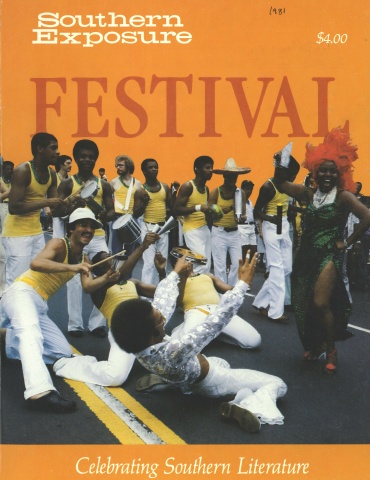

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

Until I was 10, there was nothing peculiar about a woman wearing a hat to church — for weddings, funerals or Sunday services. Then someone somewhere decided hats were out. That news, I’m sure, took awhile to reach our small coastal town, and more time to be mulled over and debated by the ladies of the town. Those concerned were astonished that anyone would invent such a notion. Why would one want to go hatless to church? Nevertheless, one Sunday a few young women suddenly turned up bare-headed at First Baptist. Their hair, having been rolled tight at Marlene’s the day before, popped out boldly in tiny corkscrew curls.

No one said a word.

The next week more young women dared the Inner Sanctum without head cover and, for all I could tell, without the least bit of embarrassment. The wives and older women shot glares at them, but gradually, Sunday by Sunday, they too succumbed to the new style.

Clinging to tradition reveals one’s age, I guess they reasoned. Which in a way was true: by the time I was 12 only the really elderly ladies stuck to their millinery, fashion or no fashion. Yet even those traditionalists observed the old order only in so far as their trips to church demanded. The rest of the week they displayed scalp to the sun and sky, just as their less-modest counterparts ventured to do even on the Sabbath.

There was one woman, however, whose reputation was known to nearly all in our town because of her unique stance on the hat issue. The beach lifeguards, the citrus growers, the farmers and even some of the tourists were familiar with Mrs. Hannah Avant’s name. She was an old real estate lady. No one had ever seen her without a hat on her head — whether in sunshine, rain, lightning storms or high winds. Once during Hurricane Deborah, a city electric man reported Mrs. Avant chasing her cat around the yard, one hand stretched forth tempting the feline with a shrimp while she pleaded, “Kitty, kitty, here kitty,” and the other hand pinning her hat on her head to spite the gale.

Why would Mrs. Avant persevere to keep her head shaded even in a hurricane? People in the town proposed various theories, some plausible, some far-fetched.

The “old dog, no new tricks” argument maintained that Mrs. Avant was brought up like a lady and was too old to change her ways. And since, in her time, ladies would as soon appear in public stark naked as without their hats, she still wore a hat 60 years later despite fluctuations in fashion.

Then there was the “vanity, vanity, all is vanity” assessment that claimed Mrs. Avant had suffered scarlet fever as a child and lost a great patch of hair on the top of her skull. Hats protected the bald spot from the sun and, more importantly, protected her pride.

The “in memoriam” opinion, an unlikely explanation I believe, averred that Mrs. Avant’s father had boasted a head of wavy hair of which he was immoderately proud. Everyone warned him time and again to wear a hat when out in the fields (he was one of the first Samsula farmers), but he suspected a hat would press his hair down and maybe even cause it to fall out. So one heat-killing July day while heaving watermelons on a wagon, Mrs. Avant’s father glanced up to see the “bear stalking the field.” The bear caught him before he knew it, and he fell over dead. Mrs. Avant from that day on, some people will swear, wore a hat in memory of her father and his dear head of black hair which no one in this world will see again. But it seems to me that a hat would be a tactless way of remembering a loved one who by his own stubborn refusal to wear such an article possibly brought about his own death. As I said, though, there are some who will swear by this version and some who will swear by the others.

Mrs. Avant had been an old woman for 20 years when hats became passé. That she still kept up the custom awoke people to the reality of her age and led some of them to forgive her somewhat for her personality. But her active role as a real estate agent, her reputed wealth, her stinginess and, later, her unpopular position on a community matter tended to make people forget she was tipping 80. Most didn’t mind spreading a little gossip about the old lady, or taking in a little.

I grew up among the speculations over her hats and the rumors of her riches. Fortunately or not, I also grew up among pretty regular sightings of Mrs. Avant herself. She lived alone on a white sandy road not far from my own house. The road was called South River Drive and was hell to ride a bicycle on. Twenty feet down it, the sand would shoot out beneath your tires like a magician’s tablecloth and leave you without traction or any hope of pedaling on. The road ran for just one block along Indian River, then turned abruptly in corners at both ends. Beyond each corner mangrove swamps bushed out — giving South River Drive and Mrs. Avant’s large wooden house the appearance of a way-station hacked out of the wilderness. In the river before the house stood a private pier with a “keep off’ sign and a boat ramp Mrs. Avant never used herself since she didn’t own a boat. Except for her river-house which faced westward over the pier and water, her block of land was undeveloped. A biologist, my father once said, could study all the stages of forestation by just visiting Mrs. Avant’s place. Marsh grass sprouted in one section; cedars grew in another spot, and pines in yet another. And finally, reigning at the heart of the estate were the kings — the giant live oaks. Mrs. Avant owned them all and the whole city block of land beneath them.

Every day for two years my brother and I had to plow our bicycles through the sand of South River Drive to deliver a newspaper to Mrs. Avant. Sometimes we’d catch glimpses of her early in the morning squirting water on her hibiscus bushes. She’d stand tall, slightly humped at the shoulders, but thick and imperturbable as a bridge piling. Her head supported an enormous black sun hat so massive you’d think it would tip her balance. A fine arc of water sprayed out from the hose in her hand and refracted the morning sunlight into a shifting rainbow that moved as we moved. The sight impressed us. But we learned to pass it as rapidly as we could, which wasn’t rapid enough considering we had to walk our bicycles, not ride them.

My brother would argue with much conviction that Mrs. Avant despised children — an opinion he picked up from local gossip that was not unsupported by Mrs. Avant’s actions. She spoke out vehemently against new school taxes and, on the personal plane, she refused to recognize my brother’s and my existence. When we walked by, clearly in sight, she wouldn’t say “hello,” turn her head or even flick the stream of water slightly out of its sun-catching arc. And we could never approach her for our paper money: she would leave it in her mailbox at the end of the driveway — it was always the exact amount wadded in a pale green envelope and secured tightly with one of our own red rubberbands. She never left a tip.

Mrs. Avant wasn’t lacking in sentiment; she just preferred not to dilute it in everyday discourse, I guess. She channelled an almost insane energy into keeping up her property and her cats. At least once a year, she summoned Mr. Wheeler to clean the Spanish moss out of the oaks and check the trunks and limbs for diseases. She mowed the grass herself, clipped the hedges and raked her sand driveway. Her hibiscus were tended so assiduously the blooms could have won “Best of Show” in the town’s flower contest, if she had chosen to enter them. Cats were apparently the only creature she allowed herself a fondness for, and her fondness approached madness. She’d risk her life — as she did in Deborah — just to save one’s life.

We all have a yearning to last longer than our bones; people just go about trying in different ways. And when a truly odd way emerges, it’s hard to recognize or hard to accept. I suppose that’s why Mrs. Avant was considered merely a stingy old widow who wouldn’t douse you with her garden hose if you were on fire. We couldn’t see at the time that she had a goal beyond the aggrandizement of land and fortune. Not that a purpose redeems her. But part of her infamous meanness stemmed, I believe, from an intolerance for diversions that might tempt her off the track of what she really held dear.

Towards the end of our paper-route days there was a lot of grumbling we heard from door-to-door and around the town about Mrs. Avant owning half the beachside and refusing to sell the choicest lots until the prices skyrocketed. At 79 she was acting like she still had a fortune to amass for later. My brother and I resigned from the newspaper business after 25 months of loyal duty, right after the New Year and Christmas tips rolled in. We didn’t see Mrs. Avant on a regular basis anymore. But two or three times a week, I’d walk down South River Drive to watch the shrimp boats go by or see the sunset. Occasionally, I’d see Mrs. Avant out sprinkling her hibiscus bushes or mowing her lawn. She’d ignore me as always.

One day when I walked by, she wasn’t in sight, but a white pickup truck was parked out front of her house. Two men sitting inside got out when they saw me. As I approached I read the title “Turnbull Trailer Park” stenciled on the truck door.

“You live around here?” they asked cheerfully.

“A couple of blocks over,” I said.

“Know who owns this land?”

“Mrs. Avant,” I answered. “Mrs. Hannah Avant. She owns the whole block.”

“Think she’d be interested in selling it?”

“What for?” I asked suspiciously.

“We might be needin some more land,” one of them explained.

“Well, Mrs. Avant would never sell this land,” I replied earnestly.

“Even for a good price?”

“No! Not Mrs. Avant. This is her home. It’d be like selling one of her cats.”

The men smiled at each other and climbed back in their truck. The one driving asked one more question.

“This Mrs. Avant an old lady?” he said.

“Yes. She’s real old. She’s nearly —” I began but stopped because the man finished it himself. “She’s nearly 85, right?” he said.

“Yes. I think so.”

“Well, she can’t last much longer,” he declared and drove off. I stood in their dust cloud thinking what an ugly plot they had implied and how I would hate to see trailer homes pulled in under those oaks.

Then something moved over at the side of Mrs. Avant’s house. One of the hibiscus bushes seemed to be shivering. Bravely, I edged right into the yard. Maybe it was a cat or a raccoon....

Then the branches parted and the grinning face of Mrs. Avant emerged between two tangerine-colored hibiscus blooms.

“Hee, hee,” she laughed and the lids of one of her trout-blue eyes bunched together. Not until she had disappeared inside her house did I realize she had winked at me.

The men from Turnbull Trailer Park had to settle for something else. They finally landed the deeds to the man grove swamps beyond either end of South River Drive. They didn’t erect trailers double-wide with porches, but a subdivision stamped out in uniform little yards was constructed on the north side, and there was rumor of a condominium planned for the south end.

Mrs. Avant may have been pestered by more land sharks after that (probably was, since her piece was in a prime location — halfway between the two bridges spanning the mainland and the beachside), but I didn’t hear of anything else concerning her block until my senior year in high school. Then it was a very nasty business and Mrs. Avant’s name suffered a lot of ill use. The county had been growing and the school board decided the beachside needed a new elementary school. But there was the problem of the site. One of the board members knew of Mrs. Avant’s block (but, as it came out later, he didn’t know Mrs. Avant) and suggested an offer be made — not for the entire block, but just one corner of it. A formal letter of inquiry was sent to Mrs. Avant. Six weeks later there had been no answer and another letter was sent, asking for some response “as soon as was convenient.” Mrs. Avant replied this time, informing the school board briefly that the place was not for sale.

The other potential sites had fallen through one by one so by the time the school board received Mrs. Avant’s rejection, they were desperate. Some members suggested the matter be dropped, but one or two encouraged the superintendent himself to make a personal request.

“After all,” they reasoned, “it is the ideal location.”

So one Sunday afternoon the county school superintendent drove out to pay a visit to the one resident of South River Drive.

We wouldn’t know what happened during that exchange except for the fact that this particular superintendent was, as my father put it, “a pompous pontificator” — a man keenly susceptible to the slimmest hint of insult to his person or position. He reported his version of the interview to all the county newspapers for “personal and public vindication.”

The superintendent claimed he had cordially invited Mrs. Avant to reconsider selling “just a corner” of her land. Mrs. Avant replied obdurately that she had no intention of selling. The superintendent pressed her gently — reminding her, as he said, of “the great service she’d be doing the children of the community — the future leaders of our state and nation.”

Mrs. Avant seemed to soften at that idea, and confessed that she didn’t want to sell any part of the land unless she sold the whole block.

At this possible breakthrough, and believing Mrs. Avant was at last ready to negotiate, the superintendent expressed interest in buying the whole block, if the price were reasonable. He knew the school board could always use the land in one way or another. There was already talk of a new county media center, and land would be needed. So he inquired how much Mrs. Avant would consider selling for.

The old woman told him the price for the entire block was seven million dollars.

The superintendent chuckled and exclaimed, catching what he thought to be her humorous mood, “Why, that’s a steal!”

“I know it is,” Mrs. Avant said sternly. “But that’s the price.”

He realized then that she was serious. That she had baited him up to the end to demonstrate her contempt for him as a public servant and for the public he represented.

He left in a state of what he termed “shock at the appalling lack of civic consciousness in some citizens.” Moreover, “it was shameful that a professional like Mrs. Hannah Avant would denigrate her profession and her character by stooping to play cat-and-mouse games with the superintendent of public schools in Coronado County!”

All the papers but one ran the superintendent’s editorial and the daily even published an editorial cartoon on the subject. It pictured an unmistakable Mrs. Avant peering out from beneath an umbrella-sized hat. She sat at a toll booth with an open palm stretched toward a small child. Behind her a county school house was drawn. The caption read, “Seven million dollars, please.”

You’d think other parts of the county wouldn’t be that intrigued by what one woman in one small town did or didn’t say to the school superintendent on a Sunday afternoon in May. But political issues must have been scarce that spring, or else the cartoon irritated in just the right way, for letters rushed into the daily newspaper from all points, rural and urban. The editor of one weekly paper announced after the second week that letters on the “Avant matter” ran three to one against her.

“I agree whole-heartedly with the superintendent,” one reader wrote. “The upper crust should force themselves to consider the plight of others in the world. . .”

“Why didn’t she say ‘no’ and let it go at that?” a puzzled resident of the county seat inquired.

“The rich are always arrogant. . .,” one man pronounced.

“Considering Mrs. Hannah Avant’s long-standing war against raising school millage rates, it’s no wonder she has taken another opportunity to display her antipathy to quality education,” the junior high school principal explained. “The wonder is that the school board would consider asking her for anything, even the price of her land. . . .”

“At least she could have been courteous. . . ,” a woman suggested.

A few letters expressed some support for Mrs. Avant, although in the end I suspect they only aroused more hard feelings.

The wife of the Methodist preacher reminded us that “it is no crime not to sell one’s land.” She exposed herself and her husband to quite a bit of criticism when she went on to say that “Mrs. Hannah Avant is one of our oldest citizens and should be respected for the stringent requirements she exacts from contractors who do buy her lots. . . . She has done more to conserve our land,” the lady continued, “than the State Department of Natural Resources, and certainly more than the city council — a group which has proven itself by its recent zoning laws to be mere sycophants of Northern contractors. . . .” She finished up by chiding the school board for its last-minute planning. “Besides,” she queried, “who is the school board to think it can have the best block on the beachside simply because it wants it?”

This letter prompted counter-responses from several organizations and individuals, including the Rotary Club, the PTA, the Garden Club, a local contractor, an unemployed laborer and a retired colonel.

The contractor wanted to know “exactly how Mrs. Avant had conserved land . . . and if her efforts to stifle the local economy with unreasonable building restrictions was conservation, was it worth it?” A construction worker then unemployed added his signature.

The PTA reiterated its support for the school board and the superintendent in “their tireless efforts to locate a site for the urgently needed school. . ..” They also wanted to remind some of the town residents that the school board had “only the interests of our children in mind. . . .”

The Garden Club spoke up for the State Department of Natural Resources which had “recently allocated generous funds for new roadside parks, complete with picnic tables and port-a-lets. . ..” The Rotary Club defended the city council — “some of whose members were high-ranking officers in Rotary and sorely hurt by the letter intimating wrongdoing on their parts. . . .”

The retired colonel informed the community that he, too, “was one of the oldest citizens of the town,” but he didn’t use his age “as an excuse for displaying rudeness to public officials.”

All this went on for a while and would have perhaps dragged on longer if some of our high school graduation antics hadn’t gotten out of hand. Every year there would be pranks — mostly harmless, funny tricks. The year my brother graduated, a live chicken got deposited in the principal’s office one Friday evening and wasn’t discovered until Monday morning. A Volkswagen was disassembled and rebuilt on top of the gym roof. An alligator turned up snapping on the front lawn before the administration wing. Almost as a rule, the pranks centered about the school grounds, except for the ubiquitous spray-paint boasts that read “class of such-and-such-a-year rules.” My year, however, the “Avant matter” occurring when it did inspired some Samsula farm boys to carry their pranks out to the citizenry — to Mrs. Avant’s place and beyond the limits of mere fun.

When the news broke, it wasn’t in the editorial column. The Sunday morning of our baccalaureate the police received a call from Mrs. Avant requesting that an officer drive out to her house.

She was found standing quietly by one of her huge oak trees, the black sunbonnet on her head.

The officer, a brother-in-law of Mr. Wheeler, asked what the problem was and she pointed to the tree. A white ragged line two inches wide circled all the way around the trunk about a foot up from the ground.

“It’s been girdled,” the officer said. Mrs. Avant nodded her head and asked him to file a report. She would prosecute.

He obtained what information he could from her and assured her the police would do all they were able. But he didn’t expect much in the way of results. High school students probably, but hard to prove. He was sorry ... he knew those trees didn’t grow up over night.

Before he left, Mrs. Avant asked him to tell Mr. Wheeler she’d like for him to come out the next day, with his saw.

“Do you mean to cut it down?” the officer asked. “It might not die. You should wait and see.”

“It’s already dying,” Mrs. Avant answered. “When you do that to it, it has no choice but to die. Can’t get any water, you know that, Mr. Ezell.”

The story got spread about by Mr. Ezell and Mr. Wheeler and their wives.

Our high school principal, like Officer Ezell, suspected some students of the crime. He called a special assembly for the graduates and reproached us all, but most of us felt lousy about the whole thing anyway. In fact, town sentiment seemed to swing that week to Mrs. Avant’s favor. The matter with the school board didn’t pop up once in the papers until Friday. Then, at last, Mrs. Avant wrote a letter in her own behalf.

Not a word about the tree. The letter consisted of one sentence, and it didn’t do a lot to promote the tenuous good will the town had started to feel for Mrs. Avant since her oak was killed.

She wrote, “It is my land and I will do [here the editor inserted four asterisks] well what I please with it.” She signed it, “Hannah Leslie Baker Avant.”

The summer passed quietly. Mr. Ezell was right — the police never turned up the vandals and gradually the matter was forgotten.

September came and I left for college up North. Mrs. Avant dropped from my thoughts, but not completely. Whenever I pined for home, the beach and warm weather, sooner or later the image of Mrs. Avant peeping out between those tangerine blossoms would pop before me and I’d wonder if she were still around.

On holidays home, I would always walk at least once down the road to her place to check if things had changed. They hadn’t. The house might have a new coat of paint. A cat I didn’t recognize might dash across the yard. But nothing much else would be altered.

Towards the end of February of my junior year, I received a letter from my mother informing me, along with the news that “spring has arrived here” and my father “has planted his garden peas,” that “Mrs. Avant has died of pneumonia.”

I arrived home in June and my mother elaborated.

“Mrs. Avant died in her own bed,” she said. “She hired a nurse so she could go home.”

“Who got the land?” I asked.

“The state.”

“No,” I groaned. Mrs. Avant left no children, but I had hoped she might have some relatives that would carry on. But if the state had acquired it, no telling what would be done with it. A public auction probably.

“It’s not like that,” my mother assured me. “She fixed it up so legally tight that the land can’t be touched without an act of Congress, and even then, I doubt they could change it.” She paused and smiled.

“Well?” I pressed.

“She willed that block and the house to the Florida Historical Society. All of her other property and assets are being sold to put into a fund to keep the house and those cats,” my mother stopped and chuckled, “and all the progeny of those cats. In perpetuity.”

“What about the house?”

“To be kept like it is. The Historical Society is to manage it as a museum.”

I started laughing, too.

“She spited the school board with her last breath,” I said. Then something occurred to me.

“Is she buried there?” I asked.

“Not buried. She requested a cremation and the ashes to be thrown from the end of the pier onto the river.”

My walk to Mrs. Avant’s the next day happened to coincide with a field trip excursion by local school children. They stood in a crowd before the front door, stamping little sandaled feet and twitching while a young woman I had never seen before lectured them on what they were visiting. Here and there indifferent cats lay dozing.

I moved up to hear the woman’s words.

“And that,” she announced proudly, “is the Intracoastal Waterway. It starts way up in the state of New Jersey and comes all the way down the East Coast, passes here and goes on to the tip of Florida. This part’s called the Indian River because long ago Indians lived here.”

A boy raised his hand.

“Yes,” the woman said. “You have a question?”

“Indians don’t have houses,” he said defiantly. Some of the other children snickered.

“I didn’t mean the Indians lived in this house,” the woman explained. “It’s been built since their time, but even so, it’s very old. The trees you are standing under were probably here when the Indians lived.”

The children turned their heads back to peer with respect at the over-hanging limbs. I strolled away then, attracted by an open space in the network of branches and leaves. I found a tree stump as I expected. Its diameter must have been five feet or so. In the center a small plaque had been bolted. It read:

THIS HOUSE AND THIS LAND IS BEQUEATHED AS A GIFT TO THE PEOPLE OF THIS STATE IN THE NAME OF HANNAH LESLIE BAKER AVANT, A CITIZEN OF FLORIDA FOR NINETY-THREE YEARS

“The person who did live here,” I heard the woman say as I turned back to the group, “was a kind old lady who loved cats and took great care of them.” For effect, the woman pointed to a huge tom who began licking himself just as the children turned to stare.

“Her name was Mrs. Hannah Avant,” she continued hastily. “She was a charter member of Coronado Methodist Church, a prominent real estate agent and an admirable, loving woman respected by all who knew her. Her generosity has given us a piece of Florida as it used to be.”

She went on solemnly for a while about how Florida used to be and she might have even mentioned something about hats and dying of heatstroke in a watermelon patch.

I didn’t catch it all because I was wondering if Mrs. Hannah Avant’s ashes, her mean, parsimonious old ashes, were blowing then over the water and pier, coming to glaze the children’s toes and Fingers and perhaps penetrate a part of them as deeply and easily as the air breathed in beneath those ancient winking live oaks.

Tags

Cheryl Hiers

Cheryl Hiers is a writer who lives in Ormond Beach, Florida. (1983)

Born in North Carolina and raised in Florida, Cheryl Hiers is currently doing graduate work in English at Vanderbilt University. “A Citizen of Florida” is the title story of the collection which forms her master’s thesis. (1981)