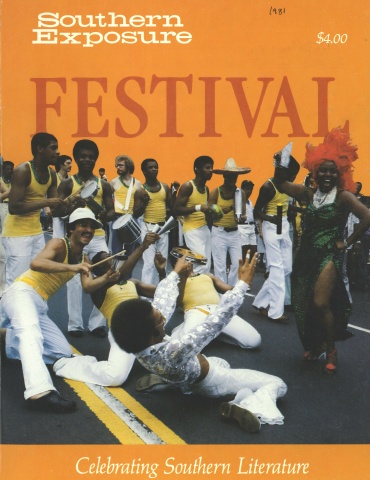

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

The South’s fascination with the romantic and the impossible has long mesmerized its politics, its literature and its own images of itself. “Romanticism was taken and acted on as the reality of things,” writes Marshall Frady in his book Southerners. “This sense of comprising some spiritual order of the outcast and benighted . .. was all the more beguiling to Southerners because the rest of the nation seemed so ready to collaborate in the conceit.”

But the South’s insularity, its racial preoccupations, its public presence as a dream of itself, are fast fading under the jarring influence of rapid changes and radical traumas: the struggle for civil rights, the Vietnam War, the boom of industrialization and attrition of older, agrarian values. This issue of Southern Exposure examines the relationship between the South’s social and political changes, and the interior, imaginative life of its writers. It is an issue about both art and survival. “I have written to stay alive,” says Alice Walker. “I have written to survive.”

At this juncture in our common history, it is especially important that we look to our artists to inspire and lead, for they celebrate the human spirit and our capacity to resist all efforts to strip us of our dignity. “Who, brothers and sisters,” asked Ossie Davis at the recent Black South Literature and Art Conference, “is to remind us of our humanity, to plant within us again the seed of spiritual greenness, to make possible even in this concrete jungle that we now call home, that flowers of resistance and patience — mankind’s best offerings - will indeed bloom and blow again - is that not the responsibility of our artists?”

Much of the variety and vitality in Festival comes from cultural traditions not often heard outside their own communities. Marilou Bonham-Thompson writes of her experiences as a poet with Cherokee heritage. Carmen Tafolla surveys chicano writing, while Barry Jean Ancelet and Mathe Allain examine the renaissance of Cajun writing in Louisiana. In these and other articles - such as M. Segrest’s essay on Southern lesbian-feminist writers, Sondra O’Neale’s analysis of changing images of black women in fiction, and Jerry Williamson’s discussion of Appalachian writers’ resistance to the imposed identity of “hillbilly” — we see writers struggling with the knowledge that they and their art have been relegated by the literary establishment to “minority” status — in other words, inferior and irrelevant. From such angry and painful struggles, these writers achieve a victorious liberation of identity and purpose.

Festival abounds with such victories. The two stories — Cheryl Hiers’ “A Citizen of Florida” and Barbara Angle’s “Kate” — portray two different women asserting their dignity and courage in hostile environments. The storytelling section celebrates the joy, humor and poignance of oral literature, so vital to the South’s history and yet so fragile in an age of mass communication. In the publishing section, small-press publisher Judy Hogan describes her valiant efforts to publish fiction and poetry when publishing is dominated by corporate conglomerates. Tom Campbell and John Valentine share their experience of running a small, independent bookshop, a kind of store fast disappearing from America in the wake of burgeoning shopping malls and chain bookstores. Other writers, such as George Scarbrough, Alice Walker and Max Steele, discuss the power of writing to reveal and interpret Southern landscapes, both external and internal.

From the beginning, we saw Southern Exposure’s literature issue as being unique. We knew that various surveys of Southern literature had been published in books and journals; but we also knew that most of these examinations focused almost exclusively on the literary text, with an academic audience in mind. We set out with different goals. One was to examine literary activity in the South on many levels, ranging from contemporary fiction and poetry to the teaching of literature in the schools, to the problems of publishing and distributing books. We sought also to strike a healthy balance between first-hand accounts of Southerners’ involvement with creative writing and interpretative essays which put these personal accounts into a larger scholarly and sociological perspective. We envisioned a broad audience, scholar and general reader alike.

Even more important, we wanted this book to celebrate the rich cultural diversity of Southern life and literature. We wanted to emphasize that Southerners are a people who live and write in a variety of ways, using different images and holding different values. Festival invites us to listen to the vivid and fascinating voices of Southern life; to appreciate the insights, wisdom and grace of our neighbors, whose voices may not sound exactly like our own, and to recognize our deeper, common quest for identity and dignity. In these fast-changing times, with television and technology undermining community values and expression, we celebrate our diversity and encourage our creative writers to remain ever vibrant, ever strong.

Tags

Bob Brinkmeyer

Bob Brinkmeyer, a long-time friend of the Institute, teaches English at North Carolina Central University and has published extensively on Southern literature. This summer he hopes to perfect his jump shot and bring up his batting average in City League softball play. (1981)

Stephen March

Stephen March, a West Virginian, has been a piano player in a bar, a photographer, a truck driver, a reporter, a farmer and a spare hand in a cotton mill. He is currently completing a novel. (1977)