This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 1, "Building South." Find more from that issue here.

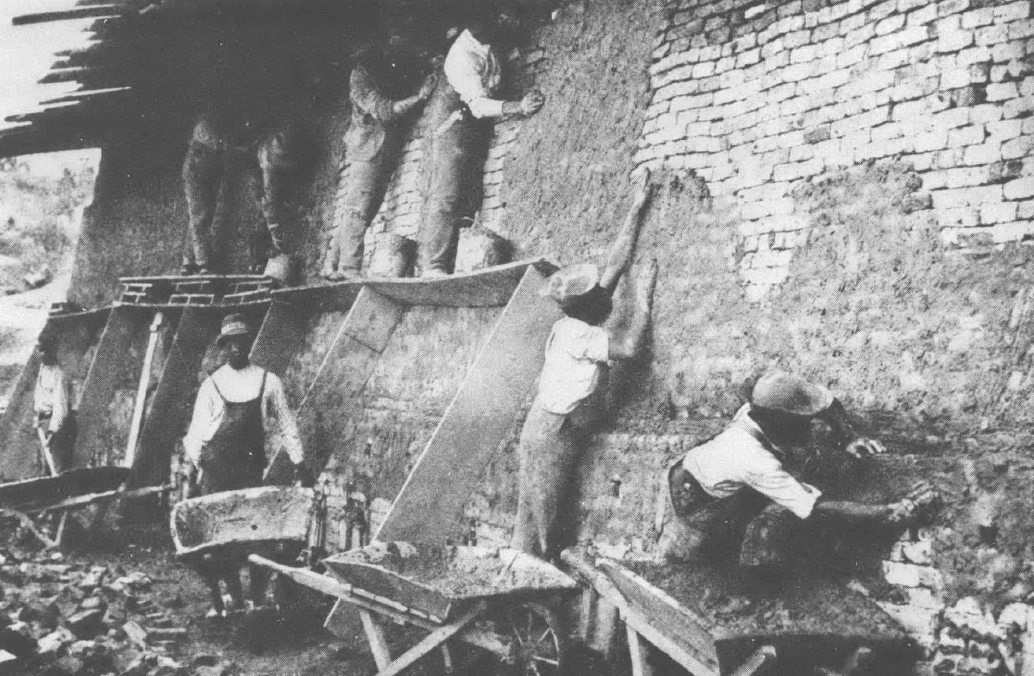

Writing in his autobiography, Booker T. Washington, the first principal of Tuskegee, stated: “From the very beginning, at Tuskegee, was determined to have the students do not only the agricultural.. work, but to have them erect their own buildings…

While performing this service [learn] the best methods of labour, so that the school would not only get the benefit of their efforts, but the students themselves would be taught to see not only the utility in labour, but beauty and dignity…Night school students worked at a trade during the day as did day students, once a week. Upper level students acted as foremen, and every student was required to work at a trade in addition to his academic work.”

The end of slavery re-arranged black artisans' place in Southern building. Their new status resulted from white tradesmen's reactions to low-paid competition and blacks' diminished opportunities to transmit cultural traditions and building skills. But while Jim Crow kept them out of many white unions and denied them lucrative jobs in the white community, black builders – in their own unions, in a few integrated unions, and outside unions – continued to ply their trades with superior skills based on years of antebellum experience.

In contrast to many unions, the bricklayers, masons and plasterers unions the "trowel trades" maintained a nondiscrimination policy rooted in the virtual monopoly blacks had on those fields. By World War II, only three segregated locals existed in the South, albeit in three major cities: Richmond, Atlanta and Charleston.

The Carpenters Union was far more typical. Founded in 1881, the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners had 14 totally black locals by 1886, with workers in these locals restricted to jobs within generally impoverished black communities. Separation between black and white carpenters was so complete that when not enough white workers were available for a job, the white local would call in out-of-town tradesmen rather than turn to local black carpenters.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, Jim Crow's hold over the construction trades solidified. Blacks were denied jobs, training and union membership by various underhanded means and by more "legitimate" methods like the fraternal system, which required applicants to be endorsed by someone already in the union. A. Philip Randolph observed that a black man "cannot get a job unless he has union card and he cannot get a union card unless he has a job."

During the late 1950s, the newly merged AFL-CIO maintained that its attempts to integrate the building trades and attract blacks would have to be gradual in the face of decades of segregation. Many black leaders charged that the trade unions dawdled on desegregation in order not to antagonize the white Southerners who were then the target of organizing drives. The unions' recalcitrance and resulting pressure from civil rights activists helped enact Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act which made union discrimination illegal. Soon after the act passed, the AFL-CIO began compliance; in 1968 its Building and Construction Trades Department established programs to recruit qualified blacks for apprenticeships and to remedy "deficiencies affecting the full qualifications of Negroes." Within 10 years this program recruited nearly 50,000 minority group apprentices, and placed 23,000 in skilled trades. Since one-fifth of all construction is federally supported, the government has played a key role in demanding equal employment opportunities in construction trades.

In the South, however, blacks are still confined to construction's lowest-paid jobs, with three out of four employed as laborers. Conversely, blacks make up less than five percent of the electrical workers and plumbers in the South. The Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway project, where blacks form a significant portion of the workforce due to the AFL-CIO's efforts and the government's employment guidelines for contractors, does not employ a single black electrician.

Of almost 1.5 million construction craft workers in the U.S., only 7.5 percent are black. The average family income of white workers is over $2,000 more than that of black workers' families. Blacks have proportionately fewer year-round jobs than whites in this highly seasonal industry and are frequently the victims of discrimination in apprenticeship programs, promotions, suspensions and firings. Programs to recruit black tradesmen failed to educate white workers about racism, and many unions had to be coerced into moving against segregation.

Yet some progress has been made. Blacks now comprise 8.8 percent of building trades union members. And integrated construction unions may be able to pursue a more aggressive organizing drive against New South open-shop employers, appealing to black workers as well as white.

Tags

Darryl Paulson

Darryl Paulson teaches political science at the University of South Florida. (1980)