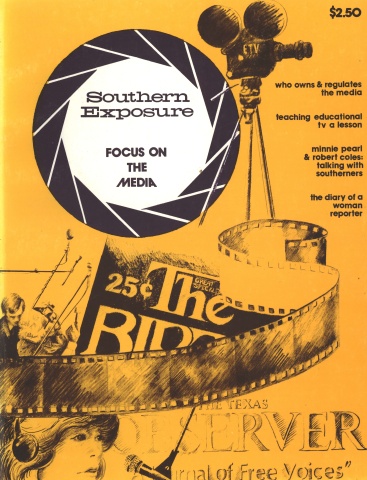

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

"The American people should be made aware of the trend toward monopolization of the great public informational vehicles."1 — Spiro Agnew

Raiding the South for lucrative newspaper and broadcast stations has become commonplace in the last decade. Lured into the nation's fastest growing region by statistics which reveal expanding newspaper circulation and advertising revenues, outside corporations are falling over each other in search of willing sellers. Media has become a growth industry, and the biggest companies in the field want to grow with it. They're taking the profits from their chain of newspapers or television stations and buying up any and all available media outlets. As a result, ownership of the South's media is becoming more and more concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. Alas, it is as Spiro warned.

I. The Takeover

Back in the 1930s, outsiders buying up newspapers were an oddity. Col. Frank* B. Shutts, owner of the Miami Herald, thought he made a killing when he sold his paper for $3 million to John S. Knight and associates of Akron, Ohio. But Knight turned out to be the smarter capitalist. His Miami Herald, valued in excess of $75 million, now anchors a media empire containing sixteen newspapers (11 in the South), plus partial ownership of a television station in Ohio and eight radio stations.2 Another Ohio investor, James M. Cox, began expanding into the South in the late 1930s with his purchase of the Atlanta Journal. The well-respected Cox acquired the nickname "governor" after his term in Ohio's mansion, but he was not above employing a common practice to increase his control of an area's media: he bought out his competitor, the Hearst chain's Atlanta Georgian, and simply shut down their presses. Then in 1952 he bought the Atlanta Constitution, and through the affiliated Cox Broadcasting Company, now owns an Atlanta television and AM-FM radio combination. From its Atlanta headquarters, the intricate Cox conglomerate (see box in map) now controls twelve newspapers (ten in the South), five television and nine radio stations, plus a sprawling cable TV interest, a technical book publishing company, and a movie production outfit (makers of Willard and Walking Tall).3

The media buying spree escalated during the 1960s with the aging, yet feisty Samuel I. Newhouse leading the way. As the decade opened, Senator Wayne Morse told Congress, "The American people need to be warned before it is too late about the threat that is arising as a result of the monopolistic practices of the Newhouse interests." Two years later, Time magazine reported, "With insatiable appetite, newspaper publisher Samuel I. Newhouse —who has already bolted down 14 dailies —is in the process of swallowing three more. And Sam is still hungry. Last week, he began to spread the table for the biggest feast yet. On the menu, the New Orleans Times-Picayune and its evening companion, the States-Item." The price for the New Orleans papers was a record $42 million, but that did not stop Sam. Today, at age 85, the five-foot, three-inch whirlwind boasts: "I am not a chain publisher. I want to be a creative custodian of newspaper tradition and newspaper effectiveness."4

Big chain ownership has indeed become the tradition of newspaper publishing. By 1967, groups owned 49% of the nation's dailies, accounting for 62% of the total circulation. In 1970, only 4% of the nation's cities had two or more separately owned newspapers, while the figure was 21.5% in 1930 and 57% in 1910.5 In the South, the number of group-owned papers leaped 36% alone in the five years from 1965 to 1970. By 1974, 248 of the 430 dailies in the 13-state South were controlled by chains or companies owning more than one newspaper. In the same year, companies with interests in two or more television stations owned 126 of the region's 225 stations.6

The statistics for the top ten metropolitan areas in the South dramatize this pattern of concentration: in eight of the ten cities, a newspaper and television are jointly owned; groups control 29 of the 43 TV stations and 13 of the 18 papers in the areas; only two dailies —the St. Petersburg Times and Houston Chronicle — have no other newspaper or television interests, and the Chronicle hardly qualifies as a small outfit. It's owned by the Houston Endowment, described by one investigator as a "tightly held corporate force" with "a majority interest in twenty-five [corporations] , including a half-dozen banks, three hotels, several downtown office buildings, real estate, and the Mayfair House Hotel on Park Avenue, New York."7

The chains owning the metropolitan South's media vary in size from subsidiaries of multinational corporations, like RKO General (a division of General Tire & Rubber), owners of Memphis' WHBQ-TV and other stations in New York, Boston, and Los Angeles; to the national chains, ranging from Newhouse and Scripp-Howard to the Outlet Company (owners of KSAT-TV in San Antonio, WDBO-TV in Orlando and others) and Hubbard Broadcasting (WTOG-TV in St. Petersburg/Tampa, etc.); to the regional chains like Bahakel Broadcasting Stations (Charlotte's WCCBTV, Montgomery's WKAB-TV, Greenville, Mississippi's WABG-TV-AM, Jackson, Tennessee's WBBJ-TV, and radio stations in several southern cities); to state chains like A.H. Belo Corp. (Dallas News, six smaller Texas papers, WFAA-TV in Dallas and KFDM-TV in Beaumont); to the city-based combination, like the Louisville Courier Journal and Times and its WHAS-TV or the

Houston Post and its KPRG-TV. Whatever the form of ownership, or size of corporation, all of these companies have one thing in common: they restrict the number of sources of news and information available to the public. To many critics, including former FCC commissioner Nicholas Johnson, multiple ownership of so many media outlets "is greater than a democracy should unknowingly repose in one man or corporation."8

II. Why Concentration?

If diversity of news sources appeal to your patriotic instincts, it is considered anathema to the established interests. From their perspective, the introduction of new forms of communication means competition, i.e. a threat; consequently, newspapers moved into radio, radio into TV, television moved into cable TV, and the groups moved all over the map, attempting to corner the development of new technologies. Profits could only be protected by expanding control over new media. In fact, an expanding company can boost the market value of its stock through its acquisition program, use the higher price stock as capital for purchasing another paper or broadcast station, and pay no taxes on the transaction.

In addition to these general principles of corporate economics, two important tax laws have fueled the proliferation of chain ownership and the disappearance of the independent newspaper. The inheritence tax has proved an insurmountable stumbling block to many local, family-owned newspapers, forcing many heirs to sell out to the highest bidder rather than face a walloping tax bill. On the other hand, a court ruling shortly after World War II provided a tax advantage to newspaper chains using their profits to purchase more papers, thus increasing the number of buyers in the market. The result, as one group executive says, is that “buying a newspaper is like an auction." Agents for the chains converge on a willing seller, prices are bid up, and the whole thing is written off as a “reasonable need of business" to avoid the 38 ½ % accumulated-earnings tax.

Media chains defend their bigness by claiming that the local broadcast station or paper benefit from access to a Washington bureau, syndicated columnists, high-salaried reporters, and the latest in equipment. Veteran media critic Ben Bagdikian counters that such mass production tends to "Howard Johnsonize" news coverage, for the goal is to standardize operations to attain level profits, rather than locally-responsive news reporting.9

Furthermore, the "eccentricities in the individual" editor which provide the paper's unique approach are lost under group ownership, charges Frank A. Daniels, Jr., third generation publisher of the family-owned Raleigh News & Observer. And says Daniels, groups "may or may not improve the operation" of the paper, for quite often profits are not reinvested locally, but are used for the stock pricing and acquisitional needs of the chain.10 In these ways, the so-called independent publishers, whose editorial views were well-known and whose lives revolved around the communities' newspaper, have steadily disappeared. Replacing these local barons are distant kings, not in as direct control perhaps, but still in a position to influence what vast numbers of people read and hear.

Nelson Poynter, publisher of the independent St. Petersburg Times, links this critique of outside group control with "the loss of local ownership — banks and department stores — . . . that was the heart of the city. Now the editors and people running [newspapers] are simply employees, unless they own 51 percent of the stock. They are subject to move. Therefore, our cities lack roots ... we are losing that glue. A responsible newspaper should be the soul of the city. The chains say they give absolute autonomy to their editor. But he is on a leash."

Of course, local ownership does not necessarily insure that the newspaper will be responsive to the community's interests, as the case of the Bluefield, West Virginia, Daily Telegram discussed later illustrates. Nevertheless, concentration of media in a few hands clearly runs counter to the most elementary provisions of constitutional democracy. As Justice Hugo Black wrote in a landmark decision, the first amendment "rests on the assumption that the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources is essential to the welfare of the public, that a free press is a condition of a free society . . ."12

III. The Regulators Fail

But the first amendment cuts two ways. Newspapers have used it to block any attempt to regulate their activities, mobilizing their powerful lobby around the precept that any regulation of their growth or day-to-day operations would violate the restriction against laws governing the "free press." In the name of the first amendment newspapers have even avoided filing routine profit reports required from other industries. A few years ago, Paul Rand Dixon of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) was asked by a Senate hearing why no newspaper data had been included in the reports of major industry profits issued by the FTC. Dixon replied, "I kind of suspect nobody wanted the newspapers mad at them."13 On another occasion, the newspapers withheld data requested by a Congressional committee attempting to develop legislation which the press opposed. As Morton Mintz and Jerry Cohen say in their chapter of America, Inc., titled "Hear No Evil, See No Evil, Speak No Evil," the "advocates of the people's right to know and enemies of secrecy in government were unwilling to provide Congress with the information it would need if it were not to legislate in the dark."14

And when the constitutional restraints run out, the print media does not hesitate to call forth its considerable lobbying muscle. Thus, when the courts found anti-trust violations in the typical price-fixing and profit-pooling agreement between competing newspapers who jointly own production facilities (as in the case of the Nashville Banner and Tennessean, the Miami News and Herald, Birmingham News and Post Herald) the newspaper lobby intimidated Congress into passing a special exemption bill for them.

Compared with the print media, regulators have more leverage when they tackle the broadcast industry, but concentration of ownership in a few hands has nonetheless occurred. Because airways are considered public, and the number of frequencies are limited, the Federal Communications Commission was established in 1934 to regulate and license broadcasters in accordance with the "public convenience, interest or necessity." For decades, a handful of FCC Commissioners and outsiders have attempted to use this power of regulation to block or even break-up the multiple ownership of broadcast stations by one company. As early as 1941, the FCC held hearings on the move by newspapers to buy up radio and television licenses in their areas, but the Commission steadfastly refused to rule against such cross-ownership of media outlets. Only after considerable pressure did it finally limit, in 1953, the number of broadcast units any one company could own to seven TV stations, seven AM and seven FM radio stations. Needless to say, substantial media empires are still possible under the ruling, particularly among the licensee in major population areas. WKY Systems, for example, has TV stations in Dallas, Houston, St. Petersburg-Tampa, and Milwaukee, plus indirect ownership of the Daily Oklahoman and the Oklahoma City Times. Storer Broadcasting owns WAGA-TV in Atlanta, several radio license and cable franchises, plus television stations in Boston, Detroit, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and Toledo. Today, not a single VHF television station in the country's eleven largest cities is outside the direct control of a network, a newspaper or chain, a broadcasting group, or an industrial or financial conglomerate.

In recent years, the controversy over newspaper ownership of broadcast licenses in their respective cities has been revived, largely by the pressure from the Justice Department and FCC Commissioners Nicholas Johnson and Kenneth Cox. More than 250 papers are involved in such crossownership; many of them have the gall to defend their control by warning that outside conglomerates would buy up the licenses if they didn't own them. Of course, many of the 250 are part of conglomerates, like the Times Mirror Company's ownership of the Dallas Times-Herald and KDFHTV. Johnson and Cox had little concrete evidence of the impact of crossownership on news coverage, but they brought the issue to center stage during the 1969 renewal hearing of San Francisco Chronicle's KRON-TV license. Star witness Albert Kihn, an eight-year veteran with KRON-TV, produced a memo urging the station's newsmen to give South San Francisco and its mayor favorable coverage at the time the San Francisco Chronicle was seeking cable television rights to the area. Kihn also documented KRON's intentional failure to report the revelation of a secret deal in which William Hearst would drop his News-Call Bulletin in exchange for a profit-sharing plan between his Examiner and the Chronicle. Finally, a reporter for the Chronicle testified that his column condemning TV violence was censored. Despite the rising clamor against the collusion resulting from such common ownership, the FCC approved KRON's license.15

With pressure mounting, the FCC proposed a new rule which would bar any new acquisition that would result in common ownership of two broadcast stations — TV, AM, or FM — in the same urban market. The Justice Department, which had pressed anti-trust suits against media concentration in the same market in the 1950s and 1960s, petitioned the FCC to expand the rule to include newspaper-broadcast combinations and to require divestiture of existing combinations. Before it acted on this suggestion, the FCC shocked the broadcast industry by refusing to renew the license of Boston's WHDH-TV, partially because it determined that the station's ownership by the Boston Herald Traveler contradicted the "criteria of diversification of communications media control." With the media conglomerate still reeling, the FCC next adopted its proposed rule blocking multimedia ownership in the same market, and recommended that the Justice Department's suggestion of including newspapers and ordering divestiture of existing combinations also be implemented.16

For awhile it looked like Johnson and Cox were making headway inside the Commission. But by 1970, the newspaper and broadcast industries had fully mobilized their powerful lobbies to circumvent FCC regulations through special Congressional legislation. Senator John Pastore, chairman of the Commerce Committee's Subcommittee on Communications, introduced a bill that would clip the FCC's wings by preventing them from considering competing applications at the regular triennial radio and TV license renewal hearings — in other words, the original function of the FCC to monitor broadcasters' performance every three years would be gutted. Fortunately, the bill never passed. Nevertheless, the pro-industry influence of the Nixon appointees on the Commission began gaining the upper hand. In late 1970, the new FCC chairman Dean Burch announced that the decision against WHDH-TV was unique and that "as a general matter, the renewal process is not an appropriate way to restructure the broadcasting industry."17

The Justice Department, however, did not abandon the issue of crossownership. On January 2, 1974, it filed petitions with the FCC against the renewal of the broadcasting licenses of three major publishers— the Pulitzer Publishing Company and the Newhouse chain in St. Louis, and Cowles Communications in Des Moines —on the grounds that their multimedia ownership represented illegal control of the advertising market in the two cities. Other suits began piling up at the FCC involving crossownership, including one filed by the Citizens Communications Center against the Bluefield, West Virginia, WHIS-TV and its partner the Bluefield Daily Telegram, both controlled by the Shott family. Poor blacks and miners represented by CCC charged that the Shotts discriminated against blacks in employment and programming and used their monopoly control over a good portion of West Virginia's coal fields to block any objective coverage of the Miners for Democracy campaign to reform the United Mine Workers.18

Finally, under pressure from the courts and the Justice Department to develop some rule on crossownership, the FCC reopened hearings in 1974. On January 28, 1975, it issued a rule "to prohibit newspapers in the future from acquiring radio or television broadcast stations located in their markets" and voted "to require newspapers to divest television or radio stations in sixteen cities" by 1980, where the only daily owned the only city-wide radio or TV station. Five of the seven newspaper-TV combinations affected were in southern cities, including Bluefield, West Virginia; the others are Anniston, Alabama; Albany, Georgia; Meridian, Mississippi; and Texarkana, Texas. Only one of the nine newspaper-radio combinations is in the South, in Hope, Arkansas.19

Critics of media concentration are not satisfied with the Commission's new rule and plan to press for further divestiture of existing combinations. The Justice Department, which had hoped the FCC would rule to break up all existing crossownership, may now have to begin the lengthy process of filing anti-trust suits on a case-by-case basis. An FCC ruling could have broken up all combinations in three years. The court approach will take much longer. But the media combinations are clearly alarmed, for even with the departure of Nick Johnson and Kenneth Cox, the public interest forces are gaining in sophistication and have more clout with the FCC. As a typical call-to-arms editorial in the industry's Broadcasting magazine admitted, "A majority of the commissioners are philosophically tuned to the prevailing wavelengths of the broadcasting business, but events are not altogether under their control. However they may personally dislike repressive regulation, they are beset by pressures from the outside that cannot be ignored."20 To avert a final showdown, newspaper and broadcast lobbyists are busily reminding politicians of media's crucial role during elections while asking for special legislation to protect their holdings, or at least weaken the power of the FCC. How well they will succeed is unknown.

Meanwhile, the right of a man or corporation to control media outlet chains in markets around the country remains virtually unchallenged. Other governments, most notably Great Britain, have already chosen to regulate all media transactions to guard against concentration of power. The Canadian Commission on Mass Media suggested that a monopolies board be set up to apply a single guideline: "All transactions that increase ownership in mass media are undesirable to the public interest unless shown otherwise."21 New legislation is clearly needed if the U.S. is to break the stranglehold corporate syndicates now have on information sources. Such a restructuring of media ownership will not come easily, for empires are not given up without a struggle.

FOOTNOTES

1. Spiro Agnew, 1969 speech, as quoted by M.L. Stein in Shaping The News (New York: Washington Square Press, 1974), p. 68.

2. "Southern Newspapers — Groups Plunge To Buy Them Up,” The South Magazine, Spring 1974, pp. 14-19.

3. Promotional Material, Atlanta Newspapers Inc., Cox Broadcasting Corp.

4. Richard Dodds, "Media Ownership in New Orleans," New Orleans Courier, October 3-9, 1974, pp. 4-8.

5. Morton Mintz and Jerry S. Cohen, America, Inc. (New York: The Dial Press, 1971), p. 96.

6. Editor and Publisher Yearbook, 1974, and Television Factbook, 1974.

7. Ben Bagdikian,"Houston's Shackled Press," Atlantic, August 1966, pp. 87ff.

8. Nicholas Johnson, "Media Barons and The Public Interest," Atlantic, June 28, 1968, pp. 43-51.

9. Ben Bagdikian, "The Myth of Newspaper Poverty," Columbia Journalism Review, March/April 1973, pp. 19-25.

10. The South Magazine, op. cit.

11. Ibid.

12. Justice Hugo Black, AP v. US, 326 US 20 (1945).

13. Ben Bagdikian, "The Myth of Newspaper Poverty,” Columbia Journalism Review, March/April 1973, pp. 19-25.

14. Morton Mintz and Jerry S. Cohen, op. cit.

15. Stephen R. Barnett, "The FCC's Non-Battle vs. Media Monopoly," Journalism Review, January/February 1973, pp. 43-50.

16. "Congress, FCC Consider Newspaper Control of Local TV,” Congressional Quarterly, March 16, 1974, pp. 659-663.

17. Dean Burch as quoted in Pam Eversole, "Concentration of Ownership in the Communications Industry," Journalism Quarterly, Summer 1971, pp. 251-268.

18. Interview with Ed James, United Mine Workers of America, February 3, 1975.

19. "Newspaper-Broadcast Cross Ownership Rules Amended by FCC (Docket 18110)," January 28, 1975.

20. Editorial, Broadcasting Magazine, December 23, 1974, p. 58.

21. "The Uncertain Mirror," Volume I of the Report of the Special Canadian Senate Committee on Mass Media, as quoted in "Canada's Media Report, Mirror of the U.S.?," Columbia Journalism Review, May/June 1971, pp. 21-28.

Tags

Bruce MacMurdo

Bruce MacMurdo was raised in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and contributed regularly to that city's underground paper, Gris-Gris. He now lives in Chapel Hill, N.C. —and is the crusading captain of the Southern Exposure basketball team. (1975)