'Committed to our neighbors, whoever they may be'

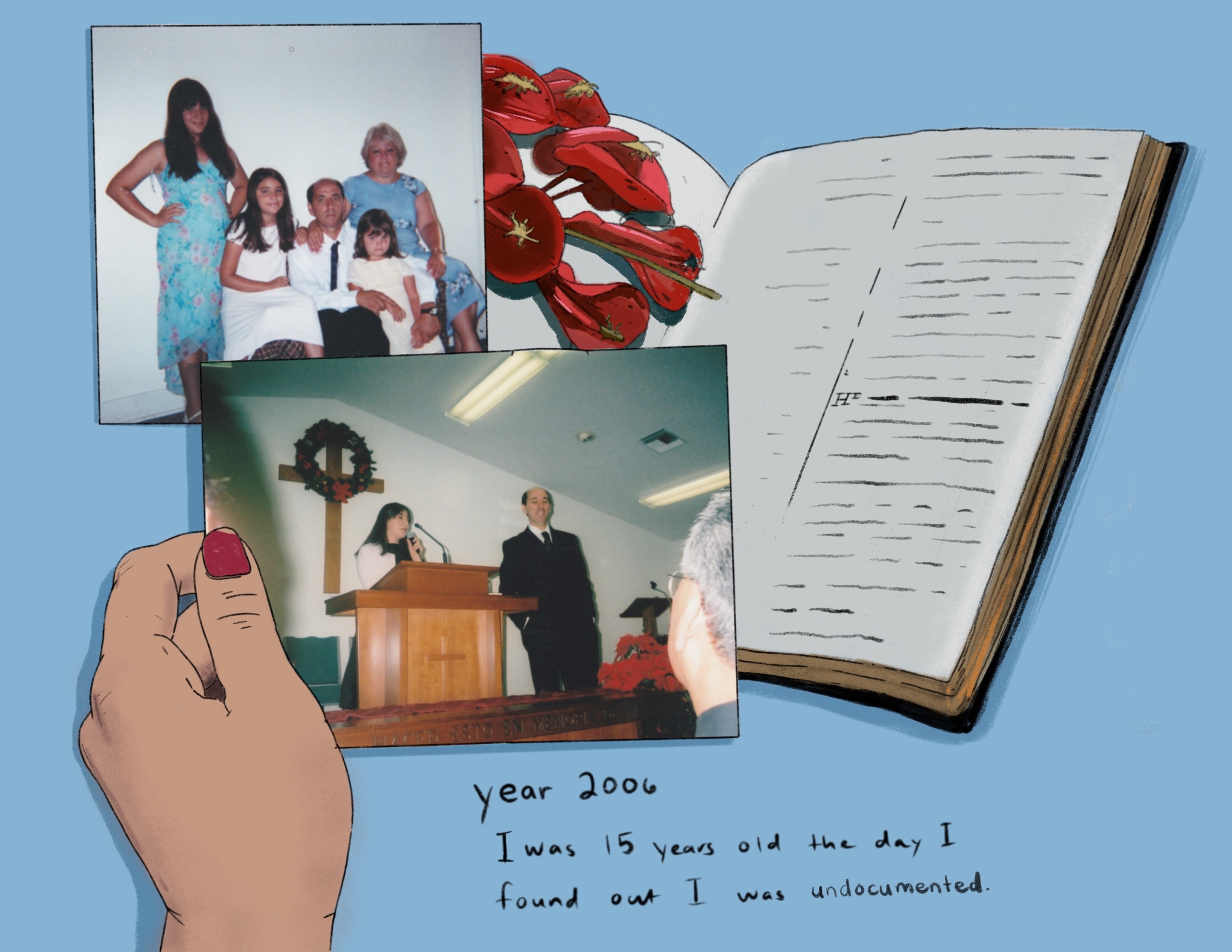

Archival family images are courtesy of the Sostaita family. (Illustration: Wutang McDougal)

This essay is the first in our CAROLINADAZE series, a joint project with Common Cause North Carolina featuring the voices of young North Carolinians and their visions for a better future for NC and the South.

This essay is the first in our CAROLINADAZE series, a joint project with Common Cause North Carolina featuring the voices of young North Carolinians and their visions for a better future for NC and the South.

I was 15 years old the day I found out I was undocumented. My parents sat me down at the cafe inside a local Barnes and Noble and explained we had overstayed our tourist visas, meaning I could not apply for a driver’s license. I would be ineligible for financial aid to attend college, and our entire family was at risk of deportation. As my parents spoke, I stared up at a mural depicting a salon of my favorite authors — Zora Neale Hurston, Emily Dickinson, Jorge Luis Borges. I recalled Hurston’s protagonist in “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” Janie, whose hopes and dreams had ended over and over again — just like mine in that moment. I remembered how Janie said that “God tore down the old world every evening and built a new one by sun-up.”

It was 2006. That same year my dad opened Iglesia Cristiana Sin Fronteras, or Without Borders Christian Church, in the suburbs of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. For the first few years, we met in an elementary school gymnasium — our presence in the space only temporary, our ministry improvisational.

My dad imagined the church as a space for fellow migrant families to gather without fear and to nurture a community rooted in struggle. I was in high school and terrified that being undocumented meant I no longer had a future. But, my dad’s sermons and the activism of our church taught me that futures are always being made in the present. And that being undocumented was not necessarily a barrier I had to overcome, but a way of seeing the world differently and a reason to fight for a more just one.

My family migrated from Buenos Aires, Argentina to Rural Hall, North Carolina in 1998 — a time when immigration enforcement was being radically expanded by the Clinton administration, but before the Bush administration created Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which further expanded enforcement operations in the wake of September 11, 2001.

In 2006, following the rising criminalization of migration, undocumented people mobilized and launched the Primavera de Migrantes, or Spring of Immigrants. They demanded immigration reform like never before in U.S. history: millions of people took part in demonstrations at more than 200 locations across the country. In this moment, I witnessed the importance of churches as places of organizing and community building. North Carolina organized a total of 21 protests during that spring, more than any other state besides Texas and California. Churches, including ours, were crucial in those mobilizations. I was a teen and it made me realize that the God I worshiped was one that awakened people, that energized and inspired them.

When I asked my dad to describe his theological vision, he pointed me to the Sacerdotes Para el Tercer Mundo, or Priests for the Third World. This was a Catholic movement in Argentina that coincided with the emergence of liberation theology and expressed a longing for a socialism rooted in the global South — one not predetermined by European thinkers, but rather reflective of the needs of people in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. My dad met some of these priests as a child in the 1970s, before he converted to evangelical Christianity, and they taught him that militancy is inseparable from religion. To be a Christian means struggling for the world you want to see, one liberated from the domination of global capitalism.

My dad’s response to my question points to the ways Christianity in the U.S. South is connected to religious practices in the hemispheric South — how collaboration and solidarity emerge across borders. According to him, “our struggles are taking place in different contexts, different scenarios, different time periods [but] the oppressor is the same and the marginalized or oppressed are the same.” By this, he does not mean that oppressors share a common racial, ethnic, or even national identity; rather, across borders, they are motivated by the interests of capital, extorting and controlling governments that, in turn, extort and control el pueblo, or “the people.”

My dad tells me that his congregation’s political awakening happened in 2010, when a church member approached him with an emergency. The man had received ten traffic tickets in the span of a month; the fear of collecting another one consumed him. His driver’s license had expired months before and, lacking legal status, he could neither renew it nor his car’s license plate sticker. He was a target for the police. They knew the exact vehicle he drove and patrolled the neighborhood where he lived (a predominantly Latinx apartment complex). The man had no way around their checkpoints. My dad recruited help from lawyers, nonprofits, and community organizers. He knew there were likely many others facing similar violences, and that it was not enough to only support members of his church. Since then, Iglesia Cristiana Sin Fronteras has become among the largest activist Latinx congregations in North Carolina.

There is a long and rich history of church-based organizing in the South, and particularly in North Carolina. From the Civil Rights Movement to Moral Mondays — a tradition of civil disobedience led by Reverend William Barber in opposition to austerity measures and racist voting restrictions proposed by the state legislature — North Carolina's churches challenge ideas of religion as an impediment or obstacle to progressive social change.

More recently, during the Trump administration, North Carolina churches offered sanctuary to migrants facing deportation orders: among them, Juana Luz Tobar Ortega, José Chicas, Eliseo Jimenez, Minerva Cisneros Garcia, Rosa del Carmen Ortez-Cruz, and Samuel Oliver-Bruno, who died in 2021 after being deported to Mexico. North Carolina was among the states with the largest population of people living in sanctuary, practicing what scholar Saidiya Hartman calls “care as the antidote to violence.”

These congregations offer different stories to the ones we are used to hearing about evangelicals, especially those in the U.S. South; stories that sensationalize evangelicals as uniformly xenophobic, homophobic, and backwards in their political orientations. Especially during this election cycle, national media outlets are obsessed with the figure of the Latino evangelical, claiming that this demographic is expressing a “growing support for Christian nationalism” and that they are “re-energizing the Republican Party.” This broad-brush analysis ignores the nuance in the Latinx and/or migrant experience, falsely placing all evangelicism squarely in line with the white right-wing political bloc.

But this fascination with Latinx communities who seemingly betray their own interests or whose religious commitments have more in common with right-wingers — who, ironically, are the same ones waving “Mass Deportations Now” signs at Republican rallies — ignores the creative religious organizing happening in places like Winston-Salem. Here, congregations like Iglesia Cristiana Sin Fronteras have organized to end the county contracts with ICE, to demand safer housing conditions from negligent landlords, and to meet the needs of Latinx community members in the face of state neglect, for example, in the wake of a fertilizer plant fire.

This kind of coverage is largely missing in local media and beyond, even from well-intentioned journalists who center the work of North American Christians “welcoming” the stranger and supporting recently-arrived migrants as they assimilate to this country. Much rarer is it to contend with the activism of migrants themselves, to take undocumented people as political agents, to take seriously their contributions to social movements.

In recent years, Iglesia Cristiana Sin Fronteras has focused on meeting the material needs of Winston Salem’s growing and rapidly diversifying migrant population. More and more people are arriving from countries like Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador. Unlike migrant communities with deeper roots in the South, these families are not reuniting with family and friends who have already settled in the US. They lack social networks, driver’s licenses and reliable means of transportation, access to healthcare, and support from bilingual staff in the school system.

This past spring, in collaboration with the North Carolina Congress of Latino Organizations, the church invited the Winston-Salem mayor, sheriff, county commissioner, and CEOs of Partners and United Health, two local health management companies, to a public forum. Approximately 500 Latinx community members attended, their presence a signal of their political power. The priorities for the meeting — access to mental health services, the construction of a new community health clinic, an expansion of the deadline to apply for U visas — emerged from a months-long listening session campaign where migrant community members determined their shared priorities.

At the forum, Reverend Angelica Regalado described how, for years, she and fellow religious leaders have heard the same complaints from their congregants: that they cannot access healthcare due to a lack of public transportation, that they fear driving without a driver’s license and sharing their personal data with hospitals, that they lack health insurance and cannot afford their medical bills. Religious leaders are also concerned about the city’s mismanagement of U visa applications — intended for people who suffered mental or physical abuse or were subject to a crime and who are willing to help law enforcement or government officials investigate or prosecute criminal activity. According to Regalado, applicants wait for months on end to hear word from the police district about their applications. Many never even receive rejections; their applications are simply ignored, lost, or discarded.

When my dad took the stage, he described the mental health concerns facing his congregation, concerns that are exacerbated (and often even caused) by undocumented status. Bilingual and bicultural therapists in the area are completely overwhelmed, and their wait lists are seemingly unending. He asked city officials to fund a mental health promotores de salud program in Forsyth County—a model that trains trusted members of communities to serve as health workers and to facilitate collaboration with the healthcare system.

After making demands on the officials sitting on the stage, he addressed the community gathered on the pews. “Hoy estamos acá,” he suggested, “porque nos escuchamos, nos podemos mirar. Nos sentimos los unos a los otros. Y sentimos el compromiso de una comunidad solidaria, comprometida con el bienestar del prójimo, sea quien sea.”* My dad and his church members are organized in struggle because — in his words — they can hear, see, and feel each other. Because there is something like a bodily communion taking place through their listening sessions and through organizing that awakens the body and its senses. Because they are attuned to their neighbor’s material, bodily, and everyday needs.

The community won all of their asks that day. But my dad tells me they will keep organizing to make sure city officials keep their promises.

In the meantime, they will continue being the kind of space I needed growing up undocumented, a space where I could speak openly and vulnerably about my status and where the Bible offered a message of solidarity and resistance. Iglesia Cristiana Sin Fronteras’ theology is already made clear in the church’s name — without borders or without frontiers. Like Macarena Gómez-Barris, they teach us that “the dream of another world is not merely a future-oriented utopia but it is already in motion, teeming with the alternatives we desire.”

The future in motion at my dad’s church is one without borders, where people are free to migrate and also to return home. Where undocumented status does not limit possibilities for making and sustaining life. Where — to return to Hurston — God tears down old worlds every night and rebuilds them in the morning. Change and transformation are celebrated, nurtured, and honored in such utopias. No state or political power can limit people’s potentials, dreams, or strategies for flight and escape.

* “Today we are here, because we can hear and see each other. We can feel each other. And we feel a commitment to a community rooted in solidarity, committed to the wellbeing of our neighbors, whoever they may be.”

Image: Archival family images are courtesy of the Sostaita family. Illustration by Wutang McDougal.

This article first appeared in the Carolina Daze Essay Series. Find more articles here.

The CAROLINADAZE Essay Series is a project of Common Cause North Carolina in partnership with Facing South. To learn more and stay in touch, please visit carolinadaze.com and sign up for Common Cause NC's newsletter. Common Cause NC is a nonpartisan grassroots organization dedicated to upholding the core values of American democracy. Learn more at www.commoncause.org/north-

Tags

Barbara Sostaita

Barbara Sostaita is a formerly undocumented writer and scholar of religion and global migration. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Latin American and Latino/a Studies at the University of Illinois Chicago. Her first book, Sanctuary Everywhere: The Fugitive Sacred in the Sonoran Desert, was published in 2024 by Duke University Press. Barbara's writing appears in The Nation, Bitch, Teen Vogue, and Remezcla among others.