'The vultures are circling': After Helene, N.C. organizers fight for Appalachia's future

A washed-out road after Hurricane Helene in rural Watauga County. (Photo: Chris Kromm)

When Hurricane Helene tore through Southern Appalachia on September 29, unleashing trillions of gallons of water and leaving more than 1 million people without power, it caught many in the mountains by surprise.

“I was off-mountain when everything went haywire,” said Moriah Cox, a native of eastern Tennessee who now lives near Boone, a town of 19,000 in the northwest corner of North Carolina. “I was two and a half hours away from home, watching things coming in on social media, and realizing how bad it was getting. I don’t think any of us knew how bad it was going to potentially be.”

Cox learned that a house across from hers had slid into the river, and was terrified that her own house would flood and her cats would drown. After waiting for a tornado warning to lift, she jumped into her car and started driving into the mountains; she later realized she was driving alongside another tornado, but didn’t stop.

“On the way up, I saw maybe a quarter of the destruction, and started thinking, ‘My God, what about everybody else?'”

Cox and others in the area may have been blindsided by the scale of Helene’s devastation, but she was prepared to take action.

Cox works for Down Home North Carolina, a grassroots group organizing working people in small towns and rural communities across the state. Two years ago, Down Home launched local chapters in Watauga County, where Boone is located, and neighboring Ashe County, and the group’s resources and relationships have been an essential foundation as it sprang into action to provide hurricane relief. As Cox said, “We’re operating off of networks that we’ve been connected to, through people we trust.”

Those connections, and the commitment of local organizers to a “people-centered” storm response, Cox and others say, have not only been key to the success of meeting immediate community needs, but will also be critical as they face the grueling challenges of a multi-year recovery.

‘People are incredibly selfless’

Six days after Hurricane Helene struck western North Carolina, I met Cox and three other young organizers at the Daniel Boone Inn in downtown Boone, where the team had fashioned a bustling emergency response operation.

The night the storm hit, Cox and others in the Down Home network put out a call to meet and plan a response. By the next day, they were creating a “war room” at the Inn, plastered with sticky notes containing updates on how neighbors were doing, listing people’s supply needs, and volunteers ready to help.

Despite a lack of power, internet, or reliable cell phone signals, they managed to draw 45 people the first day, and more than 100 the second. The operation steadily grew over the first week.

“People that had chainsaws and vehicles, we were able to get out there,” said Mikey Bugge, Down Home’s western field organizer who also lives in Boone. “We were sending people to identify roads that we could get to people on, checking people for what their needs are. We’ve been distributing hot meals, supplies, food, water, clothing, cleanup supplies, toiletries, tools ...”

The team, under the name the Highlander Collective — which includes Down Home members as well as other active volunteers — credits their local roots as important to their success in rapidly and effectively delivering aid.

Members of the Highlander Collective, who have been coordinating relief efforts in Watauga County, N.C. Left to right: Mikey Bugge, Nate Coppenbarger, Moriah Cox, and Claire McCoy. (Photo: Chris Kromm)

“You can’t beat the local knowledge of someone who’s been here, who knows where the roads are, because there’s so much that aren’t on maps,” said Nate Coppenbarger, a native of the North Carolina mountains who works at the Inn, and is also a Down Home-endorsed candidate for Watauga Soil and Water Conservation District Supervisor. “There’s something to be said for having driven these roads before, and knowing what to expect around the next bend.”

Before Helene, Down Home teams in Ashe and Watauga counties were organizing residents around issues like affordable housing and mobilizing voters for the upcoming November elections. After the storm, those teams — which included canvassers and volunteers who themselves didn’t have power or water — switched to gathering surveys of people's needs and getting help. As of October 8, Down Home had collected 668 surveys in-person on doorsteps, and 1,416 via text, after sending more than 60,000 messages to their contacts.

“Through the assessment surveys and asking people what their needs are, we’ve been able to get generators to folks, some insulin, medications,” as well as a host of other resources, said Claire McCoy, a student at Appalachian State University in Boone and member of Down Home’s Watauga chapter who’s been helping coordinate supplies. “People are incredibly selfless, and it’s honestly overwhelming.”

‘An apocalyptic scene’

The day after meeting the aid team in Boone, I joined a group of volunteers and Down Home staff driving into the remote country roads of Watauga County to check on residents affected by the storm. Many of the bridges that led to houses or into mountain neighborhoods were wiped out, forcing us to cross a river by foot and hike up the mountainside to reach homes.

Leading our outreach team is Jon Council, a gregarious carpenter and North Carolina native who lives with his wife Peden some 15 miles outside of Boone. It had been a week since Helene stormed through, and their house still didn’t have power or water.

Jon and Peden Council at their home in Watauga County. (Photo: Chris Kromm)

Every day since the storm, Council has been driving and walking around the county, going house to house to see how people are doing and delivering aid in whatever form is needed. He says he’s barely slept since the storm hit.

“We’re out until dark [doing relief visits], and then I have to organize the routes for the next day,” Council said. “It’s an apocalyptic scene.”

After Helene passed, he remembers walking out across the flooded hills near his house — “in my damn sandals, I didn’t even think to change, I just had to see how people were doing” — to check on neighbors. His eyes water as he recalls two friends who are among the more than 230 confirmed dead from the storm.

As we pull up to each house, Council flips through a notepad to review pages of scrawled details about people’s needs, and the team gets to work: checking on food supplies, hauling sections of a tin roof that were blown off, filling up gas in home generators that could be people’s only source of power for weeks, maybe months. A medic on the team tends to those with known health conditions who are cut off from doctors and medications.

A relief team brings food and gas while checking on a home in Watauga County. (Photo: Chris Kromm)

Council got involved working on environmental issues for Down Home N.C., and is now running a grassroots campaign for the Watauga County Commission in this fall’s elections. Many of his campaign signs are hand-made, and his platform — which includes protecting riparian zones that would be buffers between rivers and new developments, and expanding affordable housing — is even more resonant in the wake of the storm. He said he’s stopped campaigning since Helene hit: “If I lose this election because I’m out doing disaster aid, so be it.”

“This is how Appalachians have survived,” Council says of the people-helping-people ethos of the mountain Hurricane response. “We’re tighter than we’ve ever been.”

The housing crunch

While organizers and volunteers have been working non-stop to meet urgent needs, they are also grappling with the mid- and long-term challenges to full recovery — and how they intend to protect this region they call home.

Near the top of the list of concerns is housing. Lack of affordable housing was already a focal point for Down Home N.C. before the storm. A January 2024 report by the N.C. Housing Coalition found that 66% of renters in Watauga County, and 43% in Ashe County, had difficulty affording housing, and Down Home had launched campaigns to increase affordable options and pass rental housing standards in both counties.

“One [rental] complex [in Boone] just got completely destroyed,” said Mikey Bugge. “They immediately condemned it, and they’re just handing people their security deposits and telling them to get out.” Down Home is sending out teams to notify residents of their legal rights. But the larger issue is they have few places to go. “The number of displaced people is one thing,” Bugge adds. “The fact that there’s no available housing stock to put them into just complicates the matter further.”

Those hoping to buy a home have faced equally grim prospects: Driven by demand for second homes, as well as Airbnbs and other short-term rentals, the median sale price of houses in September 2024 had ballooned to $629,500 in Watauga and $407,500 in Ashe, according to Rocket Homes.

And Helene damaged or destroyed hundreds of thousands of homes, exacerbating the housing shortage. As of October 5, state officials reported that at least 23 shelters housing 1,244 people were operating in western North Carolina; many other people have fled to stay with family or friends. Due to the topography and severity of damage, Duke Energy estimates 100,000 customers in the hardest-hit areas will be without power indefinitely. Those trying to stick it out in their homes without reliable power face colder weather, as temperatures this month drop into the 30s at night.

‘The vultures are circling’

After the home visits in Watauga, I drove 45 minutes northeast to Jefferson, a town of some 1,600 people in Ashe County, where Down Home was hosting a community meeting at the Jefferson Odd Fellows Lodge #38.

Community meeting hosted by Down Home North Carolina in Jefferson, N.C. (Photo: Chris Kromm)

Ashe County is more rural and its houses more isolated than in Watauga, making outreach even more difficult. Austin Smith, who manages Down Home’s western regional organizing efforts, said the group was sending out 30 or more canvassers a day to reach people in their homes, deliver supplies, and check on what they need.

At the meeting, residents bemoaned the rampant disinformation about FEMA circulated by right-wing politicians and now percolating into their communities. They also strategized about how best to inform neighbors about applying for FEMA and other assistance, and ensure money gets to those who need it most — one of the best ways to quell rumors and false claims.

“People need to see these [FEMA and government relief efforts] happening,” said Nancy Beth Weaver, an Ashe County native who grew up on a family apple orchard and livestock farm, and another county commission candidate running with Down Home’s support.

The mood grew increasingly angry as attendees swapped stories of receiving unsolicited text messages from developers within days of the storm, asking if they were interested in selling their homes.

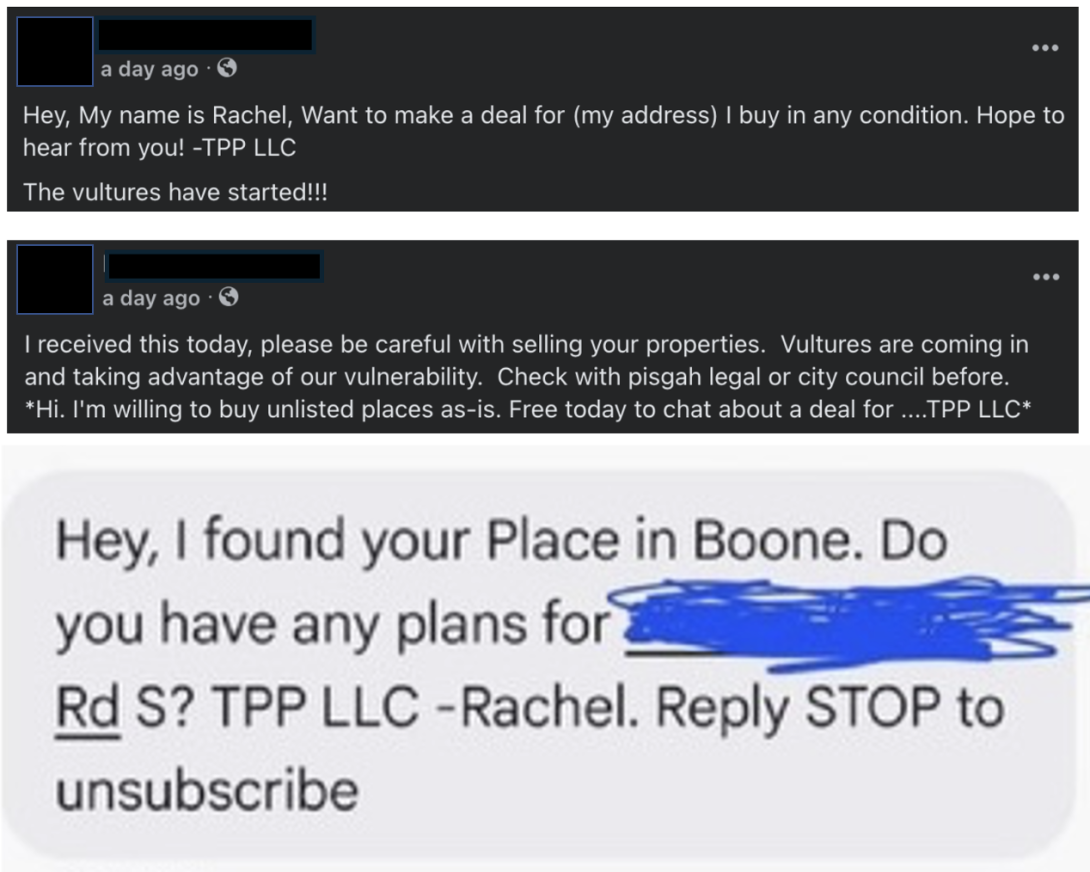

“Hey, My name is Rachel, Want to make a deal for [address redacted]? I buy in any condition. Hope to hear from you!” read one message from real estate company TPP LLC and shared on a local Facebook page. “Hi. I’m willing to buy unlisted places as-is. Free today to chat about a deal for [address] TPP LLC,” read another. Facing South received a copy of a similar text sent from Rachel at TPP LLC to a resident in Boone.

Texts sent by developers and received by residents in western N.C., posted on Facebook (top two images); similar text sent to a resident in Boone and shared with Facing South.

“The vultures are circling,” said a woman next to me at the meeting.

The threat of corporate real estate firms preying on people’s desperation — and profiting from their displacement — was also on the minds of the Boone organizers.

“These outside developers are looking to take advantage of people who have lived somewhere all their life,” Nate Coppenbarger said. “They’re going to be shown more money than they’ve ever seen. They won’t have had power for months. And the money they’ll be offered will be a fraction of what that land is worth.”

Which, those working in Ashe and Watauga counties argue, raises a question important not only to local people at risk of being pushed out of their homes, but tourists from around the country who flock to the region, drawn by their love of mountain culture: What’s Appalachia without Appalachians?

Nancy Weaver in Ashe County believes that, if Down Home and others can rally communities around a common goal — ensuring that all the working people who make up mountain communities can stay and thrive in the wake of disaster — it can help cut through disinformation and political divides. “If they understand that our mission is to protect Appalachia,” she said, “We’re on their team.”

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.