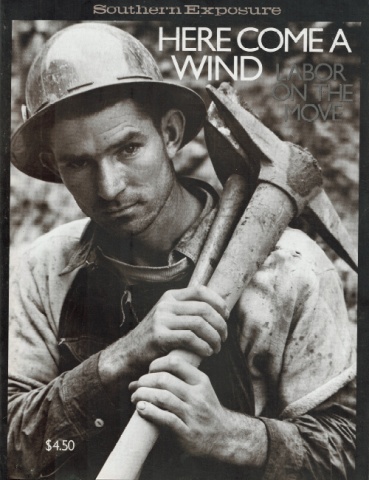

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

Jim Youngdahl, an attorney in Little Rock, has been involved in Southern labor struggles since 1948. He worked for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers (1948-56) before turning to a career in labor law. He has written extensively in both legal and popular journals, and is recognized as an expert in the field of equal employment. He is general counsel of the International Woodworkers and regional counsel to the UAW.

John Stewart is a black man who lives in the country near Dierks, Arkansas. In 1959, he was hired to run a "surfacer" machine at a sawmill in Dierks. He stayed on that job until 1972, when the giant Weyerhaeuser Company, which bought the mill, "modernized" it, bringing in a "matcher" to do the work the surfacer used to do.

John Stewart was denied a chance to work on the matcher at $3.06 per hour, and was demoted from his $2.73 rate to a common labor job of "takedown operator" at $2.23.

On January 7, 1974, Stewart filed a grievance under a special procedure set up by the International Woodworkers of America for discrimination complaints against Weyerhaeuser. "My pay rate was discriminatorily reduced 49c per hour several months ago," he wrote, "and when the Merchandizer and Plywood plants were started up, I was not offered a promotion job."

Because of the IWA's efforts, in April 1975, John Stewart was finally promoted to the matcher job with an 83 cents per hour raise to $3.75. In addition, he received $8,000 backpay plus $1,302.11 for five years of interest and the full cost of presenting his case.

John Stewart's gains were more than usual, but he is only one of 1,500 Southern black and female IWA members who have been awarded over $500,000 backpay under the union's program to enforce the equal employment rules of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Unions traditionally have worked for higher wages, better working conditions, and seniority rights. But recently they have begun to use the equal employment rules as vital tools for correcting the injustices of a prejudiced society. Now tens of thousands of Southern workers like John Stewart have reaped a harvest of promotions, discipline cancellations, fringe payment extensions and other benefits. These successes are the results of the civil rights movement and the labor movement— often supporters of each other, but occasionally enemies — working for the same goals. It is an alliance that can and must remain strong if workers — black and white — are to improve their conditions.

Long Time Coming

Civil rights supporters had fought for a century in support of a ban against job bias before Congress finally passed the equal employment law in 1964. Beginning in the 1930s, rules against discrimination had been issued by the federal executive branch, culminating in Fair Employment Practices (FEP) committees under Presidents Roosevelt and Truman. Federal employees and employees of companies doing business with the government were especially affected; but these original policies had little meaning because they lacked real enforcement procedures.

In 1943, US Congressman Vito Marcantonio, a member of the American Labor Party, introduced

the first bill which would give statutory power to FEP agencies. At every session after that, a variety of equal employment proposals was offered. None approached passage, however, mainly because of the obstacle of Southern Senate filibusters. Although the 1954 school segregation decision and the surging civil rights movement generated helpful legislation in other fields, nothing happened in terms of equal employment.

In 1961, the Kennedy administration added enforcement power to the program concerning employment practices of government contractors. And with the civil rights movement in full swing, a federal equal employment law finally was passed.

Throughout this period, the labor movement, especially the progressive industrial unions, had fought for FEP legislation with money, mass political action and Washington lobbying as a part of the long-term commitment to civil rights. And at the crucial moment, labor participation in the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights helped swing the 1964 vote.

Effective July 2, 1965, it became illegal for. almost all American employers to discriminate as to "compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of. . . race, color, religion, sex, or national origin." One hundred and eighty-nine years after the promise of the Declaration of

Independence, effective national law made employment discrimination illegal.

Under the new legislation, civil rights leaders, unions and employers expected discrimination to be banned in obvious areas like hiring procedures and lunchroom facilities. But the law's general language invited considerable controversy over how other provisions should be applied. For instance, on an important issue, some unions and business¬ men argued that the law allowed them to keep promotion systems based on "departmental" or "job seniority," that is, where promotion was determined by a person's length of employment in the job below, or in the department, where the vacancy occurred. Civil rights advocates contended that such systems were outlawed by the 1964 Act since they "perpetuated the effects of past discrimination": if an employer had discriminated when he hired or assigned a worker, use of departmental or job seniority would continue to block the disadvantaged person from holding more desirable positions.

As in other cases involving the interpretation of civil rights, it was the courts—not the legislators or executives — that decided how the law would affect real life situations. And Southern judges, who had been taking the heat for their rulings for school desegregation, were not about to retreat into conservatism on employment discrimination issues. In cases arising from a tobacco plant in Richmond, Virginia, and a paper mill in Bogalusa, Louisiana, federal judges completely rewrote the standard union-management's seniority language in favor of the civil rights advocates. When they finished, the only promotion systems permitted were those that used "plant-wide seniority" — the time employees worked in the plant regardless of their job position or department — to determine a worker's right to job openings. Thus, in companies where blacks and whites both had been hired over the years, whites would not get preference for vacancies simply because employers originally assigned them to better jobs.

Such drastic changes in the standard for job advancement, inconceivable to all but a handful of creative and courageous civil rights lawyers, were shocking to labor unions. Seniority, the only "credit" for the "investment" of years that workers get, suddenly was undermined not by the traditional enemy across the bargaining table — the boss — but by legal cases coming from the very law which labor unions had strongly supported.

Shock turned to outrage when Southern judges, picked from the business establishments began to assess unions equally with employers for back pay awards. Consider, for example, a sawmill which employs 100 blacks and 100 whites and which assigns the whites to jobs paying $1.00 an hour more than the blacks. In a case over the promotion system where five years of backpay can be recovered, a million dollar award could easily be claimed. If the IWA union is liable for half of that, it would be required to pay $500,000 — twice the amount of all IWA dwindling assets. A loss like this would end the international union.

As salt in very deep wounds, the unions that historically had represented large numbers of blacks, like IWA, were the most subject to financial liability. Unions which blatantly discriminated by keeping blacks out altogether, such as in some building trades, had no serious money problem. They had not made discriminatory promotions only because they hadn't permitted the hiring of blacks at all!

Representatives of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the federal agency set up to process charges of discrimination, were openly anti-union. When workers sought to charge their employer only, the EEOC frequently insisted that the union be added as a defendant. Traditional civil rights organizations, finally finding a vehicle for ending centuries of employment discrimination, had little interest in making distinctions among the guilty parties. Civil rights lawyers, alert to the crises of the 1960s and 1970s but less aware of the structures and struggles of the labor movement, supported these judgments. They often regarded “giant unions" on a par with “giant employers," as purveyors of evil and controllers of money. One lawyer for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, now a prominent EEOC official, told a union lawyer, “Samuel Gompers never did anything for my granddaddy."

The fact that it was the employer's hiring policies which started the discrimination was forgotten. The fact that union dues are used to serve the entire union membership, black and white, not to profit stockholders, was ignored when backpay and attorneys' fees were claimed. In the end, when the civil rights case was over, it fell upon the union to represent all of the workers in day-to-day protection against an employer's discrimination.

Slowly, Southern unions began to understand that plant seniority was an essential bargaining demand for all negotiations. In some cases, union lawyers and civil rights attorneys have joined together, forcing companies to initiate affirmative action programs for minority workers. Equal employment lawsuits have offered opportunities to advance union principles, and the means to avoid the burden of devastating financial judgments. For many unions, the Civil Rights Act finally became a structural tool for positive change and a vehicle for forging coalitions of working people. The efforts of the International Woodworkers of America illustrate the importance of using the law for both reasons.

ONE UNION RESPONDS

For many years, the wood products industry has been the largest industrial employer of blacks in the South. About 27 percent of all black workers in Southern manufacturing are in lumber operations.

The IWA, although the largest union in the industry, has been kept ineffectively small by vicious employer hostility. Until recently, its consequently weak bargaining position had permitted limited success in achieving equality for all workers.

The IWA has 75 collective bargaining relationships in the Southern states, with 17,000 members. Only a few units contain a thousand employees; a couple dozen have several hundred and the rest are small. It has been a long tough battle for the IWA, or any union, to survive in the Southern wood products industry. Yet because it has survived, it could be threatened with bankruptcy from backpay settlements.

Affirmative action, with all its perils, has been the only answer. A few charges were filed against employers as early as 1969, but the main program was launched with International Executive Board action in 1972.

The IWA resolution gives some hint of the practical and political problems involved. The traditional goals of worker equality as well as the present threat of union financial liability were among reasons given for “policies and programs which will seek out and remedy instances of discrimination on the basis of race, sex, and other factors" (see box).

Up to now, IWA lawyers have studied 45 of its 75 Southern collective bargaining relationships. No action has been taken in ten because no serious legal question seems to exist. Fifteen are still being investigated or negotiated. Ten cases have been settled, with the backpay and other changes described above. Ten are in heavy litigation; some employers, such as mammoth Georgia-Pacific, refuse to deal with their equal employment obligations and are fighting the union every step of the way.

John Stewart's employer, Weyerhaeuser, furnishes an example of how the program actually works. Sometime in 1972, just as formal IWA affirmative action was beginning, a small committee of blacks working in a 2,000-employee complex in Dierks sent the company a letter protesting its hiring and promotion practices. A copy went to their union, Local 5-15 of the IWA. Even without specific instructions about such procedures at the time, Local 5-15 President and Business Agent Jim Tudor met with the committee of black workers and offered union assistance to change the discriminatory pattern.

The offer was accepted. Attorneys for the international union were called in, and the entire group met with local Weyerhaeuser management. The response by the complex manager, for two or three meetings, was to name several "boys" who had gotten good jobs, and to give assurance that since he was from the state of Washington, he was not prejudiced. Next, the union filed EEOC charges for itself and on behalf of the black employee committee. The law prescribes that six months must pass before a court suit could be filed. As the time ticked away, word of the dispute finally reached corporate Weyerhaeuser headquarters in Tacoma, Washington. The company pleaded for more time, and, at last, serious negotiations began.

Finally, in the middle of 1973, agreement on all issues was reached. The company agreed to pay $100,000 in backpay, install plant seniority for virtually all promotions, place blacks and females in supervisory positions, establish training opportunities and otherwise obey the developing case law.

Particularly novel, the Weyerhaeuser settlement included the creation of a special grievance procedure. Grievances over past discrimination, such as that involving John Stewart, had to be filed within six months of the agreement. (Unfortunately, in spite of repeated union urging, very few employees took advantage of this opportunity to complain of historic treatment.) Grievances over current issues could be filed within six months of the time they occurred. All costs of the procedure, including lawyer's fees for the worker, would be paid by the employer.

In three years of operation, this grievance procedure has brought good results. About 125 have been filed, half for race discrimination, close to half for sex discrimination and the rest involving national origin. About $25,000 more backpay has been collected, dozens of promotions have been awarded and apologies have been forced from insulting supervisors. The company has paid the full cost of a procedure that provides a ready opportunity for individual expression of dissatisfaction with day-to-day discrimination.

And to illustrate the confidence of workers in their union, the grieving employees have each asked the union officers and lawyers to represent them against Weyerhaeuser, although they could have hired outside spokespersons at no cost. When his case was over, John Stewart wrote his local business agent, "I sincerely want to thank you for the great job you did."

The variety of IWA remedies have been impressive. In Waycross, Ga., maintenance man J. L. Bellamy received a retroactive raise in pay from Champion International and a guarantee that he would receive training to reach the top millwright rate within six months. In Franklin, Va., Union Camp agreed to include among backpay recipients 11 pensioners who retired long before the 1974

IWA settlement, but whose pension checks were based on previous earnings kept low by discrimination.

When Weyerhaeuser admitted that its Mountain Pine, Ark., supervisor used "inappropriate language" and agreed to pay Louise Blevins one day's pay, the supervisor quit. Even management jobs outside the union bargaining unit have figured in IWA cases; Roy O. Martin Co., in Alexandria, La., agreed to hire at least one black for every two supervisory vacancies until the ratio reached the proportion of blacks in the overall labor market. Clearly unions and blacks can work together.

LABOR'S ROAD AHEAD

It cannot be said, however, that organized labor has "seen the light" in anti-discrimination law. A great range of attitudes still exists — from the ringing rhetoric of equality to practical recognition of the necessity of affirmative action, from ignorance of techniques to remedy discrimination to open prejudice. One of the largest unions has spent millions of dollars opposing EEOC actions and still has not learned a lesson. A longshoremen's union is fighting to legal death against court orders to desegregate its locals. Most building trades unions still make miniscule black referrals.

Unions in the industries that were targets of the early "test cases," such as tobacco and paper, have come close to disaster by bearing the brunt of the developing law. The Tobacco Workers Union, for example, had to borrow money from at least one employer to help pay off large backpay judgments, an obligation that will undercut bargaining power for years to come.

But things are moving. The International Union of Electrical Workers has made dramatic strides, for both blacks and women, through affirmative action. The Auto Workers and Steelworkers Unions are trying. The Steelworkers consent decree for basic steel, although attacked from both sides, provides for over $30 million in backpay — the largest single recognition of these legal obligations since the law was passed.

"What affirmative action did for John Stewart is important," IWA President Keith Johnson told the 1976 convention, "and was vital for the survival of our union. But let us not forget what affirmative action for equal employment opportunity is doing for our soul."

The merger of civil rights and labor interests are not always so amiable. In fact, the recession has brought to the forefront a new round of bitter fighting between the old allies over the grotesque question: Who should be laid off first?

Instead of an expanding economy, the total number of jobs began to shrink. Under these circumstances, plant-wide seniority, which satisfactorily answered the question "who should be promoted," became unacceptable to civil rights organizations because it also meant that blacks, as the most recently hired, were the first fired. Was there an alternative standard? Who "rightfully" should be laid-off first: employees with high seniority standing or employees hired under affirmative action programs? Should the white be fired, thereby ignoring the seniority he worked so hard to accumulate? Or should the black go, thereby cancelling progress in eliminating hiring discrimination?

Again tensions arose between civil rights advocates and labor leadership because of the employers' discrimination and power to hire and fire. And again the issue went to the courts with the natural allies on opposing sides. Southern unions, often close to exhaustion after fighting for simple survival against ruthless employers, considered the threat to plant seniority an attack on the last remnant of worker security. Put simply, if unions cannot enforce seniority protection against management's

arbitrary actions, they can no longer serve as effective agents for workers. Civil rights proponents argued with equal force that the "last in, first out" principle undermined the concerted effort to end the cycle of economic discrimination.

In March 1976, the Burger Supreme Court handed down a 5-3 decision casting some light on the legal outcome. The decision (Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.) provides that a worker who was not hired because of race discrimination may, when eventually hired, begin seniority standing from the time of that first rejection. The language of the opinions indicates, however, that blacks or women who were not personally rejected would receive no seniority credit. All sides are now altering their strategies to meet this new framework and to prepare for other expected decisions.

As in the past, the final resolution of this problem will require a new level of creativity and cooperation from civil rights and labor leaders. Clear and unified demands must be put to employers to pay laid-off workers — black or white — until they find equivalent employment. This "severance" pay responsibility should be required where discrimination existed in the past and/or where employers couch layoffs behind the smokescreens of "a bad economy" or "needed automation." If the courts can utilize the law to benefit — and harm — groups of employees, the law can likewise be used to place the burden of layoffs on management. And when the employer is not responsible for the layoffs, the society as a whole should absorb the damages— not the individual worker. Supplementary unemployment benefits, job training programs, and public work jobs are traditional remedies.

But we must move toward longer range goals of restructuring work and job relationships so that one class of workers is not pitted against another. In the final analysis, unions, functioning properly with education and organizing programs, must work to bridge these destructive gaps between black and white Southerners by speaking with a collective voice. From this perspective, equal employment laws offer an important means for unions to serve the special needs of a growing number of black workers while revitalizing the strength of their organization. The opportunity to restore the natural alliances, the true hope for Southern progress, must not be lost.

Tags

James E. Youngdahl

Jim Youngdahl, an attorney in Little Rock, has been involved in Southern labor struggles since 1948. He worked for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers (1948-56) before turning to a career in labor law. He has written extensively in both legal and popular journals, and is recognized as an expert in the field of equal employment. He is general counsel of the International Woodworkers and regional counsel to the UA W.