Captive Voices; Prisoners of Learning

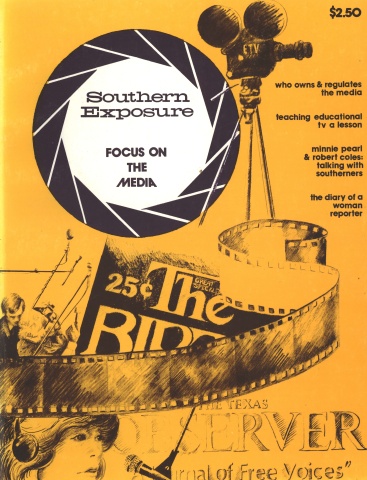

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

Investigative journalism and the role of a free press were widely discussed topics in 1974. While Watergate and impeachment news headlined the country's news media, an important struggle for a free and substantive press was taking place in many high schools across the country.

Stories of student journalists, their advisors, school authorities and the student press are contained in Captive Voices (available from Schocken Books, New York for $1.45), the report of the Commission of Inquiry into High School Journalism. The Commission was convened by the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial, a Washington, D.C., organization concerned with the problems of disadvantaged young people. Comprised of twenty-three members including such journalists as Jules Witcover of the Washington Post and John Seigenthaler of The Tennessean, the Commission conducted an eighteen month investigation highlighted by public hearings, two of which took place in Charlotte, North Carolina and San Antonio, Texas.

Captive Voices contains sections on censorship, minority participation, the quality of journalism education, the role of the established media, a legal guide for student journalists and recommendations for needed change. One recommendation calfed for local conferences to discuss with students and teachers the findings of Captive Voices, the importance of more in-depth reporting and to stimulate an awareness of First Amendment free press rights.

To study the potential for such a conference in North Carolina, Lloyd DeFrance, a nineteen-year-old graduate of Guilford High School in Greensboro, has been working in several North Carolina counties as a Robert F. Kennedy Fellow. He describes his work and the impressions which North Carolina students have of their newspapers.

"Most high school journalists emphasize the layout of their newspapers rather than the content. The way it looks is more important than what it says. This is understandable. If their paper looks nice, the students receive praise from the administration and their adviser, even if the content is superficial. If on the other hand, the newspaper says something important, the students get hassled continually.

"Students know this, and the result is that the most common form of censorship in North Carolina originates from the students themselves. Knowing what can or can not be printed leads to a conscious avoidance of many topics.

"Censorship also comes from teachers and administrators, especially when an article touches on a controversial issue such as student rights, minority affairs or criticism of school officials. The threat of a cutback in school funding or a lowered grade may 'censor' an article. At other times an administrator will simply ban the publication of a story.

"In order for censorship to end in the schools, newspaper staffs must realize that they have the right and duty to publish substantive and informative stories. The courts have held that students may publish and distribute any literature, subject to the limitation that it not be (1) libelous, (2) obscene, or (3) disruptive of the educational process.

"How can the content of a student newspaper be improved? Close the communication gap between the newspaper staffs and the student body. Staffs should ask students what types of articles they are interested in. Experience has shown one that careers, jobs, politics and social problems are often the answers one receives. The key is not so much what issue one writes about, but rather the depth of analysis and investigation which is done.

"Content might also be improved by an examination of the types of people on the staff itself. If the staff is comprised entirely of white, college-bound students, then the content will probably reflect that makeup. The problem lies partly with the methods of choosing newspaper staffs and partly with the conditions under which minority groups and poor people live and attend school. Sometimes a student must have a certain grade average (B or better) in order to 'qualify' to be on the staff. This method of choosing staffs makes for a one-sided paper. One year's staff selecting next year's staff often leads to 'clique' control.

"Many minority students and poor whites have grown to accept as fact their history of non-participation on newspaper staffs. They consider themselves apart from their school newspapers because they never read anything about their culture or lifestyle. Poor whites and the minority students need to be encouraged to become involved. A well-rounded staff usually insures a well-rounded paper.

"What can an individual student do to make his/her school newspaper better? The first thing is to get involved. This will allow the individual to discover a paper's problems. If the problem is a lack of investigative reporting, then the individual should select a topic, investigate it thoroughly and then push for the story's publication.

"If the problem is a legal one, contact an attorney, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), or one of the community organizations concerned with student rights. The answer may be a court suit or an independent paper. Sometimes a call from a lawyer or the editor of a local newspaper will help to set things straight. The worst thing a student can do, though, is nothing.

"The final reason why high school is in poor condition in North Carolina is the prison-like atmosphere in which students are forced to 'learn.' Teachers must become friends and schools places where students are happy to learn and grow. Until these things are accomplished, students will continue to be turned off and continue to write about the senior mascot and maypole dancing."

Tags

Leonard Conway

Leonard Conway is the Staff Director of the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial in Washington, D.C., and served as staff for the Commission of Inquiry into High School Journalism. (1975)