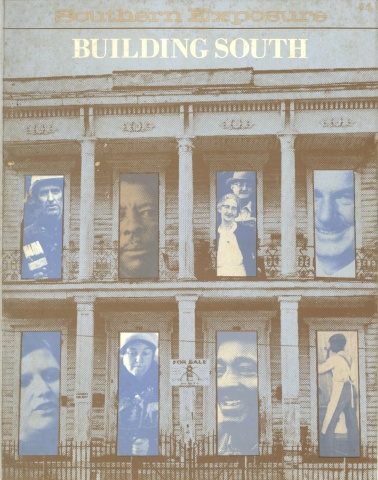

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 1, "Building South." Find more from that issue here.

Whether the object is corporate headquarters, county courthouses or palaces for the Medici, architecture reflects its period's political economy. Over the past two decades, architect John Portman's work has epitomized the political economy of Atlanta and the Southeast. His hotels, offices and commercial buildings serve as the most visible symbols of this Newest South's urban affluence and ambition. And in the process of altering Atlanta, Portman has also fundamentally changed the relationship of the architect to financial and political power.

During World War II, the South’s effective industrial capacity increased 40 percent as its traditional industries, textiles and wood products, expanded and new industries like petro-chemicals arrived. In the next two decades, the region’s population mushroomed and per capita income rose by 1960 to 72 percent of the national average, up from 50 percent in 1930.

At the center of Southeastern expansion stood Atlanta. Long the transportation hub of the region, Atlanta was becoming the major marketplace for transacting the region’s business. In 1960, John Portman found himself in the whirl of Atlanta’s expanding opportunities. A native of Walhalla, South Carolina, Portman had received an architecture degree from Georgia Tech in 1950 and established a partnership in downtown Atlanta. His design for a small medical building was published in Progressive Architect in the mid- ’50s but the building was never built, “an architectural success and a promotional failure,” as Portman saw it. He vowed to develop, as well as design, future projects to ensure they would be built.

Portman’s office was in the Loew’s Grand building three blocks from Five Points — the convergence of nineteenth century rail lines around which downtown Atlanta was built — and across the street from the Belle Isle Garage. The garage, which had held a small regional wholesale furniture mart in the late ’40s, was subsequently taken over by the Veterans Administration. Portman’s father, who worked for the GSA, tipped his son that the building would soon be returned to its owner by the VA. Searching for architectural contracts, Portman queried the owner about his plans for the building. A garage, unless you can think of something better, he was told. Portman says, “I came up with the idea that it would make a great exhibition space because you would have to do very little.”

With the garage, John Portman created a place for institutional buyers from all over the region to do business with furniture manufacturers. The project was an extraordinary commercial success. The old building filled within a year and demand for more space was soon strong enough to support a new merchandise mart.

Portman was not the only person to recognize this demand and, as the new kid on the block, was not in an exclusive position to execute the mart project. Another member of the emerging business elite, Bob Holder, also wanted to develop the project. Holder was largely a one-man show, doing business out of his car on one of the first automobile telephones Atlantans had seen. More importantly, he had owned the land on which General Motors built its suburban assembly plant and had successfully developed the Peachtree Industrial Boulevard on the northeast edge of Atlanta, creating the area’s largest industrial complex.

The outcome of the Portman- Holder competition would have a significant impact on the development of Atlanta. Portman proposed a site near the Capitol City Club, on the fringe of what was then the downtown core. Holder proposed a site some 20 miles from downtown beyond his industrial development. “It became quite a struggle between his and our group,” recalls Portman. “They were the proven developers, they had a board of directors on which substantial local people were involved, and they made a big effort to create the impression that we were just young guys out in left field.”

When Holder’s group ran into trouble with private financing, they nearly convinced the state to build the mart under a public authority. But Portman’s new friends, some of whom were relative newcomers or marginal members of Atlanta’s elite, came to his rescue. Mills B. Lane, the flamboyant transplant from Savannah and president of his family’s Citizens & Southern Bank, began flexing the muscles that came from running Atlanta’s and the state’s largest financial institution. As Portman judiciously says, Lane “convinced the key people in the state government that there was no point in spending public money on a project that could be done perfectly well by conventional means.”

Ben Massell, a prominent downtown realtor, who was outside the old elite’s circle because he was Jewish, agreed to buy the land for Portman’s mart and provide the additional equity needed to secure a development loan. When Metropolitan Life agreed to put up eight of the 15 million dollars that the project would cost, Portman, Massell and Lane had won, and Portman’s career as entrepreneur and as developer-architect was launched.

In addition to being the largest building in Atlanta in 1961, and the linchpin for regionalized furniture wholesaling, the Merchandise Mart accomplished three other things: it gave Portman the leverage and attention he needed to join an increasingly powerful assortment of upstarts who gradually merged with, and later subsumed, the old boy network that, in the early 60s, still ran Atlanta like a family company; it focused development pressure on central Atlanta in an era when more mature cities were developing on their peripheries; and it gave Portman sufficient economic security to experiment with designs that suited his evolving vision of elegant and commercially practical urban environments.

By his own account, Portman “began seriously thinking” about the “guiding principle of architecture and design” on a 1960 trip to Brazil for the dedication ceremonies of its new capital city, Brasilia. He was excited by the prospect of seeing a city completely designed by architects, but was quickly disappointed to find “nothing but great blocks of buildings arranged in military order. Some of the architecture is actually quite interesting,” he later wrote, “but the buildings seen together become objects arranged in a sterile, two-dimensional pattern that shows no understanding of human scale or of the need for people to become involved in their surroundings.”

The trip to Brasilia left Portman convinced that many of the tenets of the architectural profession “did not work very well at the scale of an entire city. Older cities, no matter how badly their designs had evolved, were still better at providing for human needs” than the new towns. The task, he concluded, is “to restructure our existing cities, not build new ones.”

Portman returned to Atlanta with the ambition to become a megadeveloper and pledged to make “buildings more responsive to human values.” His approach to “design at the scale of the city” flowed directly from his status as the architect and owner of Atlanta’s biggest building. As Portman wrote in a revealing moment,

“We had just finished the largest building in Atlanta, the Merchandise Mart, at one of the major intersections and I felt that we could not allow just anything to happen up and down the block and across the street. Why not take the first steps toward creating a larger-scale environment? So we started assembling land. We gained control of the plots next door to the mart and parcels in other key locations, with the specific aim of creating new environment that followed a master development plan, would grow step by step, and would add to, not obliterate, the life, vitality and interest of the existing city.” (Italics added.)

With impressive tenacity, John Portman followed his plan. By 1970 he had conceived his master blueprint for Atlanta’s downtown, and put the cornerstones in place. In the next decade, he kept adding new blocks, adjusting and expanding the plan; fighting off government agencies, competing realtors-developers and hos¬ tile neighborhood groups; co-opting here, stonewalling there — and all the while exporting the Portman style of grand-scale design to other cities and countries.

The apex of Portman's achievement as designer-developer is the $230 million Peachtree Center Complex, the better parts of which were built in the early 1960s. Extending from the Merchandise Mart to and across Peachtree Street, it includes 1,900 hotel rooms, more than 10 restaurants, parking, two office buildings, and over 30 shops. If it isn’t in the shops, it can be sent in. Many a conventioneer or department store customer never leaves the property. For them Peachtree Center is Atlanta.

The early ’60s were satisfying times for upper-class Atlantans. An ebullient confidence accompanied economic expansion. Major league status was on the horizon. Portman’s Peachtree Center Project reflects this confidence. It is invitingly open to the public. Please come in. Sit down. See and be seen. Have some lunch. Cut a deal. Enjoy an urbane, open, accessible public space.

“What I wanted to do as an architect,” said Portman, “was to create buildings and environments that really are for people, not a particular class of people, but all people.” The first parts of the Peachtree Center project do precisely that. A 40-foot-wide entrance in front of the east tower leads to an open-air cafe and assorted shops. The border between public space and private space is a feature in itself, including coffee shops and browsing points at shop windows and newspaper stands. During the seven or eight months of the year that Atlanta enjoys a moderate climate, this public space, filled with people, is one of the most vitally active parts of the city.

Portman’s finest project is his first atrium hotel, the Regency-Hyatt. When it opened in 1964, the $20 million, 23-story Regency changed the character of Atlanta’s economy. The Chamber of Commerce’s national PR campaigns featured the Regency as the symbol of Atlanta. Conventions which were headed for San Francisco, New York and Chicago shifted to Atlanta. The Regency was talked about in board rooms across America.

It is an extraordinary building. Atrium hotels date back to Spanish inns where the rooms were grouped around a court. Denver’s Brown Palace and Atlanta’s own Kimball Hotel preceded the Regency in this country. What is new is the scale and the flamboyance.

The atrium in the Regency is 22 stories high. Visitors enter from a drive in front of the building through a short, narrowing tunnel before arriving into a 120-foot square, 220-foothigh space. The transition from outside was known colloquially for years as the “Jesus Christ” entrance, because the impact on first-time visitors usually elicited that phrase.

The space is chaotic and overwhelming. Huge sculptures loom, small restaurants edge onto the floor, and elevators ringed in the lights of Tivoli Gardens glide up and down a concrete core. It is the ultimate urban vision a la John Portman. The sterile, structural order of his Bauhaus predecessors is a faint echo. Like the city, the Regency is chaos, activity and motion. The city is fun, and the Regency is fun. Capped by a revolving restaurant borrowed from the Seattle World’s Fair, the Regency is one of the biggest toys in America. The Beatles were singing “Please, Please Me” and Portman was.

Social reality began to nibble away at the edges of the self-confident vision of Atlanta from the late-'60s on. Rodney Cook, the old-line candidate for mayor in 1969, lost to Sam Massell, nephew of Portman's partner, Ben. As Atlanta's older commercial interests lost some of their political clout, Portman gained. So did black Atlantans, who by 1969 constituted half the city's population and had demonstrated in the streets and in many private meetings their displeasure with the old guard's paternalism. Sam Massell won with black vice-mayor, Maynard Jackson, at his side.

Life began to seem increasingly confusing, even threatening, to the aging elite who had run the city for a half century. The power structure they had known was a social, economic and political union. As Ivan Allen, the last of the old-line mayors, observed:

Almost all of us had been born and raised within a mile or two of each other in Atlanta. We had gone to the same schools, to the same churches, to the same summer camps. We had dated the same girls. We had played within our group, partied within our group, and worked within our group.

The rising entrepreneurial elite, with John Portman and his Regency Hotel as its most obvious symbols, was not socially of this group. But these young wizards helped the oldtimers ensure the continuing prosperity and peace they desperately wanted for their city. Allen spelled it out:

A favorable image means new industry. New industry means more jobs. More jobs means more personal income and spending. More income and spending means a broader tax base for the city, which means more and better city services, which mean happier people, which is what it is all about.

By the end of the 1960s, the new generation of leadership faced a number of tough decisions about how to keep Atlanta expanding, vital, exciting. Understandably, John Calvin Portman emerged as the architect for its plan of progress, and his Peachtree Center became the image of “America’s Next Great City.”

Portman was not alone, of course. Others had their strategies for Atlanta’s future, including Jim Cushman, who projected a “city within a city” for the Tenth Street area called Colony Square, and most especially Tom Cousins, whose proposed Omni International complex to the southwest of Five Points rivaled Portman’s northwardly directed focus in both physical and financial scale. But Portman had more projects in the ground; his John Portman & Associates and Portman Properties, Inc., held over $40 million in assets, counting the Mart and the first parts of the Peachtree Center, and handled over $75 million worth of new business in 1970 with a staff of about 50 architects, accountants, engineers and city planners. Portman also had the mayor’s ear.

In 1970, Portman assumed the presidency of Central Atlanta Progress, a midtown Chamber of Commerce that lobbied for unified business action and increased government support for downtown development. Among the new president’s first moves was convincing Mayor Massell and the city council to join CAP in designing a 25-year master plan for the core business area’s development. The six-member policy committee overseeing “The Central Area Study” included Massell as chairman, Portman as cochair, three city council members and Mills B. Lane of C&S Bank. (The Lane-Portman partnership continued; a few years later, Portman joined the board of the bank where he still serves).

The CAP study, according to the city planning director, offered a blueprint “to shape Atlanta’s central city into one which will meet new standards of mobility, economic choice and human habitability.” It featured a four-level Peachtree Street in the blocks stretching from the Merchandise Mart to the Regency Hotel, with levels for traffic running in each direction over a subway tunnel and beneath a pedestrian “promenade.” The plan also incorporated a mass transit system (which voters had rejected in a 1968 referendum), and it legitimized a network of new highways that had become an increasingly thorny issue for the new breed of commercial leaders.

The Central Atlanta Study, released in late 1971, received uniform applause from state and local promoters of highways and transit systems. Transformed into an elaborate model of balsa wood blocks and roadways, it remains to this day, almost as a shrine, in the lobby of the Central Atlanta Progress’ offices. It unveiled Portman’s grand scheme for downtown, which still serves as a backdrop for his design-development plans. But it raised the eyebrows of a number of neighborhood leaders who had already begun fighting the state’s proposed highway additions. In short order, the Study receded behind the intense and highly visible battle being waged among politicians and private businessmen.

The Central Atlanta Study endorsed two types of transportation plans which undermined each other. In advocating highways, it echoed the self-fulfilling prophecy that had suburbanized most American cities: build the highways and people will move farther out to the suburbs because the highways make them accessible. But in selling their transit plans, Portman’s crowd argued that suburban expansion could be reversed by a re-migration to the central city which would justify — and be speeded by — an in-town mass transit system.

Atlanta’s in-town white neighborhood groups united and filed a suit to block the state’s proposed expressways to the northern and eastern suburbs. The public planning agencies, which had endorsed the Central Atlanta Study proposal for both more highways and a mass transit system, backed off from their support of highways, saying the city could not build two systems. Federal funding sources also balked, and city hall’s planners began drafting zoning regulations to compel enough new development around the transit system’s stations to guarantee the flow of transit-riding customers required to support the system. But downtown business interests and Portman stuck behind the Central Atlanta study plan: both highways and transit.

In 1973, vice-mayor Jackson was elected mayor with crucial support from white, in-town neighborhood voters attracted by his opposition to highway construction. Though the Georgia DOT still wanted to build the roads and had acquired and cleared much of the land for them, Jackson’s victory helped temporarily shelve the expressway plans. MARTA, the transit system, was under construction, and Portman and his downtown allies concentrated on having the city’s transit system built their way. Though the Central Atlanta Study had sold the city MARTA by claiming that it would create its own demand, the study’s authors denied the city’s right to specify the location of developments which would pay the transit piper. They argued that the city’s proposed zoning ordinance would stifle development. And they created a rhetorical smoke-screen by further arguing that many existing developments could not have been built under the ordinance. In brief, downtown business advocated no restrictions on the private sector’s right to build whatever it wanted whenever it wanted. The zoning ordinance was emasculated.

Though Portman's crowd can exert imposing muscle in battles like the one over transit station development, politics in Atlanta has become little more diverse and less subject to the desires of a traditional power elite. The days when a few white men decided who could do what, where and for how long are slowly passing. The zoning ordinance fight would never have happened in the ‘60s when Ivan Allen's club held both economic and political control. Having lost some of its political power, downtown business must now fight for its economic interests. It usually wins, but at least there is some opposition.

The building is a 1,200-room convention hotel, 754 feet and 73 stories tall, by far the tallest structure in the city. It is also the tallest building in the South and the world’s tallest hotel. Metropolitan Life and C&S Real Estate Investors put up the bulk of the $56 million it cost, and Charlotte’s J.A. Jones — builders of the Regency, the Oak Ridge Y-12 nuclear weapons plant, the National Gallery’s new East Wing and Vietnam’s tiger cages — erected it.

Peachtree Plaza echoes the cylindrical form which Portman first used in his addition to the Regency. There the cylinder allowed for a maximum number of additional rooms on a limited piece of land without walling in the original building’s southside balconies. The Plaza’s form is economical also, but its massive, foreboding five-story concrete base renders the whole building inaccessible from the sidewalk. At the level of Peachtree Street, it crowds the sidewalk and pushes the pedestrian away. The building’s entrance features planters, the origin of which are the subject of two revealing local stories.

The first account harks back to the kind of thinking that shaped parks given to the city by Coca-Cola’s Robert W. Woodruff. Nowhere in those parks is there a bench: Woodruff, Atlanta’s best-known “anonymous donor,” believes that benches attract winos and riff-raff whose presence offends (necessarily) upstanding citizens. This line of logic may have led to replacing the benches along Peachtree Street with planters and spikes.

The second story says that benches were actually installed, but too close to the sidewalk, so that passing pedestrians crowded those who had stopped for a rest on the bench. In response to being crowded, people sat on the backs of the benches — a risky business because if they leaned back too far, they would fall off the bench into the moat below. The benches were replaced with planters, and spikes were added to make certain that no one sat down and fell into the moat.

Whichever story you believe, the end result is the same. There are no benches and the street level entrance is threatening and inaccessible. The Plaza’s impact on Atlanta goes further than its street level ambience, however. Because Atlanta was built on the rolling hills of the upper Piedmont and because Atlanta streets follow the ridges of these hills wherever they wind, Atlanta is an extremely confusing city to travel through. Peachtree Plaza, 26 stories taller than any other structure in the city, provides a handy point of reference for downtown from almost any place in the city.

But for the full meaning of Portman’s work, one must look down as well as up. Because deep underground, MARTA subway construction demonstrates how Portman’s buildings and power profoundly rely upon, and shape, public spending. Like the Plaza, this underground scene also shows urban architecture in defensive retreat from an earlier openness, a burrowingin far deeper and narrower than Portman’s four-level fantasies of the early ’70s.

Subways are usually built by digging up streets, pouring concrete stations and tunnels and rebuilding the streets. Except when John Portman is in the neighborhood. In a display of financial and political clout, Portman forced MARTA’s subway construction underground in front of Peachtree Center. Small businesses have died all along the path of Atlanta’s subway, since excavation has cut off access to them. But traffic moves easily in and out of Peachtree Center because construction there is 125 feet below Peachtree Street. Again there was opposition, but again Portman won.

Tunnels cost about twice as much as digging up streets. To pay for the increased construction cost, the size of the Cain Street (Peachtree Center) Station was reduced. Portman’s early plans for Peachtree Center showed a street-level mall and the subway beneath it; access points to the street from a block-long station were plentiful. But the station under construction — one of the deepest in the world — has only a single access point which requires transit-riders to take four escalator trips into the well. Compressing a spacious station into a mine shaft echoes the Plaza’s paranoid approach to security.

Atlanta managed to back the federal government into paying for much of the new subway, but not all of it. Atlanta’s share will either come out of the fare box or out of taxes. Since the Central Atlanta Study’s expressways have been revived at Portman and the Georgia DOT’s urging (see sidebar) — and since the downtown developments will not necessarily focus around transit systems — prospects for fare box receipts seem dim. The notion that Atlanta owes John Portman a lot takes on new meaning.

Today Portman's office is busy with projects from Singapore to Times Square to his home turf. He is embroiled in a downtown battle with fellow developer Tom Cousins over the future location of Rich’s department store, each trying to push development in the direction that would most benefit his holdings. Portman’s pre-breakthrough project, the Belle Isle Garage, is being torn down for Georgia-Pacific’s new world headquarters, which will be taller than Peachtree Plaza. And the Merchandise Mart has spawned a Portman addition, the Apparel Mart. As the garment industry’s sweatshops continue to move South, they provide another entrepreneurial opportunity to create new wholesale marketplaces connecting the region’s increased garment demand with its newly arrived suppliers.

John Portman has produced some superb architecture. The Regency has set a standard for atrium hotels that remains unsurpassed, and Peachtree Center’s extension of public space is an asset to the city. But those buildings date from an era when Atlanta’s business elite had unchallenged control of both the local economy and local government. As the city grew slightly more democratized, as more interests played effective politics, the elite and the buildings have become defensive. The grand spaces within the Plaza and the Apparel Mart are across the bridge and over the moat — open only by explicit invitation. Portman’s latest work turns its back to the city, crowds the site with blank walls and leaves the people on the street excluded and vulnerable.

For all his talk about building for “all people” and honoring universal “human values,” while renewing our center cities, Portman’s vision and deeds are consistently narrow in their beneficiaries. The brand of top-down planning which Portman practices will never recognize the Southeast’s cultural values and resources. Culture is not an importable commodity, but that is precisely what Portman’s elevation of Atlanta to the nation’s third-ranking convention center has required. The dependence on tourism, furniture and garment buyers, relocating corporations and foreign investors for design and planning inspiration is a formula for cultural blindness as well as economic instability. Portman’s Atlanta neither sees nor appreciates the indigenous values of its own society.

Finally, this man who professes a belief in rugged economic individualism is deeply indebted to and enmeshed in political machinery which uses public money and influences public decisions to mold cities for the good of the few. Jonathan Barrett, one of Portman’s many idolators, observed that, “He has solved the problem that has beset architects since the end of the eighteenth century: how to replace the aristocratic patron who had traditionally made it possible for the architect to do his work.”

Portman did this, but only by becoming the aristocrat himself.

“Man is a creature of nature. He instinctively likes trees, nature, landscaping, a running brook, a log fire. This idea must be woven into the physical environment if we are to create a hotel that is an exciting place.”

– John Portman

“Why have I been able to do all that I have without one penny of city, state or federal funds? Because I'm an architect and have been able to maintain control and been able to not just build something but think in terms larger than that. It's had an impact.”

– John Portman

Culture vs. Neighborhood: Portman raises the stakes

While the state's plans for East Side expressways were shelved, Atlanta's East Side neighborhoods organized behind the concept of a “Great Park” to fill the previously cleared right-of-way which the Georgia Department of Transportation (DOT) still owned. The neighborhoods hired local architect Randy Roark as a consultant and drew up a formal plan through their newly formed Atlanta Great Park Planning, Inc., which received Mayor Maynard Jackson’s praise. The neighborhoods’ “Great Park II Report,” like a previous citizens’ study, recommended that the right-of-way be used for housing and recreation, not transportation. Georgia DOT countered with a proposed four-lane connector to suburban DeKalb County with “a number of recreational and landscape features.” In 1979, Governor George Busbee appointed John Portman to pull together an alternate plan to the neighborhoods’. Portman, “donating his time,” teamed a group of planning and design firms as Land Use Contractors, Inc., which the state funded to the tune of $225,000. The neighborhood groups and the mayor watched angrily and apprehensively as Land Use Consultants, Inc., swung into action.

The Process

One of the canons of contemporary planning is citizen participation. After the blunders of grand urban renewal schemes conceived in board rooms and highway plans announced at final public “hearings,” some planners have finally learned that citizens do not want to be treated as acquiescent cretins. They want to be involved in generating a plan from its beginning, to have their ideas and interests reflected in the plan’s outcome.

The neighborhoods’ Great Park plan evolved from the citizens, the planners and the mayor discussing what the plan was intended to do, and evaluating the ideas and interests of the neighborhoods, the city and the commuters from suburban DeKalb.

Portman’s plan evolved from on high. It was unveiled like one of his private development projects, delivered in a glossy, six-color book (with Great Park centerfold). Before the proclamation, Portman’s perfunctory bow to “citizen participation” consisted of some interviews, then silence, then secrecy. No discussion.

The Product

The two plans differ in product as much as they do in process. Portman provides both the radial roads that Georgia DOT wanted — in fact, with a heftier price tag since one is a tunnel and the other is a parkway rather than an expressway. The Portman plan opens with a boulevard as wide as anything Haussmann ever sliced through Paris. The boulevard ends in a flashy fountain in front of the small Victorian cottage which was Martin Luther King’s birthplace. The two-block-long boulevard, Portman’s way of apologizing for indigenous culture, will engulf the King birthplace like a gargantuan parking lot.

Jimmy Carter’s presidential library, the Cyclorama (lifted from its present southside location), an amphitheater, a museum of natural history, a Venetian-inspired cultural center, a club for foreigners and some high-density housing complete the physical plan. There will be no parking save for a small lot adjacent to the Inman Park transit station.

Why this plan? Portman, in a rare public appearance in November, 1979, explained that, “Atlanta is subject to two development forces. One is the competition for snowbelt to sunbelt-bound industries, and the major competitors are Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston and San Diego. The second force is international development,” i.e., developing ties with foreign money and industry, especially Europe and Japan’s.

In the competition for snowbelt industries, Portman believes Atlanta loses to the three other sunbelt promoters because ‘They have a stronger cultural base.” The captains of industry who make corporate relocation decisions want “culture,” and the competition for foreign money pivots on the same selling point. According to Portman, Atlanta needs an international club “because foreigners can’t get into our private clubs.”

The Costs

Though the clients for this plan are board chairmen and foreign investors, not the citizens of Atlanta, someone must pay for it. Land Use Consultants, Inc., identifies four funding sources for the $157 million pricetag: the federal government, state government, local governments and income from the park.

Transferring the cost of major capital improvements to state and national governments is standard practice for fiscally conservative local governments. Whether $140 million of the projected budget can be exported is an open question. Some capital costs ($17.4 million) and all operating expenses are to come from park revenues. Parks do not usually have revenues. This one is supposed to.

Admission and special events fees are to account for 47 percent of park income. Whether Atlanta’s citizens will pay to get into a city park like this is problematic, but the total absence of parking should make the question moot. The remaining assigned capital and operating costs of the park will be raised by charging each housing unit in the park $1,000 per year for being in the park, although a market for the type of housing proposed does not exist in Atlanta.

The political framework for Portman’s plan is consistent with its physical aspects in its arrogance towards Atlanta’s citizens. Portman envisions a state, not a city, authority. The “advantages” of authorities are that their leaders are appointed, not elected, and that they function with much greater political autonomy than any other form of government. This authority would have its own police force.

There is one area where Portman’s and the neighborhoods’ plans are identical. A couple of decades ago, the residents of the Great Park area were either lower-middle class or poor. With the exception of one black neighborhood, only a few poor people and no lower-middle-income families are left. The neighborhoods have either been gentrified or leveled for road-building. Neither Portman’s nor the neighborhoods’ plans recognize any public responsibility to replace the housing which was destroyed. Some housing will be built, whichever plan is adopted, but none for poor people. It is not even being talked about.

Ultimately the only people who will pay money to get into a park and who have no cars are tourists. Tourists who will stay in the Regency and the Plaza and catch a shuttle bus at the front door, pay their fees and ride on over to pick up a little imported “culture.” When you ask an innkeeper to design a city park you should not be surprised when he designs it for his guests.

Some developments have to be economically exclusive. The people who they attract are the kind who you have to have in city if it really is to be healthy. That came up here in Atlanta out on the fringe of downtown. There is an old housing project that has outlived its usefulness and there had been discussions about rebuilding.

There was a proposal for low-cost housing. But what we want to do is build the kind of housing that will appeal to the sort of people who might otherwise go to the suburbs, outside the city. We explained this to the groups in favor of low-cost housing, including blacks – and they understand.

– John Portman

Originally, Portman's entrepreneurial activity made his architectural fraternity brothers nervous. Many successful architects have been handmaidens to wealth and privilege and many have endorsed a view of culture which emphasized classical European art forms. In their view, developers were people who not only dirtied their hands with crass financial affairs, but also tarnished the profession’s aesthetic image with the grimy task of building.

The second line of resistance to Portman and the whole notion of architects as developers was legal. The state licenses architects to ensure that their buildings do not endanger the public, and Portman’s dual roles provoked a serious professional debate. He recalls:

I gave a speech to the AIA [American Institute of Architects] in 1965 and before they let me on the stage they quizzed me about this relationship. Ethics dictated that if I represent you, I’m your agent and I cannot have any conflicting interests. When they realized I was my own client - how could I cheat myself? - they ruled out that objection. I don’t wish to get into construction and own no stocks in or have anything to do with any building material people. So I never violated their ethics but they were sure I did in the beginning.

Eventually, Portman’s profits played a large part in convincing his colleagues to sanction what he was doing. While their debate was couched in ambiguous and high-sounding references to the public interest, it basically concerned control over the development process. Such control, the architects realized, not only preserves the purity of a project’s design and marketing concept, but also channels the developer’s profits into the designer’s pocketbook. John Portman is now a Fellow of the AIA, its highest award.

Portman is also the role model in architecture schools across the country which have added real estate developers to their faculty. Without even a basic course in economics, students learn about tax shelters, depreciation schedules, syndication — the whole intricate network of public subsidies to private development. The entrepreneur has wrested control of American architectural education from the quiet socialist visions of the war emigres who dominated the schools for decades. Born of the Me Decade, architecture’s new renaissance man conceives of new investment opportunities, manages their construction and lives genteelly on their proceeds. Just like John Portman.

"I hope that my buildings say love people.”

– John Portman

Tags

Larry Keating

Larry Keating teaches planning theory and housing at the Georgia Institute of Technology. (1980)