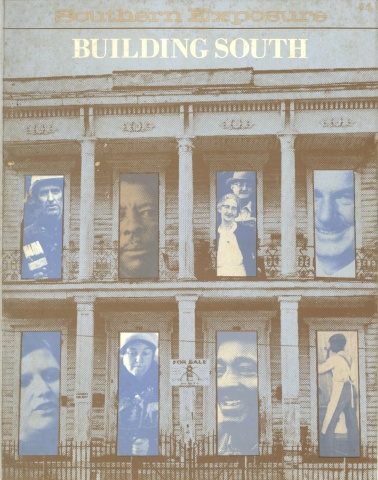

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 1, "Building South." Find more from that issue here.

From Winona, once a town

at the head of Keeney’s Creek,

past the stone columned building, once a bank,

and past the houses of the camp long since

abandoned,

a track bed stripped of tie and rail

switchbacks down the wall of the Gorge.

A branch line pulled by corporate decision

and the sheer weight of taxes

left this one lane trail of rock and sand

where we descend, four in a jeep, laughing

through tunnels of the colors of autumn

to the main line of the C & 0

along a hundred million years of river run.

Our guide leaves off his old jokes and reads

this history from a book:

The completion of the lines was

celebrated on January 2, 1873,

at Hawk’s Nest. In that same

year Joseph Lawton Beury’s small

mine at Quinnimont shipped the

first coal from the New River Field.

The book passed around, and the dusty photographs

let us in briefly

to see the air heavy with soot and the timber

clear cut to the naked cliff walls.

And we see how

in the history of industry Beury’s memory

is fixed in stone

at Quinnimont overlooking the rapids.

Here in the river camps nothing remains

except these houses in the shadow of the cliffs

and pilings of a footbridge

that crossed the river to the Red Ash Mine.

“What’s that up ahead?”

“Looks like someone walking the tracks.”

We follow our guide

as the noon sun beats the distant rails

to rubbery incandescence. We come upon

the beehive coking ovens’ crumbling brick.

“People lived in them

in the thirties, whole families. Saw one even

had a piano in it.”

Off in the distance

an old woman watches us, then moves on slowly,

a large bundle on her back.

“Who is she?”

“What’s she doing there?”

“It’s Melsina. She’s just goin down to Thurmond.

Carries all her belongings on her back. She

worked in the old Beury mansion. Stayed on there

by herself when they closed it up. Train crews

look out for her. Sometimes you see her carrying

an old stray dog like a baby.”

We watch her movement fade into haze

toward Thurmond,

Believe It or Not City, three times in Ripley,

the town with a railroad for main street.

“Not much there now.”

We turn back, walking north, listening

to its tales.

“. . . had the finest hotels, and I can remember

the bar, the whiskey stacked behind the bar,

and the big one dollar slot machines giving

them silver dollars,

and the gambling tables lined with velvet . . .”

We pass under the old Nuttalburg coal conveyor —

“I seen five thousand dollars change hands

in a game of poker . . .”

coming off the cliffs five hundred feet up.

“. . . professionals coming in from the cities is

what finally broke it up.”

Still owned by Henry Ford.

“First steel tipple on New River,” our guide says.

Now rusting away, wooden steps already gone,

no way up to the controls.

“Shut down after the War and left it all.”

The miners recycled the rest of the camp, took

the architecture elsewhere for re-use.

“Look at this!”

(at the stone foundations of the camp church)

“The operators would always build a church,

to have a place to give the dead miners

a funeral in.”

“Yes, and what about the preachers? There never

was a shortage of preachers.”

“You’ve heard about the Yellow Dog, Pete?”

We head back for the jeep, at Caperton camp.

“I seen it put into effect, there

across the river —

old man Collins brought in Baldwin-Felts men;

they put a machine gun

and a searchlight

on the tipple overlooking the camp.”

At Caperton

we rest on steps of a big double house,

admiring the carpenter’s work, everything

done by hand,

neatly trimmed, a little something extra for

the section bosses.

Here the tipple is gone, no sign of the mine.

One question leads to another, and one exclaims,

“Low coal! Lord,

I loaded coal in nineteen inches, where you had

to lay on your side,

and if you had a little lump like that, you had

to beat it up before you could get it

into your car.”

And what follows is talk of pickwork and scabwork

and fixing track and being blackballed with

the Union in ’21.

How you had to be strong as a bristleback,

and our guide says, yes, he worked with a fellow

that had one arm off, had just a short stub,

called him “Wing,”

one of the best coal loaders there was.

And play the piano, why after meetings they

would ask him

and Wing would take that stub and hit the bass

notes and rock back and forth and make the best

bass run you ever heard.

And he had a by-word, he used to say, “John Brown.”

He’d say, “John Brown, I love workin’.”

And the yarns spin

until the dead and scattered faces that lived

here once call in a rush of memory that

leaves us restless,

and standing we see houses, no more than

rotting shells on the hill behind us,

the warm sun softening their sunken roofs.

“An old man lived

here for a while on Social Security checks.”

We walk past a shack on a carpet of lilies

growing in the yard.

Brick chimney torn down, rusting washbuckets

strewn about, and what must have been his

bed frame and springs outside the door, as

though he’s slept out under the stars.

Then in the jeep,

grinding the trail back across the tressels

of steel over waterfalls,

past thick stone walls, laid by hand,

following the switchbacks,

old railroad warning ropes still hanging,

to the miserable remains of life at the rim,

the hollow there

a rut filled with cans, bottles and old tires,

the unpainted houses a story of discipline and

a generation’s pain,

of an extraction that gave next to nothing

in return — here a serenity of decay in wilderness

which comes back lush

and strangles what remains like a tourniquet

on a wound.

We drive home in silence, remembering the labor

of the dead, coal fires that burned at night,

and this rubble left behind.

On September 8, 1901 a railroad construction crew blasted the sandstone cliffs on the south side of New River, opposite Thurmond. When the smoke cleared, there was a perfect profile of President McKinley formed on the cliff. The startled laborers, mostly Italian, fell to their knees, crossed themselves, and cried, "Holy Mother!" That afternoon word was received that the President had been shot in Buffalo, New York.

Tags

P.J. Laska

P.J. Laska was raised and still lives in the West Virginia coal fields. His third collection of poems, Wages and Dreams, will be published in the spring of 1980 by Mountaineer Freedom Press, Box 5, Pipestem, WV 25979. (1980)