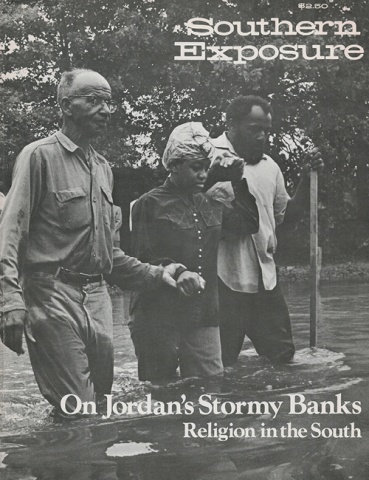

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Back at the turn of the century, when hundreds of itinerant preachers worked “the sawdust trail” to standing-room only crowds, evangelism meant miraculous healings and mass conversions in tent-meetings. Hell-fire and brimstone oratory poured forth from an army of men and women mobilized to beat the devil. As a result of their insatiable appetite for publicity, evangelists soon acquired a reputation as Bible-thumping, hysteria-prone, super salesmen for God.

Many years have passed, and the number of communities able to point to a successful tent-meeting in recent memory is small indeed and getting smaller. But the image has prevailed. Until recently. One man, and a Southerner at that, has done more than any other single individual or organization to recast that image in a form more acceptable to modern American culture. Though firmly rooted in the hell-fire and damnation school of Southern fundamentalism, William Franklin (Billy) Graham Jr. has exchanged the shirtsleeves and histrionics of the ‘Hot Gospeler’ for the tailored business suit and toned-down eloquence of a religious moderate and political conservative.

Yet Billy Graham has hardly renounced his heritage, in fact, the organizational techniques and sophisticated public relations methods employed by Graham and the association that bears his name (The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association) stand as proof of the huge debt which he owes to the rich legacy of the evangelists and evangelism of an earlier age. Mass revivalism on a national and international scale was a highly developed exercise by the time Graham had spiritually come of age. Even before he was born, Reuben A. Torrey, successor to noted evangelist D.L. Moody, had successfully concluded a four-year campaign which packed the largest public facilities available in China, Australia, India, and the British Isles, and netted 102,000 converts to Christianity in the process.

One of the most significant features of Torrey’s approach was his adroit use of community leaders. In each of the cities targeted for a crusade, the evangelist established “executive committees” of socially prominent laymen. The committees raised money for the evangelistic campaign and used the status of their members to gain free coverage from the press and enthusiastic endorsements from sympathetic pulpits.

In Chicago, Henry P. Crowell, president of the Quaker Oats Company and a trustee of the Moody Bible Institute, organized The Layman’s Evangelistic Council to lead the Torrey crusade. At the top of the stationery used by the committee, Crowell had printed the explanatory note, “A Businessman’s Movement.” The Council had charge of everything connected with the crusade, save the actual delivery of the sermon. Graham learned from later revivalists that a full-time staff was more dependable, but he still relies heavily on wealthy, powerful businessmen to provide the financial and moral support so necessary to his crusades. As we shall see, under Graham evangelism continues to be “a businessman’s movement.”

Eventually, Torrey became concerned about the growing commercialization of the crusades; Charles Alexander, his soloist and chorister, was making a mint from sales of his songbooks (selling songbooks, records, and books by Billy Graham continues to be a regular feature of his crusades) and the different approaches to finances led to the end of the Torrey/ Alexander team in 1908. Alexander immediately joined John Wilbur Chapman and the Chapman Simultaneous Evangelistic Campaign.

Chapman spent 10 years mastering the technique and enjoyed varying degrees of success. But soon Chapman’s crusade no longer drew the large crowds or prestigious invitations. A new star had appeared on the horizon, young and more dynamic than any who had gone before him, the man whose name was to dominate evangelism for the next fifteen years — Billy Sunday.

Sunday’s style was remarkably similar to Billy Graham’s early “windmill preaching.” Sunday would run up and down the stage, telling Bible stories in popular language with a hoarse, rasping voice, challenging members of his largely lower-middle-class audience to “be a true patriot” or a “manly man” and make a decision for Christ.

And like Graham, Sunday tried to keep the emotional pitch of his audience at a manageable level. He discouraged people from yelling even simple ‘Hallelujahs’ or ‘Amens’ and instructed his ushers to remove those who insisted on continuing these relatively mild emotional indulgences. Sunday was evangelism’s top showman and he didn’t want any competition — not even from his own audience.

At the heart of Sunday’s revival corporation was the Sunday Party, a corps of more than 20 experts, each of whom specialized in some aspect of revivalism. The members of this Party were called directors, and most of them had assistants. Many of these directors and assistants were in charge of organizing delegations from various constituencies in the community and bringing them to the crusade. Sunday’s staff and volunteer canvassers would grant blocks of reserved seats for any group that requested them in advance, and the staff made sure there were plenty of requests. Every night of the crusade there would be as many as 50 delegations on hand, some as large as 3,000. Homer A. Rodeheaver, Sunday’s chorister, would warmly welcome each delegation and would then have them compete against each other during the singing program. By the end of the service, when Sunday appealed to each delegation to step forward, entire delegations often made the trip up the center aisle. The same delegation system is still used very effectively by Billy Graham.

Sunday gradually lost touch with his audience as his attacks against the ‘decadence’ of the Roaring ’20s became more irrational and extreme. By the end of his career, Sunday’s message had degenerated into pessimistic resignation and a conviction that the Second Coming of Christ was the only hope for the human race. His constituency dwindled, and he was reduced to working one-church revival services in small rural towns like his birthplace of Ames, Iowa.

Anointed to Preach

Graham gave his life to Christ at a revival led by Mordecai Fowler Ham, a fire and brimstone evangelist who had made his reputation in the South during the Depression. Graham’s father, a strict Presbyterian, had helped organize the revival on some farmland just outside of Charlotte, N.C., Graham’s birthplace.

The story of his conversion is important in understanding the way he structures his services today. In an interview with Myran Blyth in Family Circle, she described the incident: “There’s a great big sinner in the church tonight!” (said Ham). The boy blushed, ducked behind a woman in a big hat and thought, “Omigosh, my mother must have told him I was coming.”1 At the end of the service, Graham, moved as much by feelings of guilt and shame as by his love for Christ, went forward to give his life to God.

Like Billy Sunday, Graham’s conversion experience was fairly calm; not a single tear was shed by the sixteen year old when he went forward that night. And like Sunday, he re-creates his conversion experience at his crusades today, relying on a message that is often riddled with remarks that Graham has consciously chosen to make the individual sinner in the audience feel his or her burden so heavily that they must come forward and have it lifted. The atmosphere is solemn, heavy with the “presence of God”; though the emotionalism isn’t as theatrical as Billy Sunday’s, the effect is just as powerful.

Graham graduated from high school in 1936 with no particular career ambitions. He had seriously considered attending the University of North Carolina, but his mother, a deeply religious woman, had decided that he should go to Bob Jones College in Cleveland, Tennessee (now Bob Jones University in Greenville, South Carolina).

The summer before Graham left for Bob Jones, he joined the summer sales staff of the Fuller Brush Company. His experience selling door-todoor had a tremendous impact on his career. Before that summer, he had considered himself a bit shy with strangers and was uncertain of his speaking abilities. But when he broke all sales records for his area, he found new confidence in his general personality and presence. Many years later, that same sales ability exerted for the Lord’s gospel instead of Fuller’s brushes, prompted the Sales Executive Club of New York to dub Graham “Salesman of the Year.”

Disturbed by the lack of athletic facilities and the constraints upon independent thought and lifestyle, Graham left Bob Jones after only one semester, and transferred to Florida Bible Institute (now Trinity College), where he had the freedom to mature at his own pace with individual guidance and counseling from faculty and staff. He changed from a happy-go-lucky, gangly boy to a young man determined to be “an ambassador for God.” And he met evangelicals like Homer Rodeheaver (Sunday’s enterprising musician), Gypsy Smith, and W. B. Riley. John Pollack, Graham’s official biographer, describes Graham’s meeting with these leaders as an anointing: “These old stalwarts who had seen the fires die down had one theme: we need a prophet. We need a man to call America back to God.”2 Under new tutelage, Graham began to preach everywhere he could — on street corners, in small churches, or to the stumps and alligators at a nearby swamp. He would often preach seven or eight times in one day, coming home thoroughly exhausted. He pursued his studies seriously, determined to get a firm grounding in the Bible.

The Florida Bible Institute was a small school and, in his new passion for knowledge, Graham soon exhausted its resources. Consequently, when he was offered a free year’s room, board and tuition at Wheaton College in Illinois, he decided to move north. But before leaving the South, he became, with his parents’ approval, an ordained Southern Baptist minister.

During his stay at Wheaton, Graham met Ruth Bell (daughter of Dr. Nelson Bell), who was to have a moderating influence on Graham’s religious beliefs. As Pollack notes, “Ruth and her family, loyal Presbyterians, eased Billy Graham from his unspoken conviction that a vigorous Scriptural faith could not dwell within the great denominations.” Graham’s most important lesson from Wheaton and the Bells was “that any minister who was a strong evangelical should focus his vision on the entire horizon of American Christianity.” It was 1943, the year Youth for Christ International was founded. Graham had abandoned doctrinistic fundamentalism, but still retained his earlier style.

He plunged into his evangelistic career with the same energy and dedication he showed his studies. Torrey M. Johnson, another Wheaton graduate, gave his popular Chicago radio ministry, “Songs in the Night,” to Graham and his Village Church. Graham convinced George Beverly Shea, a well-known Christian soloist and broadcaster to assist him and the show soon became popular enough to pay for itself.

At the invitation of George M. Wilson (now executive vice-president of the BGEA), Graham began to work with the Youth for Christ movement. For three years, he gained valuable experience as field representative for Youth for Christ, organizing and speaking to rallies ranging from 3,000 to 5,000, traveling to Europe, and meeting the leaders of the National Evangelistic Association, which strongly supported Youth for Christ.

Then, W.B. Riley, a frequent visitor to Florida Bible Institute, asked Graham to accept the presidency of Minneapolis-based Northwestern Bible School. Riley had found his prophet. Graham had reservations about becoming associated with the orthodox fundamentalist but took the offer any- way. However, Graham rarely spent his energy exercising the presidential duties. He left the school in the hands of George Wilson and others while he continued to devote most of his time to evangelism.

In spite of all this activity, Graham still didn’t have a regional following, much less a national audience. He had long thought of himself as a poorly educated Southerner, lacking poise and sophistication, and felt that this placed definite limits on the potential effectiveness of his ministry. At times, he seemed almost resigned to the mediocrity seemingly imposed by his "indifferent background.’’ But, after his 1949 Los Angeles crusade, he never had to think about that again.

The Big Crusade

The Los Angeles Crusade had run for three weeks and though it was time to fold the tent, many of the staff protested, citing the rising attendance and interest. Graham decided to wait for a ‘‘sign’’ from God, a "fleece” that would convince him that it was God’s will that the tent revival continue. The sign came from Stuart Hamblen, a famous singing cowboy, but it would be hard to call it a miracle.

Graham met Hamblen before the revival started at a meeting of the Hollywood Christian Group. Graham was attracted to Hamblen and because Graham was a Southerner, Hamblen took a liking to the earnest young evangelist, inviting him to appear on his radio show, and encouraging people to attend the crusade, saying, “I’ll be there, too.”

Hamblen attended with regularity, but soon began to feel defensive about the content of Graham’s sermon. Hamblen believed the evangelist’s sermon, his standard fare about the sinner in disguise, was aimed straight at him. At the last night of the crusade, as Graham said, "There is a person here tonight who is a phony,” Hamblen shook his fist at his erstwhile friend, and stalked out of the tent. But the power of Graham’s method was clearly evident in the events which followed. In a sudden reversal, the singing cowboy called Graham at two o’clock the next morning and came over to his apartment. By 5 a.m., Hamblen had given his life to Christ.

The effect was sensational. Hamblen told his radio audience that he had given up smoking, drinking, and horse racing, that he had given Christ control of his life, and that at the invitation he was going to "hit the sawdust trail.”

Jim Vaus, a high ranking accomplice of underworld czar Mickey Cohen heard Hamblen on the radio and decided to stop by the tent and see just who this Graham fellow was. Vaus accepted the invitation the first time he attended, providing Graham with more free publicity.

Louis Zamperini, a 1936 Olympic star who had since become a penniless, heavy drinker, attended the revival at the request of his Christian wife and went forward at the invitation.

In addition to individual guilt, Graham preached a message that took advantage of the Cold War sentiment in his California audience: "Russia has now exploded an atom bomb. Do you know the area that is marked out for the enemy’s first atomic bomb? New York! Secondly, Chicago; and thirdly, the city of Los Angeles. Do you know that the Fifth Columnists, called Communists, are more rampant in Los Angeles than any other city in America? We need a revival.”

William Randolph Hearst heard about the famous converts and Graham’s warnings and sent a telegram to the editors of all Hearst newspapers ordering them to “Puff Graham.” Henry Luce, the publisher of Time, Life, and Fortune, was so impressed with the message, according to a Graham aid, that he “pledged the cooperation of his magazines to support subsequent Graham campaigns in other cities.” The Graham crusade was becoming a national media phenomenon.

The next five years were a dynamic period for the North Carolina native. He started his Hour of Decision radio program, founded the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, held successful tours all over the country and was publicly seen and photographed with some of the most famous people in the United States. The lesson of Los Angeles had not been lost.

But Graham still hadn’t matured as an evangelist. Stanley High, another biographer, described his early preaching style as “pretty much in the tradition of the ‘Hot Gospeler.’ His voice was strident. He inclined to rant. The same sound effects in politics would, in most places, be called demagoguery.”

Indeed, Graham’s sermons of that period often smacked strongly of demagoguery. In a 1953 radio sermon on “Labor, Christ, and the Cross,” he said, in an obvious reference to McCarthy, “I thank God for men who in the force of public denouncement and ridicule go loyally on in their work of exposing the pinks, the lavenders, and the reds who have sought refuge beneath the wings of the American Eagle and from that vantage point try in every subtle, undercover way to bring comfort and help to the greatest enemy we have ever known — Communism.”

Willis G. Haymaker, an advance man for Gypsy Smith, Bob Jones and Billy Sunday, had been with the Team since 1950 and introduced many changes in the Team operations. He organized prayer meetings before crusades, coordinated publicity, and taught the basic facts of organization.

According to William McLoughlin, author of an extensive study of revivalism, Graham’s image “ . . .shifted from the Hollywoodish, flamboyant revivalist in the direction of the conservative, but fervent, Protestant minister. His crusade atmosphere became less like that of a circus and more like that of a cathedral. He .. . directed his associates to keep up with the best means of advertising, office efficiency, promotion, small group evangelism, and follow-up.”

The real test of the Team’s growing organizational expertise came in New York in 1957. In the course of the three and one-half month crusade, 61,148 inquirers came forward from an audience of 2,397,000. Follow-up work, guiding and directing people who have decided to follow Christ, became unmanageable. The Team acquired the services of former Air Force Colonel Bob Root, who eventually organized the follow-up procedure.

The success of the New York crusade, highly visible in the American media fish bowl, firmly entrenched Graham as a national religious figure and celebrity, establishing him as the friend of politicians, religious luminaries, sports stars, etc. After the New York success, the challenge was to expand and deepen his organization and public support.

The Medium of the Message

Crusades, the source of Graham’s support and publicity, are masterpieces in the application of the latest techniques in public relations and organization.

Once Graham decides to accept a city’s invitation to conduct a crusade (usually one to two years before the projected opening date), an advance group goes to the city and begins to mobilize every Protestant church willing to support the effort. An executive committee is established (a la Sunday) and ministers of the participating churches are appointed to a variety of committees.

In his early career, Graham, like Sunday, made sure a sum large enough to cover costs was pledged by private subscription as a guarantee should offerings during the crusade fail to bring in the needed support. Crusade expenses have since soared to over $1 million and now Graham supplements local offerings with television and radio appeals and direct mail solicitations.

Graham has pioneered work in follow-up of inquiries, publicity and financing — the three most controversial aspects of mass evangelism. Follow-up is done by a group of young Bible school students called the Navigators who work in a city up to six months after the crusade has ended, trying to connect “inquirers” with a local church.

Publicity has been developed to the highest possible degree, using every conceivable means. Thousands of volunteers conduct door-to-door canvassing operations, mobilizing the local church community (and involving them in the success of the crusade) and spreading the word that Billy Graham is coming to town. And when he broadcasts over television, he blacks out the local area to insure high attendance.

After successful crusades, public explanation for success is that the Spirit of the Lord, working through Graham, his Team, and the local churches provided the inspiration to reach new converts and backsliding Christians. Any reference to the importance of a highly efficient organization is saved for private interviews. But God has never taken any of the blame for those crusades which fell short of their goal.

In kind, Graham’s entire crusade apparatus rivals that of any multinational corporation.

The Hour of Decision, Graham’s weekly radio program, started in 1950 at the suggestion of Fred Dienert and Walter Bennett of the Walter Bennett Advertising Company. Prompted by a $2,000 gift from two Texas friends, Graham decided to make the additional $23,000 he needed to begin broadcasting a “fleece” for his Portland crusade, stipulating that the $23,000 had to be raised before midnight. Graham took the regular offering, not mentioning the radio program; after the money had been collected, Graham told the audience he needed $25,000, inviting those that wished to contribute to meet him in the office at the end of the service. The draw of meeting Graham personally probably had as much to do with the long line as the appeal to higher Christian service. At the end of the night, Graham had $23,500, including the $2,000 from the sympathetic Texans. When he returned from the crusade, he found $1,500 in pledges waiting at the hotel from people unable to stand in line, giving Graham the $25,000 and a new radio ministry.

Due to income tax laws, Grady Wilson couldn’t put the money in the bank under his name or the Billy Graham Radio Fund. George Wilson (no relation) flew from Minneapolis with articles of incorporation for a nonprofit Evangelistic Association that he had drawn up over a year ago, foreseeing the need for such an organization. Billy and Ruth Graham, Grady Wilson, Cliff Barrow, and George Wilson signed the papers to create the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA). Graham asked for a radio ministry and got an institution, too.

Today the Hour of Decision is aired by over 900 stations around the world (including the one owned by the BGEA in Honolulu, Hawaii).

The Good Word is also spread through Graham’s “My Answer” syndicated newspaper column appearing in 200 dailies, through purchased television broadcasts of the crusades, and through the distribution of films produced by the BGEA World Wide Pictures based in Burbank, California.

The monthly magazine of the BGEA, “Decision,” now has a circulation of 5,000,000 (at $2/year)3, a sizeable increase from the initial run of 253,000 in 1960."Decision” promotes Graham’s theology, runs testimonies of the saving grace of Jesus Christ, solicits funds, sells books, and reports on the activities of Graham and the associate evangelists.

Books, phonograph records, and radio-sermon leaflets are distributed by the Grason Company, a taxable business started in 1950. The BGEA cannot legally distribute these materials, but Grason donates its profits to the Association.

Finally, there are the crusades. Graham has reached approximately 80 million people through his revivals where he peddles materials like the “Authorized and Authentic Biography of Billy Graham,” “Billy Graham Songbook,” and the thirteen books he has authored.

The BGEA employs over 300 people worldwide with headquarters in Minneapolis and offices in Paris, London, Hong Kong, Sidney, Winnepeg, and Atlanta. The staff has grown to seven associate ministers and five full-time musicians. The BGEA has an annual income of $14 million controlled by Graham and a 25-member board of directors that meets four times a year (the seven person executive committee meets once every six weeks). No director receives monetary compensation. The BGEA would not divulge the names of the people on the board saying “it might create too much of a hassle for the directors to have their names made public. ”4

The proceeds from all the “ministries” provide the bulk of the income for the Association, the rest coming from direct mail solicitation and anonymous gifts. The Association also uses this income to pay Graham’s $25,000 salary. He has always been sensitive to criticism of personal profit from preaching the gospel; consequently, he has let it be known that “I personally do not receive any money, honorarium or stipend for any of my appearances anywhere in the world. My annual income is solely from a salary paid by our corporation in Minneapolis and by royalties from my books.” The royalties are no small sum: “Secret of Happiness (1955) has sold 906,357 copies; World Aflame (1967) 1,027,976, with an additional special run of over 600,000.”5 Graham keeps a percentage of the royalties and donates the rest to the Association and other religious organizations.

He can well afford to be benevolent. The Association pays all his travel expenses; he receives free food and lodging at Hilton hotels; he often receives chauffeured cars from Ford Motor Co., and he has received gifts ranging from a jeep to a new home in the mountains of North Carolina.

Apparently the size of the organization and the comfortable affluence Graham has attained hasn’t reduced his personal involvement or interest in the operation of the Association. “Billy Graham receives daily reports by telephone. Each month he runs his eye down the list of checks, large and small, paid out from every office, and asks for the detail of any he can't understand.”6

Politics and the Preacher

Carl Mclntire is more rabidly anticommunist, Bob Jones more harshly critical of liberal ministers, and Garner Ted Armstrong more apocalyptic, but Billy Graham is more influential and his politics are, essentially, as conservative as the other gentlemen above.

The recurring theme in Graham’s political statements is, "Yes, do good works, but winning souls to Christ is more important.” John Pollock says Graham is “‘more convinced than ever before’. . . that we must change men before we can change society. . . . The task of the evangelist is not merely to reform but to stimulate conversion, for conversion puts man in positions where God can do for him, and through him, what he is incapable of doing himself.’”7 Graham restated the same theme in World Aflame: “If the church went back to its main task of preaching the Gospel and getting people converted to Christ, it would have far more impact on the structure of the nation.”8

An example of this logic comes from Billy Graham Speaks: “Reno can give you a quick divorce, but Christ can give you a quick transformation in your home. The tempers that have flared, the irritations that are evident, the unfaithfulness that is suspected, the monotony and boredom of existence without love can be changed and transformed in the twinkling of an eye by faith in Jesus Christ. ”9

This optimism barely surpasses his patriotism; Graham believes that “America is the key nation of the world. We were created for a spiritual mission among nations. . . . America is truly the last bulwark of Christian civilization. If America fails, Western culture will disintegrate.” He strikes the same note on a personal level in his sermons: "If you would be a true patriot, then become a Christian: If you would become a loyal American, then become a loyal Christian.”10

Three of the most influential social movements in the past twenty-five years have been the civil rights, antiwar, and women’s movements. The first two shook the conscience, structure, and politics of the nation and the third is still being hotly debated. Graham has definite opinions on all three.

In the early and mid-50s Graham took a moral stand towards the issue of integration in his crusades. By 1953, he would not allow segregated seating, even in the South, opening himself to attacks by more closeminded evangelicals. He changed the site of the 1954 Columbia, South Carolina, crusade from the segregated statehouse grounds to federal property to have an integrated rally. Ten years later, however, he was on the conservative end of the civil rights question. He deplored boycotts, marches, and protests stating “the position he has maintained consistently: conciliate, and strike at the root of the problem, which is basically spritual.”11 Graham seems incapable of understanding the need for struggle outside of that required to become a better Christian and resist the temptations of Satan.

Graham’s conviction that communism is the work of the Devil laid the foundation for his unequivocal support for the war. At a 1966 Presidential Prayer Breakfast, Graham made it clear that his Christianity helped his support for the slaughter in Southeast Asia. “There are those who have tried to reduce Christ to the level of a genial and innocuous appeaser; but Jesus said: ‘You are wrong. I have come as a fire setter and a sword wielder.’ He made it clear to them that His coming, far from meaning peace, meant war. . . .Those who hate tyranny and aggression will take sides when little nations suffer terror and aggression from those who seek to take their freedom from them. To preserve some things, love must destroy others.” Perhaps this is why John Connally has called Billy Graham “the conscience of the nation.”

Since then Graham has made the typical excuses that his stance only reflected the mood of the nation at the time, that he couldn’t possibly have known Vietnam would become such a divisive, bitter, embarrassing question among Americans. But that is exactly the point. Graham keeps a wet finger to the wind of the powers that be, only mellowing his position on Vietnam when it was comfortable and acceptable for him to do so. The opportunism and lack of morals he demonstrated on this issue is one of the most graphic examples of the true role Graham plays in our society — legitimizing the war policy and ingratiating himself to its leaders.

On the question of women’s rights Graham relies on a literal interpretation of the Bible. God created man and then women with a definite plan for each. “The biological assignment was basic and simple: Eve was to be the child bearer, and Adam was to be the breadwinner. Of course, there were peripheral functions for each, but these were their fundamental roles, and throughout history there has been very little deviation from the pattern.”12

He makes it absolutely clear that he does not support the women’s movement. “I believe the women’s liberation movement is an echo of our overall philosophy of permissiveness.” Since Graham doesn’t believe the women’s movement is constructive, he points to the Bible and its three-part plan for woman in society. “Eve’s biological role was to bear children — ‘in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children’ (Genesis 3-16). Her romantic role was to love her husband — ‘Thy desire shall be to thy husband’ (v. 16). Her vocational role was to be second in command — ‘and he shall rule over thee.’ (v. 16)” That, says Graham, is true freedom. “God frees us to be what we are created to be —each with a separate identity and purpose, but both sexes one with God. That is true liberation.”

Billy Graham is not unmindful of his own special identity and the freedom that comes with courting the rich and famous. The acquisition of wealth is required by salvation because it is a powerful means of benefiting others. Private gain donated to the great crusades can lead one to believe that the exercise of private and personal virtues is the totality of public responsibility.

His roots are in Southern fundamentalism, but he has built upon that foundation a vast smooth-running corporation that adapts to the social and political climate of the American status quo. In so doing, he has gained what his evangelical forebearers never did: respectability — and a carefully calculated plan for his own organization’s survival.

1. Myrna Blyth, “An Interview with Billy Graham,” Family Circle, April, 1972, p. 72.

2. John Pollock, Billy Graham, The Authorized Biography (New York: McGraw- Hill), 1966, p.16.

3. Lois and Bob Blewett, Twenty Years Under God, (Minneapolis: World Wide Publications), 1970, p. 127, and from an interview with Don Bailey, executive assistant with the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (Atlanta office), September, 1976.

4. Interview with Don Bailey.

5. Blewett, p. 127.

6. Pollock, pp. 243-244.

7. Ibid., p. 222.

8. Ibid.

9. Cort R. Flint, Billy Graham Speaks (New York: Grossett and Dunlap), 1966, p. 62.

10. “Our Bible,” Sermon distributed by the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

11. Pollock, p.224.

12. Billy Graham, “Jesus and the Liberated Woman,” Ladies Home Journal, December, 1970, p. 42.