Blk Music: How It Does What it Does

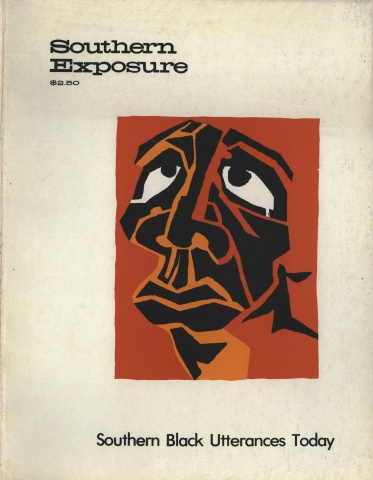

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 3 No. 1, "Southern Black Utterances Today." Find more from that issue here.

In the bulk of literature that exists on Afro-American music, not nearly enough has been said about the process of our music —how it is produced to do what it does and mean what it means. This dearth is the result of some obvious factors. One, for a long time our music was not deemed worthy of serious investigation. Two, the ethnocentrism of European and Euro-American investigators necessarily limited the nature of questions raised about the music and the kind of information sought. Three, since Afro-American music is performance-oriented and occurs typically within the context of an oral tradition, an improvisatory tradition, extra-musical questions are key. Only recently (thanks to the Western cultural bias) have the fields of kinesics, kinesthetics and musical therapy developed enough to offer some of the vocabulary necessary to even articulate the voluminous extra-musical features of our music. There are still "dormant" or "latent" areas to be developed that, again, will provide us with the vocabulary for clear musical review.

But for the most part, it is sheer ignorance about the aesthetic that governs Afro-American musical systems that is so depressing. Recently white critic Henry Pleasants argued in Serious Music and All that Jazz, "The jazz musician improvises time designated chords just as Bach and Handel did, the only difference being in the convention of chord designation .... The jazz musician has his own ideas and his own convention of melodic variation and embellishment, but the purpose and the procedure are identical with those of the Baroque musician." (Pleasants 50, emphasis mine).

Pleasants, in the grip of Euro-American centrism, is blind to the fact that the jazz tradition is fundamentally based on performance and improvisation. The European musical tradition he refers to is fundamentally dependent on the written score and the composer's intention. Clearly the jazz musician and the Baroque musician do not have identical purpose and procedure. The jazz musician will duplicate the material. Replication is key for the European, the process of collective transformation is key for the Afro-American.

The Afro-American musical process — a spiritualized interaction/happening between musicians first and then audience — utilizes particular features that characterize any number of aspects of our culture besides music: call and response, repetition, polyrhythms and polymeters, metronome sense and collective improvisation. The readiness of the musician to engage in the process depends on what went down in practice and prior performances. He/she practices to develop instrumental prowess/knowledge and the listening faculty.

We "practice" with or without our instruments, with or without music being played, in order to develop a particular listening ability: the ability to hear sound on the inside, from the inside, as well as from the outside. This in turn sharpens the anticipatory faculty —the ability to know/hear/guess where your fellow musicians are going. It enables us to retrieve from the inside the storehouse of sounds, riffs, relationships, harmonic textures and it summons up things never heard before. Armstrong, Fatha Hines, Tatum et al have all talked about trying to reproduce some statement, some sound, some performance in the head. Frequently, they reached it and/or discovered other new things in the attempt.

Like when I hear Coltrane, I recognize that the limits, the possibilities are further away than I had thought. Not simply the limits of the sax, but the infinite possibilities yet untapped but hinted at by where he's gone. When I listen to Kenny Baron, the changes, the ideas, the rhythmic attack and the accompanying choreography, so to speak, inform me of the gap that exists between where I am and where he is and the road that needs to be traveled. What he pushes the piano to do also hints at the open frontier up ahead of him. It's this that pushes one to master the instrument.

In addition to the development of the inner ear, one also develops kinesthetic response by internalizing the sounds and physical behaviour — which equals musical behaviour of other musicians. When I listen to Herbie Hancock's "Maiden Voyage," for example, I not only hear/absorb the harmonies, rhythms, colors, textures, etc., I also take it all into the muscle system. I see/feel/do the Hancock body movements. My hands play along. I hum along. I'm moved to interact with the feeling of it, the underlying assumptions that produced the music and the performance. I think this is what most of us do. When Freddie Hubbard takes his stance, which I "see" with my ear, it's inevitable that the body moves to mirror the cockiness in some way, to interpret the sensual buoyancy with the body.

I would suspect that most of us have the capacity to get totally involved with a performance by, say, Miles, Coltrane, Cedar Walton and so forth, while our involvement in a performance by Horowitz, Van Cliburn, Peter Duchin or Andre Previn is one-leveled, the experience thinner. It fails to trigger cultural flashbacks that can catch us up in a whole environment. Compare Gladys Knight's "The Way We Were" to the Streisand version, for example. Or recall the way the Coltrane-Elvin Jones dialogue in "Chim Chim Cheree" summons up the Baptist Church. Or the way kids will mimic character types while listening to the records. The Afro-American music process is one that engages the ear, the body, the memory, the experiences because it attempts to project a total living reality.

The cut "Maiden Voyage" will do to illustrate the previous point made about the characteristic features of the Afro-American music process: call and response, repetition, polyrhythms and polymeters, metronome sense and collective improvisation. The interplay between Hancock and Hubbard (when Hubbard solos), or Hancock and Tony Williams (when Herbie solos), recalls the call-response pattern of our sermons as well as our choral music, which is based on a prior knowledge/participation in that performance. Repetition—whose purpose in poetry, design and rhetoric, as well as music, is to emphasize, to increase tension — is observable in Hancock's accompaniment where the piano's response is a repetitive pattern. Its other purpose is to force the caller to resolve the tension of the repetition by either capping it or taking it off somewhere — the new call then becomes emphatic through contrast with the earlier call-response pattern. But it has another function. It allows the caller, who is engaged in improvisation, a moment to think of something else to play.

Throughout the cut we also hear overlapping call-response, the answer beginning before the last syllables of the caller's statement have ended. In contrast to these two possibilities, we turn to "The All Seeing Eye" where Wayne Shorter calls and Hancock's response is oblique; that is, he goes off to the side or further ahead, lays out a new direction. Obviously the oblique pattern gives little room for pause, requires some daring, certainly intensive listening.

Polyrhythms and polymeters are dependent upon one's metronome sense, one's grasp of beat. The particular use of upbeats in Hancock's opening statement of "Maiden Voyage" illustrates Hancock's as well as the group's metronome sense and "trains" the listening musician (always practicing) to develop his own. McCoy Tyner's "Saharah" is a lesson in polymetric expressions of 6/4, 4/4 and 2/4. The polyrhythms and polymeters exhibited in this cut harken back, of course, to the mother tradition— the African drummer. The use of polyrhythms allows the members of the group to create/resolve/abandon/ increase tension and to shape and reshape the density of the musical texture.

Collective improvisation, which has been an implicit aspect of our discussion all along, is both the goal and the path of our music-making tradition. It is the essence of Afro-American performance. The interaction of the soloist and the group, the internal interaction within the group, the interaction of the group and the audience. As a technique, an ideal and an occasion, collective improvisation offers the participants the opportunity for self-identity through self-expression within the context of the group. Contrasting any Afro- American performance steeped in the African tradition of collectivism with the performance of Afro-American musicians in a European context would yeild more in terms of understanding how endemic collective improvisation is in our music. The music of Nathaniel Dett, William Dawson and William Grant Still, for example, which utilize so many European forms and approaches ("purposes and procedures" as Pleasants might say) do not result in the realization of collective improvisation and therefore do not feel familiar or conjure up collective memory images, despite their integration of such Afro-American features as melodies. They made a decision to incorporate their Afro-Americanness (themes anyway) within a European frame to make their mark. (As might be expected, given the European music tradition, they were primarily composers and secondarily performers.) They made a class decision. Parker, Coltrane, Tyner and numerous others who were trained in, or trained themselves in, the European classical tradition, opted for another route. Rather than subsume the Afro-American in the European, they simply dealt with European sources as some among many.

The attitude "I am going to express myself on this tune" is a prerequisite for the successful appropriation/transformation of someone else's material. Participation in a culture that practices collective improvisation in so many areas activates that attitude, that drive for self-expression, trans¬ formation, inventiveness.

A concept borrowed from another discipline offers, I think, an approach to understanding Afro-American musical performance: continual flexibility in circularity. Dr. Wade Nobles, in conjunction with Dr. Sharon Brown, devised the concept to describe the dynamic functioning within the Black family —the fluid, flexible, interchangeable roles and functions of family members, the movement of concentric circles. Children as mothers, fathers nurturing, mothers assuming functions such as taking children to football games usually associated with fathering — in other words, the ability of each member of the family to do what others are "expected" to do both in conjunction with others and in their absence. There are no hard lines separating role functions but rather these are characterized by fluid and spiraling circles. In much the same manner, the five characteristics (call-response, etc.) rarely exist in a "pure" state and have rigidly defined purposes. It's the flexibility of each, the ability to combine/compound, to separate and rejoin that is the key to understanding the roles and functions that these techniques play in the Afro-American music performance tradition. The meaning of each depends on its interplay with others. Repetition is not just repetition, it is rhythmic, antiphonal, metronomic and encourages collective improvisation.

One of the primary goals of Afro-American musical performance, then, is the integration of the individual into the collective, by providing him/her with the opportunity for self-expression and interaction. Process, then, is the key to our musical aesthetic.

Tags

Ojeda Penn

Brother Ojeda, musician/composer/teacher, is a Ph.D. candidate at Emory University in American Studies, and is presently performing as pianist/percussionist in Life Force, an Atlanta-based group. He is also musician-in-residence at the Neighborhood Arts Center. (1975)