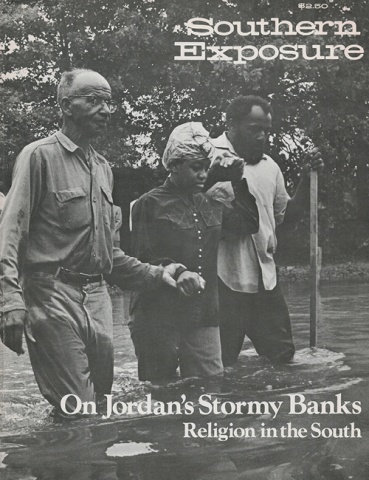

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Trying to describe the religious folk music of the Southern mountains is a little like trying to organize the church itself — songs, like people, just will not line up quietly in neat rows. Still, there are patterns in this varied and vital tradition, and searching for them reveals, as well as anything can, the intensity of religious feeling that has always been part of mountain life.

Religious singing in the mountains flourished with the wave of revivals that has swept the region in the last two hundred years. The emotional intensity of these movements combined with the strong musical traditions of the area to produce some of America's most powerful music. It is true folk music — home-made music that people use in their everyday lives to express their deepest feelings.

At the same time, the familiar dynamics of social mobility have acted as a counterweight to this tradition. Typically, churches which begin on the fringes of established religion change as they get more rooted; a generation that goes to carpeted churches and listens to the choir looks back in embarrassment on its predecessors who shouted and danced on bare boards. This process has happened to every religious revival movement in the mountains. But persistent economic hardship has prevented the mountains as a whole from going through this upwardly mobile change. As a result, the reservoir of folk creativity, often left behind by various churches, has waited for the next round. The process continues today.

Roots

Folk traditions in the British Isles go back unbroken to the pre-Christian era. Their heathen origins, however, meant that English songs were repressed by Anglicans, and even more by the Puritans. Of the little religious folk music that survived, only a small portion crossed the waters with the early settlers. The New Puritans continued to scorn music and celebrations altogether, and finally reduced church singing to no more than two dozen tunes. Only in the backwoods could people who wanted to sing do so unhampered by convention or the restrictions of the church. It was here on the New England frontier, outside the cities where music was controlled by the wealthy, the educated and the church, that folk music took its first root in America.

Singing schools, conducted by itinerant masters and held in taverns, quickly grew up to satisfy people's desire to learn religious music. They taught the notes of the scale by an Elizabethan system of "solmization" in which the seven-note scale is rendered FA-SOL-LA-SOL-LA-MI. Singers could learn tunes by these syllables before singing the words.

Then around 1798, two innovators named Little and Smith found a new way of putting music on paper. They took the four syllables FA-SOL- LA-MI and gave each a separate shape on the musical clef:

Shape-note singing will no doubt rank as America's great contribution to the teaching of music. It simplified the notes and their relationship to each other, allowing the old singing masters to teach music to people who the city-bred musicians considered hopeless. The system quickly won acceptance and its influence continues to the present day, especially in the South.

The music centers in the East were less friendly. They disdained the new works of the self-educated, shape-note song writers, forcing them to develop their own publishing institutions. The new music drew heavily on folk tunes and the democratic spirit of post-Revolution America; the tunes were lively, strong, and popular. Harmony was introduced, making the music all the more unconventional to the Puritan critics. Nevertheless, writing music in shape-notes persisted. Perhaps the best of the little recognized but highly talented shape-note composers was William Billings (1746-1800), a cobbler who, according to the Sacred Harp, “was criticized by many musicians and music writers, and while he did not believe so much in rules, he wrote some very fine music." Another rugged individual, the Reverend John Leland, was described vividly in the Sacred Harp:

In 1808 he took a preaching tour from his home in Massachusetts to Washington with his Cheshire cheese which made his name national on account of that trip... The farmers of Cheshire, of whom he was pastor, conceived the idea of sending the biggest cheese in America to President Jefferson. Mr. Leland offered to go to Washington with an ox-team with it, and preach along the way, which he did. The cheese weighed 1,450 pounds. He died with great hope of rest in the glory world.

Revivals

Despite the established church's distaste for shape-note singing, the music was well developed by the time the Baptists and Methodists began to penetrate the religious vacuum of the frontier. The Presbyterian Church dominated the New World outposts, but it held little appeal for the poorer and less-educated settlers. In sharp contrast to the Calvinists' elitism, the revivalists' Arminian doctrine (salvation open to all by faith) and down-to-earth emotional style struck a responsive chord on the frontier. The democratic impulse that had nourished the rise of religious folk music was now being tapped for an even larger social movement. As one historian writes, “The close connection of the Colonial Government, the Established Church, and the aristocracy of the Tidewater makes it impossible to treat the (revival) movement as solely religious. It was more than that. It was a protest against religious, social and political privilege — and because education was closely associated with the privileged classes, somewhat too against education."1

Revivalists, especially Baptists, were heavily persecuted from 1750 to 1775, but they flourished nonetheless. The influence of their doctrines on the frontier was boundless, and by the dawn of the nineteenth century they had unleashed a storm of religious activity in all but the plantation South.

The revival movement culminated in that amazing phenomenon, the camp meeting — a gathering of hundreds or thousands of people in remote areas for days or weeks of continuous religious observances. It was with the camp meeting that religious folk music took root among the masses of the Southern mountaineers. The first camp meeting was held in Logan County, Kentucky, in 1800. For the next 30 years, common people — mostly black and white farmers — attended these incredibly intense gatherings that centered on the struggle within the participant over her/his feelings of sin and salvation. Preachers vividly described heaven and hell. Songs, prayers, groans and shouts from repentant sinners and the energy released by so many people crowded together made the camp meeting an irresistible force. One observer writes, “at no time was the floor less than half-covered. Some lay quiet, unable to move or speak. Some talked but could not move. Some beat the floor with their heels. Some, shrieking in agony, bounded about like a fish out of water. Many lay down and rolled over for hours at a time. Others rushed wildly about over the stumps and benches, then plunged, shouting 'Lost! Lost!' into the forest."2

The singing at the meeting was nothing less than pure folk music. Baptists and Methodists generally used the hymns written by John and Charles Wesley and Isaac Watts, who set out to write for "the meanest Christians" and therefore used plain English. But on the frontier, people persistently made their own music. Louis Benson, the historian of sacred music, deplored the camp meeting's “illiterate and often vulgar Revival Hymnody":

The people were ignorant, the preachers were itinerant... and the singing largely without books... The tunes had to be very familiar or very contagious, the words given out one or two lines at a time if not already known. Under these conditions the development of...a rude type of popular song, indifferent to anything in the way of authorized hymnody, seems to have been inevitable.3

Benson was accurately, if unwittingly, describing the creation of religious folk music — an evolving body of songs improvised from familiar hymns and the scriptures, interspersed with refrains and set to easily singable tunes.

We know about the camp-meeting songs largely because of the shape-note songbooks, which were firmly established in the South by 1810 and shortly afterwards disappeared everywhere else. Collections were introduced as late as 1855, and several are still in print, notably the Sacred Harp, New Harp of Columbia, and The Southern Harmony. In the years before the Civil War, the books and their accompanying singing schools meant music for large numbers — the same folks, by and large, who went to , camp meetings — so the songbook compilers included many camp meeting songs. From these songbooks we can see the vital process that produced a large body of native folk music.

• Familiar words were set to new tunes. For example, the Sacred Harp has five tunes for "When I can read my titles clear to mansions in the skies," five for "Farewell vain world, I'm going home," and six for

On Jordan's stormy bank I stand

And cast a wistful eye

To Canaan's fair and happy land

Where my possessions lie.

Ballad tunes were used for sacred songs ("Lord Lovel" became "And Am I Born to Die"). So were fiddle tunes, considered "too good to remain in the exclusive employ of the devil." Interestingly, the songbook composers preserved some fiddle melodies in jigtime (6/8) as well as the usual reels (2/4 or 4/4).

• Music was designed to involve many people, not just a few trained specialists. Group singing was more important than a good "performance." In the shape-note books each of the three or four parts is developed like a melody, a practice resulting from what George Pullen Jackson called "southernizing." Southern frontier congregations had no instruments to carry harmony and no choir director to assign parts, so the alto part had to be interesting — or no one would sing it.

This sort of democracy extended to the singing style as well. "Who is going to tell Sister So-and-so not to step on it quite so hard," asked Jackson," and why, in the name of good sense, should she bear the audience in mind when there is none? This is democratic music making. All singers are peers. And the moment selection and exclusion enter, at that moment this singing of, by, and for the people loses its chief characteristic.4

• Complicated texts became more simple and repetitive, thus more suitable for group singing. This additional democratic feature of camp-meeting songs is similar to black spirituals, and in fact, some songs from the period have been preserved among singers of both races. There is some dispute over the direction of this interchange. Jackson pointed out that blacks learned Christianity from whites and probably learned white music also. Folklorist Alan Lomax argues that blacks led in developing "songs of great beauty within the fragmentary compass of the easy-to-sing congregational leader-chorus formula; and it was in this direction that the white folk spiritual has steadily developed."5 Certainly frontier religion brought the two races closer together socially than any other activity in the old South.

The result of this freewheeling cultural crusade was quite astonishing: hundreds of thousands of people, often illiterate, learned to sight-read music and sing in four-part harmony — an achievement of which store-bought music was and is incapable. From this creative ferment evolved many of the forms of mountain religious music we know today, including the familiar verse-chorus form and the spiritual, like "Bright Morning Stars," that is largely chorus.

Retreat

The tide of religious enthusiasm was clearly shifting by the mid-1800s. As early as 1830, trained musicians had settled in Southern cities and driven the uncouth shape-note singers back into the hills. The more urban Methodists and Baptists had never been too sure about the "excesses" of the camp meeting or the perfectionism it implied. As time went on, their disapproval was less and less subtle. The former underdogs were by now well off, well accepted, and well enough satisfied to be uncomfortable with the crudities of the past. They came to look down on the average mountain church — and its music. For example, the first general Methodist hymnal (1859) systematically ignored camp-meeting songs, taking only 17 of its 357 tunes from the shape-note books, and none of those had camp-meeting origins. Only in the mountains were people able to keep up their own music without undue interference from those who thought it unseemly.

In the years following the Civil War, the mountain churches split and split again — evidence not only of doctrinal difference but of a desire to keep the church local, democratic, family- and community-centered. Isolated from each other and from the outside, communities built up individual song traditions. Some churches used instruments, some did not; different ones used different tunes for the same texts. Often enough churches split over whether to adopt some musical innovation, with one faction choosing to "seek the old paths and walk therein." Nevertheless, religious folk music continued to evolve in the mountains, as did fiddle music, old ballads, and the like.

The two traditions that survived the best, that dug deep in the hills and can be found intact today, are shape-note singing and the music of the Old Regular Baptists. Shape-note singing seriously declined after 1870, but its widespread influence continued. Groups using the songbooks still meet in north Alabama, east Tennessee, western North Carolina and north Georgia. More importantly, I believe the experience of so many people singing harmony helped shape a larger tradition of trios and quartets as well as particular features of popular music today. For example, the use in many shape-note songs of a harmony part pitched higher than the melody (completely foreign to conventional church music) still survives in the high harmony heard in so many country churches and bluegrass songs.

The Old Regular Baptist Church preserved a style of singing wholly different from anything else in the mountains. As Calvinist Baptists, their doctrines differed radically from the Arminian revivalists: if salvation is predetermined, revivals are a waste of time. In fact, the church was known for awhile as the "anti-missionary Baptists" (see Ron Short's article elsewhere in this issue). In general, they disapproved of instrumental music and displays of emotion in church, but they shared a number of tunes and texts with the camp-meeting and shape-note singers. The Old Regulars sing now, as they did in the nineteenth century, in complete unison; words are either lined out by a song-leader or read from a songbook printed without music. The tunes are slow, solemn, highly ornamented, and quite often in archaic-sounding modes or gapped scales (five tones instead of seven). Other traditions, including the early Puritans, the camp-meeting revivalists, and even today's Old Order Amish, use the lining-out method, but nothing in American music compares to the power of a group of Old Regular Baptists singing their somber tunes. Even when standard hymn texts are used, they are sung to different music. For example:

The details of other developments in religious folk music immediately following the Civil War are largely lost forever. We know that many congregations refused to change at all. Others clung to the musical forms of the past as they sang new evangelical hymns "in the old manner, with marked and arbitrary rhythm and inserted slurring half notes."® The awareness of the outside world's hostility toward their forms of worship seems to have increased steadily as Emma Bell Miles recalled in her remarkable book Spirit of the Cumberlands (1905):

God knows what the old ceremonies mean to those who take part in them; but such is the persecution in some places where the curiosity of the town is pressing close in on us that even after a congregation has met together to hold a foot-washing, if any city people are present who are not well-known and trusted, the occasion will be quietly turned into an ordinary preaching.

But neither repression nor inaction from the mainline denominations could keep the religious spirit of the lower classes from bursting forth. In 1867, a National Holiness Movement started (the source of the present Church of the Nazarene) and when it assumed respectability, another holiness movement called the Latter Rain Movement began in east Tennessee in 1892 (which led to various branches of the Church of God). Similarly, revival activity on a local level periodically erupted, fell away, and returned.

Re-entry

The next major period for religion in the mountains began around 1900 when the outside world came crashing back in. Appalachia's rich timber stands, then coal, brought in capital and capitalists. Coincidentally, the national denominations discovered in their own back yard a people so benighted that they required the church's best missionary efforts. The outside church continued to pity or scorn the uneducated, undisciplined, emotional mountaineers, but now it wanted to transform their culture, their entire life style, into something more familiar to mainstream American institutions — a process which, of course, helped the economic exploitation of land and labor.

The music the missionaries brought with them included the products of a commercialization of religious music that began after the Civil War and continues to the present. Newly respectable church members wanted a more refined sort of music which would suit their calmer decorum, and a number of writers began to fill this need, notably P. P. Bliss ("Almost Persuaded," "Hold the Fort"). The style turned into a musical movement when a travelling revivalist named Dwight L. Moody hired Chicago YMCA singer Ira D. Sankey. Sankey's moving tenor added a striking emotional appeal to Moody's preaching and soon the pair were enthralling throngs on two continents, making them the first of the "superstar" evangelists. Sankey himself wrote hundreds of songs, now mostly forgotten, and other writers were not long in following. Publishing houses quickly issued songbooks, recognizing that there is more money in peddling copyrighted originals than in folk songs. Homer Rodeheaver (who sang with Billy Sunday) was the most prominent entrepreneur of what has been called a "religious Tin Pan Alley."

This music was essentially a religgious version of Victorian popular music, with flowery tunes (almost always in major keys) and conventional harmonies. Where frontier people had sung of salvation through struggle, the new music talked of salvation through quiet acceptance — an obvious way of encouraging people to reconcile themselves to the emerging industrial society. Optimism was the encouraged mood, and revivals flourished amid thickets of joy bells, heavenly lifeboats and fountains of delight.

There is no record of what happened when this music was introduced to the mountains, but shortly afterwards the mountain gospel song (of the sort recorded by the Carter Family) made popular evangelistic music and the older mountain traditions, taking themes and images from the mainstream music and vigor and directness of tune and style from folk music. Most of the popular tunes are owned by one publisher or another; but "Keep On the Sunny Side," "I'll Fly Away," "Will the Circle Be Unbroken," "Somebody Touched Me" and many similar pieces deserve at this point to be called folk songs.

Needless to say, the folk roots of gospel music are not well cared for, certainly not by the publishers. Few songbooks have more than a token of the old music. Most are harmonized for the pianist's convenience, not the singer's interest. The old minor tunes are largely gone, as are the archaic and beautiful five-toned ones. Songs that country-church singers render (in a more or less oral tradition) with a steady driving beat are often written with a singsong, watered-down rhythm. Publishers have issued songbooks and sponsored singing schools to popularize their music, just as they did a century ago — only now the music has more connection to a safe and sedate mainstream than to folk traditions.

The missionary churches left little room for religious emotion or for social action. It is not surprising then that a reaction burst out in the form of the Pentecostal Holiness movement, which swelled in the 1920s and within two decades had, by one estimate, as many adherents as any other brand of Protestantism. Like the emotional revivals of the past, Pentecostalism appealed to the dispossessed in society, whose ranks were swelled by the Depression. Like the previous revivals, the movement released a vast reservoir of energy and emotion. Once again, people danced, sang, spoke in tongues and in other ways reproduced the climate of the camp meetings, though now in more hostile surroundings. One Methodist historian of sects claimed Pentecostals attracted people with "unstable nervous structures ...the ignorant, in whom the lower brain centers and spinal ganglia are strong." Others have called them apolitical for their rigid doctrinal rejection of the world, but this seems to me to be consistent with a belief that the world as we know it is truly in need of radical change, a belief that has led many country preachers to be excellent organizers for social change.

Like the previous revivals, the Pentecostal movement made full use of the power of music — lively, simple, repetitive, accompanied by guitars, banjos or whatever is handy, and involving the whole group. Alan Lomax notated the following piece from Kentucky, pointing out that it used the very old leader-chorus form of a Negro work song:

Today

At present, religious music in the mountains covers a cultural range equivalent to that of secular music. At one side is the more or less pure folk music of Regular Baptist and Old Harp Singers; on the other the Nashville-style slick gospel groups like the Oak Ridge Quartet, which recently achieved the distinction of being the first gospel act to book into a Las Vegas resort. To get some idea of this territory one has only to turn on the radio Sunday morning. Start early — stations rarely give rural churches prime time — and consider the fact that this is the only time you can ever turn to the media for live folk-style music. Religious music is subject to the same forces as all mountain music, including commercialization, emphasis on polish and performance, and the general invasion of city culture into the country — and as Dr. Jackson said so long ago, "city people do not sing." Still, churches have been able to shelter more handmade mountain music than any other institution. To hear it is to renew and affirm the journey mountain people have traveled in the last 200 years.

Footnotes

1. John C. Campbell, The Southern Highlander and His Homeland (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1969 reprint).

2. Louis F. Benson, The English Hymn, 1915, as quoted in George P. Jackson, White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands (New York: Dover, 1965), p. 215.

3. Ibid.

4. Jackson, White Spirituals.

5. Alan Lomax, Folk Songs of North America (New York: Doubleday, 1960). 6. Campbell, The Southern Highlander.

Tags

Rich Kirby

Rich Kirby lives in Dungannon, Virginia. He has been a student of mountain music since his grandmother sang Old Regular Baptist hymns to him as a boy in Kentucky. These days he sings on records like New Wood and Cotton Mill Blues (June Appal) and plays with anybody who'll stop to pick a while. (1976)