The Cup Runs Over

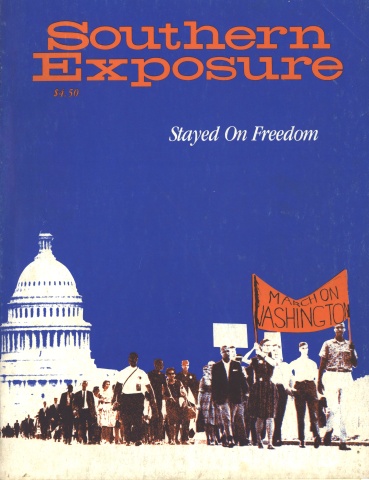

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

Coming from the airport May 6, we drove past the post office and onto Fifth Avenue toward the A.G. Gaston Motel, integration headquarters. Then we saw why the downtown area was “cop-less.” On the roofs of the three- and four-story buildings surrounding Kelly-Ingram Park were clusters of policemen with short-wave radios over their shoulders. At the four intersections surrounding the park were dozens of white-helmeted officers.

With the Birmingham police were reinforcements from such nearby cities as Bessemer, Fairfield and Leeds. Also on hand were deputy sheriffs of Jefferson County and a sprinkling of state troopers. The officers seemed fearful. This fear was expressed in marathon chatter and forced joviality as they waited for the ordeal that was to come: another massive demonstration.

Pressing on each cop were the eyes of 4,000 Negro spectators — women, men, boys, girls and mothers with babies. They were on the porches, lawns, cars and streets surrounding the park. They didn’t talk much, just looked ... and waited.

Frequently both the policemen and Negro spectators turned toward the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. From the more than 3,000 persons inside the church, and 300 pressing toward its doors on the outside — mostly grammar and high school students — came the loud songs of freedom: “We Shall Overcome,” “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Round.”

The temperature hit 90 degrees. Everybody was sweating. “Freedom! Freedom!” A roar arose from the church. Some officers unleashed clubs from their belts. The faces of those I could see had turned crimson. Jeremiah X, Muslim minister from Atlanta standing near me, commented: “At any moment those cops expect 300 years of hate to spew forth from that church.”

“Y’all niggers go on back. We ain’t letting no more get on those steps,” a police captain ordered as I approached the church. I turned away. The time was 1:10 p.m. Four fire engines arrived at the intersections and set themselves up for “business.” Each disgorged its high-pressure hoses, and nozzle mounts were set up in the street. I was to learn the reason for the mounts later, when I watched the powerful water stripping bark off trees and tearing bricks from the walls as the firemen knocked Negroes down.

Before I could get back to the motel the demonstrations began; 60 demonstrators were on their way, marching two abreast, each with a sign bearing an integration slogan. Dick Gregory, the nightclub comedian, was leading the group.

At a signal, 40 policemen converged, sticks in hand. Up drove yellow school buses.

“Do you have a permit to parade?” asked the police captain.

“No,” replied Gregory.

“No, what?” asked the captain in what seemed to be a reminder to Gregory that he had not used a “sir.”

“No. No. A thousand times no,” Gregory replied.

The captain said, “I hereby place you all under arrest for parading without a permit, disturbing the peace and violating the injunction of the Circuit Court of Jefferson County.”

Bedlam broke loose. The young demonstrators began shouting a freedom song. They broke into a fast step that seemed to be a hybrid of the turkey-trot and the twist as they sang to the tune of “The Old Grey Mare:”

“I ain’t scared of your jail

cause I want my freedom!

... want my freedom!”

And for the next two hours this scene was repeated over and over as group after group of students strutted out of the church to the cheers of the spectators, the freedom chants of those being carried away in buses and a continuous banging on the floors and sides of the buses — a cacophony of freedom.

That day, the dogs were kept out of sight. The Birmingham riot tank was on the side street. The fire hoses were kept shut. The police clubs did not flail. The thousands of spectators also kept calm. The police savagery of the preceding week was contained.

Back at the Gaston Motel, there was a joyous air. Leaders in the organizational work, such as Dorothy Cotten, James Bevel and Bernard Lee of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; Isaac Wright, CORE field secretary; and James Forman, William Porter, William Ricks, Eric Rainey and students of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee joined others in the motel parking lot in a parade and song fest.

Victory was suggested by the absence of the dogs, the lack of violence. Added to this was the news that a judge had continued the cases of 40 persons because “there was no room at the inn” for those sentenced. The threat of the Movement to fill the jails had been realized in Birmingham.

Rejoicing was short-lived. At six p.m. word got back to the motel that the 1,000 students arrested earlier had neither been housed nor fed. With Jim Forman of SNCC, I drove to the jail. There were youths throwing candy bars over the fence to the students; spectators had passed the hat to purchase the candy. While we were there it began to rain. The students got soaked. The spectators, too, got wet. There was no shelter for the kids. The cops and their dogs got into the squad cars. They stayed dry.

Forman begged the cops to put the kids inside, in the halls, in the basement of the jail, anywhere. Nothing was done. A new day had not yet come to Birmingham.

That night the weather turned cool. We learned that the students were still in the jail yard, unsheltered and unfed. The same message got to the others in the Negro community. An estimated 500 cars and 1,200 people drove to the jail with blankets and food. The police responded by bringing up dogs and fire hoses. The food and blankets were given to the kids. The crowd waited until all of the children were finally taken inside.

Later that night Forman and Dorothy Cotten of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference met with the student leaders. In the planning, emphasis was placed on the need for speed and mobility. Heretofore the demonstrators seldom got downtown, or if they did, never in a large group. It was decided that instead of starting the demonstrations every day at one p.m., when the fire hoses were in place and the police were all on duty, an element of surprise would be introduced. The next demonstration would begin earlier. Picket signs would be taken downtown to prearranged spots in cars where the students could pick them up.

That night five of us slept in a motel room designed for two. We were crowded, but so were the 2,000 students crammed 75 or more in cells for eight in the city jail. Our room was hot that night, but not so hot as the unventilated sweat boxes in which Cynthia Cook, 15, and other girls were placed as punishment by the jail personnel when they refused to say “sir.” Those on the outside were tired, but not so tired as the hundreds who had been forced to make marathon walks because they sang “We Shall Overcome’” in jail. And there were beatings for many.

At six a.m. Tuesday, SNCC and CORE fellows hurried to the schools to get out the students. Before 10:00 — and before the police lines and firehoses were in place — 600 students had been to the church and been given assignments downtown. Cars were dispatched with picket signs. The clock struck noon. The students struck. Almost simultaneously, eight department stores were picketed.

I was standing near a police motorcycle, and could hear the pandemonium at police headquarters. Police not due to report until after 12:30 were being called frantically. Policemen sped, sirens screaming, from Kelly- 56 Ingram Park to downtown. Inside the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church the folk laughed and sang “We Shall Overcome.”

Over the police radio I heard Bull Connor’s voice. He was mad. He had been betrayed. Never before had the students demonstrated before one p.m. I suspect the merchants were mad. And the kids downtown, all 600 of them, sang “We Shall Overcome.” And they did overcome. No arrests were made. When the police finally got to the area, they merely ripped up the signs and told the youngsters to go home. The jails were full.

For the students, “home” was back to the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. There they were reassigned to go to Woolworth’s and six other department stores, sit on the floor, and not move unless arrested. Since the jails were full, the cops still weren’t arresting. A policeman went to the church to tell somebody from the Movement to ask the students to leave. When the announcement was made in the church, 2,000 persons went downtown. These thousands were joined by 2,000 spectators and made a wild, hilarious parade through downtown Birmingham, singing “We Shall Overcome.”

Then the nearly 4,000 persons returned to the church from the “victory march.” And while the throngs joyously sang inside, preparations were being made outside. The cars with dogs drove up. About 300 police officers surrounded the church and park area. Fire hoses were set up.

For a few minutes I left the area of the church and went to a nearby office. When I emerged I saw 3,000 Negroes encircled in the Kelly-Ingram Park by policemen swinging clubs. The hoses were in action with the pressure wide open. On one side the students were confronted by clubs, on the other by powerful streams of water. The firemen used the hoses to knock down the students. As the streams hit trees, the bark was ripped off. Bricks were torn loose from the walls.

The hoses were directed at everyone with a black skin, demonstrators and non-demonstrators. A stream of water slammed the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth against the church wall, causing internal injuries. Mrs. Colia LaFayette, 25-year-old SNCC field secretary from Selma, Alabama, was knocked down and two hoses were brought to bear on her to wash her along the sidewalk. A youth ran toward the firemen screaming oaths to direct their attention from the sprawling woman.

Meanwhile, over the public address system inside the church, I could hear a speaker admonishing the people to be nonviolent: “We want to redeem the souls of people like Bull Connor.”

I wondered how long it would be before some Negro lost his restraint. It had almost happened Monday, the day before, when cops flung a Negro woman to the ground and two of them had put their knees in her breast and twisted her arm. This was done in the presence of the woman’s 19-year-old son and thousands of Negro spectators. Four 200-pound Negro men barely managed to restrain the son.

That terrible Tuesday, May 7, ended finally. There was much talk about an impending “settlement.” This news discouraged all but the most cursory plans for the next day. Everyone realized the influx of state troopers would make downtown demonstrations difficult.

A strange thing about the demonstrations up until Wednesday was that all of the brutality had been police brutality. Where were the thugs who with razor blades, a few years previously, had cut off the penis of a Negro? Where were the men who stabbed Mrs. Ruby Shuttlesworth when she attempted to enroll her child in the white high school? Where were the whites who repeatedly bombed Birmingham churches and synagogues?

On Wednesday, after almost five weeks of protesting, the non-uniformed racists had not spoken. On May 12, Mother’s Day, they spoke . . . and the cup of nonviolence of Birmingham Negroes overflowed. America learned that the patience of 100 years is not inexhaustible. It is exhausted.

Leaders of SCLC and the white merchants agreed on May 10 to adopt a plan to end segregation at selected lunch counters in Birmingham. The next day, “Bull” Connor urged white racists to boycott stores which agreed to integrate. That evening, white terrorists struck with a series of bombings. On May 12, a rebellion involving several thousand blacks occurred, causing damage to property in the millions of dollars.

Tags

Len Holt

Len Holt is a Movement lawyer who wrote this article in 1963 while he was a National Lawyers Guild observer of the Southern Freedom Movement. (1981)