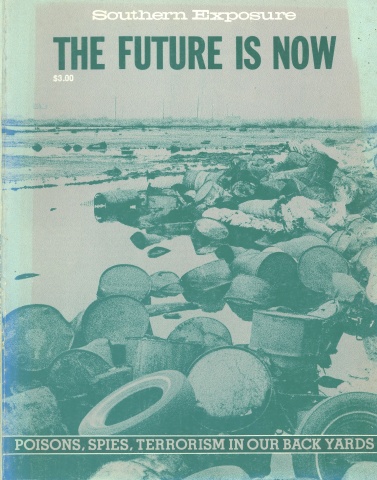

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 3, "The Future is Now: Poisons, Spies, Terrorism in Our Back Yard." Find more from that issue here.

Heard County, Georgia, seems an unlikely spot for gun-toting confrontations between the forces of state authority and the general population. It's a rural county of about 8,000 people lying midway along the state's border with Alabama, far from any major traffic arteries. Most of its land is owned by private timber companies; there is little large-scale agriculture and no major industry.

Yet more than 200 of its people gathered on a hot day in July, 1980, to stop some construction in their county, standing up to 10 state troopers and two private armed guards sent to protect the building site. The site was slated to become a hazardous waste landfill, and the citizens of Heard County had come to see it as a serious threat to their health and safety.

On that day last year, the troopers exchanged heated comments with the crowd for an hour or so, then left. The two private guards, originally under the impression that they were guarding an oil rig, stayed on into the evening, until it was clear the people would not disperse. The guards left together; the crowd melted into the night. But the fight over the waste dump was only beginning.

In May, 1980, Decatur entrepreneur William F. Belote formed Earth Management, Inc. (EMI), to capitalize on the growing concern over where to store the tons of hazardous wastes produced in the southeastern U.S. each year. Belote hoped to build a landfill in Georgia to handle toxic wastes produced throughout the region. EMI targeted Haralson County as the most desirable location, but this plan ran into a major obstacle: Georgia House Speaker Tom Murphy, a Haralson County landowner. EMI contacted Murphy about the site; he recalls, “I just said I wouldn’t like it. I never heard another word about it.”

Within a month, EMI set its sights on a new location. Heard County is one of 16 Georgia Piedmont counties considered suitable for hazardous waste landfills, and soon — though it produces little waste itself — it was a target for the rest of the Southeast’s lethal products. The landowner, former state representative Hershel Parmer, granted EMI an option to buy 276 acres of Heard County land. The company quietly began preliminary investigations on the site.

EMI could not keep its work secret for long. In July, 1980, Heard Countians learned about EMI’s plans and began organizing opposition to the landfill. Citizens in the area were already aware of the dangers associated with such landfills; less than a year before they had fought off a dump promoted by a local firm.

Meeting at the town hall in the county seat of Franklin, local citizens agreed to band together to stop EMI. With the help of local physician Jack Birge, the group took over Georgia 2000, a dormant nonprofit corporation which had been concerned with health and environmental issues, and began holding meetings and researching hazardous waste landfills.

The organizers didn’t need to do much outreach in the community; everyone quickly took a stand against EMI. Twenty core members traveled across the county speaking several times a week about the landfill and drumming up support. Within a short time, over 900 of the 8,000 Heard Countians became members of Georgia 2000, and many others actively supported the cause. The group raised enough money locally to take on the massive anti-dump campaign. Christine Cook, secretary of Georgia 2000, says, “We’ve been passing the hat after talks at churches, town halls, anywhere we can speak. It’s all donations from individuals — people who care.” A large fish fry in Ephesus, near the proposed site, raised almost $2,000. A combined volunteer fire and emergency medical service in a small town in Alabama held a benefit for Georgia 2000, adding several hundred dollars to the coffers. A gospel sing raised more. A country-and-western singer sold several thousand copies of “The Heard County Song” and donated the proceeds to the effort.

Citizens responded to EMI’s work at the site by surrounding the area, carrying shotguns and hunting rifles, to prevent further entry of equipment. Earth Management maintained that it needed access to the property to fulfill requests for further hydrogeologic data from the Georgia Environmental Protection Division (EPD).

Soon after, EMI’s drilling rig burned. Residents deny that the rig burning was the work of local people. One nearby resident notes that an EMI truck was seen leaving the site just before the fire and jokes, “If it had been one of us, the truck [parked next to the rig] would have gone, too.”

However, state officials felt local citizens were responsible. EPD released EMI from the requirement for additional information, even though EMI’s one water table measurement showed that at least one of the proposed “secure” cells would be below water. Governor George Busbee dispatched state troopers to provide protection for EMI employees and supporters. This protection, locals say, consisted of weeks of harassment of the dump’s opponents — and by then virtually everyone in the area not directly connected with EMI was among them. Families on their way to church were stopped while troopers searched their cars. Local trucker Harold Cook charges that one employee of Hershel Parmer shot at anyone coming down the road near Parmer’s chicken houses. “This is a public road. People go by here on their way to church and would get shot at. Busbee never did anything about that.”

On September 17, 1980, EMI formally applied to the state for a hazardous waste landfill permit. According to the application, the facility would accept between 90,000 and 180,000 tons of hazardous waste per year from producers in Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Florida and the Carolinas. EMI claimed its plans reflected the most advanced landfill technology available. The company had conducted a geological survey purporting to show that the selected site was suitable for a chemical waste “secure landfill.” According to the proposal, the site would not accept radioactive, explosive, shock sensitive or pyrometric materials, but would take highly toxic, infectious, teratogenic and mutagenic substances such as arsenic and pesticides. EMI made no plans for testing substances before they entered the dump, although such testing is essential to screening out unacceptable substances and to preventing fires caused by the mixing of incompatible wastes.

Local citizens quickly uncovered the proposal’s defects. Georgia 2000 sent copies to various experts, including Dr. Robert Cook, a noted geologist at Auburn University. Cook — a supporter of landfills in general — gave the Georgia 2000 activists some lively ammunition by pointing to defects in the design of the containment cells, the monitoring control of surface wastewater and other geological problems, all of which he felt “indicate a potential for long-term environmental damage.”

With support growing and technical evidence on their side, Georgia 2000 sought legal ways to block the facility. Under pressure from many of his constituents, County Commissioner Wayne Miller condemned the 276-acre site on September 26, 1980 — six days before Parmer was to transfer the title to EMI. Basing its action on the right of eminent domain, the county announced plans to develop a comprehensive recreational park on the site. Though such an act was virtually unprecedented, Georgia 2000 members were determined enough to try extreme tactics to win their point. EMI appealed the condemnation to a local court, charging that the condemnation’s sole purpose was to prevent the establishment of a hazardous waste facility.

At the same time, six landowners filed suit against the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, EPD and its director, Leonard Ledbetter, and Earth Management. Georgia’s constitution grants complete control of solid waste disposal to the counties, but the state’s 1979 Hazardous Waste Management Act strips local governments of any control over solid hazardous waste disposal. The landowners argued that the act was unconstitutional and that EMI had no right to open a landfill without local approval.

By October 27, 1980, when EPD held a public hearing on the proposed landfill, community opposition had mushroomed. Georgia 2000 presented more than 3,000 signatures on a petition to “Stop the Dump.” Over 500 citizens attended the public hearing; testimony ran late into the night.

Despite solid local support, frustration was setting in among some of the activists. “The hearing was all for show,” complained Clyde Cook, new president of Georgia 2000. “They never intended to listen to us.”

Anti-dump organizers stayed with the effort despite their exasperation with the state. In November, voters elected a new county commissioner: Steve Lipford, an active member of Georgia 2000 who ran as a vocal anti-dump candidate. Lipford has aggressively opposed the site and rejected any notion of compromise with EMI. “The people of Heard County elected me to keep the dump out,” he emphasizes. “They’d run me out of town if a deal were ever made.”

Shortly after the election, residents felt the first flush of victory. A superior court judge dismissed the landowners’ suit against the state and EMI, but on November 11, 1980, a local court upheld the county’s right to condemn the site; the county then won in EMI’s appeal of this decision to the Fulton County Superior Court on December 18. In addition, EMI had not received the state permits necessary to be legally defined as an “existing facility” by November 19; this failure meant the site would be subject to complicated new EPA Resource Conservation and Recovery Act regulations and thus would be delayed indefinitely until those regulations went into effect.

These opening-round victories were clouded by threats of violence circulating in Heard County. Georgia 2000 members received threatening telephone calls from unknown parties. Boards with protruding nails were regularly thrown into driveways. “In the last phone call, this guy ‘reminded’ me that my two kids could easily be picked up coming home from school and beaten,” said one activist. Frightened but determined not to back down, affected members kept the threats secret to avoid any possibility of retaliatory violence.

In early January, a “firebomb” destroyed a small shack on Hershel Parmer’s property; Parmer and the media described the shack as a blacksmith’s shop worth $15,000. A trip past the property a few days later, however, revealed one anvil amidst an old iron bed and other junk. Mrs. Parmer admitted that the smithy tools had been there when the property was purchased and had not been used since. When volunteer firefighters arrived to put out the blaze, Mrs. Parmer held them off at gunpoint, refusing to allow anyone onto the property.

On February 17, the small grocery of Cramer Rogers, a major Georgia 2000 activist, burned to the ground. Rogers reported that a caller the previous week had warned, “We haven’t forgotten about you, and we are going to get you.” Although arson was ruled the cause of the fire, the police have no suspects in the case. Rogers was inadequately covered by insurance and lost around $15,000.

Despite such disasters, the Heard Countians persisted in their campaign to keep EMI out of the area. They soon got another significant boost: a highly professional critique of the landfill proposal which shot holes in many of the arguments EMI had made. On February 25, 1981, Heard County Commissioner Steve Lipford presented Governor Busbee with this study, prepared by the Center for Environmental Safety at the Georgia Institute of Technology. Among the findings of the study: Georgia taxpayers would have to bear “enormous post-closure care and maintenance costs” under the EMI proposal; the proposal provided for inadequate lab equipment and staff to analyze the wastes the facility would be accepting; and “based on prior landfill experience, surface and ground water will be contaminated and uncontrolled reactions between incompatible wastes will occur with the resultant possibility of toxic fumes, fires and explosions.” Georgia 2000 released the report to the press the next day, and new allies rallied to the Heard Countians’ cause.

With technical evidence on their side and with a continued determination present in the community, prospects look good that the EMI facility will never open in Heard County. EMI has appealed the condemnation suit to the Georgia Supreme Court; a decision is expected soon, and a ruling in favor of the county could effectively bar the dump from that site forever.

In June, Governor Busbee indicated that the state might look at other areas for hazardous waste landfills. “Hopefully we will be able to go to a more rural area that won’t affect as many people as Heard County,” he said. Johnny Adams sums up local feeling towards the landfill campaign: “You can push a man a long way and he’ll keep on backing up — until he’s home. And buddy, we’re home.”

The seeming victory on the home front has not ended Georgia 2000's efforts. The group is now running a statewide campaign to improve regulation of hazardous wastes and works actively with other citizen groups on a variety of environmental issues. The news media frequently reports the group’s point of view on events associated with toxic waste.

But improving the state’s waste management program has proved difficult. At least partially in response to events in Heard County, the 1981 General Assembly overwhelmingly passed a bill establishing a Hazardous Waste Management Authority and granting it complete power over the siting and operation of any facilities. The legislature adopted the bill in record time and, according to House Speaker Tom Murphy, the object was “to get the Heard Countians off our backs.” Under the new law it will be impossible for a county to condemn land targeted as a landfill site.

Further, the EPD — charged with enforcing the state’s regulations — remains reluctant to regulate vigorously. Certainly, EPD’s past performance warrants little confidence in the agency’s management capability (see box). In fact, many of the EPD employees have backgrounds in sanitary landfill management but little experience with significantly more dangerous hazardous wastes; however, they tend to see hazardous waste management in terms of sanitary landfill management and discount many of the concerns raised by citizens. And Governor Busbee, who places industrial recruitment at the top of his list of priorities, has promoted speedy establishment of landfills and a relatively lax waste management program as incentives to new industry.

However, Georgia 2000’s statewide educational and organizing work has prompted a strong spirit of resistance to the state’s waste management practices. During a recent two-day conference on hazardous wastes, state officials repeatedly emphasized that landfills were “the only option.” But other speakers and members of the audience shocked the state officials by questioning the need for landfills. One person demanded, “Does all this talk about ‘suitable hydrogeology’ mean that you [EPD] are refusing to look at incineration?” County commissioners and sanitary landfill operators expressed concern over a loophole that exempts small firms from reporting on their waste disposal practices; many of these wastes now end up in municipal landfills. Clearly, hazardous wastes have become a major issue across the state.

In the past few months, Georgia 2000 has provided technical assistance and support to other groups working on a variety of issues — for example: investigating a massive tree kill caused by a chemical firm in Flood County and documenting radiation hazards in two areas resulting from the state’s failure to monitor or clean up the sites adequately. The group circulates educational materials throughout the state and is working with a public access television station to produce a special on environmental problems in Georgia.

Heard Countians are also interested in helping others fight landfills. Recently, Georgia 2000’s newsletter, the Heard Voice, reported that the state is considering land in Jones County as a potential landfill site. Led by a local politician, citizens have already held a town meeting and now plan to block the landfill “in any way necessary.” Georgia 2000 has distributed copies of the Center for Environmental Safety study nationally; used by both state agencies and environmental groups across the country, it has proved very effective in calling into question the safety and rationality of hazardous waste landfills.

The fight against EMI's landfill has profoundly changed the lives of many Heard Countians; they have learned many lessons and are committed to putting the brakes on hazardous waste production as firmly as possible. As one Georgia 2000 member mused, “You know, when I go to buy something now, I really think about how much hazardous waste might have been produced by this one thing. Then I think, ‘Do I really need this?’”

Tags

Ginny Thomas

Ginny Thomas is a research consultant with 12 years of experience in health and related issues. She works part-time for Georgia 2000, representing the group before the legislature, state agencies and the news media. (1981)

Bill Brooks

Bill Brooks was raised and still lives in Jasper, Georgia, which is about 20 miles from the Georgia Nuclear Laboratory. About a year ago, he took a Geiger counter to the site, found excessive radiation levels and has tried to get the danger corrected ever since. (1979)