This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 1, "Building South." Find more from that issue here.

Over the years, his name became a household word. You could tell a Jim Walter house, the same way you could instantly pick out a Chevy sedan in a car lot-sea of Pontiacs. Small, simple and Spartan, they were built mostly in the country or in small towns. To thousands of blue-collar Southerners, men and women who might not have had much money but who had steady jobs and owned pieces of land, Jim Walter offered a house which was clean and decent even if it wasn’t fancy. Jim Walter offered them low prices, a chance to save more money by doing part of the work themselves, instant financing, and a mortgage which could be paid out in a few years — “Ask yourself,” Jim’s salesmen always said, “how old would you be after you had paid a 25- or 30-year mortgage?”

The House That Jim Built

More than 200,000 Jim Walter houses have been built now, and almost 10,000 more are added each year through a sales network of 108 offices in 20 states. The sales offices are invariably located on main roads just outside major towns. There, on small lots, three or four houses in varying degrees of completion await customer inspection. The basic house is a shell, completely finished on the outside but with the framing exposed on the inside. In the beginning, that was the Jim Walter house, but as competition in the shell industry increased, Jim Walter Homes began offering more completely finished houses to higher-income buyers.

Ninety percent is still as nearly completed as you can buy a Jim Walter house, but now only a fifth of the total homes sold are shells. The buyers are still predominantly lower-middle class, but more and more Jim Walter houses are sold as second homes, built on recreation property in the mountains or at the waterfront. Jim Walter Homes says the average family income of its customers in 1978 was $14,750. This can be compared to a 1962 profile of Walter’s customers: average wage, $75 to $85 per week, mostly people who work with their hands, most of them buying a house for the first time, most of them paying monthly payments less than the rent they had been paying for substandard housing. In 1962, the top-priced fourbedroom Belmont sold for $3,495. If you visit a Jim Walter sales office today, the cheapest model is $11,900, and the top-of-the-line four-bedroom President averages $33,000 in North Carolina; prices vary from state to state.

Today the average selling price of all Jim Walter houses is $18,000, and the average monthly payment is $212. The company says that works out to 16 percent of the monthly income of its customers, “well under the generally accepted percentage of income spent for housing.”

Prices of Walter houses were increased five percent overall last year, but Homes Division vice president Bob Michael says this did not offset inflation in building materials and labor. Michael says profit-per-house thus declined, but the Division’s total profits increased because its yearly tally of houses built is climbing.

In fact, Jim Walter Homes, a company begun by a 23-year-old entrepreneur in 1946 in Tampa, Florida, is now the nation’s largest builder of single-family homes. More importantly, James Willis Walter has built his company into a conglomerate with interests ranging from building materials to coal mining.

Even if you never buy one of his houses, you have probably done business with Jim Walter. Imagine, if you will, a young couple walking hand-in-hand toward their dream home, regardless of the builder. The diamond on her hand could well have been bought at Lorch’s Jewelers, the stone on the patio from Jimco Stone Centers, the sewer line serving the house from U.S. Pipe & Foundry, the garage door from Jim Walter Doors, the gypsum board on the walls from Celotex, the mantelpiece from Georgia Marble, the bathtub from Briggs Plumbingware, the fireplace from Vestal Manufacturing, the doors to the kitchen cabinets from Gamble Brothers, the windows from Jim Walter Window Components, the medicine cabinet from Miami-Carey, the flooring from the J.P. Hamer Lumber Company, and the various screws in the house from Southeastern Bolt and Screw.

This imaginary couple might also be in debt to the Brentwood Savings and Loan Association and cook with electricity produced from coal mined by Jim Walter Resources and might use paper products from Jim Walter Papers. All of those are Jim Walter Corporation interests, giving the House-That-Jim-Built 1979 assets worth $2,049,000,000 and 1979 sales of $ 1,948,000,000. Walter’s position in the housing and building materials markets is strengthening, and he is increasingly moving into natural resources exploitation. The most recent addition to the corporate family is Jim Walter Metals, which is building a $27 million aluminum rolling mill in Mt. Holly, South Carolina. The plant is scheduled for completion in late 1980 and will produce sheet and foil aluminum and other products. In all, the Jim Walter Corporation has more than 25,000 employees, of which not quite half are union members. The union members work in mining and manufacturing. Since the company subcontracts all the actual homebuilding, it does not have any carpenters, roofers or other tradespeople on the payroll. So far as anyone knows, Jim Walter has never driven a nail in one himself.

If Horatio Alger Lived Today, He Would Be Called a Young Jim Walter

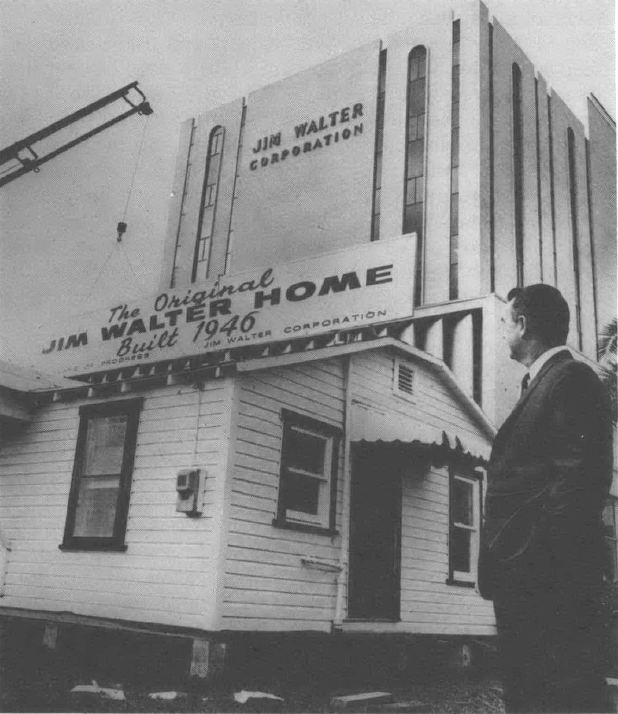

It is a long way from that first shell house to the Fortune 500 (1979 ranking: 169), and the story has been told so many times that at any moment on the road to Jim Walter corporate headquarters in Tampa, one expects to turn the corner and see that house bronzed like a pair of baby shoes, the house back on the twentieth anniversary of his company’s founding and displayed it for Jim Walter In fact, Walter bought a time next to the high-rise office building Walter put up in 1966. Still, the story is a good one and obligatory:

Jim Walter was 23, newly married and a Navy veteran earning $50 a week hauling fruit from Florida to New York when he spotted an ad in the Sunday Tampa Tribune one morning in 1946. “NICE little unfinished houses to be moved. $895. 9410 11th St. SS.” To Walter, who was living in a $50-a-month apartment and looking for his own home, the ad was appealing. After looking the house over, he borrowed $400 from his father and bought it. But instead of finishing the house, he sold it three days later for $300 profit and decided this was a more interesting and lucrative way to make a living than hauling oranges and grapefruits.

The builder of the original frame house was O. L. Davenport, also in his 20s, and Walter talked him into a partnership. Each put up $800 in capital and then they built two shell houses as samples and opened up for business. “I’ll never forget that Sunday if I live to be a million,” Walter says. He and Davenport stood in the doorways of their shell models and looked at the cars lined up the block, and inside they sat on nail kegs and talked things over with customers. By nightfall they had sold 27 houses for $1,000 cash each. Thus was born the shell house industry.

Walter and Davenport started at the right time, in the post-war housing boom of the late ’40s. Though VA and FHA financing was unavailable for unfinished houses, the government’s post-war promotion of private home ownership through the Housing Act of 1949 and other measures helped create a homebuying climate in which Walter thrived. Walter reasoned correctly that thousands of young veterans like himself were eager to buy their own home and were willing to invest sweat to replace the money they didn’t have. His houses also had intrinsic appeal to the working poor, people who were comfortable with tools and used to hard labor; they could use their lots for security and get four-year mortgages with no down payments for as little as $2,000.

To men like C.L. Stephens, who talked his father-in-law into giving him an acre of the family’s rocky 50-acre farm in Abanda, Alabama (population 85), Walter’s “easy credit” plan was the best deal around. There were no complications, no lawyers, no closing costs, no closing, even. It was all very simple. It was also simple when he got behind in his payments and Walter repossessed his home. Stephens lost what he had invested; his father-in-law lost the acre of land.

The shell home idea was as attractive to other builders as to customers; by 1960 there were 213 companies (including 31 in Atlanta alone) in the business. But in the 1961 recession the business went bust, undermined by near-saturation of the market and the financing methods the industry used for its houses. Like mobile home dealers, the shell builders provided their own financing, then sold the retail paper to loan companies. Many builders were lax about checking out the credit records of their customers before approving their loans and some companies even built on land which was itself mortgaged or had otherwise clouded titles. Jim Walter was more careful. His customers were and are carefully screened and he will not build except on land owned free and clear by the customer.

By the time the industry shakeout ended in 1962, Jim Walter was just about the only shell builder left, and even his business was changing as prices were increasing and the company was offering more-finished houses.

From One Tread Mill to Another

By 1961, shell homes accounted for about eight percent of all the single-family dwellings built in this country and most of them were sold on credit. While financing involved greater risk than building, it also could provide greater profits. In the early days Walter couldn’t cash in on this profit himself. It was a tightrope situation.

Walter was financing 95 percent of the homes he sold, and on one side of his ledger the piles of four- and six-year mortgages were mounting up; but on the other side were higher piles of currently due bills for materials and labor. Walter would go out and hustle these mortgages to friends, relatives and anyone else he could find who wanted the income. Try as he might, Walter could not find any banks to loan him money against the notes on the houses. In 1955, desperate to end this situation, Jim Walter Homes had formed Mid-State Investment Corp. to do its own financing. Then, to get the permanent capital needed to get big credit from the banks, the company incorporated itself as the Jim Walter Corporation and went public.

The public offering netted the infant Jim Walter Corporation $ 1.2 million and paved the way for the growth from a local success story to a national force in homebuilding and later in building materials. Thirty new offices were opened in 1956 and 1957, and sales increased 185 percent and 171 percent respectively; profits increased even more. But the picture was still not unclouded, and expansion meant more money was needed to finance more sales. As Walter said later, “We had gotten off a small treadmill and onto a big one.”

Finally, in 1956, Walter landed the big money he needed, a $1 million line of credit from Walter E. Heller & Co. (Heller later called Walter “one of this country’s most remarkable young businessmen” and elected him as a director of Heller & Co. in 1961. Today Walter is also a director of General Telephone and Electronics Corporation; Beijerinvest AB, of Sweden; Crown Industries, Inc.; Walter Realty Investors and National Life of Florida Corporation. Mr. and Mrs. Jim Walter both drive Rolls Royce automobiles, and Walter is fond of hunting on his 1,800-acre ranch. He also owns an 81-foot yacht named TICA, which stands for “This I Can’t Afford,” though he no doubt can since he draws a salary of close to a half million dollars each year and owns Jim Walter Corporation stock and other holdings worth more than $25 million.)

Heller was at first skeptical about Walter’s portfolio of mortgages, but after sending a team of investigators South to check out the company, he liked what he saw. For one thing, Walter was strict with people like C. L. Stephens who owed him money. He still is.

When customers get 10 days behind, the first late notice is on its way. A month later, if the account is still behind, repossession proceedings start.

The Mid-State notes were relatively short-term and very profitable because they are computed with “add-on” interest in which the buyer pays interest on the principal, not a declining balance. Thus in 1962, for example, the stated six percent rate was actually close to 12 percent in simple interest. The shorter the term, the greater the lender’s effective yield. Jim Walter’s deceptively low-cost loans actually cost his buyers more than a conventional mortgage would have.

Ironically, at the time when the rest of the housing economy is going to hell courtesy of the Federal Reserve Board’s allowing mortgage money to soar around in the financial clouds at 12 and 13 percent, Jim Walter’s financing is finally becoming competitive.

Jim Walter’s financing rate today is 10 percent, down from 11.4 percent two years ago when Walter was facing usury actions in several states.

But a Georgia banker let out a whistle when he rolled the clock back to compare Walter’s short-term rates to the lower interest rates which prevailed for conventional loans up until a few years ago. “At that time,” he said, referring to the period when thousands of Jim Walter customers bought houses at relatively short-term add-on rates, “it was outrageous.”

Kendall Baker, a Jim Walter CPA, says he feels that the interest payback on a Mid-State mortgage is about the same proportionately as on any other house purchase. “You usually pay about as much for the interest on any house you buy as you do for the house itself,” he says. “It usually works out to about 51 or 52 percent of the selling price. The federals are charging more than we are,”

Jim Goes to Market

Gradually, as the mortgage portfolio increased, finance charges contributed an ever-increasing share of Jim Walter revenues. This money, when coupled with the prime-rate credit Walter was able to receive from major banks by the ’60s, allowed Walter to expand and put his company on a solid financial footing. He began in 1962 by purchasing 34 percent of Celotex, a building materials company. By 1964 he had gained complete control and merged the company into Jim Walter Corporation.

Celotex also brought with it interests in Shore Oil and Development Co., which explores for oil and gas on the Gulf Coast, and South Coast Corp., a Louisiana producer of sugar cane. The fiber left over when juice is pressed from the cane is called bagasse, and this was supplied to Celotex for use in making fiberboard. (The sugar operations were sold in 1979 for $45 million to Mid-South Mortgage Co., though Walter retained the mineral rights.) In addition to fiberboard, Celotex makes roofing, insulation, gypsum wallboard, acoustical ceilings, hardboard and vinyl siding products. In 1967, Walter corraled another piece of the building materials industry by acquiring the Barrett Division of Allied Chemical, a major manufacturer of asphalt roofing and fiberboard. In 1972, Jim Walter Corp. bought the Panacon Corp., which among other things makes asphalt and tar roofing products.

The acquisition of Celotex, Barrett and Panacon made Jim Walter Corp. an integrated company, but the majority of the products of Walter’s building material subsidiaries are sold to other companies. The banking and savings and loan operations also do business only outside the corporation. When Walter sells a house, the lumber is bought and shipped from one of several suppliers in the immediate area where the home is to be built. Though Jim Walter makes many of the finishings of a house, the supplies — for example, doors — are bought from local building supply companies. Explains Bill Davis of the Jonesboro, Georgia, sales office: “We have over a hundred sales offices around the country and the cost of stocking all the styles we would need is just too great. We go out to West [Building Supply] and buy the doors. You could buy them as cheap as we do.”

Bob Michael, vice-president for homebuilding, adds, “I like to go out to a home we’re building and see Celotex dry wall, but we don’t require it of the subcontractors. The only thing we require is that they get the best price. Availability has a lot to do with it. We encourage them to use Jim Walter products when they can but it’s up to them.”

Walter’s line of building materials for residential, nonresidential and remodeling markets is now the largest offered by a single company in the United States. Though the Celotex and Barrett acquisitions marked Walter’s transition from builder to conglomerate, it was his 1969 takeover of U.S. Pipe and Foundry that today seems to be his most significant purchase. Among U.S. Pipe’s extensive holdings were 160 million tons of coal reserves in north Alabama’s Blue Creek field. At 1969 prices, this coal was considered too deep — some of it almost a half-mile beneath the surface — to produce at a profit, but Walter knew this would be changing. Within a year he had decided to develop the four deepest coal mines in North America. This decision meant the beginning of a 12-year, $350 million net investment that currently represents most of Jim Walter Corporation’s capital expansion.

Jim Walter Resources is a new division created after this 1969 acquisition to develop and run the coal mining operations. The mines themselves are located in east Tuscaloosa and west Jefferson counties in Alabama, roughly north of the interstate highway connecting Birmingham and Tuscaloosa.

Into this established mining area, Jim Walter marched with the same confidence with which he had dominated the shell homes industry and had taken control of his share of the building materials industry. Walter’s coal mines in Alabama were producing less than one million tons per year when he took over. By the mid-1980s, if current projections hold, the output will be more than eight million tons per year. His investment to achieve this production is staggering, because most of his coal will be mined with the capital-intensive longwall techniques which are widely used in Europe but unheard of in the South.

Even discounting the tremendous potential of the coal reserves, U.S. Pipe was destined to fit right into the Jim Walter corporate family. It enabled Walter to build a Pipe Products Group which manufactures cast-iron pressure pipe, concrete pipe, pre-stressed beams and numerous other water- and waste-carrying products.

In all, Walter has obtained more than 25 firms since he began to diversify in 1962. He has become the kudzu of the building materials industry, drawing on several occasions the ire of the Federal Trade Commission (more on that later). The four most substantial acquisitions — Celotex, Panacon, the Barrett Division and U.S. Pipe — account for about 80 percent of the earnings of all companies bought since 1962. The various companies work together like a textbook description of diversification. If the housing division’s profits, for example, are low in 1980, the profits from the now-increasing coal production of Jim Walter Resources will take up that slack. No wonder Jim Walter smiles in the omnipresent huge photos in his sales offices.

Jim Goes to Court

Walter likes to have things done the way he wants when he wants; by and large he succeeds. He and his companies have a cat-like aptitude for landing on their feet, and they have needed the ability more and more frequently as they have gotten larger. At the moment, Jim Walter Corp. and its subsidiaries are involved in a string of lawsuits and anti-trust actions, some of them dating from the early 1970s.

Its 1973 coal contracts landed Jim Walter Resources in court when the company did not deliver as much coal to Alabama Power as it had agreed to, due to production delays and coal sales from its Blue Creek Number Three Mine to other customers. Alabama Power sued, claiming it should get all the coal mined from Blue Creek Number Three, or that Walter should pay the difference between the contract price and the purchase price for coal of similar quality from other suppliers.

In all, the lawsuits totaled $576 million. The cases were settled out of court early in 1979. Not only did Jim Walter Resources escape the payment of any damages, but it ended up with an increase in the base price for the coal and a provision whereby some costs for mine safety could be passed on to the utility. All Walter had to do was agree to increase capital outlays for mine development and sell Alabama Power some of the coal from Blue Creek Number Seven, subject to approval from the Japanese steel companies.

Another litigation sore point involved Celotex. Walter explained the acquisition of Barrett to bolster Celotex’s growing business by saying, “We were too big to sit with the boys but not big enough to sit with the men.” He was not merely whistling Dixie in his implication that the merger would make the Jim Walter Corporation powerful in the building materials field. In 1973 a Pittsburgh grand jury indicted Celotex and five other companies for conspiring to violate the anti-trust laws in the sale of gypsum products. Celotex was convicted, appealed, won a new trial, and the case is still pending. In 1974, the Federal Trade Commission ordered the Jim Walter Corp. to divest itself of a big piece of the Panacon Corp., saying the company had become too dominant in the roofing materials business and that the 1972 purchase of Panacon violated the Clayton Act. Walter’s Celotex and Carey-Canadian subsidiaries both manufacture roofing products. Walter appealed, but the original order was upheld by the FTC in 1978, and the divestiture order was expanded to include Panacon’s very profitable Canadian asbestos mining subsubsidiary, in addition to all assets used to produce asphalt and tar roofing products. This decision has been appealed by Walter to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. In April of 1979, Jim Walter Papers, Inc., was fined in federal court in Florida for conspiracy to violate the anti-trust laws in the sale of paper products in Fort Lauderdale and other parts of Florida.

Jim Gets the Blues in Kentucky

Up in the hills of eastern Kentucky, a number of consumers, aided by the Kentucky attorney general’s office, took the Jim Walter Corp. to court on a matter that had nothing to do with anti-trust but had everything to do with the product which made Jim Walter famous: his shell houses. In all, 900 houses were involved, all built by Walter between 1972 and April of 1978. Walter had built 2,100 houses in Kentucky in that period, according to assistant attorney general Ruth Baxter, and the owners of 900 of them believed their homes had some type of construction defect or had been built with low-quality materials. In February of 1978, the attorney general’s office filed suit against Jim Walter, charging that the company had not built homes in a workmanlike way and had misrepresented to the consumer the way the houses would be built.

Within two months, Walter had agreed to an out-of-court settlement under which Walter agreed to pay for inspecting all of the homes involved in the suit and for correcting all construction flaws in Walter homes built in Kentucky between June 16, 1972, when the state’s Consumer Protection Act took effect, and the date of the lawsuit.

“A big part of the problem is that Jim Walter’s original contracts required the customer to accept the responsibility for selecting, maintaining and repairing the site. Most of our problems were in eastern Kentucky in the coalfields. Often the foundation was the problem. There would be cases where the water had seeped in under the foundation and caused the footings to sink. Water off the hills. There is very little land in these parts of Kentucky that has not been stripped for coal, and often what you will have is an acre here or there, usually on the side of a hill. Some of these houses are literally built hanging on the edge of a mountain,” says Baxter.

One of the buyers of a Jim Walter house in Kentucky is Willis Rosson of Fern Creek. Rosson is a mechanic, retired from South Central Bell. In 1975 he paid Jim Walter Homes $9,500 to build on his property an “Islander,” one of the Walter designs which many people build on recreational property. But Rosson picked out the “Islander” for his retirement home. He paid the $9,500 for construction of a shell on a half-basement foundation he had prepared for $2,600. Rosson now has his $9,500 back, and he also got to keep the shell which Walter erected. But Rosson is still bitter and disgusted.

“They subcontracted it. From the day they started it they was not putting it up right. The guy from Jim Walters was out there. They just went on building. It was totally unacceptable, any way you look at it,” Rosson says. “There was good material there. They could have done it right. The subcontractor hauled material away from there every day. He substituted these 49-cent two-by-fours for good wood and then turned around and put the sorry stuff in the house. Everything was wrong with it. The house was pulling apart. The roof leaked terrible for three years. I was hot.”

Rosson said no amount of complaining, either to the subcontractor or to the Jim Walter supervisor, did any good. Finally, he said, the attorney general’s office got involved and ultimately filed the lawsuit which brought him relief. A further part of the lawsuit accused Walter of charging 11.4 percent interest on mortgages for homes costing less than $15,000, a full three percent above the interest limits imposed on such homes by Kentucky finance laws.

The usury charges were still pending against Walter at the end of 1979, but the company moved swiftly to settle the remainder of the lawsuit after it was filed. The court forced Walter to pay Kentucky $25,000 to hire a building inspector solely to inspect Walter-built homes. Assistant attorney general Baxter said that of the 856 homes found to have legitimate complaints, 776 had been inspected by the joint Walter-state inspecting team by the end of 1979. Cash settlements ranging from $50 to $11,000 had been made to 340 of the owners. Additionally, Walter agreed to issue 10-year construction warranties for all homes built in Kentucky after the State Consumer Protection Act took effect. Walter also agreed to inspect building sites before the company erects a home and to inform the buyer of surface or soil conditions which might affect the house after construction.

“Frankly,” says homes division vice president Bob Michael, “I think we learned something in the Kentucky situation. We’ve put in a lot of guidelines since and we have improved our building standard over what it was years ago. Every report that comes in here still isn’t perfect — I’ve never seen a perfect house. But we do have people in each region inspecting every house that is built. We will fix our problems when they come up.”

Willis Rosson says, “I’ve been put to a hell of a lot of trouble over four years. I wouldn’t recommend that anybody have anything to do with em.”

And Jim Walter Homes has some other “problems” coming up which may dwarf those with Willis Rosson and his East Kentucky neighbors. In August, 1979, Jim Walter Homes was one of several homebuilders placed under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission for allegedly shoddy construction practices. The FTC’s Dallas regional office has subpoenaed records for thousands of Jim Walter Homes built over a 10-year period. Walter’s Washington lawyers moved to quash or alter the subpoena, which it called unnecessarily burdensome. Officials at the Dallas FTC office won’t comment on the investigation (nor will Walter officials), saying that it is “not public” at this time. But it is known that the FTC has received an unusually large number of complaints about Jim Walter Homes. Customers’ grievances echoed the Kentucky case, complaining of unfair and deceptive practices, poor workmanship and structural defects.

Setting the Pace

What does it all mean when a truck driver parlays an $895 shell house into a $2 billion conglomerate? And what does it imply for the building industry when this truck driver puts together a system which makes him one of the nation’s largest homebuilders, turning out identical houses the way Detroit turns out cars?

Like the steelmaker who also manufactures nails, Jim Walter is a dual distributor (several times over), producing both materials and finished product. Walter and the other manufacturers of insulation, gypsum board, roofing and other products have the power to drive up the cost of all housing by manipulating material supplies and prices. That leverage in pricing and supply helps secure Walter’s homebuilding niche — at whatever level the company chooses, from “low-cost” to “conventionally” priced.

But Jim Walter’s impact extends far deeper than the marketplace. The company controls land and natural resources extracted from the land as well as the materials made from those resources. It also has the means to build, distribute and finance homes. Walter is the first modern homebuilding conglomerate that started its empire by building houses; it and a few fellow multi-companies possess the ability to make profound, permanent changes in residential construction from landholding to the loan officer’s desk.

Thus far the benefits of Walter’s uniquely broad diversification accrue to the company’s ledger rather than its customers. A piece of Thermax sheathing or three-tab Celotex shingles in a Jim Walter home cost the customer no less than they would in a conventional home built by another contractor. And Jim Walter’s “bargain” homes no longer deserve the name. Walter’s Greenbriar vacation home costs $29 per foot, 90 percent complete — at least as much as many conventional homes.

The company shouldn’t be made a scapegoat for all the ills besetting the industry in the South today, yet it is still unsettling to realize that the very virtue Walter once promoted, that of giving the “little man” some control of the roof over his head, is now often mired in the same hugeness which frustrates consumers and hogties the would-be innovative entrepreneurs of the 1980s. As Willis Rosson once said, “One of the things I run up against most when I was having my trouble, how was I, a retired mechanic, supposed to do anything with a multi-million dollar company?” Not even Jim Walter knows the answer to that one.

Tags

Randall Williams

Randall Williams is a fugitive staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies. He is currently living and working in north Georgia, where he is guiding the start-up of two weekly newspapers, the Chickamauga Journal and the Lafayette Gazette. (1980)

Randall Williams is an Alabama native, a journalist and former editor of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s newsletter. He is now on the staff of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1978)

Hilda Dent

Hilda Dent is a graduate of Sweet Briar College and recently earned an MBA at Auburn University in Montgomery, Alabama. She now lives in Atlanta. (1980)