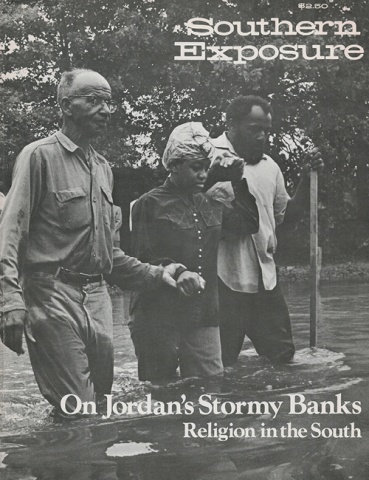

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

From the days when John Wesley first set foot on American soil at St. Simons Island, Georgia, right up to the present, the state of Georgia has continued to play an important role in the Methodist church's history. You might say the state provides an excellent example of Methodist growth and success. Georgia Methodists were the first denomination to erect their own church in Atlanta in 1848, when that city was just beginning its role as the hub of Southern transportation. By the turn of the century, Atlanta could boast more Methodist congregations and members per capita than any other city in the New World. It underwent a burst of growth when land taken from the Creek and Cherokee tribes was opened to Virginia and South Carolina settlers.

Recognizing the need to train their young, Georgians decided to establish their own Methodist school, Emory College, in 1824 at Oxford, thus following a tradition of education in the state which extended back a century to when George Whitfield, Wesley's famous colleague, founded a school and orphanage. Most of the Atlanta church money went to develop all-white Emory College or to build even larger, more elaborate churches. That's where much of Methodist Sunday school official and Coca-Cola founder Asa G. Candler's money went. Through the years Coca-Cola wealth has financed more church and school construction (particularly Methodist) in Georgia than any other source of donor capital.

Emory College and Georgia also figure heavily in the history of Methodist controversy. It was the slave ownership of a black woman by Emory's board president, Bishop James O. Andrews, that touched off the split between the Northern and Southern Methodists in 1844, the first of several splits in Protestantism over slavery. The Bishop couldn't break the law which forbade freeing his slaves, the Southern church rationalized, so he shouldn't be faulted or asked to give up his office. Ninety-four years later, Bishop Warren A. Candler (Asa Candler's brother), a former president of Emory, presided at the meeting where the Southern church decided to rejoin the North. Bishop Candler had led the forces opposing union on the grounds that the Northern church was too rationalistic and liberal and would give too much power to black bishops.

It was also at Emory College that Professor Andrew Sledd, Bishop Candler's son-in-law, was fired in 1902 for publicizing his anti-lynching sentiments. Candler defended the young man, saying he really wasn't for Negro equality; he was just opposed to mob violence. With the sides of the controversy so astutely defined, lynching soon became one of the biggest social issues for the church in the 1920s and '30s. Many white Methodist women in the South recognized their social position in the ideology of racism “for the protection of our women” and led the fight to end lynching, often against their Methodist brothers.

The Candler Brothers

The Candlers were the sons of a prominent Georgia plantation master, slaveholder and Indian fighter (an enforcer of the "Cherokee Removal — Trail of Tears" from Georgia to Oklahoma) and a fundamentalist mother. They combined the attributes of stern religious fervor, practical ingenuity and aristocratic self-righteousness to find success after the set-back of the Civil War. Warren Candler graduated from Emory College to become an editor of the Methodist Christian Advocate, then president of Emory in 1888. Brother Asa became a druggist in Atlanta and built up his capital to purchase the newly invented Coca-Cola. He transformed it from a local headache/hangover remedy and "lift-giver" (it contains caffeine, sugar and phosphoric acid) to the most advertised product in America in 1909 and a $25,000,000 company in 1919. With other relatives assisting, Warren helped his brother gain markets for his drink; he also held stock in the company. In turn, Asa helped Warren finance several major religious enterprises for Methodism.

The year 1898 was critical to this joint venture. Warren became a Methodist bishop and was given charge over starting a mission in Cuba, the first territory outside North America claimed by the US as bounty for its part in the Spanish-American War of 1898. Bishop Candler aimed to fulfill the church's ambition to expand Methodism into Latin America "with bread in one hand and the Bible in the other." Brother Asa was also casting an eye on foreign markets as he told Coca-Cola stockholders (mainly relatives) the same year "that wherever there are people and soda fountains, Coca-Cola will, by its now universally recognized merit, win its way quickly to the front rank of popularity." As in the States, the brothers shared the same program: winning new territory and new converts for the greatest of America's products — Christ and Coca-Cola!

Capturing Cuba for Methodism and Coca-Cola was not, however, a simple matter. The Bishop and his American missionaries complained of the evil effect of centuries of "Romanism." They weren't referring as much to the Cuban people's poverty or lack of freedom due to colonial rule as much as they were to the inability of Cubans to read the Bible, to what Bishop Candler called their "dullness," and to their lack of Church-sanctioned marriages and funerals. Meanwhile, Coca-Cola's agent in Cuba reported his problems to Atlanta headquarters: "As a rule the average Cuban doesn't know and doesn't care what he is drinking, and the words 'hygienic,' 'pure materials,' and 'cleanliness' have no meaning to him; but when once he learns that there is a a difference, that Coca-Cola has more to it than wetness or sweetness, we have secured a steady consumer and an advocate of the drink."

To the Candler brothers, overcoming these "problems" and achieving success would require that the Cubans give up their old ways and become like Americans. As Bishop Candler told the press: "The North American and South American continents cannot be bound together firmly by ties of commerce alone. They will become fast friends when they think and feel alike. Our universities, if they are richly endowed and adequately equipped, will serve this end more effectually than all the consuls and commercial agents who have been or can be engaged to accomplish it. In this matter our commercial interests and our religious duty coincide."

The key, then, was education; but not just any kind would do. As brother Asa intoned, "it must be permeated with the type of Christianity that makes for a wholesome conservatism politically and socially and for a blessed civilization crowned with piety and peace." And so, at the Bishop's insistence, a Methodist college was immediately begun in Havana "to implant a knowledge of the saving power of the gospel and Christian Culture in its students, and through them to make its influence felt throughout the nation." Not surprisingly, the school's "greatest benefactor" was Coca-Cola's Asa G. Candler, donor of tens of thousands before his death in 1929. Appropriately, the school took the name Candler College.

Education of youth to develop local leaders with the right attitudes and to create a favorable cultural climate was the key to commercial/religious success and the function of the college. Bishop Candler frequently axed those independently-minded Cubans he thought "unfit." Coca-Cola relied on Americans for its managers in Cuba for many years and when they did begin to change and use local leadership, they put the candidates through a rigorous screening process. "Every peg is made to fit some hole and and every hole needs a peg to fit it," Asa Candler once told a group of graduating high schoolers. "The cry always in the business world is for first class pegs to fit first class holes. How shall we get first class fits? That's the great question." For Methodism and Coca-Cola in Cuba the answer was Candler College — or an education in America.

Emory University

Actually, Cuba was only one of many joint ventures tackled by Methodism and Coca-Cola. And coincidentally, the biggest, costliest, and the most gratifying to the Candler brothers was another church college: Emory University. In fact, in 1899, the same year Methodism and Coca-Cola entered Cuba, Asa Candler made his first recorded contribution to Emory College (which counted two of his sons as alumni); brother Warren was the board president and urged Asa to become a trustee. Within a year, Asa had become chairman of the board's finance committee; six years later, he was the board president.

Then in 1914, the Methodists lost control of Nashville's Vanderbilt University to an unyielding board of trustees who liked Andrew Carnegie's offer of a million dollars for a medical school more than they did church control. With a flurry of activity, the church appointed a special education commission to start a new university that they would own and control "in perpetuity." Bishop Candler became commission chairman and brother Asa the treasurer. The cards were clearly stacked. After Asa donated $1,000,000 to the commission (at a time, the biggest gift to a Southern college made by a Southerner) and pushed Atlanta's Chamber of Commerce to commit themselves for $500,000 more, the Commission announced that Emory College would move to Atlanta — to a 75-acre suburban plot donated by Candler — and become Emory University. Candler continued as board president until his death, and the Bishop became university chancellor.

For the next fifteen years, Asa Candler pumped money into the new campus. Emory's seminary became the Candler School of Theology in Bishop Warren's honor; nephews and in-laws, rich from Coca-Cola, financed dormitories and other buildings; the law school building featured a bust of its principal donor, brother John S. Candler, Coca-Cola legal counsel and Georgia Supreme Court Justice; Asa gave the library which became known as Candler Library; and in a move that shocked even wealthy Atlantans, Asa transplanted Wesley Memorial Hospital, which he and brother Warren had started in downtown Atlanta, to the remote surburban campus and financed construction of a medical school. By his death in 1929, Candler had pumped some $8,000,000 into Emory University. His son, Charles Howard Candler, who followed him as Coca-Cola chief, also succeeded him as Emory board chairman and chipped in another $7,000,000 before he died in 1957, not counting his wife's gift of the campus' large and prestigious Glenn Memorial Methodist Church, named for her father.

Today, Emory continues its tradition as a training ground for the South's rich — and for a number of children of Coca-Cola bottlers around the world, particularly those from Latin America. With special emphasis on its professional schools, it proudly produces more Methodist ministers than any other seminary, 60% of the doctors and 80% of the dentists in Atlanta, and over half the members of the gilt-edged Atlanta Lawyers Club.

Emory's all-white, male Protestant Board (with six Methodist Bishops) is still laced with Coca-Cola connections, including Asa's grandson, who sits on both boards, the sons of three other Coke directors, and nine directors of Coca- Cola's local bank, the Trust Company of Georgia. Emory's current money man and official "principal counselor" is Robert Winship Woodruff, son of the organizer of the 1919 sale of Coca-Cola from the Candler family to a group of New York and Georgia capitalists.

Woodruff, now 82, has been the main power behind Coca-Cola since 1923. Through his foresight, Coca-Cola expanded with another war. World War II, by following the Gl around the globe at the request of General Eisenhower and others. When the war ended, Coke switched its foreign plants to civilian management with civilian markets and became a multi-national corporation overnight. Woodruff returned the favor to Eisenhower by helping his war-time friend and golf partner get nominated and elected President. Another close Woodruff friend is Billy Graham, a mass media version of the evangelists Billy Sunday and Sam Jones, who had counted Asa G. Candler among their benefactors.

Through the years. Woodruff's gifts to Emory have grown in excess of $50,000,000, primarily to finance the Woodruff Medical Center. His foundation gave the money to build the school's super-modern Woodruff Library. Over half of Emory's $177,000,000 endowment portfolio is tied up in Coca-Cola stock, making it one of the largest single stockholders; however, even its holdings (roughly 1 million shares) are overshadowed by Woodruff's numerous foundations and pyramiding holding companies: Coke controlling ownership is still largely a one man/family affair.

It is no accident that Coca-Cola and Methodism found a common interest in religious education. Men like Asa and Warren Candler understood (and Robert Woodruff understands today) the critical importance of disciplining minds and tastes to the values of American Protestantism and capitalism. "Religious education," Asa often pointed out, "supplies restraints" which regulate ambition, discipline greed and sanctify the status quo. In turn, the Bishop testified, their brand of Christianity made capitalism a "holy" science, for capitalism plowed its excess "fruits" into Christian enterprises to train the next generation and perpetuate the cycle.

This article was excerpted from a longer pamphlet written in 1972.

Tags

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.