Being Southern Baptist on the Northern Fringe

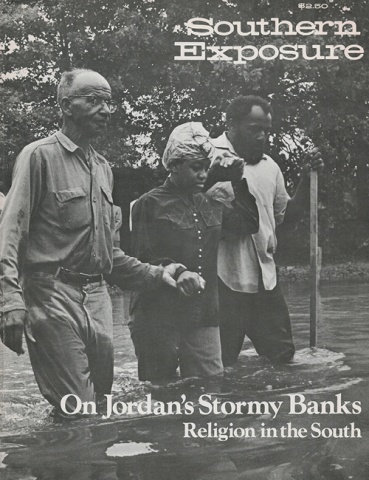

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

There is a time of late afternoon that is special for me, a time when all things fall together. Lines collapse. The edges of objects fade into each other. Smells and sounds mingle together. It is often a time for nostalgia though certainly not of the cheap, destructive sort. It is a time when memory chains are set off by something random and things follow one another in the logic of soft but accurate arguments. It is an important time for me, one when I reassure myself that things are good, that the children will be home soon or are enjoying their play a few houses down the street, that the people around me are not malicious, but are working out their lives in special and kindly ways even when they are, like me, confused.

Lately, I find myself whistling old hymn tunes during this time; not in a self-conscious, show-offy way, as I sometimes do when flaunting my Southern differences before slightly patronizing “general American” audiences. Rather I have found the tunes to be meaningful and real, powerful additions making the time itself still more important. These are the same tunes that are “folk songs” to a younger generation whose experiences have been limited in ways different from mine. They hum and sway as their favorite singers render "Showers of Blessing” and “What A Friend We Have In Jesus” and “Throw Out The Lifeline,” believing that the tunes and words emerged from the depths of a cultural unconscious. They know nothing of such old friends as P. P. Bliss, Fanny J. Crosby, or B. B. McKinney, the people who wrote songs out of need and conviction.

When you know something by heart, you know it so well that it sings itself, without thought or examination. I often sing verse after verse of the old songs in this manner without a hymn book. And though my memory is now poor from disuse, there was a time when I could easily list the books of the Bible in order and recite lengthy passages of scripture. I could locate, on command, any verse of scripture in a matter of seconds in an exercise known as the Sword Drill (“...the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God.” Ephesians 6:1 7).

Accepted doctrine, approved dogma, and supportive apologetics were abundant, surrounding and comforting. They were couched in the highly structured ritual of informality that defines behavior in Southern Baptist life. The four Sunday services, two study and two worship; the Wednesday night “prayer meetings” consisting mostly of brief devotional talks; the Daily Bible Reading program which plotted the course of shared study and assured everyone of reading the Bible through every five years. All these things made it easily possible to know the proper words “by heart” without having to think much about their meaning or their application to daily life, which Äs not to say that they were not applied. Because almost everyone knew the same doctrines, the same words, the same rituals and hymns, “proper” behavior could be carried out in familiar and relaxing contexts, rarely questioned, seldom changed.

Such a system functions well and protects the people within it as long as it is not critically questioned. But like many other young people, I was unwilling to take it without question; my questions led to anger and I left.

There is another meaning to knowing something “by heart,” a meaning that might be phrased more accurately as knowing “with the heart,” for it speaks to the process by which we know something deeply and surely, know it as right in a sense that transcends cultural and social rightness. I have begun to go to church again on Wednesday nights. In my present congregation, we do not call it “prayer meeting,” though it would not bother me if we did. We speak of it as our “family night,” and that, too, is a good name. A small group of young families attends, but most of the people are older. I look out at them some evenings, a sea of gray heads, some of them feeble, some twinkling, some in roisterous laughter, and see that they really are part of my family. I am glad that I can share this night with them and that my children can sense the importance of being here. I want to be a part of this group.

One of the things I want to share is the fact, the knowledge, that they have had great troubles and trials and peace and joy, and that they now know (if they have not always known) a great, powerful portion of their lives “by heart.” I am knowing it , too, as best I can. I’ve made my way back to the Southern Baptist Church, a journey I once thought I could never make in good conscience. Strangely enough, I’ve about decided it is the only way I could come back, that it offers me a path that demands good hard thought and work and “heart” tasks, and is worth the effort.

I

That I, or anyone like me, should return to the church is really not difficult to understand. You do not easily root out of your life a set of behaviors that has filled as many hours, consumed energy on such a scale, and roused emotions to the degree that religion has for me. I cannot remember not going to church. I was accompanied there by my parents who were quite active in it on all levels. Later, it was the place where I met most of my friends and where activities were planned for us that covered the spectrum of our social activity and taught us proper social behavor.

The church provided a huge portion of my education that went far beyond religion in the narrow sense and into ancient history, politics, ethics and even sociology. I have always been convinced, too, that my ease in dealing with imaginative literature stems from daily reading of the King James version of the Bible. I have been directly involved in the processes of literary interpretation since the age of six. That words have deeper meaning, that groups of words lead to unusual conclusions is a mystery to many of my students, but never to me. When the lawyer asked Jesus, “Who is my neighbor?” and He replied with a parable, that was only the first step. In lesson after lesson, sermon upon sermon, that parable was interpreted, applied, explicated and examined for me and by me.

Beyond this extended intellectual activity, the church educated me in matters of sex, social custom, parental relationships, attitudes toward civil authority and countless other areas. Sometimes the answers were swift, abrupt, and explicit: “Don’t Do It.” In other cases, there was a fearful sort of ambiguity: “Every Date Is A Potential Mate.” “Love Your Neighbor” was especially tricky because of racial questions. A similar difficulty could be wandered into by taking too literally the text that “Man looketh on the outward appearance, while the Lord looketh upon the heart.” In spite of this, we always dressed up for church.

It is essential to understand that this teaching was not catechistic. There was no list of rules to memorize and recite other than the Ten Commandments and their New Testament versions. There were no classes in which we formally demonstrated mastery in a specific body of manmade rules or interpretations that were agreed upon in council. Rather we were instructed to turn to the Bible as our single source for proper action and were admonished to behave as Jesus would behave in a similar circumstance. Our image of Jesus, if not austere and remote, was surely properly Southern Baptist.

The suggestion that one look to the Bible for practical instruction is not, I think, a bad one. It is a rich, tough book. The difficulty arises in the knotty area of interpretation. While admitting that the Bible states that women are not supposed to cut their hair, or men to trim their beards, or groups to use musical instruments in church, Baptists have ways out of such problems. Other groups have ways in and out of their own doctrinal mazes, and, as everyone knows, Protestantism is a giant maze of mazes that leads easily into controversy and rancor. Differing interpretations could cause problems if it were not for the fact that almost everyone in the deep South is Baptist.

As a result, Baptists define the cultural norms. It would, of course, be inaccurate to identify Southern Baptist belief and behavior with Southernness. I do not think, however, that it is too far off the mark to say that Baptists are at the very center of the culture. It is with that realization that many of us have broken in anger our ties with this powerful, enveloping, life-consuming institution, for such an identification makes it impossible for the church to call out the major weaknesses, the sins, of the culture.

Often the break has come because of racism. For many years the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), like the ballast in a ship, has steadied the course of Southern racism, sometimes with specific doctrinal “evidence” of racial distinctions but more often by perpetuating and making comfortable the dominant values. Those few individuals and congregations who have chosen to oppose racism as their Christian duty have often been condemned and ostracized for their views. They became theologically suspect and were labelled “liberal,” that basic slur which shifts easily from socio-political to theological application.

The church’s stand on racism is part of a larger opinion that sees “social” issues as beyond the appropriate realm of a religious group. Intent on the cultivation of personal salvation as expressed in the moment of individual conversion, much Baptist doctrine is meant to protect the church from the impurity of social gospel issues. Selective application of the doctrine, however, permits large numbers of ministers to descend on state capitols to lobby against liberalized liquor laws. By contrast, to condemn the Viet Nam war would have been wildly out of bounds, for it would have countered the cultural context in which the church has its being.

Others have broken with the church because of its emotionalism. Its emphasis on individual commitment is used to justify highly charged manipulative techniques. The old traditions of revivalism, exhortative preaching, browbeating and guilt-tripping are all too often brought to bear on the very young. Church rolls are filled with small children because it is quite clear to them that they are expected to make their commitments between the ages of six and twelve.

I, for example, was seven or eight years old when I made my “public profession of faith.” I walked down the aisle during a Sunday night service, quite sure that God had told me to do so. (Indeed, I’m still pretty sure that’s what happened. At least it was not overly premeditated and was the result of a deep emotional response on my part.) When I took the outstretched hand of our pastor, who was a good friend, he asked me if I felt that Jesus had forgiven me for all my sins. Now that’s a strange question for an eight year old, even when he knows the answer. I knew that I was supposed to say “yes,” though I doubt that my sense of sin was up to the standards of that particular preacher. He once found me playing ball with his son in the sanctuary of our church, took the ball from us and said that it would have to be burned. We felt bad about the whole thing, but what it really indicates is that the Southern Baptist line emphasizing the necessity of a child-like faith is not the same as being an adult and choosing a child-like faith. The latter is an act that demands great intellectual and theological sophistication.

Closely allied to this criticism is the view that the SBC is generally anti-intellectual, that it denies much that we know about Biblical history, about the nature of Biblical texts, and so on. But it is not merely in the realm of scholarship that the intellect is missing. Probing sermons, especially those read from notes, are suspect, and heaven help the minister who expresses his own doubts. Too often, emotionalism becomes a disturbing substitute for the kind of deeper exploration which might actually lead to deeper Christian growth.

A third allied criticism is that the Baptist Church lacks proper respect for the aesthetic qualities of worship. Gatherings are generally informal and the buzz of friendly conversation preceding the church service annoys those who wish for a quieter, more respectful atmosphere. The old hymns with their reliance on the imagery of crucifixion have come to be known as the “slaughter-house hymns,” and the more sensitive worshippers object to being asked whether or not they have been “washed in the blood of the lamb.”

Underlying these critical observations is a more nagging concern for the overarching pride and self-righteousness of the whole enterprise. There is, in the Convention, little sense of penitence. Indeed, the answer goes, why should there be. Southern Baptists have been, as they would say, richly blessed. Their numbers continue to grow. Their programs flourish and move to new regions. As individuals, they are among the more prominent citizens in their communities, and they share common roots with their cousins in the farms and pasturelands of the South. The Lord has allowed them to prosper, to create a system of wealth and religious power that continues to be internally defined and that has changed little in over a hundred years.

This pride, it seems to the critic, is sinful. So the critic, especially the young one, becomes the rebel and then the outcast. The critic leaves the church and with it a great portion of his or her personal history. A gap is left in the mind. It may be replaced with political fervor for social justice, with the intellectualism that was found to be missing, with an aesthetic religious experience in a “more formal” church, with an easy humanism, or with a fervent plunge into the cults of humanistic psychology. But it cannot remain empty. Too much psychic stress pulls at the edges. In some cases, like my own, it is filled with a journey back, with an exploration of what it has meant to be Baptist at other times and places, with a reinterpretation of the old symbols. In my experience the journey back does not mean an end to criticism. If anything it means a far more vigilant attempt to make the system responsible. On arrival in the old territory I find there is much worth preserving and a potential for exceptional strength in a time of cultural flabbiness. It is not at all difficult for me to identify myself now as a Southern Baptist, but it still requires explanation.

II

The explanation must begin with the particular congregation of which I am now a part. Any Southern Baptist will certainly understand the importance of that observation, and for non-Southern Baptists it provides the best beginning for explanation. Formally, doctrinally, there is no ecclesiastical hierarchy in the Southern Baptist Convention. No one, no agency, no group, no administrator can tell an individual Southern Baptist church what to do. In practice, of course, there is not a great deal of difference among churches. They look the same, and if asked to define their beliefs, they will sound much the same. It is important for them to affirm liberty while strongly insisting that one can’t believe “just anything” and still be Southern Baptist. Basic doctrines such as the Virgin Birth, the Fatherhood of God, and the fact of the Trinity are accepted easily while exploration of the highly complex nature of such doctrines is not encouraged.

Moreover, the Southern Baptist Convention, the democratic political governing organization, wields a great deal of power and influence in the life of every affiliated congregation. Meeting annually as a group of messengers from each congregation, upwards of 12,000 individuals take care of the issues for the rest of the millions of individuals at home. Most believe that the Convention is the best way to do business. Though there are continual minor controversies over shades of liberalism and conservatism, most individual members favor the maintainance of conservative positions and are quick to criticize the more liberal agencies such as the Christian Life Commission which is charged with comment and education in the realm of social ministries.

Paradoxically, all this voting and dividing and governing has great influence in the life of the individual congregation, and no influence. The money contributed at home is spent by boards whose actions gain their final approval at Convention meetings. The Convention passes resolutions on every issue from abortion to homosexuality to votes of thanks to the host city. Yet any individual can say “this is not what I believe about abortion or homosexuality and besides I think that Norfolk was a lousy place to have the meeting.” The problem, obviously, is that the individual’s voice, ultimately, has little to do with the “big image” of the Southern Baptist Convention. Nevertheless it has a great deal to do with the home congregation, which is also run as a participatory democracy.

A good example of this local autonomy is my own church. Much has been said about the lack of aesthetic sophistication in Southern Baptist Churches, the missing ritual that serves to focus our devotions, tune our minds and direct appropriate actions. Yet, our preacher wears a pulpit robe, an act that would be unacceptable in many churches. An acolyte, also robed, lights candles before each service in our church sanctuary. The choir processes formally into the church, through the congregation and into the choir loft. They sing complex music, the classics of the church, ancient and contemporary. In keeping with their excellence, paid soloists head each choir section, a practice directly counter to the Baptist tradition of volunteerism in such matters. The hymns sung by the congregation are often hymns from the Anglican tradition. The minister preaches with a stated awareness of current theological questions, often referring to contemporary theologians and popular non-sectarian apologists.

In short, to many Southern Baptists we would be too fancy, too formal, too much the up-town church to satisfy their stereotyped version of what it is to be Baptist. It would be assumed, incorrectly, that we are a “cold” church, for that goes handin- hand with the “formal” tag. It might also be assumed, correctly, that the church is wealthy and intellectually oriented. But in no way would these differences enable others to say that we are not Southern Baptists, for this is merely the way in which we choose to worship. We are tolerated by many and praised by some.

Still, the matter of music and clerical robes are surface issues. Perhaps a more indicative example would be the baptism ritual. Baptism by total immersion is one of the most important of the “Baptist distinctives” separating the church from other denominations. Indeed, this image of persons being lowered beneath the surface of water in a baptismal pool or a rural stream is surely the one which non-Baptists, particularly in the deep South, are most conscious of. I was recently asked by a former Tennessee Episcopalian, “Do you still dunk ’em?”

While Southern Baptists do not believe that the ritual of baptism, in this form or any other, contributes one whit to an individual’s salvation, they are convinced that this is the “correct” manner in which the ritual should be observed. It is especially crucial that the symbolism of total immersion death, burial, resurrection—be applied to persons of other traditions who affiliate with Southern Baptist congregations. This implies, of course, that one is not saved until one joins the proper tradition, a translation which most Baptists would feel very uneasy with, but which is under the surface nevertheless.

Many people in my congregation are uncomfortable with this requirement. They say that it is presumptuous, that it is doctrinaire in the worst sense, and that it opens us to the accusation of sinful pride. On a number of occasions there have been moves to change the requirement. Most recently, the church went through a lengthy process of study and self-examination. The minister prepared a series of learned lectures on the history of baptismal rites. Discussion and study continued over a period of a year, turning up some interesting facts. The early church, for example, was guided more by expediency than by doctrine or by the meanings of words. Original languages clearly imply total immersion, yet early churches resorted to pouring or sprinkling when necessary. And so the practice has changed and been changed throughout the history of the church. Even Baptists have been inconsistent in the form of the ritual, and have not always baptized by immersion.

Armed with all this knowledge, all the discussion and prayer on the part of individuals and groups, and all the leadership from men, women and spiritual sources, this congregation, noted for its intellectual image and liberal attitudes, voted. It voted, by narrow margin, to retain the requirement of immersion for all new members, regardless of their previous confession of faith.

There are several points to this example. Most obvious to someone not involved is the fact that the congregation affirmed the more conservative position. That fact is indeed important, for it measures the depth of an attitude toward tradition, toward the distinctive historical factor of being Baptist. It was doubly important for this highly diverse group.

Not so obvious is the importance of considering the issue in the first place. There is some possibility that the congregation, had it relaxed the requirement, would have found itself severed from the fellowship of its local Baptist Association, a group consisting of all local churches affiliated with the SBC. That would have meant little, other than strained personal feelings, for it is quite unlikely that the Southern Baptist Convention would have taken any action on that scale. It has not done so over other issues nor on this one in the few churches that have changed their baptismal requirements. It cannot do so under the strict terms of what Baptists believe because the belief in the autonomy of the local congregation is ultimately stronger than the belief in baptismal form.

Of greatest importance, however, is the fact that the congregation sensed that this discussion was right and that it should proceed. Those members who knew at the beginning that their views would not change realized that for others this was a matter of conscience. Consequently, the discussion, even when heated, was never rancorous. When it was over, there were disappointments, but no bitter recriminations, no betrayed friendships. Persons on opposite sides of the issue had remained faithful to the larger meanings of open discussion and democratic procedures. For those of us who were “defeated,” there was a greater sense of victory, for we were assured that religious liberty had been maintained. No dogmatic, authoritarian rule had been enforced, nor had there been felt any need for separation. We had had our say and could be content with the results. No doubt we would try again later.

III

The congregation was free. I had known it before, had sensed the attitude that made me comfortable. I had heard the sermons that were so different from the ones I had grown up with and felt for the first time that the Southern Baptist church was not somehow inherently restricted from wrestling with the meanings of texts that I had wrestled with privately. I had met individuals who felt as I did regarding social issues. I had learned that here one was expected to express doubt in order to gain strength, rather than hide it in embarrassment and fear of punishment. Still, after the discussion on the baptism question, I knew that I had come home, and that I had discovered something much deeper than I had anticipated. A richer vein existed in this tradition than I had known about.

My journey had been not only a quest for what was valid in the tradition, but also a search for the answers to the theological questions that confront any professing Christian. I had worked out what it meant for me to believe in Jesus in a personal way, and concluded that in His example we have the best record of perfect human freedom defined by an awareness of a transcendent God. Through this example we learn how to accept life and those who live it. We are free to live as we please, so long as we do not harm others, and so long as we work to liberate those who have been and are being harmed and oppressed by evil in the world.

The terrible and vital tension that exists in that sort of free responsibility is the heart of Christianity for me. With that realization, I discovered what I had so feared and rebelled against in the Southern Baptist tradition, and I learned as well what it was in that tradition that I found so necessary, so demanding and so liberating.

The deeply frightening thing about the church for me was its easy acceptance of the culture that surrounded it so that the rules of the culture, so tightly defined and so corrupt in many places, became the rules of the church. Scripture came to be interpreted through eyes of the culture rather than as commentary on that culture. Never did I know the church to rise up in wrath and condemn the culture that fed it. We had defended war and racism and violent confrontation with legal authorities. We had prohibited human development and had crippled with guilt those young people who were trying to discover who they were sexually, intellectually and socially. We were bound rather than free. We were the authorities, the law that Jesus came to fulfill and end. We were the Pharisees, the whitewashed sepulchers. There was deadness about us because we were so closely allied to the world in such insidious ways. Sam S. Hill, Jr., a scholar who has studied the Southern Baptists puts it best.

Potential conflict is aroused by the fact that the Christian church demands a total loyalty, while the South as a cultural system presents itself as a nurturing and teaching agency lacking in seif-critical powers. In very different ways both Christianity and Southernness lay exclusive claim upon the white people of the region.... they are participants in two primary frameworks of meaning, two cultural systems. Their lives are governed by two culture-ethics, God who is society and God who is the subject of existential experience within the Christian community. Both provide context, identity, community, and moral constraint.1

If the discovery of this relationship served to explain some of the death that so many of us had experienced as Southern Baptists, it nevertheless indicated another direction. Once again the faith itself provided the symbol. For deep within the tradition that is entombed in Southern culture, there is the life of belief and meaning, a new life that united Baptist and Christian names in a union of real strength. The discussion and debate on baptism had led us into the heart of what it was to be Baptist. We rediscovered a history and a tradition for ourselves. We spoke again of what it meant to believe profoundly in the ‘‘free church.” We were able to read the words of another Southern Baptist historian with pride.

As a distinct denomination, Baptists first began in seventeenth-century England. Label the religious parties of that period and here is what you come up with: Anglicans (English Episcopalians) are the “conservatives”; Puritans are the “liberals”; Quakers, Congregationaiists, and Baptists are the “radicals”! Think of that! Baptists were not among the conservatives, wanting to maintain the status quo. They were not even among the avant-garde liberals who wanted to tamper with the status quo and change it a little. They were among the radicals who wanted to reverse the religious establishment. That, reader friend, is a heady heritage! One that many Baptists have never learned. Or else it is one they learned and conveniently forgot. Either way, it is a tragic misuse of history.2

This sort of historical realization, and the strength it brings, can lead to a diminution of the pride so often found in Southern Baptist Churches. It is a strength that allows us not only to criticize the denomination itself, but to separate it from the un-Christian aspects of the culture that support it. If the church can stand apart from the culture, then it can get on with the business of calling the world to judgment in the name of the Lord. This task is impossible as long as the world and the church remain identical; but it is essential for Christianity to be truly radical, to cut to the roots of evil, to transform the world with transformed men and women. Christians can speak with authority once again and do so in the best, but often hidden, Baptist tradition.

Perhaps the perspective from the Northern fringe allows me to make this sort of synthesis. We are in a minority here, even in a border state, and things look different. Still, I hope it is not merely an individual matter or even a matter of this particular church. I hear that there are other churches like this one I have discovered and that not all of them are outside the deep South. Perhaps this feeling that we must look more closely at the contradictions that seem so prevalent in our lives is shared by increasing numbers of Southern Baptists. Like ours, they may find themselves embroiled in controversy from time to time. Yet I suspect that one hears little talk of “split” congregations, for there is strength in recognizing free responsibility to one another that is not found in appeals to authoritarian leadership or in easy acceptance of the “old ways.”

Strangely, for me, this discovery of new perspective has had an ironic twist. Now that I can affirm the name and have found a deep worth in being Baptist, I find that I would like to hold on to more of the cultural tradition as well. The identification of culture and theology might not be healthy for theology, but it is probably very good for culture. It legitimizes certain factors and enables them to maintain validity in a time of great shift and change and uncertainty. It anchors experience. The Southern churches, for all their problems, offer individuals, and most importantly, offer families, a center of life. People support one another there. They care about the sick and dying. They love the children of their neighbors in specific ways rather than with a soft concern for the “world.” They grieve when personal problems arise in other homes.

Personally this means that I have, in some ways, become one of the conservatives in my congregation. I constantly remind myself of Brother Will Campbell’s words: “Whenever a church moves out of a brush arbor it loses something.” Translated into my experience, this means that I call for us to spend more time together in church, perhaps even reinstitute the Sunday evening services. I sometimes long for the old hymns during our “high church” worship. I even wish, at times, for a stronger emotional sense in our appeals for personal commitment rather than the carefully controlled sequences in which the sermons are separated from the decisions made by individuals with offering collection and special music. Having suffered from one sort of imbalance — lacking in intellect — I do not wish for any simple reversal that slights or abandons the emotional life of Christian fellowship.

In all of this, I feel old urges rising, urges to call out for change and reform. But when I feel impatient now I know two important things. First, I know that my brothers and sisters here will listen with love and care to the suggestions that I or anyone else wishes to make, though they might not go along with us in the end. There will be no charges of heresy, no denunciations of character. Secondly, I know that my family and friends can look forward to those nights when we go and have dinner with the older people and share thoughts and songs and prayers. We will share our lives. There I find myself part of a community of truly common belief that transcends the forms in which we express ourselves. Being Christian is more important than anything else in my life, certainly more important than being Baptist. But being Baptist makes it possible to be most Christian. It is a personal matter rather than a theological one now. It puts part of my life back into place and fills an empty space that nagged for too many years.

Those evenings of shared experience, the days of controversy and resolution, the peace of worship all contribute new resonances to that quiet time of day. That time has now become a richer metaphor for me. It expresses best what I understand by a scriptural phrase, “the fullness of time.” It is in that time that the Lord chooses to do things in the lives of men and women who can then do things in the world. I am more and more comfortable with that phrase. No less impatient in my need for reform, I have learned to be far more patient with people. I am not alone. Leaving the church, then, is not an alternative. I must simply wait for a while.

1. “The South’s Two Cultures,” in Religion and the Solid South, ed. Hill, et. al. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1972, pp. 46-47.

2. Walter B. Shurden, Not a Silent People. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1972, p. 12.

Tags

Horace Newcomb

Horace Newcomb is a graduate of Mississippi College and the University of Chicago. He teaches American Studies at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and this year is a fellow of the National Humanities Institute at the University of Chicago. He is the author of TV — The Most Popular Art (Doubleday/Anchor) and edited Television The Critical View (Oxford University Press). (1976)