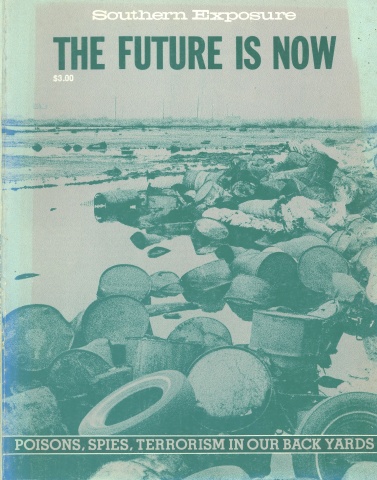

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 3, "The Future is Now: Poisons, Spies, Terrorism in Our Back Yard." Find more from that issue here.

JEFFERSONVILLE, Ga. - Charles “Chess” McCartney is 97 years old. He’s spent almost a third of those years traveling about the country in a trinket-laden wagon pulled by 16 large Angora goats. The “Goatman” — as he’s mostly called — has traveled with his goats to every state in the Union except Hawaii. They’ve even been to Alaska!

The Goatman’s journeys began in the early years of the Great Depression. Through working long hours in the field six days a week, and teaching the Gospel on the seventh, Chess was able to own his own home, some farmland and a church near his parents’ homeplace in middle Georgia. Compared to many of their neighbors, Chess and his family were prosperous.

But the economic crash of 1929 changed their lives completely. Seeing no future in farming, since food was plentiful but money was not, Chess and his family decided to see how the rest of the world was doing.

Leaving their worldly goods behind for those less fortunate, Chess took his wife, son and dog and set off in an old two-stage, iron-wheeled wagon train, with enough food to last them through a long, cold winter. These travels were to last — for the Goatman at least — for over 30 years.

The Goatman, and his family when they were with him, used to walk alongside the billy goats as they pulled his two wagons along the road. The first wagon carried the postcards and novelty trinkets which the Goatman sold along the way. The second wagon, which was hooked onto the first, was where they slept. The nanny goats and the young ones were tied behind it. Some of his goats stayed with their master for as long as 25 years.

A close friend of the Goatman, Hub Gardner, recalls the primitive conditions in which the Goatman thrived. “I’ve been over to Rome, Georgia, delivering cards to him when the snow would be knee-deep. And the only heat he had was a kerosene lantern hanging in the wagon. It burned all night. As I walked up I could see straight through the cracks in the wagon. He stayed on the road winter and summer enjoying it all.”

Maybe due to the lack of competition in his unusual line of work, the Goatman has made plenty of money. He had many shrewd tricks for getting the most for his cards and novelties. One was building a fire near the road out of pieces of old rubber tires. The black smoke would roll up, bringing people running to see what it was.

“Look all you want to, folks.” the Goatman would say. “Take pictures if you have cameras. If not, I have picture postcards for sale, 15 cents each or three for 50 cents.” He says you wouldn’t believe how many people would jump at that offer, thinking they were saving money. He would also preach to his customers out of his ever-handy Bible.

The Goatman invested his money in land, back when land was dirt-cheap and few people, especially in the South, had cash to buy it. He owns one-acre plots all over the United States. The Goatman’s hobby is building churches — five, so far. One is a little log church on an acre of Louisiana swampland.

Life hasn’t always been easy for the Goatman. “My arm was chewed all to pieces where a horse drug me across the road once,” he told me recently, showing me his twisted arm which he can still use very well. “But the only pain I have now at age 97 is where my leg has been slit on both sides and has eight screws in it, where the doctor fixed it up after some teenage boys overturned my wagon with me in it. They also cut the throats of eight of my lead-goats and left them laying dead on the highway.” Soon after this incident, in the early 1960s, the Goatman retired from the road to his homeplace near Jeffersonville.

Four or five years ago, his house there burned down. The Goatman lost most of his shoulder-length hair in escaping from the flames.

Still a traveling man at heart, he now lives in an old school bus near the site of his burned-out house. Like his wagon, the bus has no electricity or other modern conveniences. But the Goatman doesn’t miss them. The postcards and novelties are still selling, and people still come by to visit, buy and listen to his tales of adventure on the road.

To any who have missed him since Ills retirement from his travels, the Goatman would like to say, “I’m still around and kicking, which I hope to be for some years to come. So look me up for a visit or drop me a line. It’s always good to see and hear from old friends.”

- LORENE L. PARKER

freelance

Russellville, Al.

“Facing South” is published each week by the Institute for Southern Studies and will henceforth be a regular feature of Southern Exposure. It currently appears in more than 80 Southern newspapers, magazines and newsletters. If you’d like this fascinating series of Southern profiles - written each week by a different grass-roots Southerner - to appear in your local newspaper, call your editor and tell her or him to write “Facing South,” P.O. Box 531, Durham, NC 2 7702, or call (919) 688-8167. “Facing South” is an ideal feature for community /political newsletters, too. Our rates are based on circulation and start at $3 a week.