinite, at least, and would give a man oppor- tunity to say practically anything he pleases.”22

Expert in matters of propaganda, Rose regularly gave advice to his state directors. Enclosing a copy of the Commission’s first annual report, he suggested to Virginia’s Dr. A. W. Freeman how to use it for best publicity purposes.

It seems to me important that any publicity given it should be given through the medium of one or two of the leading papers in each of the states. If the paper which you select should notice it first, the chances are that any notice given it would be favorable. 23

Arkansas, the only Southern state having no public health budget in 1910, was completely dependent on Rockefeller money. Nonetheless, Rose wrote to the Commission’s Arkansas office,

I beg to advise you that your office be styled, office of the Arkansas State Board of Health. I should think it might be well to omit all reference to the Rockefeller Commission. It is our desire that everything be done so as to attract attention toward the State Board of Health and to create interest in its development. 24

Despite the efforts of Rose, Arkansas proved a troublesome state. When its legislature passed a public health bill in 1911, the bill was stolen before it reached the governor. A copy of the bill was prepared and signed, only to be declared invalid by the state attorney general. Frustrated, Arkansas hookworm campaign director Morgan Smith wrote to Rose:

You cannot have the slightest conception of the feeling engendered by this Bill, and so acrimonious have been the discussions and so intensely strained the relations of those who stand for right and those who represented the pernicious interests, that personal conflicts were hard to avoid The National League for Medical Freedom fathered the opposition and no doubt furnished the money. That the bill was stolen and somebody received money for doing the work is so strongly fixed in my mind.25

While Rose guided the administrative affairs, Dr. Stiles was traveling throughout the South, presenting technical as well as popular addresses to a variety of audiences and occasionally assisting in clinics. He was the leading presence at. the first Southern conference on hookworm, held in Atlanta on January 18 and 19, 1910. This event brought together doctors from throughout the region and its proceedings were given extensive coverage in four issues of the Journal of the American Medical Association.26 At the request of Rose, Stiles wrote a Public Health Service bulletin on hookworm symptoms and treatment for distribution to physicians.27 He met with a textile mill owner in an effort to get more privies built in mill villages. He conducted a personal sanitation survey (1910) of nearly five thousand farm homes in six Southern states which revealed that thirty-five percent of the white homes and seventy-seven percent of the homes occupied by blacks had no privies.28

In an address given at Hampton Institute in 1909, Stiles explored the implications of the less severe effects of hookworm disease on blacks as compared with whites, an observation he had first made in 1902. He speculated that “the negro race had this disease for so many generations in Africa that it has become somewhat accustomed to it.” With their “relative immunity” from the most debilitating effects of hookworm disease and with their higher incidence of soil pollution due to their greater lack of privies, blacks, said Stiles, became ideal spreaders of the disease. “The white man owes it to his own race that he lend a helping hand to improve the sanitary surroundings of the negro.”29

Stiles’ observations on black sanitary improvement came at a time of deteriorating race relations throughout the US.30 Many newspapers and periodicals injected their own interpretations and the code words of racism into Dr. Stiles’ remarks. In an article for McClure's Magazine entitled “The Vampire of the South,” Marion Hamilton Carter wrote:

Negro crimes of violence number dozens where his sanitary sins number tens of thousands. For one crime a mob will gather in an hour to lynch him: he may spread the hookworm and typhoid from end to end of a state without rebuke. 31

Perhaps the most extreme connection of black “sanitary sins” with the plight of poor whites and the mechanistic vision of progress appeared in Dr. Charles Nesbitt’s “The Health Menace of Alien Races,” an article published in The World's Work, a popular magazine founded by Walter Page.

In 1902, Dr. Stiles discovered that the hookworms, so common in Africa, which were carried in the American Negroes’ intestines with relatively slight discomfort, were almost entirely responsible for the terrible plight of the Southern white. It is impossible to estimate the damage that has been done to the white people of the South by the diseases brought by this alien race. Physical inefficiency and mental inertia are its results. Every enterprise that locates in the South today, if it uses the available white labor of the South, must reckon on not more than 40 to 60 percent of normal efficiency. As this phase of the race problem continues to be studied, it is inevitable that further investigation will produce still stronger evidence that the races cannot live together without a damage great to both; so great, that even now the ultimate extinction of the Negro in the United States is looked upon by many as assured. We also know that as his extinction progresses it is carrying tremendous damage to the white race.32

The Clay Eaters

If Ransy Sniffle’s lot in life could be conveniently traced to black health criminals, many of his favorite eating habits (which offended genteel propriety) were certain to be the result of hookworm infection. Frances Bjorkman was not the only journalist who, after traveling in the land of crackers, sandhillers, barrenites, pinelanders and shadbellies, concluded that “dirteating, alcoholism, snuff-dipping, incessant tobacco chewing — together with many other common perversions of appetite, such as resin-chewing, coffee chewing, and a morbid craving for pickles and lemons — had their origin in the derangement of the digestive tract caused by hookworms.”33

Nor could any Southern schoolchild have failed to know the hookworm catechism as written by Dr. Stiles and distributed by the tens of thousands.

Question 40. What is a dirt-eater?

A dirt-eater is a person who has an unnatural appetite, and on this account eats clay, sand, plaster, soot, wood, cloth, or other things not intended for food.

Question 41. is dirt-eating the cause of hookworm disease?

It is the result of the disease, not the cause.

Question 42. Can dirt-eating be cured?

Yes, very easily; by curing hookworm disease.34

Yet, despite the crusaders’ certainty, today the dirt-eating question remains unresolved. A review of recent scientific studies of pica, the desire to ingest and the ingestion of substances usually considered inedible, leads to several limited conclusions. Iron deficiency anemia of the sort caused by hookworm disease is common where pica is severe, but iron deficiency hasn’t been conclusively shown to be a cause of pica. Pica can be one of many symptoms of distressed, brain-damaged, or retarded children; it can occur in normally intelligent children under various sorts of stress.35

The cultural perspective on pica may be even more suggestive. Historian Robert Twyman takes note of a Mississippi study which shows that clay eating continues in the modern South. He interprets the practice as essentially a social habit handed down in the manner of a folk tradition. Not necessarily arising from an insufficient diet or a vitamin or mineral deficiency, clay eating, says Twyman, is presently practiced at all ages, by both sexes, and without regard to race. Disagreeing with Stiles, he believes that “no hard evidence has ever been produced that hookworm causes clay eating.”36

Treating the Infected

The preliminary Sanitary Commission survey showed heavy hookworm infection (forty to eighty percent of the population) along the sandy coastal plain through eastern Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and the southern parts of Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Heavy infection in Louisiana was found near the extended Florida state line and in the northern hills. Southern Arkansas and western Tennessee were also heavily infected, even to the Cumberland Mountain plateau.37

In 1910 and 1911 the Sanitary Commission put much effort into enlisting the South’s 20,000 physicians into “a permanent working force.” It published and distributed special bulletins on the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. State directors made personal appeals by letter to each of these doctors. Field workers gave lectures and demonstrations to medical societies and made many visits to practitioners.

So as not to compete with Southern physicians, field workers, upon making a positive microscopic diagnosis, would not administer hookworm treatment themselves but would send the patients to private doctors. Despite the many tactics of courtship however, the Commission’s efforts with local physicians proved disappointing. Not atypical of doctors’ reaction was that of Dr. J. C. Bramlet of Georgia who complained that the hookworm campaign was “an imposition on my professional rights . . . and a humbug, cheat, and an imposition on the people.”38

It was soon obvious that a more effective treatment program had to be developed. Many of the people most in need of cure were least able to pay for it. Florida, acting on its own through its public health fund, paid doctors three dollars a case for all cases cured. Some physicians in a few counties of Virginia and North Carolina agreed to give free prescriptions for treatment among the poor; women’s associations in these counties supplied the medicine.39

In December, 1910, a major innovation appeared in Marion County, Mississippi, as the South’s first free dispensary was opened. Funds were appropriated by the county and local physicians provided treatment. Years later, Dr. John Cully, organizer of this dispensary, recalled how he won his appropriation from the Marion County board of supervisors.

They were not at all inclined to offer any assistance in this work but I had asked for an appropriation of $300 with which to buy thymol and to fit up the little clinic in the office building of Dr. Simmons. (I might add that Dr. Simmons very kindly gave the space to us free of charge.) When the board refused to make the appropriation, I went out and collected specimens of feces from the sons of the members of the board. I placed these specimens in warm containers until the larvae hatched. I then placed these larvae under the microscope which I had set up in the court house and asked each member of the board to look through the microscope. When I assured them that their children were infested with these parasites, they immediately made the donation. I believe the records show that I treated three thousand cases free of charge.40

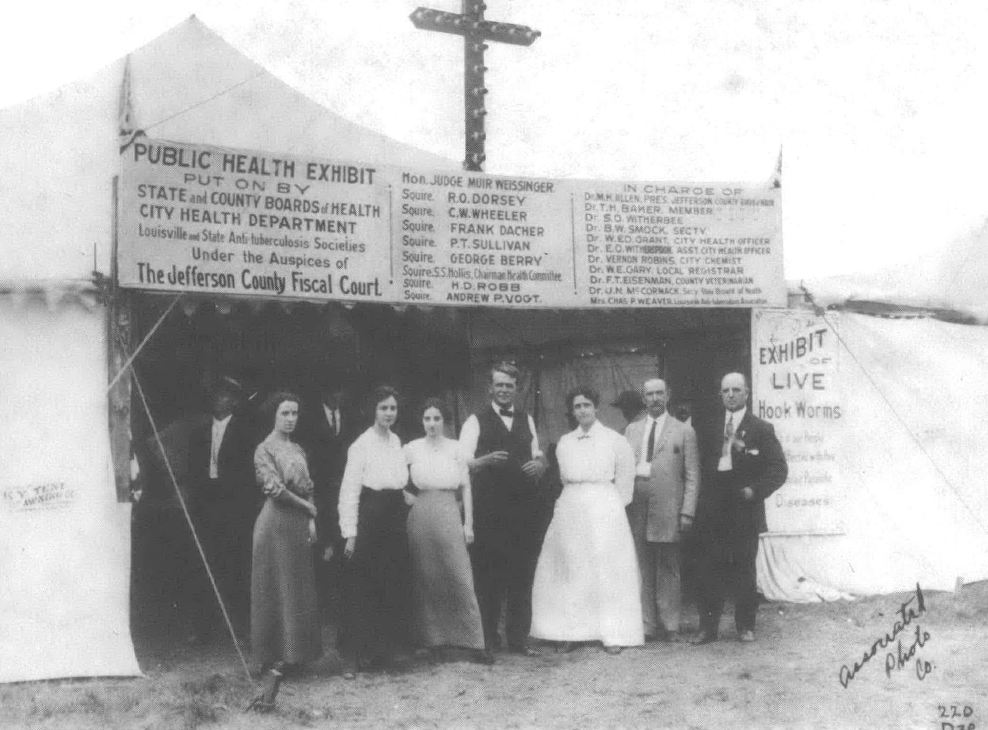

With the spread of dispensaries, the hookworm campaign was adopted into the Southern folk tradition of medicine shows, political rallies, and camp meetings. Typically, a fieldworker would secure a token appropriation from the county government, rally local women’s groups and civic organizations, then announce the coming clinic in the newspapers, by handbills, and with posters. On the appointed days, people would arrive early in the morning, walking or riding on wagons from miles away. They would swap hookworm humor, look at exhibits and slides, receive their examination and treatment, then return home to tell their neighbors. Blacks as well as whites were treated.

Operating at the county level with dispensaries open one day a week at several locations, hundreds of people could be seen each day for six to eight weeks. In the first year of dispensary work, 1911, 74,000 persons were treated in sixty-six counties of nine states. The next year, 150,000 persons in eleven states received dispensary doses of thymol and salts.41

State boards of education and schoolteachers were perhaps the Commission’s most effective allies. By 1915, instruction on the subjects of hookworm disease and soil pollution was made a part of school courses in eight states. Teachers attended summer institutes, organized lectures and slide shows, and built schoolhouse privies. Fieldworkers used local schoolrooms to set up demonstrations and organize the communities.42 Years later, South Carolina field director Dr. Francis Bell, remembered the special effectiveness of children:

In those early days of the fight against hookworm and soil pollution, it was difficult to get an audience of adults to attend a lecture concerning health matters, but the children attended in full force. These young people would carry the message home to the older ones, who would later question me on matters pertaining to sanitation. In this way, I taught the doubting adults thru the children.43

The building of sanitary privies did not keep pace with the treatment of the infected. Wickliffe Rose acknowledged in 1912 that “such rapid change in ingrained habit has not been expected.”44 A continuing sanitary survey showed that half of the 250,000 rural houses inspected in 653 Southern counties were without privies of even the most primitive sort in 1915. By means of extensive publicity, the Commission encouraged the building of privies but other than for demonstration purposes, it spent no money on construction.45

As public support for the hookworm crusade increased, so did the variety of techniques used to obtain local results. The Hattiesburg, Mississippi, Tribune printed a weekly list of the heads of families who had brought their privies up to snuff. “Hookworm Picnic Proves Success” was the title of a Mobile Register article which told of a public education meeting whose 700 participants heard a lecture by the state director, saw a series of “before and after thymol” lantern slides, and then broke out their basket lunches.46

The Hookworm and Civilization

Under the influence of the Sanitary Commission, the organizations and expenditures of state and county health departments grew rapidly. Especially active hookworm fieldworkers were sometimes invited to stay on as full-time county health officers.47 The need for health statistics and laboratory testing resulted in the development of other state-supported services. In 1914 the eleven Southern states reported spending $392,364 of their own funds for health departments as compared with $216,195 in 1910 — an eighty-one percent increase. Between 1910 and 1920, legislative appropriations for public health in the South increased more than 500 percent.48

Swept away by the accounts of the hookworm crusade as reported in dozens of small-town newspapers and by the field photographs in the Sanitary Commission’s files which showed countless sick made well, Walter Page was lost in tides of rhetoric. In a World's Work article entitled “The Hookworm and Civilization” (1912), he proclaimed that Dr. Stiles’ discovery of the hookworm was “the most helpful event in the history of our Southern states.” This parasite, said Page, “has probably played a larger part in our Southern history than slavery or wars or any political dogma or economic creed.”

Surely now, Page felt, with the removal of the main cause of Southern backwardness, Ransy Sniffle would stir with “red bloodied life.” “Every man who knows the people of the Southern states sees in the results of this work a new epoch in their history and because of its sanitary suggestiveness, a new epoch in our national history.”

Envisioning a South restored to the nation and to the grandeur it deserved, Page then moved on to the international scene. After making over the South, the Rockefeller hookworm campaign offered hope for “the re-making of tropical and semi-tropical peoples and the bringing of their lands into the use of civilization as fast as their products are needed.”49 Here was an ambition worthy of a Rockefeller.

As early as 1910, Frederick Gates had asked the Sanitary Commission to collect data on world hookworm infection. In 1913, with Gates’ approval, Wickliffe Rose presented a proposal at a trustees’ meeting which would use the patterns and methods of the Southern campaign to treat hookworm on a global scale. The International Health Commission was created in June of the same year with Rose as its director.50 Dr. Stiles, recalling the events of the last year of the Sanitary Commission, remembered Frederick Gates as a man “who always had his telescope focused on all corners of the earth.” Stiles felt that the Southern work was not finished. Gates, however, thought the time had come for the Southern states’ boards of health to assume the full load of work which had been carried on in their names. “As a result,” Stiles writes, “the Commission ended its days.” While Page, Rose, Gates and the Rockefellers moved on to pursue the planetary hookworm, Dr. Stiles retired to his laboratory and to his own variety of internationalism, the writing of a book on world parasitic diseases.51

In its final report, the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease calculated that its workers had examined a total of 1,300,000 persons in 596 of the South’s 1,142 counties. Of those examined, 700,000 had been treated. The average costs of each treatment had been $1.15 for the Commission and $.13 for counties. Perhaps as many as three million infected people were not yet reached.52

The original goal of eradication had not been accomplished, yet, in his letter of August 12, 1914, which announced the end of the five-year period for which he had pledged, John D. Rockefeller declared that he was satisfied. By having brought about a general knowledge among Southerners of the prevalence of hookworm disease and of the means of treating and preventing it, “the chief purpose of the Commission may thus be deemed to have been accomplised.”53 Through the International Health Commission, the Rockefeller Foundation continued to fund fifty percent of Southern state and county health costs until 1917, rapidly reducing their support thereafter.54

A modern South has not yet seen the eradication of hookworm disease. It remains, though infrequently, in the coastal plains areas from North Carolina to Mississippi. Like malaria, typhoid and yellow fever, hookworm disease disappeared with the modernizing of the South.55 Like pellagra, another Southern plague of the early twentieth century, hookworm took its heaviest toll among the poorest and most malnourished people. New diseases, representative of Southern changes, replaced the old. Ransy Sniffle, cured of his intestinal parasites and forced from the farm to the mill village, found newly built privies, but he also found a workplace that mated him with machinery, filled his head with noise and his lungs with fiber dust. Glad to be worm-free, he stood amidst the busy looms and shuttles, imagining only rarely the taste of blackberries and clay.

Notes

1. Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, Georgia Scenes (Augusta: S. R. Sentinel Office. 1835), p. 55.

2. Mark Sullivan, “An Emancipation," Our Times: The United States 1900-1925, Vol. Ill, Pre-War America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1930), pp. 319-323. Charles W. Stiles, Hookworm Disease in its Relation to the Negro, Reprint 36 from Public Health Reports, XXIV, 31 (Washington: US Public Health and Marine Hospital Service, 1909), pp. 3-7. Greer Williams, “The Hookworm Doctors,” in The Plague Killers (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969), pp. 7, 19-22.

3. Charles W. Stiles, “Early History, in Part Esoteric, of the Hookworm (Uncinariasis) Campaign in Our Southern United States,” The Journal of Parasitology, XXV (August, 1939), p. 300. Mary Boccaccio, “Ground Itch and Dew Poison: The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission 1909-1914,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, XXVII (January, 1972), p. 81.

4. Williams, p. 4. Sullivan, pp. 299-303. Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, Hookworm infection in Foreign Countries (Washington, DC: Rockefeller Sanitary Commission [hereafter RSC], 1911), pp. 77-85. Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1917 (Washington, DC: Rockefeller Foundation), p. 81.

5. Stiles, “Early History of the Hookworm Campaign,” pp. 288-289, 291-294. Williams, pp. 10-13. 6. Charles W. Stiles, Report on the Prevalence and Geographic Distribution of Hookworm in the United States, Hygienic Laboratory Bulletin No. 10 (Washington: US Public Health and Marine Hospital Service, 1903), pp. 37-53. Stiles, “Early History of the Hookworm Campaign,” p. 296.

7. H. F. Harris, “Uncinariasis: Its Frequency and Importance in the Southern States,” Transactions of the Medical Association of Georgia, 1903 (Atlanta: C. Baniston, 1904), p. 352.

8. New York Sun, December 5, 1902, p. 1. Boccaccio, p. 34.

9. Study quoted in C. Vann Woodward, Origins of the New South 1877-1913, Vol. IX of A History of the South (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1951), pp. 416-417.

10. Stiles, “Early History of the Hookworm Campaign,” p. 296. Sullivan, pp. 290- 299,323.

11. Charles W. Stiles, “Some Recent Investigations into the Prevalence of Hookworm Among Children,” Child Conference for Research and Welfare, Proceedings, Vol. II (New York: G. E. Stechert and Company, 1910), pp. 211-215.

12. Stiles, “Early History of the Hookworm Campaign,” pp. 296-298. Stiles, “Report on the Prevalence and Geographic Distribution of Hookworm,” pp. 50-54, 97.

13. Rupert Vance, Human Geography of the South (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1932), pp. 467-481. See especially Woodward’s chapter “The Colonial Economy” in Origins of the New South, pp. 291-320.

14. Raymond B. Fosdick, The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation (New York: Harper, 1952), pp. 8-9; Allan Nevins, Study in Power: John D. Rockefeller, Vol. II (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1953), pp. 314-319. Woodward, pp. 402-404. 15. Woodward, pp. 397-406.

16. Nevins, p. 326. Fosdick, p. 10.

17. Boccaccio, p. 33. Nevins, pp. 302, 326.

18. Stiles, “Early History of the Hookworm Campaign,” p. 303. Nevins, p. 326. Williams, pp. 25-26. Minutes of the RSC meeting January 15, 1910; in RSC Collection, Rockefeller Foundation Archives [hereafter RFA].

19. Quoted in Sullivan, p. 327. James Cassedy, “The Germ of Laziness in the South, 1900-1915,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, XLV (1971), p. 165.

20. Buttrick speech, December 22, 1925, in Buttrick papers, RFA.

21. Wickliffe Rose, Report of Administrative Secretary (Washington: RSC, 1910), pp. 3-5, 31.

22. Wickliffe Rose to Walter Page, October 29, 1910; Page to Rose, Novembers, 1910, all in RSC, RFA.

23. Wickliffe Rose to Dr. A.W. Freeman, March 3, 1911, in RSC, RFA.

24. RSC, State Systems of Public Health (Washington: RSC, 1910) pp14-18; Wickliffe Rose to Dr. Morgan Smith, May 12, 1910, RSC, RFA.

25. Smith to Rose, quoted in Boccaccio, p. 44.

26. “Hookworm Conference” in Journal of the American Medical Associatin, 1910: Vol. LIV, No. 5, pp. 391-395; No. 6, pp. 484-486; No. 7, pp. 558-560; No. 8. pp. 644-646.

27. Rose to Stiles, May 19, 21, 1910, RSC, RFA.

28. Charles W. Stiles, Report of Scientific Secretary, February, 1910, p. 4, RSC, RFA, also Charles W. Stiles, First Annual Report of Scientific Secretary for the Year Ending January 25, 1911 (Washington: RSC, 1911), p. 19.

29. Stiles, Hookworm ...to the Negro, pp. 4-6. Stiles, Report of the Scientific Secretary, 1911, pp. 19-20.

30. Woodward, pp. 350-351. See George Fredrickson’s chapter, "Accomodationist Racism and the Progressive Mentality” in The Black image in the White Mind (New York: Harper & Row, 1971).

31. Marion Hamilton Carter, “The Vampire of the South,” McClure’s Magazine, XXXIII (October, 1909), p. 631.

32. Dr. Charles T. Nesbitt, “The Health Menace of Alien Races,” The World’s Work, XXVIII (November, 1913), pp. 74-75.

33. Frances Maule Bjorkman, “The Cure for Two Million Sick,” The World's Work, XVIII (May, 1909), p. H608.

34. Charles W. Stiles, Soil Pollution as Cause of Ground Itch, Hookworm Disease, and Dirt Eating, RSC publication No. 1 (Washington: RSC, 1910), p. 22.

35. Joan Bicknell, Pica: A Childhood Symptom (London: Butterworth and Co., 1975), pp. 4,91-94.

36. Robert W. Twyman, “The Clay Eater: A New Look at an Old Southern Enigma," Journal of Southern History, XXVII (August, 1971) pp. 443-447.

37. RSC, Second Annual Report (Washington: RSC, 1911), pp. 8-9.

38. Rose, Report of Administrative Secretary, pp. 11-12. Boccaccio, p. 40. Williams, p. 46.

39. Rose, Report, pp. 18-19.

40. Statement of Dr. Cully made May 29, 1939, from Personnel Record, RSC, RFA. The dispensary method had been first used in the early 1900s in Puerto Rico by one of Stiles’ students, Bailey K. Ashford. Sullivan, pp. 309-310. Farmer, p. 88.

41. RSC, Second Annual Report, p. 24; RSC, Fifth Annual Report (Washington: RSC, 1915), pp. 22-23.

42. RSC, Third Annual Report, p. 24; RSC, Fifth Annual Report (Washington: RSC, 1915), pp. 22-23.

43. Statement of Dr. Bell made February 10, 1939, from Personnel Record, RSC, RFA.

44. RSC, Third Annual Report, p. 19.

45. RSC, Fifth Annual Report, p. 13-14.

46. Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1916, p. 81-82; RSC, Fifth Annual Report, pp. 23-24.

47. See Statement of Dr. Carl Grote, January 21, 1939, Personnel Records of RSC, RFA.

48. H.F. Farmer, The Hookworm Eradication Program in the South, 1909-1925, PhD Dissertation, 1970 (Ann Arbor: University Microfilms, 1972), pp. 113, 121. RSC, Fifth Annual Report, p. 26.

49. Walter Page, “The Hookworm and Civilization,” The World's Work, XXIV (September, 1912), pp. 504, 509, 518.

50. Williams, pp. 51-52. 51. Stiles, “Early History of the Hookworm Campaign,” pp. 304, 306. Sullivan, pp. 331-332. E. Richard Brown, “Public Health in Imperialism: Early Programs at Home and Abroad,” American Journal of Public Health, LXVI, 9 (September, 1976), pp. 879-903.

52. RSC, Fifth Annual Report, pp. 17, 37, 43; Williams, p. 47.

53. RSC, Fifth Annual Report, pp. 26-27.

54. Rockefeller Foundation, Annual Report, 1916, pp. 89-90; Farmer, p. 118. 55. Williams, pp. 94-95.

Tags

Allen Tullos

Allen Tullos, a native Alabamian, is currently in the American Studies graduate program at Yale University. (1978)

Allen Tullos, special editor for this issue of Southern Exposure, is a native Alabamian. He is currently in the American Studies graduate program at Yale University. (1977)

Allen Tullos, a native Alabamian, is a graduate student in folklore at the University of North Carolina. (1976)