William Darity on the COVID-19 pandemic, racial inequality, and reparations

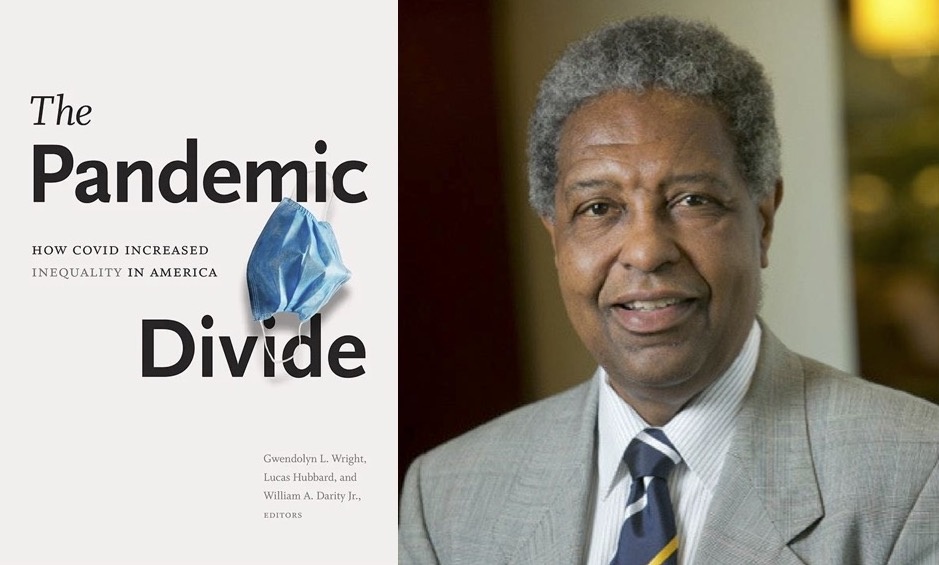

William "Sandy" Darity, economist and co-editor of "The Pandemic Divide: How COVID Increased Inequality in America," said that eliminating the racial wealth gap through reparations for Black Americans could have lessened the devastating effects of the pandemic. (Photos via Duke University Press and Duke University.)

The coronavirus pandemic exacerbated racial inequality in the United States. COVID-19 has killed over one million people to date nationwide, but it did not affect all communities equally. Native American people died from COVID at 2.1 times the rate of white people, while Hispanic people were 1.8 times and Black people 1.7 times more likely than whites to die, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Though a Washington Post analysis found that COVID mortality rates for white Americans surpassed that of their Black and Latino counterparts last fall, the heavy toll of the early pandemic on communities of color came with not only the everyday burdens of systemic racism but new forms of it that arise in a public health crisis.

For instance, people of color were overrepresented in frontline industries as "essential workers" who did not have the privilege of working remotely, thus putting them and their loved ones at risk of contracting a deadly virus in order to simply survive. Meanwhile, Asian Americans faced an onslaught of harassment and violence throughout the pandemic, the result of a racist narrative promoted by former President Donald Trump that blamed the spread of COVID-19 on China.

A new book edited by scholars at Duke University's Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Racial Equity examines how this country's foundational racial inequality was worsened by the pandemic, while offering policy solutions to lessen the disparities. Titled "The Pandemic Divide: How COVID Increased Inequality in America," it was co-edited by the center's director, Duke public policy professor William A. "Sandy" Darity Jr.; research scientist Gwendolyn Wright; and research associate Lucas Hubbard.

The book includes chapters by leading scholars looking at COVID in relationship to topics such as Black American labor history, housing market inequality, and educational access. Darity, an economist, is among the foremost scholars of reparations for slavery, and not surprisingly reparations are among the policy solutions discussed in the book.

Facing South recently caught up with Darity to talk more about reparations in post-COVID America. This interview has been edited for clarity.

In one of the chapters in your new book about COVID-19 and inequality, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill public policy professor Fenaba Addo and Cook Center research associate Adam Hollowell discuss the idea of a federal jobs guarantee. How would a federal jobs guarantee lessen discrimination against Black and Brown workers?

It wouldn't have a direct effect on discrimination, but it would provide individuals who are adversely affected by discriminatory exclusion to be assured of having employment opportunities. There could be an indirect effect on discrimination in the following way: The existence of a federal jobs guarantee would ensure we have permanent full employment in the U.S., which creates tighter labor market conditions. The tighter the labor market conditions, the more difficult it is for employers to hire people. That has a corrosive effect on the degree of discrimination that they exercise. Then it becomes harder for them to exclude workers on the basis of race if they are more desperate to find workers. So, under conditions of full employment, we ensure we have a comparatively tighter jobs market.

In the 2020 book you co-wrote with your spouse, folklorist A. Kirsten Mullen, titled “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century,” you called for reparations to close the racial wealth gap. Could reparations for Black Americans also serve as a public health tool? How so?

If we had had reparations in place in a form that eliminated the racial wealth gap prior to the crisis, then we would have had very different expectations about the impact of the crisis on racial grounds. There's a study in which [Harvard clinical fellow] Dr. Kathryn Himmelstein demonstrated that the mortality differential that existed prior to the pandemic would have been erased had there been no wealth gap. There's another study that was led by Eugene Richardson at Harvard, and it demonstrates that the contagion rate from the disease COVID-19 all across the entire population could have been reduced by 31 to 68% had we eliminated the racial wealth gap before the onset of the pandemic. If anything, the onset of the pandemic reinforced the case for reparations, because they would improve the capacity of individuals who are being subjected to the deprivations associated with the crisis.

U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, Democrat of Texas, re-introduced perennial legislation last year to study reparations proposals. What's your take on this bill?

The issue is not the creation of a commission. It's been done in the past. A clear example is the Japanese American reparations program, which was preceded by a commission that attempted to establish the case for reparations, as well as design a proposal for reparations. The issue is what type of commission the law will produce. The law that is currently written is not going to produce a commission that would be satisfactory from my standpoint.

The legislation does not provide any directives to the commission on the content of proposals to bring to Congress. The commission should not be given a tabula rasa. At minimum it should be charged with the design of a proposal or proposals that meet four conditions. One, eligible recipients should be designated specifically as Black Americans whose ancestors were enslaved in the United States. Two, the plan must be designed to eliminate the racial wealth gap by raising Black assets sufficiently to bring average Black net worth on a par with average white net worth. Three, the plan must make the federal government responsible for funding the project. Four, the plan must prioritize direct payments to eligible recipients as the form in which reparations will be distributed. The current legislation imposed no constraints on the commission's decisions.

There have been some local reparations efforts in recent years, such as the creation of a commission in Asheville, North Carolina, to allocate over $2 million for reparations. What do you think about these piecemeal approaches to reparations?

Given the fact that you've chosen the term "piecemeal," you're probably familiar with my position already. [Laughs.] I think that this is a detour from forming the type of coalition that would effectively pressure Congress into adopting a full-scale, comprehensive reparations plan. And it's a detour in part because states and localities simply do not have the wherewithal to meet the expenses that would be required to eliminate the racial wealth gap. They just can't do that. Our most recent estimates are that at minimum it would require about $14 trillion to eliminate the racial wealth gap, and the entire budget for all states and localities in the United States is less than $5 trillion. When municipalities set up these programs where they're going to give people $20,000, $25,000, it's not necessarily a bad thing, but they should not try to claim that this is going to have any type of significant effect on the racial wealth differential.

There's significant conservative hostility toward reparations, which we've seen for example in the right's successful effort to block targeted aid for Black farmers despite the long history of overt discrimination they've faced. Given today's contentious political climate, how do we build support for reparations?

I certainly don't have an expectation that the existing Congress would pass a reparations plan. That's why it's essential to have a national movement that would in part alter the composition of Congress. If we can alter the composition of Congress, it might also be possible for Congress to take steps to alter the composition of the Supreme Court, by changing the number of justices. All of these things are things that would require a strong and dedicated political effort at the national level. That's another reason why I'm fearful of any kind of dilution of that effort by focusing on these piecemeal, local initiatives.

But yeah, it's going to require a very strong effort. My reason for having some sense of optimism about these possibilities is because of the strong change in attitude and opinion about Black reparations on the part of white Americans. In the year 2000, a study that was conducted by Michael Dawson and Rovana Popoff at the University of Chicago indicated that only 4% of white Americans endorsed monetary payments as reparations for Black Americans. By the year 2016, that figure had risen to about 15%. Today it is closer to 30%. I don't know if that change in attitude is sustainable, but it certainly creates a foundation for trying to build a movement.

Tags

Elisha Brown

Elisha Brown is a staff writer at Facing South and a former Julian Bond Fellow. She previously worked as a news assistant at The New York Times, and her reporting has appeared in The Daily Beast, The Atlantic, and Vox.