‘Heirs to a powerful inheritance’

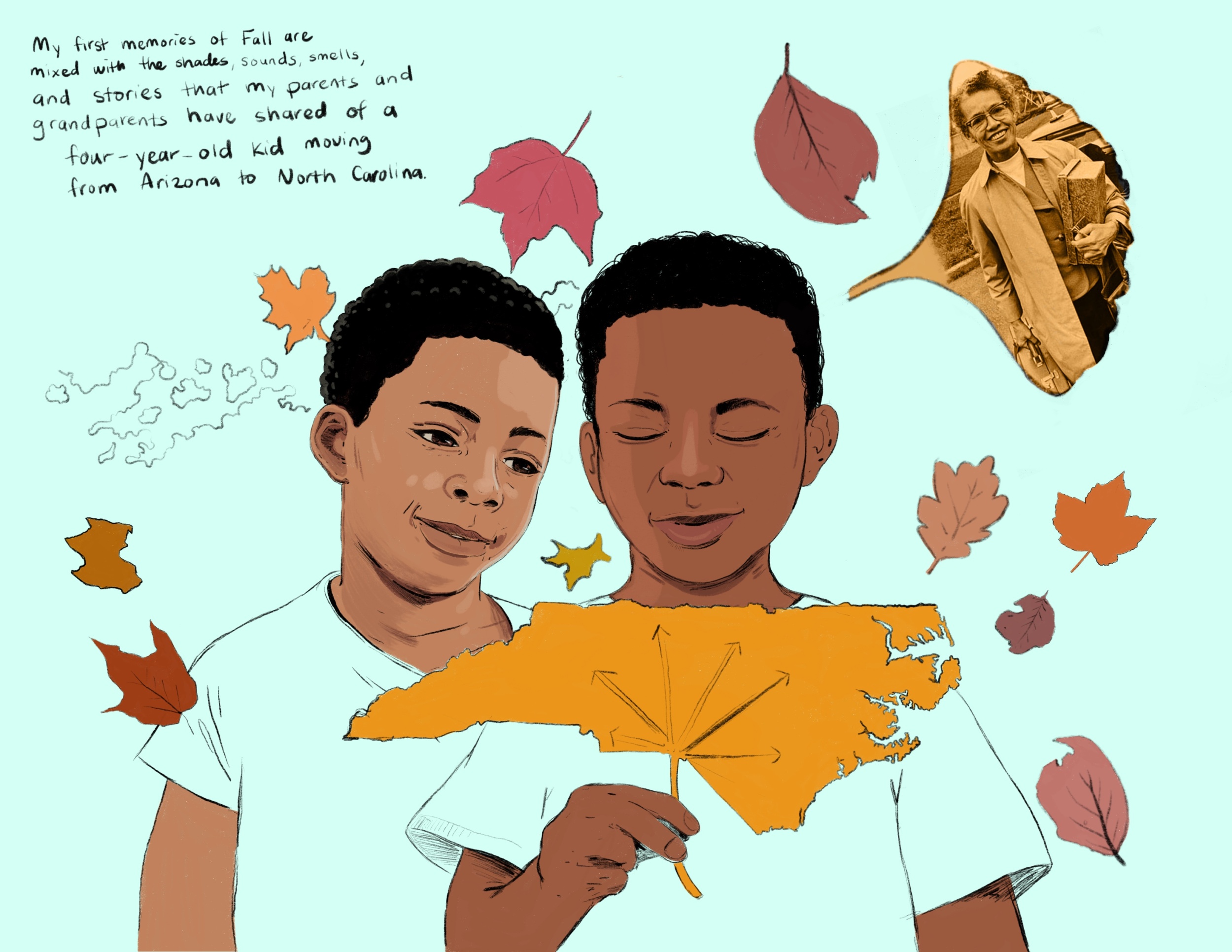

Bryce Cracknell and Trey Walk. (Illustration: Wutang McDougal)

This essay is the third in our CAROLINADAZE series, a joint project with Common Cause North Carolina featuring the voices of young North Carolinians and their visions for a better future for NC and the South.

This essay is the third in our CAROLINADAZE series, a joint project with Common Cause North Carolina featuring the voices of young North Carolinians and their visions for a better future for NC and the South.

The following article contains an anti-Black racial slur.

Bryce

Green turns to yellow, yellow to gold, gold to orange, and orange to red. The sugary, musty aroma of fallen leaves. The air’s soft silence is broken by a rhythmic crunch beneath my feet. With each stride, I step deeper into wonder.

My first memories of fall are mixed with the shades, sounds, smells, and stories that my parents and grandparents shared about a four-year-old kid moving from Arizona to North Carolina. Apparently, as a caramel-colored, curly-headed child, I would stop at every opportunity to pick up and admire the vibrant leaves. Through these childhood encounters, I developed a sense that I was connected — to the natural world, to North Carolina, to the soil. Visceral and divine. A sense of connectedness that could not be broken by distance or time.

Trey

My family has lived on the other side of the state line, in South Carolina, for as long as we can trace. People rarely leave my hometown. In Gray Court, cows graze alongside single-lane roads; neighbors grow close, even overfamiliar.

When I was growing up, my parents asked me to do what few of our relatives had ever done — to leave. I received the same message that moved many Black Americans in the early 20th century: opportunity will not be found in the South; instead, seek freedom in a bustling city above the Mason-Dixon line. This belief fueled one of the largest population migrations in U.S. history.

Beginning in 1910, Black men, women, and children stuffed suitcases with their precious belongings and boarded trains to elsewhere. They wanted a chance at jobs away from the agricultural sharecropping system and the hot summers, to escape arbitrary and lethal violence, so they carved out passageways from Mississippi to Chicago, Louisiana to California, Alabama to Detroit, and the Carolinas to Washington D.C. and New York City. At least 6 million Black people walked, drove, and rode this path until 1970. Some of us still try to follow it.

When it was time for me to leave South Carolina for college, I followed my family’s instructions…sort of. I moved to the next state over, to Duke University in North Carolina. It seemed far enough away to be daring, but close enough to feel like home.

Early in my time, I encountered the racism that people expect may be commonplace in the Carolinas, racism that I thought I might escape in this supposedly liberal melting pot — much like the Black people who migrated in the 20th century and found racism in the urban north. the place they thought would provide refuge. In October of my first year, someone defaced a “Black Lives Matter” poster, scribbling out the word Black and writing “White” and “no niggers” with messy black ink. They left the bright yellow poster hanging on a public bulletin board as a warning.

The year before I came to campus, an international student hung a noose from a campus tree. This student claimed they did not know the meaning of the fibrous rope. The university president at the time responded with “a dream of a colorblind” nation, a fantasy that conceals our history and ignores our humanity. Malcolm X’s warning began to seep into my skin: “As long as you are South of the Canadian border, you are South.”

Growing up in the South toughened my skin against moments like these. I felt frustration, but no surprise. Although the majority of Duke’s students are not from the American South, anti-Black antagonism existed there, too. A melting pot of unsavory flavors, people brought unique iterations of racism to Durham from across the world.

Following these events, protest erupted. This was the post-Michael Brown era, where student activists across the country were actively challenging their universities to address systemic racism. I attended a town hall in 2016, during a celebration of Duke’s first Black students, organized by a group of Black students who stood on an auditorium stage fifty years on in front of hundreds of their peers, holding the university’s most powerful administrators to account. I found one person’s bravery and composure particularly striking — Bryce Cracknell. I didn’t know at the time that we would work on several activism campaigns together, from renaming buildings named after white supremacists to calling for better policies for campus workers. I also didn’t know he’d end up becoming one of my best friends.

Bryce

Trey and I met during the peak of the Black Lives Matter movement when hate speech and harassment were frequent happenings on campus. Our friendship blossomed over a common desire and drive for justice. We found belonging in a shared struggle, and soon learned that our demands of Duke were not new.

Duke had admitted its first five Black students around 50 years earlier, in 1963. The “First Five,” eager to pursue higher education, encountered an institution bound up in the same racial apartheid surrounding the campus walls. In 1968, the Black Student Alliance organized a silent vigil in response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. They also organized a march to the university president’s house demanding that he resign from a segregated country club, increase the number of Black faculty, and pay higher wages to Duke workers, most of whom were Black Durham residents. The following year, the students occupied the Allen Building to escalate pressure. They were met with local police, tear gas, and threats of expulsion.

Fifty years later, a weekend to celebrate these first Black students looked more like an attempt to whitewash history as many of their demands remained unfulfilled. Trey and I, along with a broad coalition of student activists, picked up the baton. We sought to tell the true stories of this university and to dream of a colorful and just nation. We protested, petitioned, taught, and struggled for each of our four years on campus. And we saw big wins.

We pressured Duke leaders to finally recognize the legacy of Julian Abele, the Black architect who designed Duke’s iconic Gothic chapel and West Campus at a time when he could not have attended the school himself. We pressured the university to rename a building that honored a white supremacist named Julian Carr. We campaigned for a policy change that would “ban the box,” allowing people with criminal legal system contact to apply for jobs. This particular victory mattered for people across the state because the university and its health system are the largest employers in the city of Durham and one of the largest in North Carolina.

College organizing taught me the power of storytelling and narrative, which pushed me to pivot from law school to instead chase my writing and filmmaking dreams in Los Angeles. I had the sense that I could build a home among the bright billboards, bustling highways, rolling mountains, and sunshine. However, I also felt a tug at my spirit that something was missing, a feeling I later came to know as dislocation. Trey and I were discussing how disbelonging greeted us in our new cities during a FaceTime call after he had moved to New York City.

Trey

Bryce told me he’d often meet people in various settings who asked where he was from and responded to “North Carolina” with a wide-eyed look of shock and judgment. “Good thing you escaped!” or “I could never live there; it’s so backward.” I encountered the same reactions in Brooklyn. “It’s a good thing you don’t have much of an accent,” or “I bet you’re glad to be out of there.”

These people, mostly well-meaning, believed the American story that the South should be written off. It pained me more to know that it was an idea I once held myself. It’s a convenient story — if America’s worst sins are held by one region, one people, then the rest of us don’t have to feel as culpable.

But these friends don’t know that so much of what they love about me, about Bryce, and about this country comes from the South. A place that has exported political, social, and cultural treasures that we all take for granted. Indeed, Black Southerners and their migration reshaped the demographics of big cities across the US. Their presence changed local politics and culture.

Bryce

Trey and I share a continued connection to North Carolina through an activist, lawyer, and spiritual leader who changed political life in the United States through our service as board members of the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice. Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray was the architect of some of the country’s most important civil rights cases, like Brown v. Board of Education, and was cited by Ruth Bader Ginsburg in a Supreme Court Decision barring discrimination on the basis of sex. In 2016, Murray’s childhood home on Carroll Street in Durham’s West End was declared a National Historic Landmark. Murray wrote that growing up in North Carolina shaped their life path and political analysis. They experienced life at the margins of society, and yet, they were surrounded by models of possibility in Durham’s Black community. Pauli eventually left Durham, blazing new paths in the law, religion, and social understandings of gender and queerness. North Carolina remained an anchor for their later exploration and discovery. Pauli Murray models the idea that home never leaves.

Because of this persistent callback to the idea of home, Black Americans are born appreciating the power of a diaspora. Kidnapped from our ancestral lands, we know what it means to build a new home while holding on to the whispers, scents, and rhythms of home before. Queer people, too, know what it means to choose a family and place of safety. Indigenous people and immigrants also know this story. In many ways, these are the communities that have been kept at the bottom of the caste system in the American South.

In 1894, the North Carolina legislature was ruled by a majority of former Confederates who objected to the progress Black Americans had made since the abolition of slavery in 1865. To break the stronghold of the then-Democratic party, poor white populists united with Black leaders to win power in the state. They recognized that together, they could make progress on economic and racial justice issues. During the November 1894 election, this “Fusion” coalition won statewide power. They implemented reforms that included increasing funding for public schools and the expansion of voting rights

To break this powerful multiracial coalition, the former Confederates ran a campaign of white supremacy ahead of the 1898 election. On Election Day in Wilmington, the white supremacist party attempted insurrection. An armed militia patrolled town, intimidating Black voters, threatening poll workers, and stuffing ballot boxes with illegitimate votes. After Election Day, these men gathered outside city hall and declared that they would never be ruled by Black people. The leaders incited a mob of over 2,000 white people, which roamed the beachside streets, lynching anywhere from 30 to 100 Black men, women, and children. The insurrectionists then used force to overthrow the duly elected local leaders, executing the first and only successful coup in U.S. history.

Trey

The statewide Fusion coalition began to fall apart after this massacre. But today, we remember the Fusionists for the years that they governed, standing for a moment in the sun. These leaders achieved what many people in this country have been attempting to replicate since. They united as Black and poor white people to break the stronghold of the former Confederates. For a brief moment, they bound together, building a North Carolina where all could be free.

Although Bryce and I are temporarily building lives outside North Carolina, this place remains with us. I research and advocate to protect voting rights and democracy in the U.S. Bryce writes, directs, and publishes stories that bring those who live at the margins to the center.

Our work is shaped by this state. We can never escape the Cookout milkshakes, college basketball fever, and small creek fishing or Bo-Berry biscuits, waking up early to chase sunrises in the Blue Ridge mountains, and walking along the Pamlico shorelines and the Wilmington beaches. We don’t forget the Fusionist movement for multiracial democracy. Moral Mondays. Purple politics. The possibility of a Reconstructed South.

Like America, this place is complicated and full of contradictions. It is a place that breaks our hearts yet holds them together.

All of us who have ever called North Carolina home are heirs to a powerful inheritance. Whether we stay there or migrate elsewhere, the new North Carolina and the new South are begging us to bring them into being. Let’s say yes. For ourselves, for our loved ones in the region, for seven generations to come. What happens in North Carolina might even ripple out and make this country anew.

This article first appeared in the Carolina Daze Essay Series. Find more articles here.

The CAROLINADAZE Essay Series is a project of Common Cause North Carolina in partnership with Facing South. To learn more and stay in touch, please visit carolinadaze.com and sign up for Common Cause NC's newsletter. Common Cause NC is a nonpartisan grassroots organization dedicated to upholding the core values of American democracy. Learn more at www.commoncause.org/north-

Tags

Bryce Cracknell

Bryce Cracknell is a writer, filmmaker, and publisher who seeks to elevate narratives, histories, and experiences that are often overlooked, cast aside, or forgotten. He is a writer on the CBS series FBI: Most Wanted, the Founder and Editor in Chief of the Anthem award winning environmental justice publication, The Margin, and is in post-production on his first feature documentary film on climate justice. Bryce is a proud North Carolinian currently based in Los Angeles.

Trey Walk

Trey Walk is an organizer, strategist, and writer committed to love, Black liberation, and the freedom of all who live at the margins of society. He has worked with organizations across the country on community organizing, providing direct client services, and winning policy change. Trey is currently based in Brooklyn and he continues to call the Carolinas home.