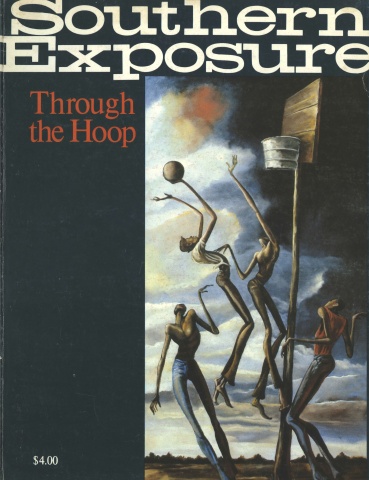

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

Will Gracey was flying! There was no time, no space, no dimension beyond this emerald roaring wet chamber in which he crouched, hurtling toward a sunlit opening that promised golden diamonds on bright blue water. Only this moment existed, now, where his right hand traced exquisite lines along the liquid wall that rushed up, out, and over his head in such fluid perfection that Will thought his heart would burst. Never in all his conscious memory had he felt such a surging joy as this. In that instant of detachment, the wave pitched quickly higher and collapsed into a five-foot wall of whitewater that pounded Will against the bottom and carried his surfboard to shore like a strip of shiny driftwood.

“To hold infinity in the palm of your hand,” Will muttered, as he sat scooping up the coarse wet sand and dropping it aimlessly on his feet. His breathing was back to normal, but his arms still felt too weak to even raise beyond his waist, so there was nothing to do but sit there and squint into the early morning sun that sparkled off the smooth blue swells, or carefully study the color and texture of the billions of sand grains lying in a four-foot radius around him. At that moment, he did not want to watch the ocean — partly because he knew the glare would give him a headache, but mostly because he needed to hold the image of that last ride awhile longer before being distracted by other waves and other riders.

He’d come so close that time. From the moment he chose the wave, Will knew that something was really right about it. Perhaps it was the feathering peak, the long moment of hesitation when the wave started to lift the tail of the board before it began its downward slide, or perhaps it was the way the wall tapered to the right; at any rate, Will had carved a smooth powerful bottom turn, come racing back up the face of the wave and neatly tucked under the curl just as it began to pitch out. Crouched as he was on the nose of his board, his right leg bearing the weight, his left extended forward for balance, he could see nothing but sunlight and water. His feet read the vibrations, fed impulses to the brain and received corrections of weight displacement and trim as subtle as any attitude thrusters ever designed.

The constant descent of his board had been perfectly matched to the upwelling of the water, so he remained locked into the hollow chamber that formed just ahead of the collapsing wave. At first, the sensation of speed was incredible because the water was rushing by, the board dropping, and the air forced out by the collapsing sections behind made a steady roar. Then, with everything lined up exactly, all motion seemed to stop and everything hung suspended in the diffused green-amber light of the liquid cylinder. The emerald eternity lasted less than three seconds.

Will dusted the last grains of sand off his hands and laughed at himself. Here he was, reveling in the same mystic mother ocean, cosmic mumbo-jumbo that he had always detested in others. Granted, he’d had a few seconds where the linear sequence had been suspended and he had felt completely alive in that very moment, but that sort of peak experience was hardly the exclusive property of surfing. Almost all religions and almost every other sport promised the same moments of illumination if pursued with fervor. Hell, hadn’t he been part of a generation that abused perhaps the widest variety of drugs ever conceived in search of a shortcut to that same feeling? If there was a mystery here, it had to be the timing of this experience; it was nearly 10 years too late.

Will Gracey was 31, and, up until a month before, had lived in Charlotte, been a high school history teacher and a part-time insurance salesman. He had also been married. Except for brief holiday visits to his parents’ house in Florida, this was the first time he had been to the coast in nearly five years. Louise had always preferred the cool mountains of western North Carolina to the thick heat of the Outer Banks in August.

He had rented the beach house at Buxton for many unclear reasons, but most of them centered around memories of a happier time. Throughout his childhood and even into college, the beach had always been Will’s refuge. For all he knew he’d been born knowing how to swim — at least he couldn’t remember learning to swim — and his parents had always let him roam the beach unsupervised. These last two weeks had almost been like that again. Walking across the cool textured crust of a rain-soaked dune in the first light of morning, he had been washed by overlapping memories of other times and other beaches, all pleasant.

If he didn’t think about it too much, Will could sometimes go for hours believing that it could all be like that again. He found it hard to imagine how he’d ever brought himself to leave it. He could blame it on Louise, whose beachcomber fantasy quickly melted in the sticky heat of summer, but it was really the developers who were most responsible. From Patrick Air Force base to Cape Canaveral, hardly a scrub tree stood after the land speculators and dream sellers were through peddling their wares. Overcrowding, erosion of the beach, and a depressed job market finally drove him inland and eventually delivered him to Charlotte. But his dreams were always of the ocean.

Now, sitting beneath the looming bulk of the Hatteras Light, Will watched the powerful groundswells march in. Somewhere far west and north of the Cape Verde Islands, a hurricane named Elisa was churning through the mid-Atlantic at a steady six knots, gaining force and sending out these waves like so many skirmishers. It was too early to be more than slightly apprehensive about it, so these first few days were a surfer’s delight. The wind blew cleanly offshore, keeping the waves smooth and hollow, and they had not yet gotten much over four to six feet. In this type of surf, Will was still relaxed and confident, even if his paddling muscles were slow to recover from their five years’ atrophy. If he timed the sets right, he could paddle out without getting his hair wet, but if he timed it poorly, he exhausted vital energy punching through breakers. A lost board meant a long tiring swim and another long paddle, so he rode conservatively, choosing only those waves with promising walls. The borderline closeouts would have to wait.

From that first day when he had strolled as inconspicuously as possible into the local surfshop and laid out S60 of his rapidly dwindling state retirement money for the vintage 7-foot-2-inch Bing “Foil,” he had surprised himself with how much ability he still retained. For sure, the timing was gone for things like going backside, or jamming a hard cutback, but the bread and butter stroke-into-the-wave-drive-off-the-bottom-and-line-up-the-wall moves were still there. Only his poor upper body conditioning and sensitivity to the sun prevented him from staying out all day. Gradually, over the last two weeks, his skin had darkened and his back and shoulders began to feel taut.

Last night, when the sound of the surf booming woke him sometime before dawn, Will knew that the morning light would reveal the first tentative probings of what promised to be the first major Atlantic hurricane in 15 years. He’d felt the adrenalin rush up his neck two nights ago when the news reported the hurricane’s formation. Hurricanes, too, were peak experiences, and Will surveyed the sturdy cypress stilt house, perched eight feet above the ground and a half-mile back off the ocean, with a sense of satisfaction. It had remained standing through other hard blows, so if Elisa should home in on the Outer Banks, he was certain it could withstand full-force winds. Only the shake roof worried him, but he knew the rationale: let the wind have as many shingles as it wants so long as the roof stays on. If the blow should come, he would ride it out right there in the house.

He had prayed for hurricanes in the early days, right after the first surfboards were unpacked with the household belongings of NASA engineers transferred from California. The sneering children of these transplanted specialists were unimpressed with the three-foot wind swells that broke most of the year and did not believe the stories of 10-foot storm surf. Since he was local (born and raised on the swelling fortunes of Indian River Citrus), Will felt he had to defend the area. He even disdained the California boards in favor of a 9-foot-6-inch James & O’Hare, carefully crafted in Cape Canaveral, just north of the new pier.

Even then, in 1963-64, surfing had been a quest of sorts. In those days, the search for better wave breaks sent Will and his friends up and down the length of A1A. The pattern was always the same; they drove down in the early morning coolness whenever Cocoa Beach was flat and began to explore the overgrown sandy trails that cut through the dense palmetto-covered dune. Sometimes, they would walk over the dune and look down to see excellent four-foot waves popping up off a submerged coquina reef, peeling smoothly left and right.

At times like this, they felt like Balboa and would name the place after some notable feature. To the south some 20 miles, they found Shark Pit, Spanish House and Sebastian. To the north they found Pig Farm and the Jetties. And beyond the Jetties, wavering in the salty haze, was the tip of Cape Canaveral, isolated by three miles of Strictly Off-Limits Government property. The shady grove of Australian pines, the white beach, the empty waves that wrapped riderless around the point still haunted Will’s memory. He hadn’t been out there since he was seven years old, but he remembered that the place was more beautiful than anywhere he had imagined. The pines offered shade, the breezes were cool, and the tidal pools held many treasures. His father used to put him on his shoulders and wade out into the surf where Will could dive into the incoming swells.

He always remembered the first five years as a time when the mornings were clear and warm, the surf smooth and hollow, and the surfers all friendly in the awareness of this shared experience. It was all fused into one image of a Saturday morning sometime in the spring of 1965, when he and two friends were driving south toward Shark Pit. The morning sun was dancing along the periphery of his left eye, in and out of the Australian pines, as he drove his beloved green ’55 Ford station wagon to the tune of the Beatles’ “Eight Days A Week.” In Melbourne Beach, a surfer walking beside the road grinned and gave them the thumbs-up assurance that there were good waves. They were not disappointed, and that day Will had come very close to the feeling he’d experienced this morning. Later that same afternoon, lying in the sand with the sun beating down on his back, he couldn’t think of anywhere in the world he would rather have been.

But there were also the dark days. Part of his mind worked constantly to blot out the memory of cold gray November storms. He’d nearly drowned in the churning indifference of those unmakeable peaks; only the desire not to be a horrible limp blue body like the one he’d seen washed up when he was six gave him the strength to make it ashore.

And now, sitting here 15 years after his first exhilarating slide to shore, standing on a borrowed surfboard Will wondered how he had ever drifted away from the sport. Certainly, it had been the focus of his life throughout the ’60s, to the extent that it influenced every lifestyle decision he made. The automobiles that he lusted after were not the full-blown GTO’s that blipped through the burger parlors, but rather VW microbuses and fixed-up Falcon Vans. You could cruise to California in a van, sleeping shifts, driving non-stop, and be there in a little over two days. You could camp self-contained along the Outer Banks.

It was the same with clothes: comfort won out over style every time, until it became style. Blue canvas boat shoes, sand-colored corduroys, and Penney’s T-shirt with the pocket constituted formal dress. Canvas baggies, or quick-drying nylon ones, a Hawaiian-print shirt and 39-cent flip-flops took care of all other occasions.

Those were simpler times all around, Will thought, shuffling back toward the house, his board tucked under his arm. The surf was getting bigger, he could tell, and he knew his limitations. He decided to thumb up to Kitty Hawk for the afternoon.

Standing in front of the full-scale replica of the Wright Brothers’ Flyer, Will felt a sudden shiver of recognition. This, too, was a product of a simpler time, yet it represented state-of-the-art technology on a blustery day in 1903 when it flew that pitifully short distance marked outside at the base of Kill Devil Hill. A mile or two south, at Jockey’s Ridge, children were staying aloft for hours on delta-winged air foils designed by a NASA engineer named Rogallo for the specific purpose of bringing home the astronauts — heirs to the Wright Brothers’ dreams.

Will studied the curved fabric-covered wings. This is truly a craft designed for flight, he thought, a lifting body that would enable a person to soar off the wind currents like some graceful seabird, rising and dipping from thermal to thermal. The motor was mere expedience — a means to propel the plane fast enough to get it airborne, to let it break free of the earth, but still to glide on the natural currents. He mused at how far flight technology had come over the last 75 years; propellers become propellants, pilots become projectiles, until now humans were thrust off this planet in devices that, if the power failed, would not glide an inch, but rather plummet like Icarus, wings melting, into the ocean.

Perhaps the Wright Brothers’ tools were only toys now, but the essence of flight lived more surely in them than in anything produced by the aerospace industry. Surfing held to that spirit also, and that accounted for its attraction to the children of nose-cone re-entry specialists, propulsion engineers and systems analysts. While the parents were sweating out the mathematical calculations for another imprecise mid-Atlantic recovery, their children were gleefully harnessing the wave-form energy produced by wind on water, and riding it easily to shore. Will felt vaguely as though he were standing in front of a shrine to something more than flight — or perhaps to real flight in whatever form. After all, the technology of this first airplane eventually brought NASA families to Cape Canaveral, and they brought surfboards from California. And, to close the circle, the same wind forces that brought the Wrights to the Outer Banks now drew the surfers. Nowhere on the East Coast do the waves approach the magnitude of Hatteras. And Hatteras was about to put on a show.

The sun rose red and diffused on the morning of August 23rd. A high strata of grayish cloud covered the sky from horizon to horizon. The barometer read 29.80 and dropping. Hurricane Elisa was stalled at 32 N75, with maximum winds of 115 mph and strengthening. The Eastern seaboard from Savannah to Norfolk was on hurricane alert. Twelve-foot waves roared across Diamond Shoals and wrapped around the tip of Cape Hatteras, where Will stood gaping in slack-jawed awe. He’d seen films of bigger surf than this in Hawaii, but nothing prepared him for the raw power of these waves.

They came in like freights, one after another, gray, thick and swift, shaking the beach with the force of their concussion. He hadn’t even brought his board down with him because he knew that from here on out he was back to being a spectator. He would leave hurricane surf to those who had made the narrow commitment to excellence that he had never been willing to justify. And there were more than a few of them there that day.

A quarter mile out, they bobbed, perched like pelicans on the sleek shapes of their big-wave boards. This was grim sport today. Each wave was carefully chosen, because in surf this heavy it was suicide to use a leash and a lost board meant an hour and a half swimming in and then trying to fight back out. A person could easily drown in the arm-numbing fatigue of two consecutive miscalculations. But, if your conditioning was good, your attitude right and your skills sharp, these waves offered mind-altering experiences.

Will watched one of the surfers stroke into a huge wall, fighting the incredible updraft created by the offshore winds. Too much time passed and the wave went vertical as the surfer finally stood up, only to free-fall eight feet and be crunched by a collapsing wall of whitewater. His board shot spinning high into the air, landing fin up in the trough, while Will counted to 20 waiting for the surfer’s head to pop up. Finally, it did, some 30 yards closer to shore than his board. Will wanted to cry out and point, or something, to tell this stunned waverider that his board was behind him, but it was too late anyhow. The next wave picked the board up like a chip and sent it flipping to shore, churning carelessly over the weary swimmer.

Outside, another rider paddled smoothly into a large peak, stood quickly, bottom-turned, and drove hard for the shoulder. Incredibly, Will watched the figure standing erect, back slightly arched, as the lip of the wave threw out over his head and formed a six-foot pocket into which the surfer faded. For seven full seconds the rider remained inside the tube while Will danced a jig on the dunes. As the wave began to close out, the surfer dropped, then jammed up hard, popping out the back of the wave still standing, with both arms raised, exultant.

Will was beginning to understand just exactly what it was that drove people to dedicate their lives to the act of doing one thing in this world better than anyone thought possible. All the hours, all the practice, all the other pleasures sacrificed could, he began to believe, be cancelled out by the utter joy of approaching perfection. He thought of all the things in which he’d dabbled — sports, education, job, even marriage — up to that point of diminishing returns, where the additional time spent resulted in only the most marginal improvements, and he wondered if he had the courage just once to take something to the limit of his ability. Could he, at this late date, make that narrow commitment from which he’d shied so long? It didn’t have to be surfing, but it did have to be some pursuit that enabled him to finally break through the feeling of waste that had been closing in on him for the last few years. A shiver of excitement danced along his spine.

Elisa began to move west-northwest at eight knots, and all residents and visitors of Dare County were urged to evacuate the Outer Banks immediately. Will looked over at the dining room table where two grocery bags full of canned goods waited to be put away. A gallon of Coleman fuel, two boxes of candles, and a five-gallon thermos sat beside them. If the hurricane maintained its present course he would be sitting in the middle of it this time tomorrow. His heart beat rapidly.

The sunset that evening was fiery and foreboding, but the sky to the southeast was awesome. Barely above the horizon out over Diamond Shoals, where the high strata clouds seemed to converge, Will could see the whitish bar of thick cloud layer that marked the outer fringes of this massive storm. Low scud clouds moved at rapid angles to the higher wisps, tinged with pink in the early dusk. The wind was backing again northwest, going northerly, and he knew tonight would be oppressive. He would hold off as long as possible nailing tight the heavy wooden shutters. At least he could sleep in the hammock and not be bathed in his own sweat. For a moment he felt very lonely.

There was no dawn. At least, there was no discernible lightening of the eerie world outside that hurled wind and rain heavy as slate against the battened walls of the beach house. All night the gusts became stronger and the heavy squalls that roared across the dunes had finally come so close together that only occasional shifts in intensity modulated the steady wail. The force that howled at the pilings and pried at the windows was greater than anything Will could remember from childhood.

He realized now that he’d slept through most of the previous hurricanes, secure in the trust of his father’s watchful care. Only in this moment did the memory of his father pacing in the night from window to window, flashlight in hand, come back to him. They’d had a boathouse once when he was very young. One day it sat in the Indian River, its red tin walls radiating heat like a stove, and the next day it was gone without a trace, leaving only some twisted pilings.

Hour by hour the intensity grew. The house shuddered and groaned under the sudden gusts that shrieked full-on for interminable minutes. In those moments, Will fought his panic any way he could. He was sure now that the sea was running up under the house and he knew what a strange vision this must be — a lone beach house, stilted gray survivor in a whirling wasteland of surf and spume, waiting. . . .

Will forced himself to think of something other than the hurricane. He tried to think how he’d come to lose touch with the beach, with surfing, with himself. It had to do with the times, he decided.

Back then, he had managed to drift through the first two years of college while staying out of the draft, managed to surf most every weekend, and had occasionally lent his body to the anti-war movement. He’d quit the track team after his sophomore year, once he’d realized he would never be faster than a 10.3 sprinter without a whole lot more work than he was willing to give it. Even though the assassinations of King and Kennedy left him a little numb, they didn’t really affect him as much as he would have pretended if asked. But short surf boards, Chicago and the Apollo missions did.

Since the Spring of ’68, when the first V-Bottoms had made his 9-foot-4-inch nose-rider obsolete, Will had been fighting a losing battle. The lower volume of those high performance boards meant less flotation and more critical takeoffs. This required better conditioning on the part of the surfer, and he couldn’t maintain it as a weekend rider. With the long nose-riders that he’d owned before, Will had become a competent water dancer, as he liked to think of it. The board was a moving platform, a stage upon which to perform. Now the 14-year-olds were giving him lessons in the new harmony between board and rider. He couldn’t stand it.

Things had improved for awhile that summer when he had time to surf every day and get the new boards wired. He even toyed briefly with the idea of laying out of school a semester and heading out to California with some of his friends, but the thought of Viet Nam hung too heavily in the air. He had watched the Democratic Convention on TV, hoping to see some of his friends from school who were McCarthy delegates. It was awful. He couldn’t believe the barbed wire, the armored personnel carriers, the tear gas, the troops and the beatings. Will seethed at the smug delegates who sat safely inside while the storm of protest raged outside, but he was really sick at the thought of all those like himself who sat at home, even safer. After that, surfing had begun to seem somehow too frivolous for those depressing times.

Only the excitement of the Apollo 8 mission shed any joy on the close of the year. The crackling voice of Frank Borman and the stunning vision of the Earth from 20,000 miles in space had left him awed. The sheer logistics of this feat baffled him and rocked Cocoa Beach like Mardi Gras. Three men had fled this planet atop a streaming cylinder of fire, and they had carried that fire, that light, to the dark side of the moon and returned. Will felt buoyant, but this feat and the lunar landing later the next year were only isolated bright moments in black times.

The wind shook the house and he moaned suddenly out loud, scaring himself with the sound of his own strange voice. Something struck hard against a piling, sending the shock up through the floor, and his heart quailed. Had he ever been alive when the wind did not beat in madness against the house? Did the sun ever shine bright and quiet upon a stretch of beach that moved in languid ease through each day? Was the ocean ever green? Please let it end. Please, please, no more.

Suddenly the wind subsided and the rain abated. A deadly silence fell over everything and light streamed through the cracks in the shutters. Will was stunned by the change, and he sat on the bed for fully five minutes before he realized what was happening. The eye was passing.

Nothing in his life had prepared him for the spectacle that he viewed from the porch. The debris, the piles of flotsam wedged here and there, the sea oats flattened atop the dunes he had expected; but the sky was another thing altogether. From horizon to zenith in every direction, it was fiery-red, the Earth an inferno of diffused crimson with Will alone in its center. Directly above him, where the clouds almost thinned completely, it burned bright copper. Gentle winds gusted lightly from all quarters and he almost expected birds to be singing. Will very nearly felt reprieved in the magnificence of this sunset’s flaming vortex. He found it difficult to believe that the hurricane wasn’t really over.

More suddenly than it eased, the storm slammed back against the house, this time attacking from the northwest with redoubled fury. Night fell like black rain and Will’s spirit cracked like a spar.

Somewhere outside, a high keening shriek rose and fell, with the wind turning his insides to ice. Will had been beaten helpless by the storm for over 11 hours. In his heart he knew, now, that it would never end — that it would go on, endless, with no day, no sky, no earth, no silence, nothing but this roaring, howling, driving wind and water for all black eternity. He thought of all the things he’d meant to do and had not.

He thought of the disappointments and pain he’d caused others, and he wished with all his heart that he could live his life over. He prayed and made promises, and finally slept, exhausted and without hope. Will dreamed. He distinctly heard his father’s quiet footsteps in the living room, crossing toward the hallway to his room, the beam of the flashlight swinging its yellow arc before him. Overjoyed at the thought of seeing his father, whom he’d thought to be long dead, Will struggled to sit up, but could not. He felt paralyzed between sleep and consciousness, and he had the sudden panicky fear that it wasn’t his father coming down the hall, that instead he was dying.

He strained and tried to cry out, but he was held mute by an incredible heaviness. Tears ran from the corners of his eyes. But it was his father, quietly checking the window before pausing beside the bed to look down at him with mild eyes. Will quit struggling and was instantly awake. He looked about the room in quiet desperation, remembered where he was, and realized, suddenly, that the storm had finally passed. Only occasional gusts pressed against the house and the rain was intermittent. Glancing at his watch he saw it was a quarter to five.

Dressed in an old flannel shirt and shorts, Will walked barefoot in the deep cut between the dunes. The sky was just growing light over the Gulf Stream where the waves jumped up jagged as shark’s teeth. Will was elated. He looked at the altered landscape of eroded dunes, endless seaweed and jumbled driftwood with no feeling of desolation, but instead a sense of seeing the world transformed. Every shell, every glinting particle of sand had significance — shifting, eroding, replenishing and then deserting this fragile strand in an endless cycle in which nothing was actually destroyed. He saw it all as so many small gestures, ebbing and flowing with the wind and tide, day in and day out, always mutable, always affirmative.

Will thought about the night before. He remembered his promises.

Tags

Bill Atwill

Bill Atwill was born in Cocoa, FL, and has taught English at Florida Institute of Technology and Mars Hills College in the North Carolina mountains. (1979)